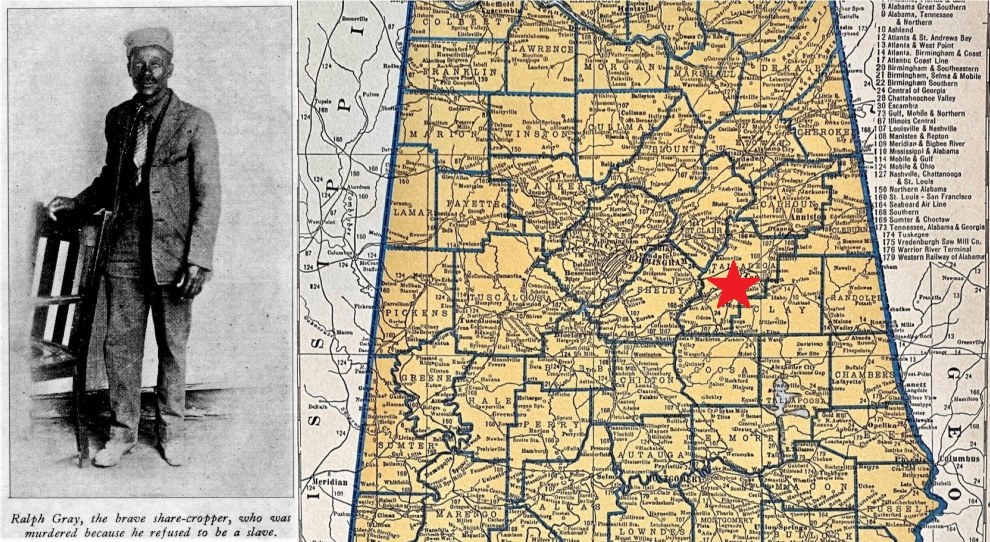

The desperation of real hunger leads to armed resistance by the share croppers of Tallapoosa County, Alabama and the death of leader Ralph Gray and an undetermined number of others.

‘A War from Bread’ by Jim Allen from The Daily Worker. Vol. 8 No. 175. July 22, 1931.

THE armed struggle now raging in Tallapoosa County, Alabama—in the heart of the Black Belt—between Negro croppers, tenants and poor farmers and armed posses of deputies and white landlords is a desperate struggle against starvation and feudal tyranny.

Led by the Croppers Union, the Negro toilers, supported by the poor whites in the section, are defending themselves with breech-loader and shotgun against a raging, terroristic band of 600 white landlords, deputies and business men mobilized from Tallapoosa and Lee Counties and armed with machine guns and rifles. While only one Negro share-cropper—Ralph Gray—is definitely known to have been killed and six others wounded, while defending Gray in his cabin against a posse of deputies who had mortally wounded him in an encounter on the road, scores of other croppers lie wounded in retreats in the backwoods. Of the thirty-two Negro toilers thrown into the Dadeville jail four of those wounded have “disappeared.” According to Police Chief Wilson they have gone “cutting stove wood”—with a lynch mob accompanying them. The lynch mob is on the rampage—terrorizing and burning. The Mary Church, in which the Negro toilers held a Scottsboro protest meeting last Wednesday night, was burnt to the ground in broad daylight and the torch has been applied to a number of cropper’s cabins, with the deputies reporting that they did “not know whether they were occupied or not.”

The croppers are putting up a stiff fight for their lives. Sheriff J.K. Young was critically wounded and two other officers were wounded in a gun battle when the Negroes were defending themselves and the mortally wounded Gray from the lynch mob. Three croppers and three Negro women, who were wounded in this battle, were thrown into jail together with the others. An armed lynch mob is surrounding the jail supposedly to prevent a jail break and repel a rumored attack by the croppers, but—more likely—-to carry through a wholesale massacre of the prisoners. The lynch mob is scouring the country in search for the organizer of the Croppers Union and others of its leaders, using blood-hounds and they are armed to the teeth. The Negro huts throughout the area are deserted.

