Veteran of the African Blood Brotherhood, Socialist and Communist Parties, Richard B. Moore, writing for the N.A.A.C.P.’s Crisis magazine, with a biography of Douglass who reemerged in the mid-1930s as an important and studied figure. Moore would be expelled from the Communist Party in 1942 for his insistence on retaining Black demands in face of the ‘Win the War’ first position of the Party.

‘Frederick Douglass’ by Richard B. Moore from The Crisis. Vol. 46 No. 2. February, 1939.

February is the birth month of Frederick Douglass—the one hundred and twenty-second anniversary. A fitting tribute to the great Leader, Abolitionist and Liberator is paid here by a deep student of the life of Douglass

As the years progress, the stalwart figure of Frederick Douglass looms larger in the view of the past and the consciousness of the present. Despite the studied efforts of those in power who designedly deny to the Negro any worthy, positive, and powerful role in the past, the better to hold him in weakness and subjection in the present, the name of Douglass is increasingly heard upon the lips of the people.

Like the dreaded ghost of Banquo which appeared anon to disturb the orgies and the dreams of the murderers and plunderers, the figure of Frederick Douglass emerges out of the obscurity in which it has been craftily but vainly enshrouded. His truly massive proportions are being evermore clearly discerned, The teachings of the great Negro Abolitionist are being rediscovered and voiced anew; their unusual depth and breadth and their uncommon timelessness and timeliness are more clearly recognized.

The grand example of this fearless fighter for freedom is more highly prized for its invaluable inspiration and more boldly held forth for widespread emulation. The noble and heroic mold of the man, the effective and progressive character of his leadership, and the wisdom, scope, and power of his statesmanship are more surely and justly evaluated.

Such growing appreciation is clearly manifest in the fitting commemoration of the hundredth anniversary of his escape from the prison-house of chattel slavery by the Eastern Regional Conference of the National Negro Congress. This Conference assembled in the spirit of his great tradition in Baltimore, Md. last October, in the very city from which he made his daring and astute break for freedom on the morning of September 3, 1838. The speech of Hon. Harold L. Ickes, Secretary of the Interior, delivered on that occasion, contained these noteworthy and significant words:

“I am sure it is remembered today with pride by many citizens of this State, both Negro and white, that this is the Commonwealth which gave to the world the great orator, statesman, and courageous Negro leader—Frederick Douglass. His life, perhaps more than that of any other single individual, has been the example which has challenged Negroes to press forward and achieve what at first seemed to be impossible. The principles for: which he fought are the same as those for which you are struggling today—freedom, justice, and opportunity.”

Another notable instance of this deepening realization, not only of the past historic achievement, but also of the present progressive significance of this giant Negro figure—this titan of the great struggle that saved the Negro and the nation from the blighting scourge of chattel slavery, is the organization of the Frederick Douglass Historical and Cultural League. Founded in New York City at the Harlem Art Center, “in appropriate observance of the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Escape from Slavery of Frederick Douglass,” the League is sponsored by a number of representative persons, white as well as Negro, who are rendering significant service in many fields of activity. Its principal aims and objects are: To perpetuate the memory and to popularize the life, teachings, and achievements of Frederick Douglass. To promote the publication and wide distribution of the “Life and Works of Frederick Douglass” and of similar vital material.

Likewise expressive of this growing sentiment are the many programs which portray the role of Douglass in connection with the approaching Negro History Week, February 5-12, Lincoln’s Birthday and Douglass’s Birthday on a national scale, conducted by the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and many organizations and associated groups too numerous to mention.

As we approach, then, the one hundred and twenty-second anniversary of the birth of Frederick Douglass, it is both fitting and salutary to review the outstanding events of his life, struggle and achievement. It is necessary to understand and to apply the vital lessons of his great role in that momentous crisis of our history when the life, freedom, and advancement of four million and a half Negro slaves hung desperately in the balance, bound up inseparably with the life, liberty, and progress of all the people and, indeed, with the very existence of the nation and the democratic republic itself. This is all the more imperative, now when we are in the throes of another, still graver, world-shaking crisis in which our freedom, security, existence, and destiny are at stake.

Among Greatest Americans

Frederick Douglass occupies an unique place in history, though this is not quite fully or adequately recognized because of the powerful prejudice which still prevails in our land and beclouds the minds of most of us. Preeminent among the many great leaders produced by the Negro people in our country, Douglass also stands in the front rank of the few greatest Americans and among the truly great men of the world. This is the inescapable conclusion of any adequate study of the facts of his life and period and of a candid, unbiased estimate of his relation to the men and events of his age.

