Max Zippin pays tribute to the sacrifices and ingenuity of Siberia’s Red guerillas fighting behind White lines and against imperialist intervention in Russia’s vast east.

‘The Power Behind the Red Gun’ by Max M. Zippin from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 2 No. 8. February 1, 1920.

THE astonishing onward sweep of the Red Army of the Russian workers and peasants in Siberia, and in the “domain” of Denikin, has naturally startled the world and compelled the Allied governments to sit up and take notice. A friend of mine with whom I was traveling over the Siberian railroads, in the days of Kerensky, and in a “courier” train at that, called my intention to the fact that the Red Army was actually making much better time now than we were, and certainly had not as many stops, nor such long ones, as we were making. Indeed, it is not at all an offensive movement that the Red Armies are performing now in Siberia. It is a walkover.

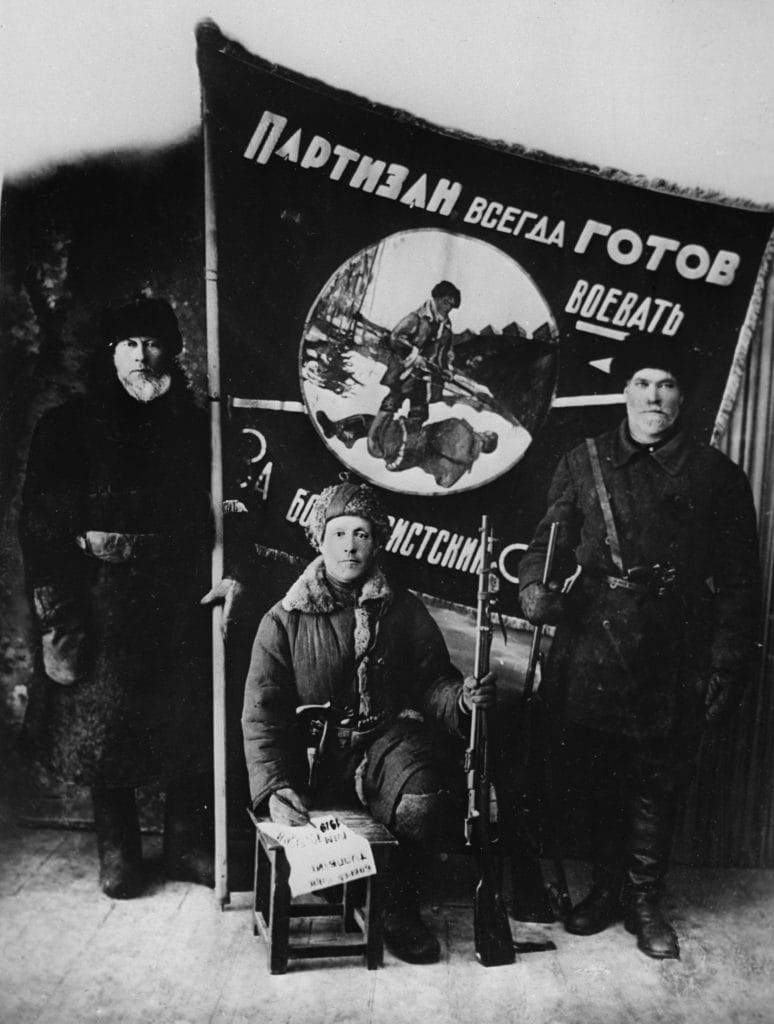

Of course, it is because it is a red army that the Red Army is enabled to accomplish all these wonders. Another army, not so animated with one great idea, and not so heartened by the conviction that the Russian proletariat will eventually come out the victor over all the forces of the exploiters and speculators, could never thus succeed, and never has thus succeeded, in the history of mankind. But there is in Siberia another power that should have an equal share in the laurels of the Red Army. I refer to the little “red” so-called “guerilla” detachments, here, there, and everywhere in Siberia, all along the wide steppes, the thick forests, the long roads, the cities, big and small, the villages and hamlets of Siberia. I refer to the Siberian Bolsheviki, who never let their guns fall from their hands, and who have been constantly boring from within that decaying body, politic and civil, of the Allied darling, Koldia, And I am convinced that were it not for the courageous and heroic Comrades in the rear of the Kolchakists, and their martyrdom, the Russian Red forces would have hardly had that holiday jaunt over Siberia (and this is equally true in the case of Denikin and whatever their other names may be).

