Emanuel Eisenberg on the ‘high’, ‘low’, proletarian and indigenous Mexican theater of the early 1930s.

‘The Theatre in Mexico’ by Emanuel Eisenberg from New Theatre. Vol. 2 No. 12. December, 1935.

The first glance at the contemporary theatre in Mexico is a confusing and distressing one–for, in a country that calls itself revolutionary, that smears up its public walls with the hammer and the sickle as lightly, say, as William Randolph Hearst babbles in his senile beard about Jeffersonian democracy, one looks in utter vain for the dimmest sign of a revolutionary or a workers’ or even a merely “social” theatre. But as soon as the extent of imperialist domination is realized, as soon as it is understood how thoroughly colonial and provincial a life is enforced here, each aspect of theatre expression becomes intensely significant and revealing.

(Mexico is technically, of course, semi-colonial, since it possesses its own government which is acknowledged by other powers. Throughout this article colonialism is referred to as a psychological condition of the people.)

The Spaniards, with their overwhelming religious machinery, started the conquest on a good large scale with a tremendous appropriation of lands, all in the name of the church. They proceeded to the usurpation of practically all the minor productions, such as bread, hats, shoes, furniture, alcohol, and the control of agricultural distribution. The French were glad to aid in industrial expansion by monopoly of the textile industry and ownership of all the larger clothing stores. The Germans arrived with all manner of machinery and dyes and inks and remained to see that the profits came in steadily. The Swedes had just about managed to install a telephone system when finally, and most magnificently, the Americans broke in. With unfailing piratical gusto they not only established a rival telephone system which became far more widespread than the Swedish but promptly set about the complete taking over of railways, highways, airways, mines, petroleum fields, water power, and exclusive control over the shipment of bananas and the sale of automobiles.

The effect of this fantastically absolute imperialist set-up, which naturally had the complete approval and collaboration of the corrupt government powers, is inevitably felt in all of the arts. The practitioners respond in two ways: either they yield completely to the intense foreign influence and turn out carbons of European chic, or they turn with juvenile violence to indigenous themes and emerge with stridently self-conscious and nationalistic folk lore. A small group of authentic revolutionaries is struggling to find true forms and create a sure understanding audience, but they have a gigantic problem in the face of an official demagogy which is without parallel and without precedent. The government, impaled on unignorable revolutionary traditions, hands out portraits of Lenin, talks of a not yet existent socialist education in the schools, writes in its official organ about the gradual dictatorship of the proletariat and firmly proceeds with the Six-Year Plan, a project of fascisization of all labor and education and culture. The public confusion is incalculable…

As if in perfect illustration, three kinds of modern theatre exist in Mexico: the carpa, or street tent-show for the lumpen-proletariat; the respectable commercial hideaway for the bourgeoisie, always an extremely small class in a colonial country; and the incredible foreign affectations and “preservations” of the government for xenophiles, esthetes, snobs, parvenus, tourists, classicists and archeologists.

The carpa is a curious institution for which America has no equivalent. Think of it as an uncertain composite of the old style minstrel show and vaudeville show and the contemporary burlesque show, with trimmings of political kidding in the form of easy couplets, and you have a fair idea of contents and intentions if not of style. But the style is, of course, what counts–and this is almost beyond communication, since it ranges (as with us) from utter mechanical boredom on a Monday night to rich electric contact on Saturdays, depending largely on the audience. Our actors, too, respond to good audiences, but here it is actually a matter of the public making its desires and preferences known. Often enough this takes the form of aimless hoodlumism, as when the boys howl for the girls to take another turn on the apron run-way so they can pinch their legs, or when some cry to see the bamba danced and others long for the jaiba. But it can also achieve such a perfect fusion of actor and audience as the Conde Boby, an uproarious act of ventriloquism which consists mostly of spontaneous attack by all spectators so disposed and fresh and juicy riposte by the extraordinarily agile dummy.