Such a study and analysis reveals that Douglass led the most sustained, consistent, and effective struggle, for the emancipation of the slaves and for the enfranchisement, elevation, and equality of the Negro people. And that struggle was of world-historic import. For it broke the fetters which not only doomed the Negro people to brutal bondage, but which also degraded all labor, nullified democracy, destroyed the peace and arrested the development of all the people of America, even as they hindered the progress of the entire world.

Yet Douglass was born a slave, denied the right to his own being, deprived of the right to education and every other human right necessary for development and achievement: Frederick Douglass began life as a chattel under a system of bondage, sanctioned by law and enforced by government, arms, and terror, which doomed him only to toil, degradation, imbrutement, and cruel subjection to the will of a master who was invested with the right of ownership and complete control over his chattel. The weight of this slave condition, the tremendous handicap which it imposed, and yet the basic consciousness, strength, and representative character that Douglass derived precisely from this identity with the slave class, must first be realized, in order to form a just estimate of the magnitude of his achievement and to grasp the true significance of his life and role.

Harriet Beecher Stowe pointed to this, in comparing him with Henry Wilson and Abraham Lincoln, when she wrote in Men of Our Times:

“Frederick Douglass had as far to climb to get to the spot where the poorest free white boy is born, as that boy has to climb to be president of the nation…”

Before he was eight years old Douglass was awakened to the cruelties and horrors of slavery by the brutal and inhuman scenes which he witnessed. Thus early was he brought to question: “Why am I a slave? Why are some people slaves and others masters?” The mystery was soon solved when Douglass learned that slaves had been stolen from Africa and that slaves who escaped to the North became free. He was now “filled with a burning hatred of slavery,” his resolve to be free was greatly strengthened. In My Bondage and My Freedom, he later wrote of this enlightenment in these pointed words:

“It was not color but crime, not God, but man; that afforded the explanation of the existence of slavery; nor was I long in finding out another important truth, namely: what man can make, man can unmake. The appalling darkness faded away and I was master of the subject.”

He Learns to Read

Fortunately Douglass was soon sent to Baltimore. Hearing his new mistress read the Bible aloud, Douglass asked her to teach him to read. Pleased with his apt progress, she soon told her husband who loudly admonished her that it was unlawful and unsafe to teach a slave to read or write. “Very well”, thought Douglass “Knowledge unfits a child to be a slave…from that moment I understood the direct pathway from slavery to freedom.”

Douglass now determined to learn to read at all costs, despite the furious opposition of his mistress. Making friends with some of the poor white boys in the neighborhood, he would stealthily secure lessons from them, paying with biscuits or pennies. With fifty cents earned by shining shoes, he bought a copy of the Columbian Orator and diligently studied the inspiring speeches of Sheridan, Pitt, and Fox. In a similar manner, he learned to write.

At the age of sixteen, Douglass was sent back to the Eastern shore where he got a different kind of education when his new master sent him to a “slave-breaker.” Douglass thus described his frightful experience during his first six months in the slave-school of Covey.

“My natural elasticity was crushed; my intellect languished; the disposition to read departed, the cheerful spark that lingered about my eye died out; the dark night of slavery closed in upon me, and behold a man transformed to a brute!”

But Douglass could not be entirely crushed. At length he determined to resist Covey and successfully fought him for two hours. Covey then gave up the attempt and never laid hands on him again. It is imperative to quote his own account of the significance of this daring deed and its liberating result:

“This battle with Mr. Covey…was the turning-point in my ‘life as a slave’…It was a resurrection from the dark and pestiferous tomb of slavery, to the heaven of comparative freedom. I was no longer a servile coward, trembling under the frown of a brother worm of the dust, but my long-cowed spirit was aroused to an attitude of independence. I had reached the point at which I was not afraid to die. This spirit made me a freeman in fact, though I still remained a slave in form.”

Several months later, Douglass planned to escape with a number of his fellow slaves, but the plot was betrayed and he was imprisoned along with several suspects. But no evidence was discovered, due to his adroitness, and he was released and sent back to Baltimore, since his master feared to lose his property and knew that Douglass would be shot by other slave-holders who regarded him as a “dangerous” character who would “incite” their slaves. Here Douglass worked in a shipyard, stealthily renewed his studies, and matured the daring and clever plan by which he escaped to the North. Arriving safely in New York, Sept. 4, 1838, Douglass was sheltered by David Ruggles, a Negro officer of the Underground Railroad. He was soon joined by his intended wife, Anna Murray, whom he married. On they went to New Bedford where he took the name of Douglass and began his new life as a freeman.