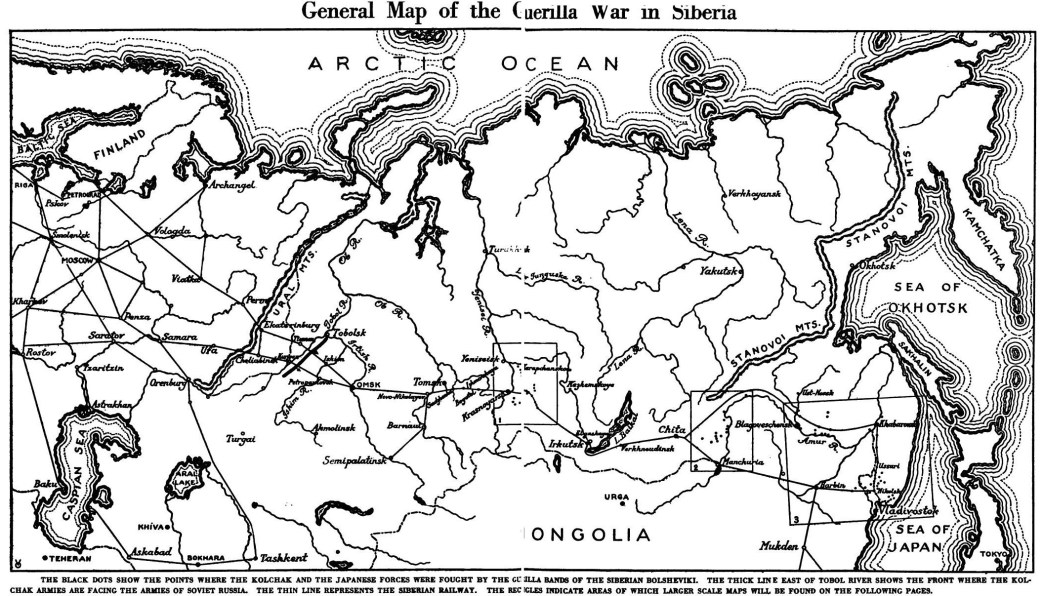

In Soviet Russia attention was called to this fact several times. The map of the guerilla warfare was published by Soviet Russia in its issue of October 18, and the numerous articles on this subject, have given at least a partial conception of what the small but powerful red detachments have achieved in Siberia. But since this was all compiled from Siberian newspapers, as it could not otherwise be, and since most of that was achieved in Siberia by these little brave forces was suppressed by Kolchak’s and the Allied censors, we hardly know anything of what was really done there. Only the final victory over the black forces, that is being achieved now, will make it possible for us to delve into all the facts and know the full story. Only when Russia will free herself from her enemies, interior and exterior, and be in a mood to write the profuse history of her Revolution, will we have a real insight into the great work done by the “local reds,” as they are frequently referred to by the Allied press, a work as magnificent as the great Revolution itself. And only then will we know how great were the sacrifices that these “local reds” have brought, and how many of them have perished in this colossal struggle for the happiness of the Russian masses. The liberal world knows fairly well today what Kolchak has done to his opponents, even of the lukewarm type of socialists, and it requires no stretch of imagination to understand how the Bolsheviki of Siberia have fared when they fell into the hands of the Allied fighter for “democracy” who now fights no more.

