Wonderful reflections from Garlin providing a social snapshot of a time and a place as he remembers his Socialist youth in Glens Falls, New York (called Glendale here) centered on the story of assembling the Socialist Party band to parade on Armistice Day, 1918.

‘Queen City of the Adirondacks’ by Sender Garlin from Partisan Review. Vol. 1 No. 2. April-May, 1934.

MY FOLKS moved into that town in northern New York from Stonehill, on Lake Champlain, up in Vermont. We had come to Stonehill from New York City in 1906. A few months earlier, a bullet driven into my brother’s body during a pogrom in Bialystock, sped the family across the Atlantic. Shortly after our arrival my father found work in an East Side bakery.

My father liked best to lie on a couch and read; he found that work in the cellar-bakeries on Forsyth Street in New York’s East Side made him cough. That scared my mother, for two of his brothers had died of T.B. A friend told him of an “opportunity” up in Stonehill, Vermont, and so we traveled up there. It was a curious partnership with another man in which my father, mother and three brothers (the oldest was 12) worked to support the family of eight.

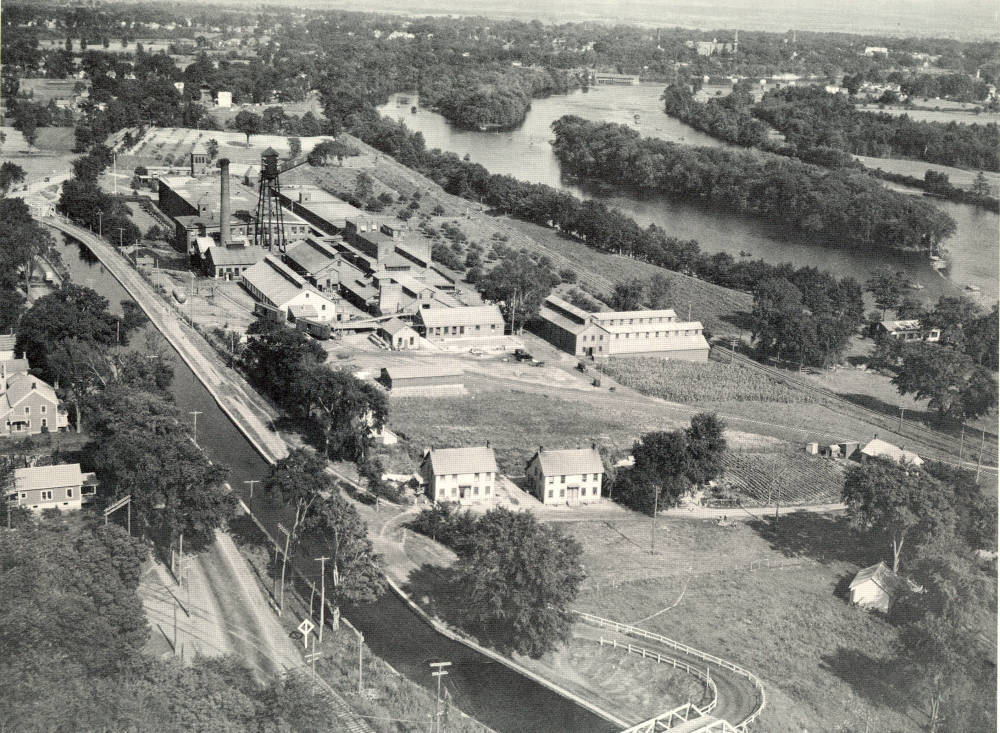

My folks left Stonehill in 1911 and came to Glendale where my father opened a bakeshop. Glendale, at the time, was a small industrial town in the Adirondack foothills. It was called the Queen City of the Adirondacks. It was a papermill town. During the spring months logs drifted down from the northern towns to be ground into pulp and then into paper by the workers of the International Paper Company in the gray-looking mills near the South Glendale bridge.

Only once did these workers get a half-holiday without having their pay cut. That was the day of the first Armistice celebration. The sirens in the three fire stations shrieked, the bells in the churches clanged, and everybody quit work and dashed out into the streets. We didn’t go to school that afternoon. I stood before the news bulletin in front of the office of the Glendale Times, reading the latest news of the “Armistice.”

The real Armistice didn’t come off until the following Monday morning, the 11th of November. I guess we expected it, because I arranged with Louie, who was a sound sleeper and the son of the tailor (who boasted that he once fitted up a custom-made suit for State Senator Emerson) to waken him when I heard the sirens screeching at the West Street Firehouse. Neither Louie, who lived opposite us, nor I had a watch or an alarm clock, so we worked out a system: he tied a string onto his toe and threw it out of the third-story window of his house. I’d waken him by yanking on the string, which hung from his window.