Begins Abolitionist Work

In August 1841, Douglass began his great work as an Abolitionist speaker. He attended the Anti-Slavery Convention in New Bedford, where he lived, and went on with his wife to the Convention held immediately after at Nantucket. Urged to take the platform by Wm. C. Coffin, a white Abolitionist who had heard him speak in a colored Sunday school in New Bedford, Douglass consented with many misgivings and much embarrassment at first. But his speech electrified the Convention. Parker Pillsbury described its powerful effect: “The crowded congregation had been wrought up almost to enchantment, as he turned over the terrible Apocalypse of his experiences in slavery.” Garrison was moved to “an effort of unequalled power,” and wrote himself “I think I never hated slavery so intensely as at that moment.” The entire anti-slavery movement was profoundly affected and stimulated to new life and vigor by this emergence of Frederick Douglass. One of the foremost antislavery leaders in Congress, Henry Wilson, has summarized the significance of this event in the Rise and Fall of the Slave Power:

“Anti-slavery measures had lost much of their zest and potency; meetings became less numerously attended and, consequently, less frequent; organizations, losing their interest and effectiveness began to die out. Something was necessary to revive and re-animate the drooping spirits and the languid movements of the cause and its friends. It was then, at this opportune moment…the young fugitive appeared upon the stage. He seemed like a messenger from the dark land of slavery itself; as if in his person his race had found a fitting advocate; as if through his lips their long pent-up wrongs and wishes had found a voice. No wonder that Nantucket meeting was greatly moved.”

Soon Douglass became one of the most eloquent and effective leaders if the anti-slavery struggle. He spoke throughout the North and West arousing the people to indignation and action against slavery. Often he bravely faced pro-slavery mobs and narrowly escaped being lynched several times. Outstanding among his first achievements was powerful part in the fight to secure right of Negroes to vote in Rhode Island. Douglass labored incessantly in the great campaign to free George Latimer, a fugitive slave arrested in Boston on a framed-up charge of theft. Numerous monster protest meetings were held, resolutions adopted, and petitions signed by over 65,000 persons were sent by a powerful delegation to the state legislature. Latimer was freed; personal liberty laws were enacted to protect fugitive slaves in Massachusetts; this precedent was soon followed by several other Northern and Western states. Leading the fight against Jim-Crow practices, Douglass physically resisted ejection from a car, which caused the Eastern Railroad to prevent trains from stopping at Lynn, Mass. where he lived. Public pressure upon the companies and the legislature soon forced the abolition of this practice, which was shortly followed by the repeal of the anti-intermarriage law.

After the publication of his Narrative in 1845, Douglass toured England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales, arousing widespread and powerful support for the abolition cause. Urged to remain in England and offered money with which to settle, Douglass refused to do so in order to return to carry on the fight for emancipation.

The North Star Is Started

English anti-slavery friends, however, raised the money necessary to purchase his freedom and twenty-five hundred dollars to enable Douglass to start a newspaper. Upon his return to America, this venture met with opposition from the Garrisonian Abolitionists. This dissuaded Douglass for a time, but in 1847 at Rochester, N.Y. he finally launched the North Star, which he made a powerful weapon in the struggle. The responsibility of conducting this paper and the necessity of meeting opposite views compelled him to renounce the views of the Garrisonians.

In the crisis now developing in the country, Douglass played a signal role, striking forceful and telling blows. In a powerful reply to Henry Clay, delivered in Boston at Faneuil Hall in June 1849, he sharply denounced the revived Colonization Movement, the pro-slavery war against Mexico, the prejudice against color, and created a sensation when he declared: “I should welcome the intelligence tomorrow that the slaves had risen in the South.” At the Broadway Tabernacle in New York in 1850, he succeeded by the sheer power of his eloquence and wit in quelling a pro-slavery mob. His Fourth of July Oration in Rochester in 1852 was a masterful philippic. At the meeting of the Anti-Slavery Society in New York in 1853, he made a keen analysis and forecast of the political situation revealing the development, policy, and machinations of the slavery party: “Old party ties are broken. Like is finding its like on either side of these issues, and the great battle is at hand.”

Douglass bravely resisted the Fugitive Slave Law, maintaining his home at Rochester as a station of the Underground Railroad. Fearlessly he denounced the Dred Scott decision: “We can appeal from this hell-black judgment of the Supreme Court, to the court of common sense and common humanity.” Speaking at the celebration of West Indian Emancipation the same year, Douglass declared this to be “the most interesting and sublime event of the nineteenth century.”

