Historic leader of the Turkish Communist Party Bekar Ferdi analyzes the re-organization of Islamic leadership in the aftermath of Turkey’s abolishment of the Caliphate.

‘The Political and Social Movement in Arabia’ by Bekar Ferdi from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 6 No. 71. November 4, 1926.

The Political Situation in the Moslem Countries on the Eve of their Fights for Independence.

With the exception of Persia and Afghanistan, all the Moslem countries in the Near East belonged at one time to the Turkish Empire. The imperialist Great Powers had especially after the Young Turk revolution in 1908 carried on the same policy of disorganisation as they had towards Turkish rule in the Balkans. They exploited the feelings of enmity which divided the Turks from the Arabs in order to rouse the latter against the Government of Constantinople. The groups of feudal leaders and landowners who were in their pay were compelled to cultivate a certain spirit of independence in the people in order to promote their separatist tendencies. Thus the French and the English, quite unintentionally, were the first to arouse the Arabian nationalism which they are frequently obliged to combat.

When, in 1920, the Turks, in order to defend their independence against the victorious imperialists, took up arms against the decision which condemned Asia Minor to be a colony, the peoples of Iraq, Syria and the Hedjaz etc. were still living on the remnants of their illusions of freedom. The Turkish yoke had for so long been represented to them as the source of all their troubles, that the mere fact of the establishment of an independent administration was in their eyes the most certain guarantee of their future happiness. The presence of the imperialist armies of occupation did not in the least disturb their happiness, for these armies had delivered them from the humiliating rule of the Turks. The intruders were regarded as saviours.

At first the nomadic tribes fought alone against the presence of these military forces. The citizens of the large centres, the religious castes (Sheiks) and the feudal landowners not only enjoyed every honour but they had the possibility of raking in large gains, in that, side by side with British and French firms, they participated in their lands being turned to profitable account. The situation of the middle classes, including the intellectuals who at one time had co-operated in the Ottoman administration, was quite different. The ruthless methods of exploitation and plundering resorted to by the foreign capitalists under the protection of the armies of occupation, deprived them of all possibility of further development and turned them into mere wage-earners.

The events in Turkey necessarily made a deep impression on this population. The great success of the Turkish nationalists in 1922 stirred up in these subjugated masses the feeling for national liberation which had not yet been awakened. This accounts for the revolts which followed one another and which are far from being at an end.

The Imperialist Intrigues.

In this situation it became evident that there was every- where a tendency to united effort and for a higher body to be created which would be capable of carrying through its authority. The activities of those who were fighting against imperialism might with great advantage have been conducted by the Caliph under the auspices of Turkey. In the meantime however the Kemalists had abolished the Caliphate in the interests of their internal policy.

This historical reform filled the imperialist Powers with hope. Each of them thought there was a prospect of its being able to pay a creature who was to play the part of Caliph, so as once and for all to establish the authority of that imperialist Power in the Moslem world.

Italy made efforts to win over the famous leader of the Senussi to her side, France patronised Yussuf, the treacherous Sultan of Morocco and counted on being able, in certain Syrian circles, to exploit the fact of the Ottoman dynasty being turned out of Turkey.

As regards Great Britain, she had had her man ready for a long time. In accordance with an old tradition, she relied in Persia on the family of the Kadjars, and in Arabia supported the Hashimids against the Turks. She placed great hopes on the present head of the family, Hussein, who had received the Kingdom of Hedjas as a reward for the services he had rendered the British army against the Turks during the great war. Furthermore, each of his sons had been made king of one of the mandatory territories (Iraq, Trans-Jordania, etc.).

But the well-tried policy of Great Britain met with reverses both in Persia and in Arabia. The servile attitude of Hussein towards Great Britain had discredited him in the eyes of the population to such an extent that a man, coming from the deepest deserts of Arabia, the religious head of the Wahabiti and King of Nedzd, easily conquered the Kingdom of Hedjas and deprived the corrupt Hashimid of the throne.

With admirable pliancy, British diplomacy cast aside the one who had been defeated and tried to approach Ibn Saud. He however had good advisers and knew what he was doing. After the overthrow of the Caliphate, the powerful organ of the Indian Moslems, the “Committee for the Caliphate” turned to this undisputed leader of Arabia and supported him with all the means in its power. The intrigues of Great Britain only succeeded in detaching a few renegades from this committee. There can be no doubt today as to the anti-imperialist tendencies of the new King of Hedjas. When Ibn Saud concluded a treaty with the British Empire, recognising its sovereignty, it was thought that he had been bribed. It soon transpired however that the treaty only secured him advantages and that Ibn Saud had not undertaken any compromising obligations.

The Conference at Cairo.

