Lozowick (1892-1973), a central figure in the world of radical arts, was born in Ludvynivka Ukraine and studied at the Kiev Art School from 1903 to 1906 when he came to the United States and continued art studies at Ohio State University. Louis traveled extensively in post-war revolutionary Europe before returning to the US in 1924 where Lozowick lectured on modern Russian art for the Société Anonyme. In 1926 he joined the executive board of the New Masses, became secretary of the American Artists’ Congress and was active in the John Reed Clubs. His work appears in many issues of New Masses. Known for his WPA-era paintings including murals, he exemplified the Precisionist movements.

‘Louis Lozowick: Revolutionary Artist’ by Joseph Freeman from The Daily Worker. Vol. 3 No. 58. March 20, 1926.

THE prophetic eyes of Marx foresaw that art could not long escape the effects of machinery and the factory system. He posed the problem, and answered it, fifty years before the painters and poets of Europe became aware that the revolution in production demanded a revolution both in the content and form of their arts. In the “Critique of Political Economy” Marx asked:

“Is the view of nature and of social relations which shaped Greek imagination and Greek art possible in the age of automatic machinery, and railways, and locomotives, and electric telegraphs?…All mythology masters and dominates and shapes the forces of nature in and through the imagination; hence it disappears as soon as man gains mastery over the forces of nature. What becomes of the Goddess Fame side by side with Printing House Square (or Times Square)?…Looking at it from another side: is Achilles possible side by side with powder and lead? Or is the Illiad at all comparable with the printing press and steampress?”

Long after Marx’s general viewpoint became a dynamic factor in the political and economic life of the world, painters continued to evade the mechanical world about them. Their revolt against the ugliness of factory towns manifested itself in landscape paintings; it is a noteworthy fact that not until the rise of the dirty factory town did western European painters discover the profuse beauties of the country. They sought relief from smokestacks in trees, from trains in birds, from slums in fields. Consciously or unconsciously the “mythology” (i.e., Weltanschauung) of 19th century painters was derived from Rousseau and the classical political economists. Its keystone is laissez faire; its aesthetic maintains that the artist is a divine, unique creature, above social classes and unconcerned with the contemporary world. His chief subjects are nature and the individual man.

By the first decade of the 20th century machinery had so transformed the western world that the sysmographic temperaments among bourgeois artists could no longer fail to register the earthquake that had been shaking the world for over a century. Futurism, cubism and other movements attempted to break away from the traditions of representation and agriculture in painting, and to achieve abstraction in form and modernity in content.

These early revolutions in art were one-sided; they were general strikes whose force was concentrated on this or that isolated factor of the old aesthetic. They succeeded in weakening the old traditions. They were also rich experiments, containing the germs of principles which had yet to be grasped and synthesized. They were, so to say, the “1905” of modern painting, a preparation for the more significant “1917.”

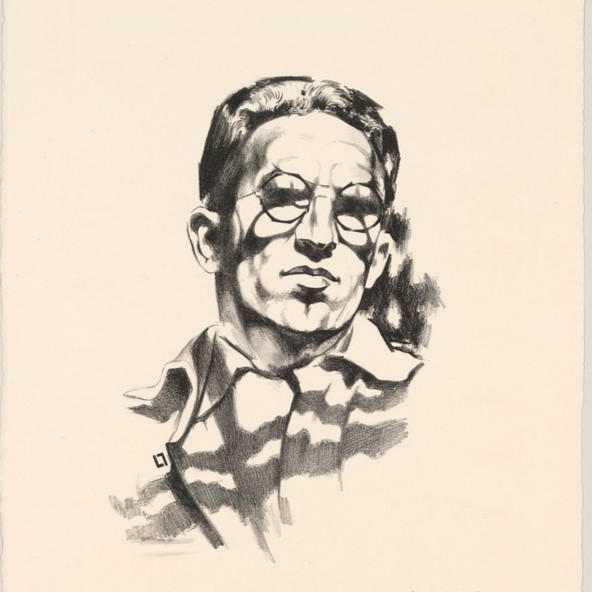

THE first American synthesis of modern tendencies in painting has been made by Louis Lozowick, whose canvasses and drawings have just been exhibited in New York. Without attributing any mystical significance to “innate racial tendencies,” it is nevertheless interesting to observe that Lozowick is a Jew of Russian birth and American education. The importance of this personal organization of backgrounds is reflected — among other qualities—in the powerful and original work of the artist. His subject matter is American; his Weltanschauung is permeated with the revolutionary ideas which historically have been most vital in Russia.

To understand the importance of Lozowick in American art it is necessary to realize that here we have a painter who is conscious and deliberate in his work. He combines intellect with craftsmanship; he thinks not with his hands alone, but is capable of advancing the theories of his art, and to grasp the true relation of art in general to society in general.

