For the first issue of Partisan Review a look at four magazines of proletarian literature, Left Front of the John Reed Clubs, Jack Conroy’s midwestern The Anvil, and New York City’s Blast devoted to short stories and its Dynamo to poetry. I believe Waldo Tell to be a pseudonym for Edwin Rolfe.

‘Four New Journals of Revolutionary Writing’ by Waldo Tell from Partisan Review. Vol. 1 No. 1. February-March, 1934.

Left Front, Revolutionary Art of the Midwest. Organ of the John Reed Clubs of the middle west, published bi-monthly at 1475 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago, Illinois. Edited by Bill Jordan. Volume 1, Number 3. 10 cents.

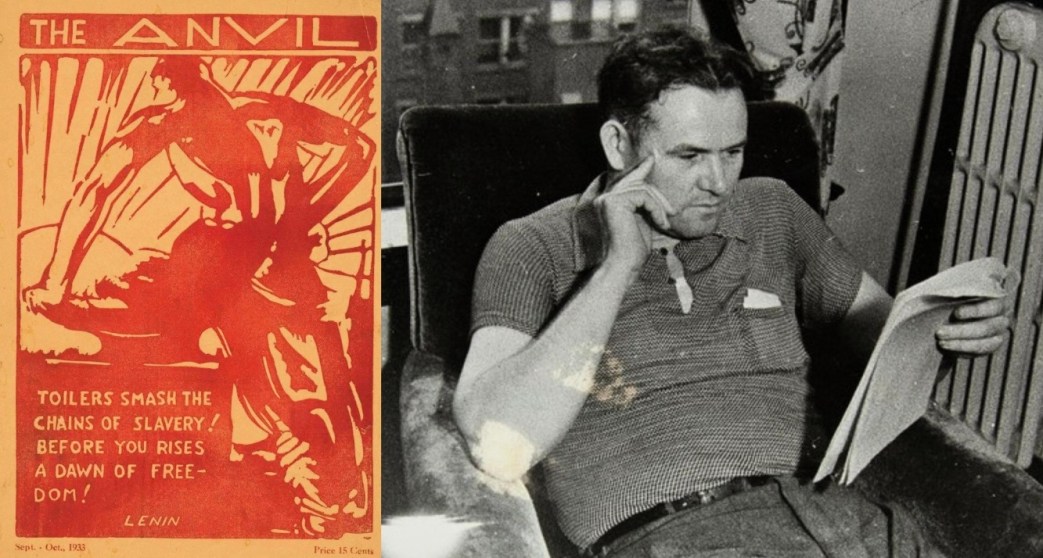

The Anvil, Stories for Workers. Edited by Jack Conroy in Moberly, Missouri. Volume 1, Number 4. 15 cents.

Blast, Proletarian Short Stories. Edited by Fred R. Miller in New York City. Volume 1, Number 3. 20 cents.

Dynamo, A Journal of Revolutionary Poetry, edited by S. Funaroff, Herman Spector, Joseph Vogel and Nicholas Wirth, New York City. Volume 1, Number 1. 15 cents.

HERE ARE FOUR little magazines, all of them recent arrivals on the American literary scene, which prove—despite the sneers and sarcasm of the literary liberals—the growing vitality of revolutionary writing in America. All of them are slim—they range in size from 16 to 32 pages— but within their limited space appear more advanced contributions to revolutionary fiction and poetry than have appeared in any American magazine for a long time.

Left Front claims the real distinction of being the first of the sectional John Reed Club magazines, which now includes The Partisan (Hollywood), Red Pen (Philadelphia) and Partisan Review. Its primary appearance in the field has enabled its editors to progress from the publication of an imitative, pseudo-modern format to the striking professional appearance which Left Front presents today. Moreover, in addition to this decided advance, the editors of Left Front apparently have resolved the status and character of their publication. It is exactly what its subtitle claims for it: the organ of the John Reed Clubs of the Middle West. In its twenty large pages can be found such excellent documentary articles as Edith Margo’s The South Side Sees Red, a praiseworthy examination of the awakening to militant class struggle of the great Negro population of Chicago; such competent stories as J.S. Balch’s A Drink of Water and Tom Butler’s The Strike Comes to Thorne Run; noteworthy reportage on the midwestern farm struggles by Ben Field and Obed Brooks, and book reviews by Joseph Kalar, Orrick Johns, Bill Jordan, Jack Conroy and others. The poetry does not approach the standards set by the other departments, although Prelude is the most promising poem by William Pillin that I have seen. And since it is the prelude to a longer series of poems entitled North America one hopes for greater poetic achievement from Pillin’s pen. Henry George Weiss’s Negro Ditch Digger is impressionistic verse, distinguished neither in technique nor in meaning. Richard Wright’s Rest for the Weary and A Red Love Note reveal genuine feeling and potential power, but they are manifestos to the ruling class, affirmations of class-power and self-identification by the author (a young Negro poet) with the working class; they are not poetry.

The Anvil, edited from Moberly, Missouri by that most indefatigable of revolutionary literary editors, Jack Conroy, is a magazine composed solely of short stories and verse. Its function is simpler than that of Left Front, since it is purely an outlet for creative revolutionary literary expression, with no ties to any closely-knit organization such as the John Reed Club. The January-February number contains stories by Samuel Gaspar, John C. Rogers, J.S. Balch, Alfred Morang and two newcomers: Harriet Hassell and Robert O. Erisman. Of all the stories, Alfred Morang’s Death in the Rain and Balch’s Telephone Call impress me most. Morang, particularly deserves close attention; his growth within the past year has been steady and certain, and he is gradually eliminating some of the immaturities which marred his earlier stories. The verse in The Anvil is painfully sincere but, with the exception of two poems by Walter Snow and Edwin Rolfe, of little value as poetry.