The agents of Great Britain who clearly understood the situation, continued their intrigues against him. Their aim was to thrust Ibn Saud and his adherents on one side and to solve the question of the Caliphate in favour of one of the princes who was under the influence of Great Britain. The person they had in view was none other than King Fuad of Egypt. He was persuaded to summon a meeting of the Moslem theologians of all nationalities to Cairo. in order to solve the question of the Caliphate before the Congress which the followers of Ibn Saud intended to convene in Mecca on the occasion of the Pilgrimage in 1926. At the end of that winter a meeting of clerical dignitaries without any authority did actually take place in the Egyptian capital. The nationalist Press unanimously denied that the delegates possessed the qualifications necessary to enable them to pass resolutions. In any case the greater part of the invitations remained unanswered. Only a few of the congregations of the countries dominated by Great Britain, France and Italy sent representatives.

The Aims of the Congress in Hedjas.

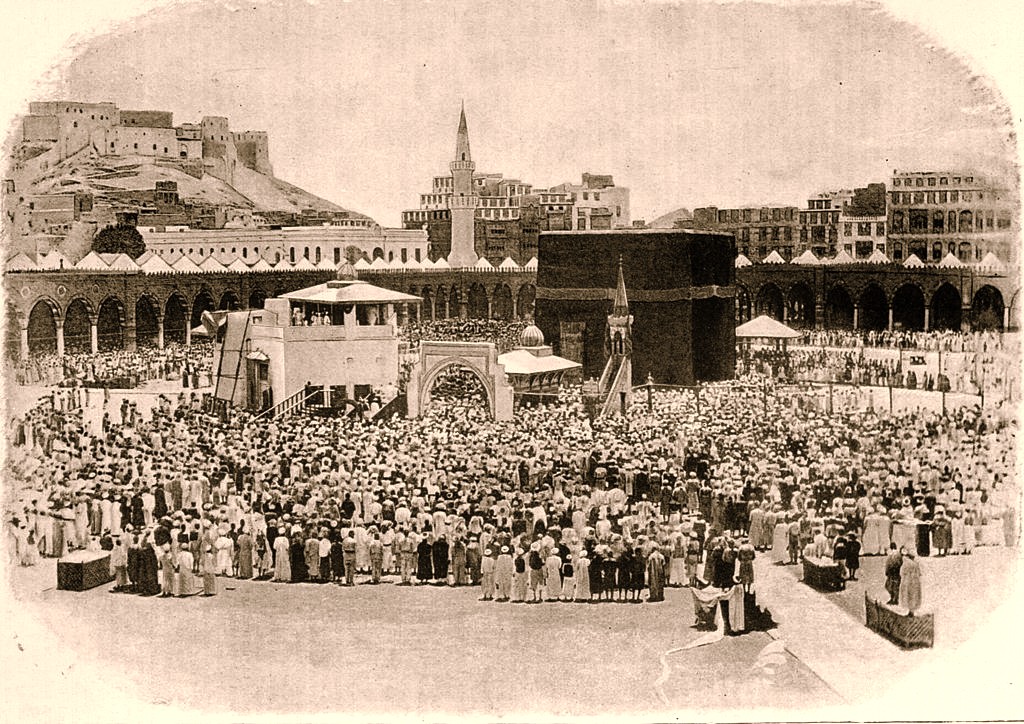

In the programme of the Congress of Mecca the question of the Caliphate was not even hinted at. The aims they had set themselves were far humbler ones. It was merely a case of interesting the whole Moslem world in the fate of Hedjas which is regarded as the common property of all the faithful and to ensure good conditions of safety and hygiene for the pilgrims, guaranteed by the support of all the Moslem States.

The imperialist circles had at first spread rumours to the effect that Turkey, Afghanistan and the Moslem Republics of the Soviet Union were not to be invited to these discussions. The idea was to rouse the suspicion that the imperialists had a hand in it. Facts however soon showed that these assertions were an invention from beginning to end.

The speculations on religious splits in Islam proved vain. The invitations were responded to with a characteristic unanimity. There can be no doubt that the various interpretations of Islam which, until a short time ago, were the cause of embittered fights, have now been placed in the background owing to the increased desire of the Moslem peoples to free themselves from the imperialist yoke, for which purpose a strengthening of the bonds of solidarity is necessary. In all Moslem countries the conviction prevails that Hedjas is destined to be a centre of support for all national fights for liberation, as is at present the case with Syria.

The Results of the Congress of Mecca.

More than 80 delegates took part in the Congress, apart from 157 invited guests. The most important Moslem States, including Turkey, were represented. Ibn Saud himself opened the Congress and made a speech in which he begged the delegates to exercise complete freedom in bringing forward and passing resolutions with regard to what seemed to them useful for the well-being of the Moslems. He only requested them not to touch on those questions which were a permanent matter of dispute between the various Moslem sects. Furthermore he asked them not to concern themselves with international politics.