And I honestly believe that we should be paying only a small part of our debt to these brave and heroic “local reds” if we were to state that it was they that have made the victory of the Red Army so seemingly easy, and its task so apparently light. Because when the Red Army entered a city, or a village in Siberia, or else took possession of a part of the railroad, it found the ground prepared and the road ready for its coming. It was always met by a population not only friendly, but enthusiastic and impatiently waiting for it. And some one had to prepare the condition for the Red Army. Someone had to keep the great red fires always burning in the midst of that black Allied-Kolchak atmosphere. Someone had to uphold the great idea and to keep alive the great hope in those terrible surroundings created by the Kolchak blacks and Allied whites. And the “local reds” did it.

The following is again only an additional and partial enumeration of the activity of the Bolsheviki, of those true martyrs, living and working under the constant fear of death and torture at the hands of Kolchak in Siberia. I have it from information found in Siberian and Japanese newspapers, and some of the documents that have even the official stamp of the Japanese High Commander, that is, that were published by the man who was entrusted by the Big Four, or Three, or Two, or One, to ward off, as the saying goes, the red terror from Japanese and other democracies. I am merely mentioning this fact so that the gentlemen who are nosing about for sensational stuff and romantic stories for the friendly newspapers may not be disturbed and may partake of their fat meals peacefully. There is nothing subterranean about the whole affair, and there is no “special red courier” involved in it. It came by the straight legitimate road, via the Chinese, and hence, the American post offices, and not in the soles of the boots of sailor-boys, who manage apparently to carry stores of goods as large and as various in assortment as that of our big department stores, and then only in one sole of one boot—or is it a shoe?

The following is a true translation of a proclamation by the “local reds” which had a very wide circulation all over Siberia and which, as was proved satisfactorily, came from one and the same quarter, which again proves quite conclusively that when some one said some time ago, that all the red detachments of Siberia were unattached and not connected with any central organization, he was simply mistaken:

“Comrades: The foreign bands, in collusion with our thickheads and hangmen, have throttled our October revolution here in Siberia, and have overthrown our people’s government.

“The enemies of the working masses, the enemies of our revolution and the Soviet republic, the friends and the sons of the bourgeois elements in alliance with the soft-bodied traitors, the Mensheviki and the Socialists-Revolutionists, are robbing us of all the freedom and rights that we have won by our blood, and for which the Russian working class has striven for long generations. They are reviving the old order that the parasites, the manufacturers, the land-owners, and the czarist officers may again live in luxury. They are returning to the village exploiters the land that they robbed from the peasant, and to the officers their golden braid and high pay.

“Our enemies are destroying our revolutionary order, our acquired rights, together with the land riches that the workers, peasants, and Cossacks have created by much labor and endurance. Let us, therefore, all of us, revolt as one man against them and let our battle cry be: Down with the exploiters.”

A short, concise proclamation. Nothing is told here of the future plans, as is the case with the proclamation of the Socialists-Revolutionists calling upon the masses to revolt against Kolchak, that was published in Soviet Russia 3 weeks ago. It is not necessary. The Russian workers and the poor Russian peasants know well from experience what the Soviet form of government has done for them; they know equally well that it is their government, and they surely know what to expect of it when it is again restored to power.

The “local reds” of Siberia need money and food to hold together their organization and their fronts. How do they do it?

“We are torn away from our center, and we are compelled to shift for ourselves for a while,” reads one order of the Revolutionary Committee, “and until our Comrades will come to our rescue we shall have to acquire food and finances by means of our own.

And then comes the plan, which is as simple as you can make it, and, judging by their successes, it works remarkably well. The plan in a few words is this: The financial needs of the revolts are covered by moneys seized from Kolchak government institutions, or expropriated from rich speculators, or by compulsory contributions from the same, which amounts to about the same thing. In every town or village where there is a revolt in progress, or in contemplation, there is always a revolutionary staff that takes care of this part of the program. It will be interesting to add that there is a uniform decision by the “local reds” that the revolutionary staffs under no circumstances shall expropriate the poor or even the middle peasants. There is also a strict order to each and every red soldier to pay in full the market price for all the food and forage they are compelled sometimes to take from the middle peasants.