It is a rich and a heartening thing to see these audiences, for the greater part illiterate, consisting of such diverse elements as Indian women with their babies, market-vendors, mechanical and street workers in their overalls, young apprentices loose from their dreary shops, young shop-girls and office workers free from the stiffness of their daily grind, destroying the preposterous barrier of the stage line and making the carpa their own.

To the extent that these theatres are simple and inexpensive constructions which are dismantled about once a month and shifted from market place to workers’ district all over Mexico; that the admission is very low (30 centavos Mexican, 9c American) and laborers can enter in any costume whatever; that audience participation can actually condition the speed, gaiety and content of the show: to this extent the carpa belongs to the people and represents an instinct for proletarian theatre. To the extent, however, that most of the songs and skits and performers and flat painted curtains are discards, wash-downs or memories of the imported bourgeois zarzuela (revue) of the Spanish and French music hall of the late 19th century, the carpa’s essential attraction is for the harassed and beaten lumpen-proletariat (and, of course, to enchanted slummers from Uptown). As a known medium and with an habitual theatre-going public, this form has tremendous possibilities for development into a class-conscious proletarian theatre. Of this more later.

Bernard Shaw’s classic indictment of the middle-class theatre as an institution whose ideas were consistently twenty years behind the times is so vividly apt in Mexico that here, again, we would seem to have too good a set-up just to prove an advance conviction. There is not even the pallid liberal pretense pretense (symptomatic almost everywhere else) of an occasional serious “problem” play questioning the values and standards of their own lives, the problem usually being, should we be more broad-minded about marital infidelity or is adultery an eternal human instinct? Here the bourgeois theatre is strictly one of escape in the most elementary and mechanical sense of this act. The four playhouses are closed boxes far from the hideous circle of home. There, in happy darkness, they can be stunned into a needed coma by a series of wandering vaudeville turns under incredible greens and ambers (Madrid-New York); or a “political” revue with aimless anarchistic pot-shots at any public figure who happens to have made a nitwit of himself that week (Paris); or “modern” problem comedies from Spain reminiscent only of the early Rachel Crothers at her sententious worst; or mystery plays adapted from the British, French and American, where the illusion of being frightened out of your own depressing skin must serve as a complete compensation for the actual failure to stir you at all.

This is the fare, sickly with the odors of importation. And if ever, even as a liberal, you long for the relatively stimulating productions such as have been offered in the American bourgeois theatre bourgeois theatre by Arthur Hopkins, the Actors’ Theatre, the Theatre Guild, Guthrie McClintic and the Group Theatre, you must simply decide that you will not attend the theatre at all: which is exactly the liberal decision here.

Concentration of capital into fewer and fewer hands has reached such fantastic proportions in Mexico that there is just enough of a middle class to fill up four fair-sized playhouses for one week and then start all over again on the following Monday. The result, naturally, is that the average run of any entertainment is a week. Two weeks means a special run of luck and four weeks is a nightmare of success. Over the weekend the musical theatres often have one set of skits at 7:30 and another at 10, for, if they ran the one show three times in a day (which is the Saturday and Sunday schedule here), there simply wouldn’t be enough people to occupy all the seats. They’ve got to draw them back again and again, week after week after week.

The government or aristocratic theatre takes all the most offensive features of the London Stage Society, the Vieux Colombier under Jacques Copeau, the first steps of our own Little Theatre movement, and dance recitals of ten years ago, and blends them into one wonderful mess of recherché affectation, unsocial sterility and blatant colonial servility. All theatre events are offered as a sign of the government’s earnest “socialistic” intentions in the sponsorship of paralyzed arts and in the delibership of paralyzed arts and in the deliberate static preservation of indigenous forms: never as theatre itself, as a dynamic and belligerent projection of the contents of a belligerent projection of the contents of a living and changing world.