Douglass aided John Brown, but did not go with him to Harper’s Ferry, because of his conviction that he had other vital work to do for the abolition of slavery. In this he is proved to have been correct, for he rendered invaluable service in uniting all the progressive forces of the country against slavery and in securing the election of Lincoln. At Geneva, N.Y. on August 1, 1860, Douglass delivered a speech which proved his consummate political acumen and genuine statesmanship:

“The abolition idea is still abroad, and may yet be made effective. It has no powerful party distinctly committed to its realization, but has a party distinctly committed to a policy which the people generally think will do certain preliminary work essential to the overthrow of slavery…while the Republican party is far from an abolition party, a victory gained by it in the present canvass will be a victory gained by that sentiment over the wickedly aggressive pro-slavery sentiment of the country…The slaveholders know that the day of their power is over when a Republican president is elected…the threats of a dissolution of the union in case of the election of Lincoln, are tolerable endorsements of the anti-slavery tendencies of the Republican party; and for one, Abolitionist though I am, and resolved to cast my vote for an Abolitionist, I sincerely hope for the triumph of that party over all the odds and ends of slavery combined against it.”

Urged Negro Troops

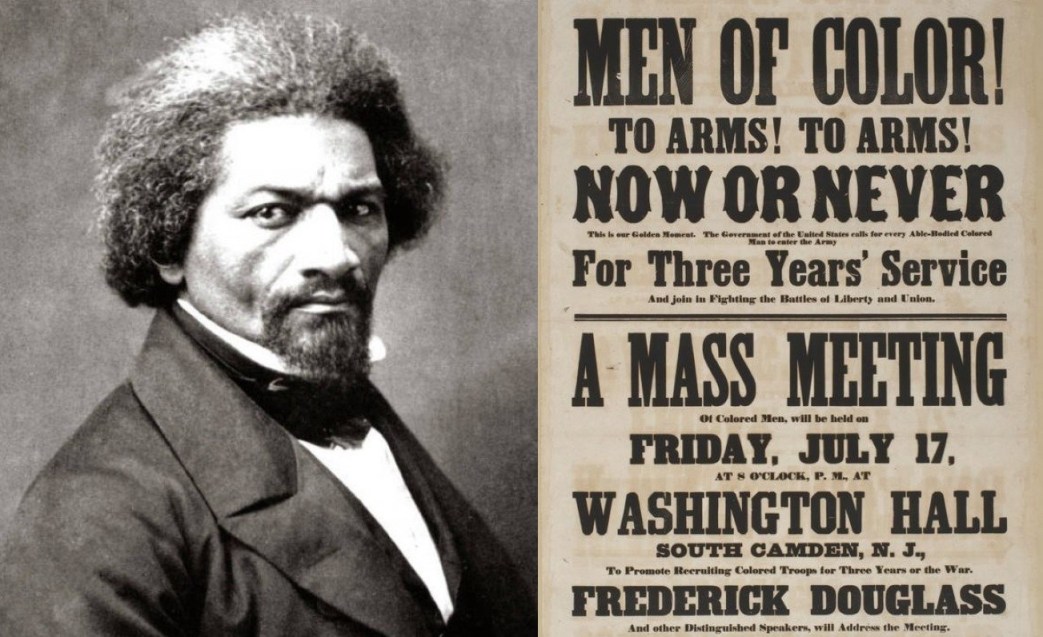

Yet Douglass criticized constantly and sharply all the illusions, weaknesses, vacillations, and attempted compromises of Lincoln and the Republican government with the Slave Power. From the very outbreak of the Civil War he worked incessantly to awaken, arouse, and mobilize a powerful public sentiment in the North for a vigorous prosecution of the war. “Make the war an abolition war” and “Employ the arm of the Negro” were his ringing slogans. When this necessity at last began to dawn upon the Administration and Governor Andrew of Massachusetts secured permission to raise two colored regiments, the 54th and 55th, Douglass issued on March 2, 1863, his stirring and powerful appeal: “Men of Color, To Arms!” But when by August 1, the government failed to keep its promise to put the Colored soldiers on an equal footing, giving them only half pay, making no. promotions, and failing to act to prevent their horrible treatment when captured by the Confederates, Douglass wrote a sharp protest to Major Stearns in which he declared his refusal to enlist any more Negro troops until common justice would be accorded them.

Major Stearn’s reply urged Douglass to confer with President Lincoln at the White House. He was cordially received by the President who listened patiently to his protest, and stated the reasons why he deemed it necessary to go slowly, and promised some remedial action shortly. Though not entirely satisfied with his reasons, Douglass was thoroughly impressed with Lincoln’s honesty, and hence renewed recruiting.