It must have been about four o’clock in the morning when the sirens announced the end of the World War. I dressed and went out to pull the string dangling near the porch.

Half the town was already on the streets. I thought it would be a good idea if Louie and I could be at the head of a parade, so I phoned the leader of the Socialist Party local, Dan Linehan (a lanky cigarmaker who called himself a manufacturer because he employed one helper) and asked him if it would be O.K. for me and Louie to take the big bass drum out of the headquarters and use it to start an Armistice Day parade. D.V., as we in the local called him, said he couldn’t see any “real objection” to it, provided we took good care of the bass drum, because “it was the property,” he said, of the Socialist Band.

The Glendale Times was owned by an influential citizen named Addison G. Colbert, who also owned the Glendale Trust Company. I never did find out whether it was true or not, but some folks in town said that when Addison G. Colbert was state treasurer under Gov. Richards, some money disappeared.

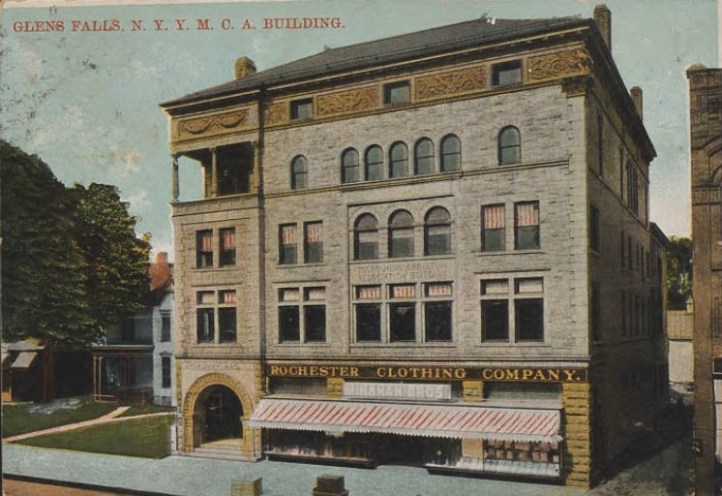

The Glendale Trust Company was the bank on Glen Street, right opposite the Y.M.C.A. It had those glass-topped tables with fine ballpointed pens where you filled out the deposit slips. This is the bank where my father got loans from time to time, provided he got some reliable business man to endorse a note for him. Once he got the lumber firm of Kendall & Green to endorse a promissory note for him so he could purchase lumber to build his bakery. After that, whenever my father saw Kendall on the street—even if Kendall was on the opposite side—he always doffed his cap and said, “Hello, Mr. Kendall and Green.” It seems my father didn’t realize it was the firm name.

Of course my father, who had read a good deal, knew that they were all a bunch of crooks, but he also knew they were powerful: they could decide whether to call in that “payable on demand” note of $100, so he always doffed his cap whenever he saw Mr. Kendall on the street.

The Socialist Band was quite a help to us in our work. The Prudential Insurance man, Gib Wendell, was the bandmaster. He didn’t charge to train the band because, Gib said, there was no reason on God’s green earth why anyone shouldn’t learn to play a musical instrument in a couple of months, especially if he agreed with our ideals.

Whenever August Claessens, Steve Mahoney or Mary McVicker came to town, the band assembled at the headquarters of the local and paraded to Monument Square where the open-air meeting was scheduled—all the time playing the “Albania,” a march with a real martial air. Sometimes as many as 75 or 100 followed us.

A lot of fellows around town even joined the Socialist local to get free lessons on the slide trombone or the cornet. A couple of fellows who worked at the Boston Confectionary experienced a sudden conversion to the cause, but as soon as they learned to play an E-flat clarinet they quit the party. Myself, I used to hold the bass drum while another comrade whacked on it. Gib Wendell promised that after a while I’d be promoted and get a chance to whack the drum, too.

But to come back to the Armistice Day parade. Louie and I went up to the Socialist local and carried the big bass drum down the steps. The headquarters were right above Fitzgerald’s Chop House; the hallways always smelled of stale beer and fried oysters. It was still dark, and as soon as Louie and I hauled the drum down, I started whacking it. After a while it looked as if we had the whole town following us, for everybody was excited about the war being over.

We marched thru the streets: past the Glendale Trust Company and the Y.M.C.A., down South Street; past the City Hall. Everybody in the line of march seemed eager to follow our leadership. Suddenly we discovered that the people behind Louie and me had dropped out of the parade, then the folks right behind them, until after a while only Louie and I were celebrating the Armistice.