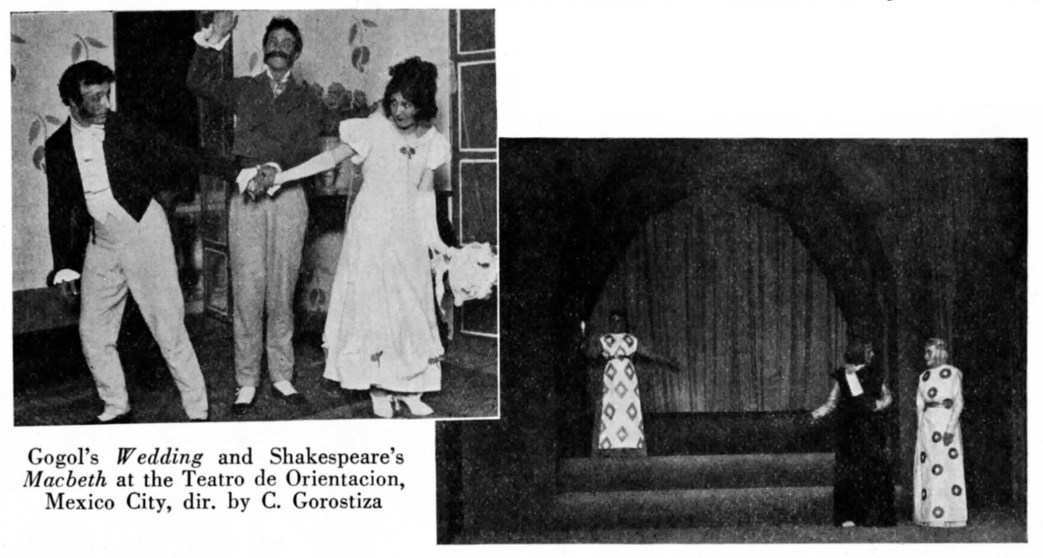

Examine this list of productions of the last five years. Kaiser’s Gas, O’Neill’s Diff’rent and Lazarus Laughed, Macbeth, Romains’ Amadeo and the Gentleman in a Row, Gogol’s Marriage, Toller’s Machine Wreckers, Cocteau’s Antigone, Moliére’s Georges Dandin and Copeau’s version of Karamazov. Not an unimpressive list by any standards. But when it is known that each was put on for one or two nights, just long enough for the best people to get acquainted with them; that they were juiceless, precious and chic experiments in style and in arty settings and costumes; that the whole program is a profound part of the essential campaign to keep the colonialized spectator ashamed and suspicious of any possible native product, then the valuelessness of the list may be understood.

Naturally, even the most consistent pressure to discourage the flourishing of the native product will never wholly succeed. So playwrights like Mauricio Magdaleno, German List Arzubide, Armando Arzubide, Fernández Bustamante, Juan Bustillos Oro and Concha Michel have intermittently come forth with dramas of social satire, high anger and revolutionary protest. But the only way to get any kind of production backing in Mexico (always excepting the workers’ theatre we are striving toward) is through the government; and the government, enchanted as it is with the opportunity to demonstrate its alleged willingness to sponsor the native and the “revolutionary” product, nevertheless takes great care not to give more than one or two performances of each play. Thus deprived of audiences and of any true sense of cultural function, it has been the undeviating experience of each such playwright that he has slipped hopelessly into a government job and begun to turn out conscious material for demagogy or, after two or three years, ceased writing plays altogether.