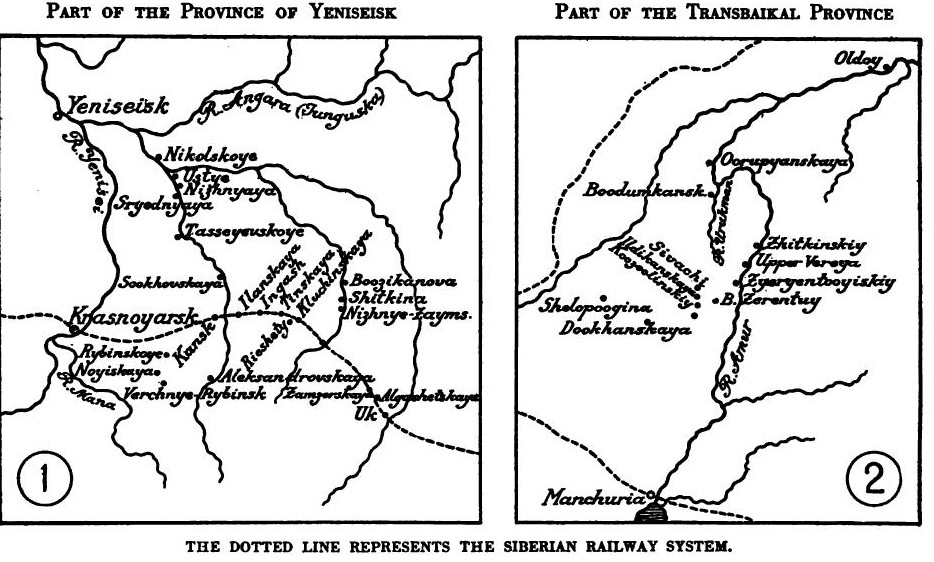

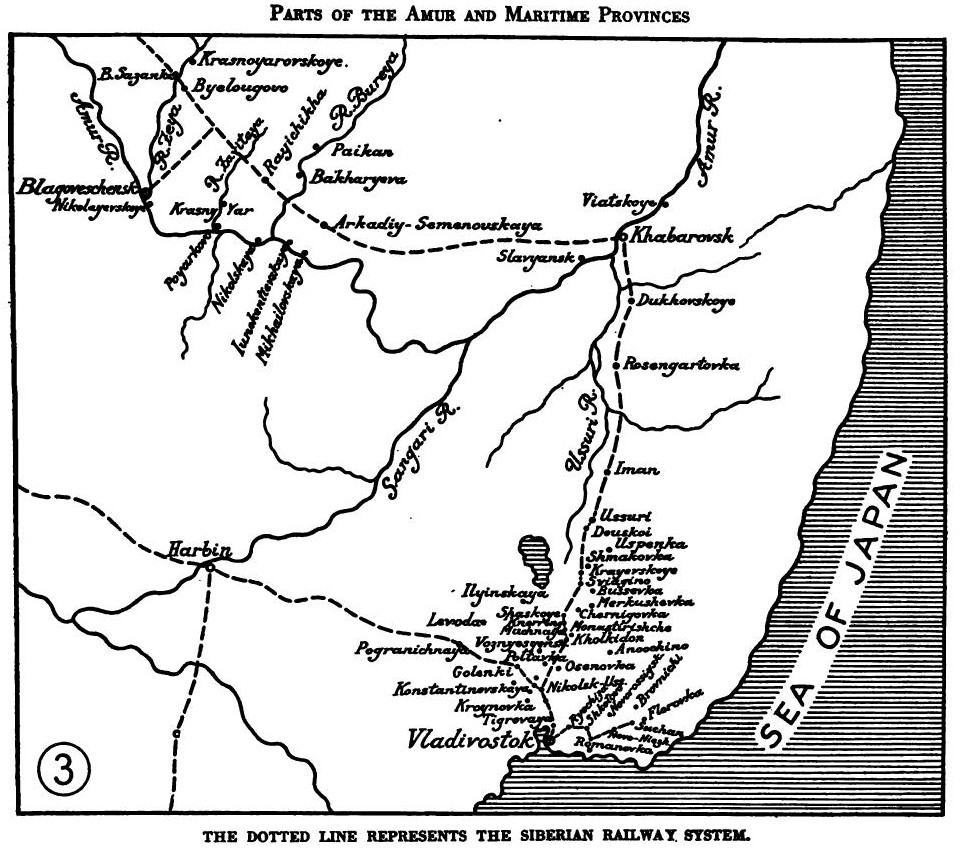

Ammunition is acquired by a still simpler method, namely, by getting hold of the Allied ammunition sent to Kolchak and the others. The fact that all these “bands” are thoroughly armed is conclusive, evidence that this method is successful; they have no other sources there. There is even an order on hand showing how all the ammunition that the “reds” have appropriated from the Allies was delivered to the little partisan detachments spread over the Amur and Transbaikal region. Again, by the simplest method imaginable. “For the purpose of delivering the ammunition” the order tells, “there has just been organized a big transport, consisting of the wagons and horses recently confiscated from Ataman Semionov.” Perhaps that is the reason why the Chief Commander of the American forces in Siberia refused to give to Semionov a portion of the American rifles, sent to Kolchak, and there was nearly a break in the diplomatic relations of the American Government and His Excellency, the Prince of Mongolia, the Chief of the Robber Bands of the Buriats, etc., etc., “General” Semionov. But then, sending these rifles further West, that they might reach their destination, was by no means giving full comfort to Kolchak. The “local reds” had spread all over the Siberian road, and there was at that time a pretty powerful “band” near Novo-Nikolayevsk, and, sure enough, they got some of it. All in all, it seems to me quite erroneous on the part of foreigners to “kick” against the Allied governments for their helping only one side in the Russian civil war against the other, while continuously professing not to interfere in Russian internal affairs. The bulk of the war materials sent to the “saviours” does reach the red armies, the red “bands,” and the “local reds,” whether the Allies will it so or not, and we should be rather thankful to them for the part they are playing.