The skirmishes started Wednesday night when deputies attempted to break up a mass meeting called by the Croppers Union to protest the Scottsboro legal lynching and draw up demands for food from the landowners. Despite the landlord’s terror another meeting was held at Dadesville, county seat, on Thursday night, with over 500 croppers attending.

The southern newspapers are playing up the struggle as a struggle between the Negroes and whites. The Birmingham Age-Herald has a scream headline “Armed Negro Red Threat Heard.” Saturday morning’s Chattanooga Times, under the headline “Alabama Posse Moving Toward Red Gathering” reports that an army of 600 white mobsmen are moving on another meeting of 500 Negro croppers to “settle the racial difficulty.”

The struggle of the Negro croppers is for bread and against death from starvation. On July 1st all the food allowances granted the croppers by the landowners were cut out. The only means of sustenance for the croppers and tenants was the meagre allowance of fatback, corn and flour–ranging from one dollar’s to two dollars’ worth a week for an entire family—advanced by the landowners. By July 1 the crops had been “put by”—planted and plowed—and by cutting off the allowances the landlords served notice on the croppers—Negro and white alike—that now they had the choice of starving on the land while the crops they put by were maturing, or starving elsewhere. It was an effort by the landowners to drive the croppers off the land and take their entire crops when harvesting time came Then they could employ day labor at 50 and 25 cents a day. The croppers have nowhere to turn for food. They haven’t got a red cent.

The Croppers Union, which first began organizing here about two months ago. rapidly grew to take in croppers from practically every farm and plantation in Tallapoosa County and some in Lee County. Their prime demands are the continuation of the allowances until harvest and settlement at that time with the landowner.

The meetings broken up by the deputies and the landowners were probably mobilization meetings for mass demonstrations at the county seat for relief and for the continuation of the allowances. This cry for bread is being met with an army of terror.

Following the cutting off of the allowances the landlords offered some of the croppers the alternative of working on their truck patches at 50 and 25 cents a day, or at the sawmills at $1 a day. They put many of “their” croppers to work on the county roads and in the Whiteman’s cemetery to pay off the landlord’s road and school taxes which are $5 each.

A white worker from Camp Hill writes the following to the SOUTHERN WORKER, just a day before the fighting began: “The white bosses of this place has got a gang of Negro boys and men working in the white boss cemetery to pay their taxes. They don’t have anything to eat and have three bosses over them seeing that they don’t get any rest until 12:30. Then they only give them 30 minutes to try to find something to eat. By a white worker who is looking after the condition of the work class because he knows he will soon be treated the same way. We workers must get together.”

Another white tenant farmer from Camp Hill, who together with his family of five lives on $1 a week which his daughter makes cooking out, writes at the same time: “Wake up Croppers Union, let us get together.”

While in this section there are but few white croppers and poor farmers, they seem to be taking sides with the Negro croppers. They may yet be heard from at any time, giving their active support to the struggle of the Negro toilers for their lives.

The Scottsboro legal lynching plays a prominent part in the struggle. The fight of these croppers of Tallapoosa for food becomes immediately a fight against the whole system of national oppression against the Negroes in the South. In an area where four Negroes speaking together make a “dangerous crowd”, the significance of mass meetings of 500 as a mass defiance of the lynch law system can readily be understood. To the starving croppers of Tallapoosa, Scottsboro had become a symbol of the whole system of oppression and persecution to which they are subjected. The fight for food had broadened out almost automatically into a struggle against white ruling class tyranny

This struggle is but the beginning. Similar conditions prevail throughout the Black Belt, where between seven and eight million Negro croppers, tenants and poor farmers form the majority of the population. The meagre advances are being cut off, wages for day labor have fallen as low as 15 cents a day in some sections of South Carolina. The misery of the mass starvation on the farmlands is bringing things to a breaking point. Bigger and bloodier struggles are predicted before the summer is over. For these courageous croppers struggling against starvation and tyranny there must be the broadest possible support from the masses of Negro and white workers throughout the country. The Tallapoosa croppers have made “Scottsboro” the rallying point for a deeper and more basic struggle against the domination of the white ruling class.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1931/v08-n175-NY-jul-22-1931-DW-LOC.pdf