There is a tendency among American art critics to consider that “love for the remote” is the essential characteristic of the American artist. Both in theory and in his remarkable paintings, Lozowick stands not for the remote, but for the immediate: for the visible world of machinery, skyscrapers, cities. His mind is steeled by Marxism. This in itself, of course, is not sufficient to make a man a great painter; but it has its effect on his thought, subject matter, form, and attitude toward his work. As opposed to the bourgeois notion of the artist as a priest (a notion maintained partly as a compensation for the miserable pay doled out to genuine artists in capitalist civilization) Lozowick is one of those who looks on the artist as a worker.

In this, and in his respect for craftsmanship, Lozowick has qualities in art equivalent to the qualities exhibited by the advanced proletariat in society. He is thus poles apart from other painters who have tried to adapt modern forms to modern subjects; for whereas these see in the metropolis, factory and street nothing but confusion, chaos and contradiction, Lozowick sees underneath these superficial aspects the essential order and organization inherent in machine civilization as such.

Lozowick is permeated by the significant forces of the 20th century. He has not tried to evade them; instead he has understood them, accepted them, and found an aesthetic equivalent for them in painting. Against the old art of sentimentalism, adoration of the individual, in–and nostalgic longing for the past, he represents an art that is impersonal, collective, precise, and objective; in this he is as truly representative of the scientific spirit of this age as the medieval painters of the metaphysical spirit of their age.

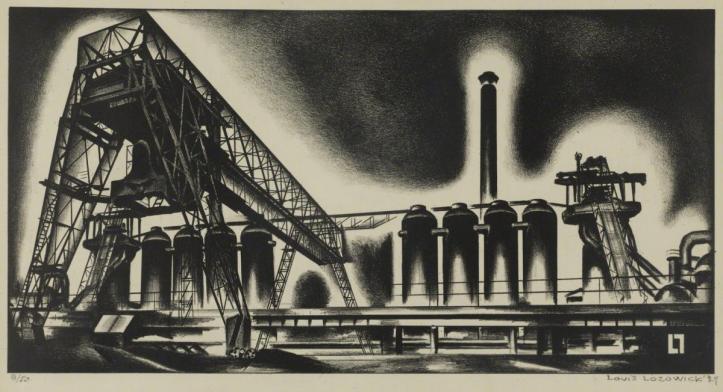

Having realized the basic fact that a living art must seek its content and form in the living world, Lozowick has gone for the content of his paintings to the American city which represents the highest advance so far of machine civilization. His themes are the skyscrapers of New York, the steel mills of Pittsburgh, the grain elevators of Minneapolis, the copper mines of Butte, the lumber yards of Seattle. These canvasses of cities—no two of them alike—are thoroughly saturated by the terrific energy of modern America, its gigantic engineering feats and colossal mechanical constructions. In his critical writings Lozowick has stated his position clearly enough. He declares:

“Every epoch conditions the artist’s attitude and the manner of his expression very subtly and in devious ways. He observes and absorbs environmental facts, social currents, philosophic speculation and then chooses the elements for his work in such fashion and focuses attention on such aspects of the environment as will reveal his own aesthetic vision, as well as the essential character of the environment which conditioned it.

“The dominant trend in America today, beneath all the apparent chaos and confusion, is towards order and organization which find their outward sign and symbol in the rigid geometry of the American city, in the verticals of its smokestacks, the parallels of its car tracks, the squares of its streets, the cubes of its factories, the arcs of its bridges, the cylinders of its gas tanks.”

The clarity of Lozowick’s critical perceptions is matched by the superb craftsmanship which he brings to his painting. With a mathematical pattern as a basis, he builds up paintings that at once contain the appearance of American cities and capture their titanic rhythm. The paintings are architectural, giving the effect of plans for vast building projects. They are also representative, having associative elements which’ make it easy to recognize New York or Pittsburgh or Cleveland. At the same time they have purely formal, plastic qualities; the arrangement of masses, lines, planes and colors make them self-contained works of art.

Many artists who are bourgeois in their ideology are breaking under the strain of the contradictions between the old art and the new machine civilization. Lozowick stands in the first rank of those who have solved this conflict by evolving an art based on machinery. He has thus been able to solve the subsidiary conflict between “pure” art and “commercial” (i.e., practical) art. Par from despising practical art, he has carried his theories to one of their logical conclusions by creating designs for posters, theatres, advertising, magazines, etc., which are based on various elements of the machine. In the field of applied design of a purely modern character he has been a pioneer; in his whole outlook, his themes, his form, he is a revolutionary in the truest sense.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1926/1926-ny/v03-n058-supplement-mar-20-1926-DW-LOC.pdf