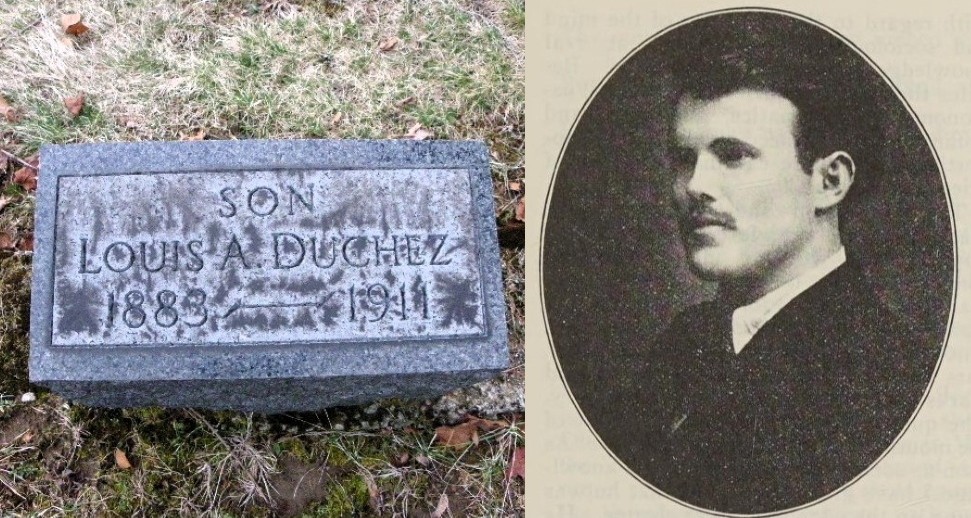

Louis Duchez, son of a Communard, was a proletarian intellectual raised in the coal mines of Ohio; a poet, labor organizer, journalist, and revolutionary Socialist who assumed a leading role in our movement during his too short life, dying at just 27 in 1911.

‘Louis Duchez Dies at Father’s Home’ from The New York Call. Vol. 4 No. 208. July 27, 1911.

Sickness of Many Months Ends in Death of Well-Known Socialist.

EAST PALESTINE, Ohio, July 26. The Socialists of this section are mourning the loss of Louis Duchez, the well-known writer and agitator, who died at the home of his father last Monday night. The cause of his death has not been definitely ascertained, as the specialist who was called would not name the affliction of the windpipe which slowly choked Duchez to death.

His wife was in constant attendance upon Duchez, but her loving care was in vain.

The news of the death of Louis Duchez will come as a shock to every member of the Socialist party.

In the death of Duchez the party and the movement has lost one of its most original and brilliant thinkers. Many will remember the vivid articles that have appeared in the columns of The Call from his pen. They will remember that the articles had that peculiar quality that expressed his thought with a clarity that few writers can claim.

The Call was not the only paper to which he contributed, and there is no important Socialist or labor paper in the country that has not published articles from him.

But his writings gave no index to his capacity, for, like all other workers, the necessity of earning a living kept him from expressing the thoughts that crowded his brain. On this account only those who were fortunate enough to call him friend, and to listen to his conversation, were able to form an idea of his ability.

Duchez was, a revolutionist by inheritance his father, who survives him, having been through the heroic struggle of the Paris Commune. For many years Duchez worked in a coal mine, where his inherited and instinctively rebellious spirit was disciplined and received the indelible impression that, were his fellows but to organize, the world would be theirs for the taking.

From the mines he took up journalism, serving as city editor on two papers, and in other capacities for a number of years. He enlisted in the United States Army, and went to the Philippines, where he saw active service in the Spanish-American War for over a year. At one time he was a cattle drover, and took various kinds of work as it turned up.

But, despite his varied experiences, often of the hardest possible nature, his almost child-like simplicity of thought was never warped with the slightest touch of that cynicism that modern brutal conditions so easily engender. It was this very simpleness and directness of thought that often prevented listeners understanding his meaning. With this simplicity of thought, however, went a subtlety of thought rarely equaled.

For several months past some of his friends had urged him to leave New York City, where he was working on the staff of The Call. The climate was unsuitable, and he was sick, and growing constantly worse. His extreme interest in the movement kept him in city, however, against his better judgement, and there is no doubt that death was hastened by his staying.

Yesterday The Call received the following letter from him, perhaps the last he wrote, dated July 22, but not mailed until after his death:

“East Palestine, Ohio, July 22.

“Dear Comrade Smith–Herein I send you that police card. I am completely down and out so far health is concerned, so will cut it short.

“Am planning to go further West. If I stay here I would be a complete wreck in a short time. New York has certainly put my health on the bum.

“Sincerely, DUCHEZ.”

Duchez was married only a few months ago, and there is no doubt that the constant care afforded him by his Comrade wife was largely responsible for his comfort and happiness during his final illness. That the marriage was exceptionally happy those who knew them can testify.

For the last year Duchez had had is preparation a book dealing with various aspects of the Socialist movement, it is hoped that it may be sufficiently advanced to enable its publication. In his death all Socialists and friends have lost a dear Comrade, and Shelley’s immortal tribute to Keats makes but a fitting end to the painful story of his death:

“And he is gathered to the kings

thought,

Who waged contention with their

decay,

And of the past are all that cannot

away.”

The New York Call was the first English-language Socialist daily paper in New York City and the second in the US after the Chicago Daily Socialist. The paper was the center of the Socialist Party and under the influence of Morris Hillquit, Charles Ervin, Julius Gerber, and William Butscher. The paper was opposed to World War One, and, unsurprising given the era’s fluidity, ambivalent on the Russian Revolution even after the expulsion of the SP’s Left Wing. The paper is an invaluable resource for information on the city’s workers movement and history and one of the most important papers in the history of US socialism. The paper ran from 1908 until 1923.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-new-york-call/1911/110727-newyorkcall-v04n208.pdf