Contrary to the popular belief, or rather to the Allied press, the “local red” armies of Siberia are organized in the most efficient manner, and most careful discretion is displayed in their mobilization. One must bring the most reliable proof that he is worthy of joining these little red forces. According to an order on hand, in the revolutionary armies of the Bolsheviki in Siberia, only volunteers are admitted, and only such as have proper recommendations from at least three persons well known to members of the groups as proved and tried supporters of the Soviet Republic. And this holds good for all the “local red” detachments all over Siberia. In the little red armies the most stringent revolutionary discipline is maintained, only the noncommissioned officers being elected by the members of the detachments, while all the other higher officers are appointed by the revolutionary staffs and are subordinate to these revolutionary staffs. The order is uniform, and while the whereabouts of the High Command of all these detachments is unknown, it nevertheless exists and displays an undisputed authority over the detachments, is in constant communication with the local revolutionary staffs, scattered over something like five hundred fronts, over a distance of some eight thousand miles.

They have also a number of secret organizations in the Allied-Kolchak armies, whose mission is to demoralize these armies, again under the leadership of a powerful if, for a while, unseen Committee.

There is sufficient proof to show that these secret organizations have performed their task to perfection. But one can rest his case by merely quoting the Associated Press correspondent, who is not supposed to tell the whole truth as long as he can help it. The quotation is from a despatch from Taiga, at one time Kolchak’s headquarters, and it reads:

“According to well informed circles the Siberian armies were demoralized under Bolshevist propaganda, and, due to the long retreat, the men did not desire to fight. Their officers did not dare give battle under the circumstances. Because of desertions, the armies have dwindled to mere skeletons. Several units have been killed and some of the officers have gone over to the Bolsheviki.”