The question with regard to visiting the Holy Places was discussed at greatest length. According to the doctrine of the Wahabiti, it is heathenish to cover the holy sepulcres with a roof and to throw oneself on the ground before these memorials. As a matter of fact, as soon as they had conquered the Holy Ground, the Wahabiti demolished some of these monuments. For the same reasons, the inhabitants were indignant at the traditional special caravan from Egypt. These incidents served the British Press as a pretext for carrying on a violent campaign against the Wahabiti, in order to make an attempt once more to sow dissension among the Moslems.

The Congress appointed a special commission composed of representatives of all the points of view, which was to regulate all the questions of religious customs and traditions. The King of the Hedjas undertook to submit to the decisions of this competent commission and to carry them through. The commission was also instructed to find a basis for an understanding and an amalgamation between all the sects of Islam.

The question was also discussed at length as to whether this Congress should be given a permanent character and should set up organs for propaganda in various countries. This question was not settled in the affirmative. But the mere fact that it was resolved to hold a similar congress every year in Hedjas or in some other independent Moslem State (Turkey, Afghanistan, etc.) and to set up a kind of general secretariat with Chekib Arsbaan (a representative of Arab nationalism who is well known in the diplomatic circles of Europe) as secretary, proves that this arrangement is destined later to be transformed into a permanent organisation.

At the suggestion of the Turkish delegate, the Congress resolved that the statutes worked out for Turkey, Afghanistan and Yemen should only be given legal validity after they had been passed by the governments in question. This document provides that everything possible should be undertaken in order to transform Hedjas into a modern and flourishing country and that efforts should be made to create, through general cooperation, all the conditions necessary for the social, religious, economic and literary development of the Moslem nations.

A resolution of great economic importance was that regarding the railway line of Hedjas which, in its time, had been constructed by the Ottoman Government out of the money collected in all Moslem countries by voluntary contributions. After the great war, this line was appropriated partly by France and partly by Great Britain. The Congress resolved to demand that it be returned to the Mussulmans and that, in view of the fact that it is the common property of all Mussulmans, the Government of Mecca should be entrusted with its management The Congress further resolved that each Moslem people should contribute towards the construction of a new railway between Mecca and Medina in order to facilitate the pilgrimages.

A whole number of sanitary measures was resolved upon in order to ensure good hygienic conditions for the hundreds of thousands of the faithful, who come to visit the Holy Places.. The most important point is the provision of wholesome drinking water for Mecca and Jedda, the building of large hospitals etc. For this purpose, all the religions funds which are at present in the various countries, are to be centralised in Mecca.

Before it separated, the Congress passed a resolution of a political nature, which was not confirmed by the delegates of Turkey and Afghanistan, doubtless out of diplomatic considerations. It was a question of the restitution of the districts of Akaba and Maan to the Kingdom of Hedjas.

The statement made by the Indian delegate Shevket Ali in the name of the Mussulmans who are subject to the imperialist rule, was particularly impressive. He asseverated that the peoples at present languishing under the foreign yoke are always prepared to give every material and moral support to the independent Moslem States in their struggle to increase the power of Islam.

To summarize, it may be said that the Congress of Mecca was crowned with complete success. The intention is that it should be the first effective act of solidarity of the Moslem world which is progressing towards its political evolution and national liberation. It has made it possible for the Turks to break down the barrier which had been formed between them and the rest of the faithful in consequence of the secular revolution carried through by the Kemalists, and to resume their place in the great family of the Moslem peoples.

The Communist Point of View.

No one can deny the enormous importance of these movements from the point of view of the world revolution, movements which are stirring to their very depths hundreds of millions of human beings, who are enslaved by the imperialist Powers, movements which may one day shatter the foundations ‘of imperialism in Asia and Africa.

It is a matter of course that these fermentations have nothing in common with the proletarian movement and with Communism, if they are estimated according to their social content and their political and economic aims. What we are witnessing are the efforts of the petty bourgeoisie of these countries, supported by the masses of the peasantry, to secure, for themselves the necessary conditions which will enable them to develop freely.

It is therefore necessary for the Communists to be very careful as to the attitude they take with regard to these movements. In so far as these movements are anti-imperialist factors, we must support them in every way that depends on us, in order to ensure their success. We must however never forget either their bourgeois nature nor their predominantly capitalist tendency and we must not allow ourselves to be taken in tow by them but must carefully preserve the independence of the communist organisations. Our Communist Parties in Turkey and Palestine take these peculiarities into consideration and are following a perfectly correct line in this respect.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly. Inprecorr is an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1926/v06n71-nov-04-1926-Inprecor.pdf