When the Emancipation Proclamation came at last, Douglass immediately began a campaign for the enfranchisement of the freedmen. Following the foul assassination of Lincoln, Douglass fought during the entire Reconstruction period for the full enfranchisement, protection, and equality of the Negro freedmen. Leading a delegation of representative Negro citizens to interview President Andrew Johnson, Douglass was thus among the very first to strive for these rights. Andrew Johnson harangued and rebuffed the delegation, but he was forced to reveal his true reactionary policy. Whereupon Douglass and the delegation answered the President in an appeal addressed to the nation which declared: “Men are whipped oftenest who are whipped easiest. Peace between races is not to be secured by degrading one race and exalting another…but by maintaining an equal state of justice between all classes.”

Spurning the base appeals of those prejudiced and craven delegates who urged him not to attend the National Loyalists’ Convention held in Philadelphia in September following, Douglass went manfully there and did a great deal to win the Convention to declare for the enfranchisement of the Negroes and the protection of white and black loyalists in the South.

Views on Labor

At the Convention of Colored Men held in Louisville, Ky., September 24, 1883, Douglass delivered an address to the people of the United States. On the labor question, Douglass made this weighty statement: “Not the least important among the subjects to which we invite your earnest attention is the condition of the labor class in the South. Their cause is one with the labor classes all over the world. The labor unions of the country should not throw away this colored element of strength…It is a great mistake for any class of laborers to isolate itself and thus weaken the bond of brotherhood between those on whom the burden and hardships of labor fall…As the laborer becomes more intelligent he will develop what capital he already possesses—that is, the power to organize and combine for its own protection. Experience demonstrates that there may be a slavery of wages only a little less galling and crushing in its effects than chattel slavery, and that this slavery of wages must go down with the other.” Answering a charge that the Convention “would disturb the peace of the Republican party,” Douglass affirmed: “If the Republican party cannot stand a demand for justice and fair play, it ought to go down. We were men before that party was born, and our manhood is more sacred than any party can be. Parties were made for men, not men for. parties.”

Replying to the question: Why colored conventions? Douglass declared: “Because the voice of a whole people, oppressed by a common injustice, is far more likely to command attention and exert an influence on the public mind than the voice of single individuals and isolated organizations…If there were no other grievance than this horrible and barbarous lynch law custom, we should be justified in assembling as we have now done, to expose and denounce it.”

Yet Douglass also counselled in his address on the Twenty-First Anniversary of Emancipation: “There is but one destiny, it seems to me, left for us, and that is to make ourselves and be made by others a part of the American people in every sense of the word…We cannot afford to set up for ourselves a separate political party, or adopt for ourselves a political creed apart from the rest of our fellow citizens.”

Douglass held several public offices, including that of Marshal of the District of Columbia and Minister to Haiti. Yet he always used his high position to advance the cause of his oppressed people and of liberty for all mankind. He was signally honored by the Republic of Haiti when named as its Commissioner for the World’s Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in 1893. There he delivered an able speech and lecture on the Negro nation which struck: the first shattering blow against chattel slavery.

The mistakes of Douglass were so few and so quickly corrected that he must be adjudged a most sagacious leader. Till the end of his life in 1895, he continued to deserve the title of Liberator of His People and Great Champion of Human Liberty. Hence the tribute made by Henry Wilson: “In him not only did the colored race, but manhood itself find a worthy representative and advocate…His life is in itself an epic which finds few to equal it in the realms of romance or reality.”

May we not derive great inspiration from his heroic example and clear light from his sage teachings, in order to go forward to meet the stern challenge of the present crisis, when fascism menaces everything that we hold dear? Can there be any doubt as to where Douglass would stand in this great battle, how he would lead and how he would fight?

Well may we say of him, as he said of the great pioneer Abolitionist, Garrison: “Let us teach our children the story of his life; let us try to imitate his virtues, and endeavor as he did to leave the world freer, nobler, and better than we found it.”

The Crisis A Record of the Darker Races was founded by W. E. B. Du Bois in 1910 as the magazine of the newly formed National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. By the end of the decade circulation had reached 100,000. The Crisis’s hosted writers such as William Stanley Braithwaite, Charles Chesnutt, Countee Cullen, Alice Dunbar-Nelson, Angelina W. Grimke, Langston Hughes, Georgia Douglas Johnson, James Weldon Johnson, Alain Locke, Arthur Schomburg, Jean Toomer, and Walter White.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/sim_crisis_1939-02_46_2/sim_crisis_1939-02_46_2.pdf