In the Siberian cities, the Bolshevik propaganda never ceased, and the tortures and the revolting atrocities of Kolchak never hindered them. All the workers were openly with the “reds,” and whenever there appeared a publication of the workers not merely for the workers, it was always Bolshevik. Of course Kolchak quickly suppressed these workers’ publications, but they managed to reappear again and again, and most of the time under the same names, if under different editors. In Vladivostok, for instance, there appears and reappears a publication of the organized workers under the name Truzhenik, which is thoroughly Bolshevik. Another paper of the same policy appears and reappears in the Amur region under the name Rabochiy, and so forth. Great numbers of the town workers and of the railroad workers readily join the forces of Kolchak, in order to desert afterwards with the ammunition and equipment that the Allies have so obligingly supplied them with, even if by an awkward and bloody road. Rumors of the victories of the red armies spread like wildfire among the town workers, and are hailed with joy, and all the assurances of the Kolchak commanders to the contrary help but little. And every victory of the red armies is a signal for the “local reds” to come out into the open and prepare for the further victorious advance of the Red Armies.

One would suppose that in the villages the Socialists-Revolutionists, with their mission of democracy, and the great words of the Constituent Assembly on their lips, have more luck. Not so. In the villages as in the cities it is the “local reds” that dominate and whose propaganda is supreme.

The Russkaya Ryetch (Novo-Nikolayevsk) tells of a whole series of villages where the peasants refuse to pay taxes to the “government” as well as to the Zemstvos. In the village of Novotroitsky, county of Bakinsk, the peasants held a meeting and and passed the following shortest resolution on record: “Taxes we will not pay and you can’t do anything to us.” The collector sent out a hurry call for a punitive expedition, but no punitive expedition dared approach this village. The above Kolchak organ takes rather needless pains to prove that it is all the work of the horrible Bolsheviki. In the villages of Isakovskaya, Zhuravlevskaya, Moskovskaya, Tulskaya, the paper adds, the Bolsheviki have actually all the peasants with them, and have organized them for resistance.

One county Zemstvo tells officially that the peasants of Agafonikh and of Vierkh-Agaf have refused to pay their taxes, being under the influence of the Bolsheviki. Furthermore, the mobilized (by Kolchak) in these villages are not only not handed out, but actually defended by the population.

In Svobodnaya Sibir a correspondent enumerates a number of official communications on hand, show the feeling in the villages.

One reads: “The president of one of the largest villages near Irkutsk, in answer to the question of why the collection of taxes is so slow, writes that the population flatly refuses to pay them, claiming that this government of Kolchak is only temporary, and declaring that they will pay taxes only to the Soviet governments. And he adds that there is no means of collecting, since even punitive expeditions have availed nothing.”

One president of a Kirghiz village writes: “How can you expect any payments from the population? There was, first, the Provisional Government, then came the Soviet Government, then came the Siberian, then the all-Russian, then the Directorate, then the Dictatorship. The peasants plainly state that they want to wait until there will be a stable government.” He too, confesses that it is all the result of the Bolshevist propaganda. The correspondent enumerates a number of villages where the peasants have done away with the tax collectors, quite openly, “that the enemies of the people should hear and learn.”

There is a confession of one of the Zemstvo workers that went to the villages to carry to them the great tidings of the organization of the Siberian Committee that was to overthrow Kolchak and the Bolsheviki. It was in the Amur region where he intended to work and his experiences are related in the “Rabotnik” of Blagovieshchensk, one of those little struggling Bolshevist organs that appear and disappear again, under the nose of the watchful Allied commanders and their allies, the Semionovs and the Kalmykovs.

“Almost all of the young men in the villages have left for the Bolshevist fronts, and there remain only the old folks and the children. And it is remarkable how even the old pious peasants are supporting the Soviets. They are not at all convinced that their sons have acted right in leaving for the numerous red fronts. They are not at all sure that this action is in accordance with their religion, and their old beliefs. But then it is their own sons, their own blood, and right or wrong, they cannot help siding with them. But while their feeling towards the Bolsheviki is somewhat hazy, their hatred toward Kolchak is both open and outspoken, and their hostility towards the Zemstvos and all the other so-called democratic organizations is even more glaring. Often our workers were attacked bodily by the old villagers who blamed all the troubles on us. ‘Why don’t you let our sons alone? Why do you come to aggravate us in our pain? It is enough that we have two fighting sides, and there you come with a new one”–were interrogations and explanations that were hurled at our workers from all sides at the meetings.