Three unusual stories appear in the third number of Blast edited in New York City by Fred R. Miller. W.C. Williams’ The Dawn of Another Day is an erratic, unclear, but nevertheless significant story about a penniless young man, one of the middle class ruined by the crisis, who realizes his new class position in society through a sensuous-mystical contact with a woman of the working class, a Negro woman. The story is pictorially effective, and makes use of conversation in a manner which very few American writers, least of all revolutionary writers, have mastered. But the disparity between the satisfying prose and the amorphous, unclear ideological approach makes this story a failure, if we are to take Blast’s subtitle, “proletarian short stories” seriously. Because of the unresolved nature of his approach, Williams uses the figures of the Negro woman as the symbol of uprooted identity with reality. D.H. Lawrence attempted a similar semi-personal, semi-mystical identity with reality, and failed. Even though to Williams the reality of woman symbolizes class consciousness, the connection is far too tenuous and personal to hold meaning for the reader.

Richard Bransten has something of the same respect for sensuous detail that Williams possesses. The use of it in his story Misdeal partly redeems the stereotyped situation with which he deals—that of a young man who, losing his job, is forced into the growing mass of workers who begin to question the very basis of capitalist society. But the occasional vigor and fine observation of the earlier parts of the story are lost sight of in the trite culmination of the tale.

Alfred Morang’s contribution to this issue of Blast is a short and slight but well-integrated short story, Free Slaves. One other story should be listed here, Hackman by Harry Kermit, a competent narrative the imaginative meagreness of which is redeemed by excellent reportorial detail.

The first issue of Dynamo, a journal of revolutionary poetry justifies the long period of its preparation, during which many of its well-wishers thought it had met a pre-natal end. It is the smallest of all the magazines we have discussed, and at the same time the most mature, sober, unpretentious. Not only have its editors collected in its 24 small pages some extremely significant literary contributions; they have also, as these very contributions reveal, set a high standard of literary merit which is sorely needed in revolutionary literature. It is a standard which proves that revolutionary literature—or, more precisely, in the case of Dynamo, revolutionary poetry—has definitely passed its hit-and-miss, catch-as-catch-can period.

Haakon M. Chevalier, Horace Gregory, Michael Gold, Joseph Freeman, Isidor Schneider, Kenneth Fearing and Stanley Burnshaw contribute to this issue the best collection of revolutionary poetry which has appears since the publication of We Gather Strength. James T. Farrell, whose third novel, The Young Manhood of Studs Lonigan, is to appear this month, is represented with a short story, The Buddies.

It is unnecessary, I believe, to dwell long on the merits of the respective poems. All of them achieve a satisfying standard of poetic achievement. I should like here merely to examine briefly the six poems by Joseph Freeman and to recommend them for serious study both by poets and by readers of poetry—particularly the former group. Freeman, an excellent lyricist, offers in this group of poems an intensely personal series which at the same time varies and broadens our conception of what revolutionary poetry can be. While many poets who have been publishing their verse within the past five years have been content with what might be called revolutionary exhibitionism in verse, satisfied with the mere affirmation in their work of their identity with the working class or of their faith in Communism, Freeman has gone far beyond this. Although he has published very little during the past half-dozen years, his development as a poet, as his Six Poems written over a period of eight years reveal, use the acceptance of the class struggle—the goal for most of our poets—as a beginning; from this beginning, he progresses to a treatment of the limitless human problems—hope, doubt, anger, fear, pain—which have never before been adequately treated in revolutionary poetry. Instead of the grandiosely general, Freeman deals with the specific and achieves both by implication and direct statement more of the general meaning of the problems with which he deals than all of our younger poets.

This is not to say that Joseph Freeman is—at least in these poems—in accomplished poet. He still writes in the too-facile manner and forms of an outgrown method; his thought is too often dulled and blunted by convenient and traditional phrases. But his authentic poetic feeling emerges as the clearest and most honest statement of the revolutionary poet’s preoccupations that has as yet been published in this country.

Partisan Review began in New York City in 1934 as a ‘Bi-Monthly of Revolutionary Literature’ by the CP-sponsored John Reed Club of New York. Published and edited by Philip Rahv and William Phillips, in some ways PR was seen as an auxiliary and refutation of The New Masses. Focused on fiction and Marxist artistic and literary discussion, at the beginning Partisan Review attracted writers outside of the Communist Party, and its seeming independence brought into conflict with Party stalwarts like Mike Gold and Granville Hicks. In 1936 as part of its Popular Front, the Communist Party wound down the John Reed Clubs and launched the League of American Writers. The editors of PR editors Phillips and Rahv were unconvinced by the change, and the Party suspended publication from October 1936 until it was relaunched in December 1937. Soon, a new cast of editors and writers, including Dwight Macdonald and F. W. Dupee, James Burnham and Sidney Hook brought PR out of the Communist Party orbit entirely, while still maintaining a radical orientation, leading the CP to complain bitterly that their paper had been ‘stolen’ by ‘Trotskyites.’ By the end of the 1930s, with the Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939, the magazine, including old editors Rahv and Phillips, increasingly moved to an anti-Communist position. Anti-Communism becoming its main preoccupation after the war as it continued to move to the right until it became an asset of the CIA’s in the 1950s.

Access to full issue: https://archive.org/download/sim_partisan-review_february-march-1934_1_1/sim_partisan-review_february-march-1934_1_1.pdf