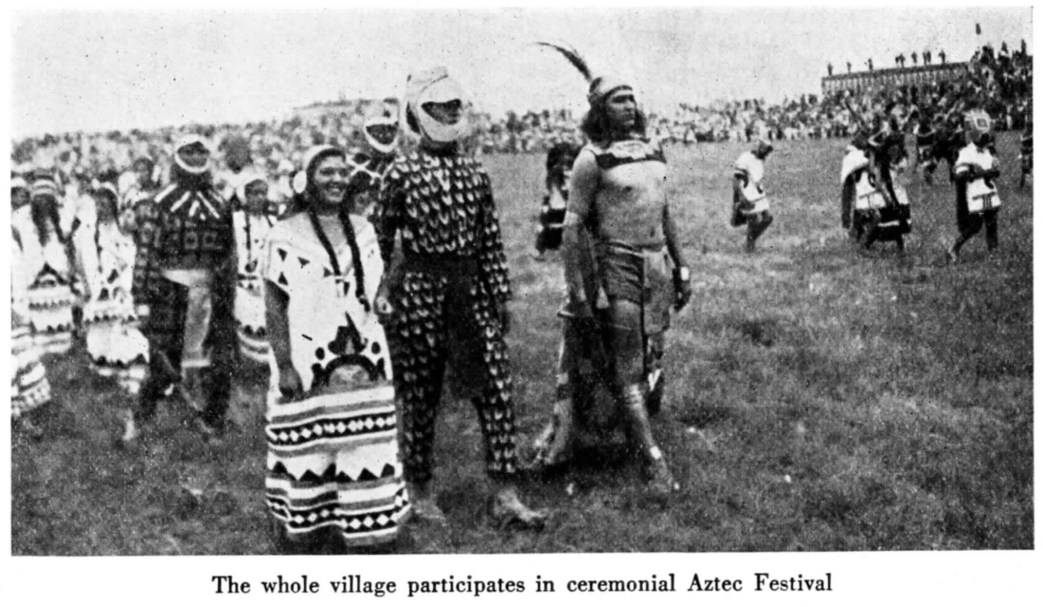

And a few times a year a concert of native dance-dramas is put on at the Hidalgo Theatre, again by the government boys. These are preposterous museum re-creations, highly offensive when it is realized that the real thing still functions brilliantly in countless villages in spite of persistent discouragement by the still powerful clergy (although this same clergy will sometimes deliberately avail itself of a pagan festival and incorporate it into the ritual of a saint’s day). The dance-drama in Mexico is a profound and important manifestation of popular theatre, but it is in no sense analogous to the new theatre, and it is a form that can scarcely be taken over and expanded before the establishment of a régime which is fundamentally dedicated to the true preservation of folk culture. Consideration thereof is accordingly pretty much out of the scope of this article.

Then what are the possibilities of a revolutionary or workers’ or social theatre in Mexico? The answer, to this observer, is that the possibilities are just as great as Theatre in Mexico the need–and the recent formation of a New Theatre group is an opening proof. The carpa is surely a brilliant base for such humor and musical cutting-up as the Theatre of Action achieved during its final period as the Workers Laboratory Theatre. The process of transformation could be an infinitely insidious one, since a tradition of sharp political irreverence is very much alive here and intensely popular. Brief depictions of the struggles of the workers’ own lives could be substituted for the dismal morality dramas with which the carpas flood the market-places around the middle of winter. And securing of audiences would be nothing of the problem it was with us in the beginning, since the theatre-going habit among workers is a fixed one here because of both the accessibility of the playhouse and the extreme cheapness of admission. And trade-union organization is so advanced in Mexico that they could supply basic support with due cultivation.

The great remaining problem is the com- bating of government demagogy—and here the important thing, of course, is recognizing and understanding it. The government not only supports a large staff of writers, artists and actors to put on little dramas about how arbitrary official compulsion settles all the differences between oppressed employees and bad bosses but also publicizes these productions on an ample scale and consistently offers them to the workers absolutely free. The large population that is sincerely hoodwinked is unfortunately balanced by an unnatural proportion of revolutionaries who have slid into fatigue and defeat over this situation. The more rapidly they determine to mature their slowly developing technique for clarifying and opposing the shrewd machinery of demagogy, the sooner we can hope in Mexico for the growth of a true workers’ theatre run by and for the workers and not by and for a willingly subservient government that presumes to call itself socialist.

The New Theatre continued Workers Theater. Workers Theater began in New York City in 1931 as the publication of The Workers Laboratory Theater collective, an agitprop group associated with Workers International Relief, becoming the League of Workers Theaters, section of the International Union of Revolutionary Theater of the Comintern. The rough production values of the first years were replaced by a color magazine as it became primarily associated with the New Theater. It contains a wealth of left cultural history and ideas. Published roughly monthly were Workers Theater from April 1931-July/Aug 1933, New Theater from Sept/Oct 1933-November 1937, New Theater and Film from April and March of 1937, (only two issues).

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v2n12-dec-1935-New-Theatre.pdf