“One of our workers was nearly torn to pieces because he had chosen to make an insulting remark about one of the leaders of one of the villages, one who had since gone to the red front. Grishka was his name, and the Zemstvo instructor tried to belittle him, telling the peasants that Grishka was after all only an illiterate. A wonderful cry of anger came from all sides. They have known Grishka since childhood and they can all vouch for his honesty. Besides, ‘if he was as unimportant as you say’, came from one of the audience, ‘how is it that the Americans, the Japanese, the English, the French, and all the world are after Grishka?’ One had to hear the outbursts of the peasants. They are actually proud that one of theirs has become so important a figure as to have the whole world of governments after him.’

Another one tells of his experiences in the Trans-Baikal region, another of the Japanese-Semionov “spheres of influence.” The villages are almost depopulated, the young men having gone to the fronts of the “local reds,” and the old folks and the children hiding in the woods or in the surrounding hills from the wrath of the Japanese and Cossack fighters for democracy. No cultivation is visible for hundreds of miles, and nothing but bare land is before the eyes. The little houses are closed tightly and only here and there, from the interior of some, a sigh comes that is quickly choked off. They have had many assaults by the punitive expeditions and they are in constant fear of such. There is no oil to be gotten and when night arrives a gruesome darkness enwraps the village. The schools have long passed out of existence. The libraries that were built once with so much love and hope, are like phantoms. Only once in a while the frightful monotony is broken by an outburst of a drunken cry or intoxicated laughter from one drunk with the poisonous Japanese liquor or Kolchak monopolized vodka.

The relater tried to organize the remaining few into a local of the Socialist Revolutionist party. He was nearly stoned. They wouldn’t hear of any other party but the Bolsheviki, or rather the Soviet party. They openly lay all the blame for their plight at the door of the Socialists-Revolutionists and the Zemstvos. Weren’t these parties once supporting Kolchak and the Allies? Not a kopeck would they give for the so-called democratic organizations. Surely nothing to the tax collectors. But the secret emissaries of the “local reds” that come in the nights are fed with the peasants’ last crumbs.

The following humorous incident happened in the village of Tabagatay, in Transbaikal. The villagers, for the most part old men, have sacked the big flour mill of Goldobin there and the stores were quickly despatched to the red fronts of the neighborhood. Previously the Bolsheviki had organized a full detachment in that village of the local young men. The leader was one officer, Smolin, by name, a stranger to the villagers, but a powerful and convincing speaker who quickly won the masses for the cause of the Soviets and was idolized by them. When the punitive expedition came, the leaders disappeared and the peasants left there have suddenly all became “dark people.” “We are a dark people,” they pleaded, “and we only do what we are ordered to. An officer came and told us to organize for the defence of the fatherland, and we did. He then told us to carry off the flour of the mill because the owner was against the fatherland, and because it was needed for the defenders of the fatherland, and we obeyed. We are only a dark people.”

And these are only fragments of the big story of what the “local reds” have done and are doing in Siberia to prepare the road to victory of the great red armies.

Of course, it must be conceded that the Kolchakists and their Allies have helped greatly these little red “guerilla” forces by the mere fact of their being so cruel and atrocious to the population. I presume President Wilson had just these atrocities of Kolchak and the Allies in Siberia in his mind when he said, in his message to the Jackson day diners at Washington: “The world has been made safe for democracy, but democracy has not been finally vindicated. All sorts of crimes are being committed in its name, all sorts of preposterous perversions of its doctrines and practices are being attempted.” The unspeakable Russian Monarchists and their friends, the foreign Imperialists, were undoubtedly powerful, if unwilling, confederates of the “local reds” in Siberia, and have greatly helped the latter to win the fullhearted trust and the unwavering support of the masses. But this does not diminish in the least their gigantic accomplishments. And while we express our wonder and admiration of the great Red Forces of the Russian workers and peasants, let us not forget the little red “guerilla” and the “local reds” detachments that have paved the victorious road for them.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v1v2-soviet-russia-Jan-June-1920.pdf