While it was still dark, the parade stretched behind us, but as it grew light the townspeople dropped out when they saw on the bass drum the words: Workers of the world unite! You have nothing to lose but your chains!

After the band escorted two or three out-of-town speakers to Monument Square at different times, we in the local became conscious of our rights as citizens in the community and taxpayers in the town. We elected a committee headed by D.V. Linehan to call upon the Common Council at the City Hall. The local wanted us to take up the question of getting a share of the 12 summer concerts for our own Socialist band. The contracts for these concerts usually alternated between the Glendale Band and the Elks Band. The musicians in these bands were dressed in natty blue uniforms, with golden whirlgigs on their coatsleeves; and they liked that. During the day some of them worked in Robinson’s Hardware Store or Joubert’s barbershop, and it felt good to have your friends see you in uniforms.

The Common Council listened to our delegations because most of them were known in town to be men of sobriety who always paid their debts; several of the Socialists were even members of the Odd Fellows or Modern Woodmen of America. Before we left the City Hall we received the assurance of the Common Council that the Socialist Band would get four out of the regular twelve concerts scheduled for the summer. These concerts were given in the City Hall Park, and we’d always know the concert was on when we heard in the distance the strains of the “Star Spangled Banner,” and we knew it was over when they played “Home Sweet Home.”

When we forced the Common Council to give our Socialist band four of those Concerts, the folks in the local thought it proved what could be done when people stood up on their hind legs and demanded their rights as citizens. But when summer came we were in a jam, because our Socialist band could play only the “Albania.” Gib Wendell, our bandmaster, had to hire the men in the Elks Band to play for us.

The folks in the local thought it was a step forward, anyhow, because Gib arranged for the Elks musician to wear the uniforms used by the members of the Socialist band. There was an arm and torch sewn on every one of those uniforms and Linehan, the cigar “manufacturer,” thought it was a darn good way of putting our message over on the Henry Dubbs.

Linehan was tall and lean, and he always reminded me of Gene Debs. I heard Debs for the first time when I was about ten years old. He was on a nationwide lecture tour, and lots of people came to the county courthouse to hear him. There was no admission charge, but you had to buy a subscription to Debs’ magazine, the Rip-Saw, to get in. It seemed to me that he bent his tall, lean body way over, as if he wanted every word to get right into the hearts of those listening to him. His speech was very eloquent—like those of Wendell Phillips that I had read. Debs began his speech by saying that “as the petals of a flower open up under the beneficent rays of the sun, so my heart opens up to you, my dear friends.”

We didn’t have many mill workers in our local in Glendale. Many of the members also belonged to the Workmen’s Circle, and some of them owned small dry-goods stores and grocery stores, but most of them were junk peddlers. A few of the well-to-do members had started business as pack peddlers. They used to travel by horse and wagon through the mountain towns of the Adirondacks. They sold cheap suits, sleazy dresses and paper-bottomed shoes to the goyim, and brought back skunk-furs which they sent down to Albany at a neat profit. When their sons graduated from high school, the fathers sent them to Union College in Schenectady—or, as one of the more prosperous skunk-dealers did—even to Harvard. Later the boys came home for vacation, and stood in front of the Y.M.C.A. on Glen Street, wearing their letters on their athletic sweaters, and eyeing, with a superior air, the high school seniors as they passed.

The junk peddlers couldn’t make very much buying and selling waste paper, rubber and tin. Many of them were former sweatshop workers who had come to town with the consumptive flush already on their cheeks. They became junk peddlers even though they didn’t have a cent to their name. The richer Jews who owned the junk shops advanced the sixty or seventy dollars needed to buy a spavined horse, a wagon and a set of harness; the newly-established junk peddler was, in turn, obliged to sell all the junk he collected to the junk dealer who had provided the horse and wagon.

Through a sort of a share-cropping system, the junk dealer got a fancy rate of compound interest on his investment. He never pressed the peddler for the original outlay. In this way he had a permanent claim on him.

When I was about 14, just about the time I became active in the Glendale Socialist local—and about the time the Socialists elected George R. Lunn as mayor of Schenectady, the General Electric town about 43 miles distance—just about this time I developed a hankering to be a fireman. Not that I yearned to get up out of a warm bed in zero weather to put out fires, but because I felt that if I were a fireman I’d have lots of time to read all those books and pamphlets which the fellows in the local were always talking about; those exciting books by Upton Sinclair; Kirkpatrick’s War, What For?; Buchanan’s The Story of a Labor Agitator; Debs’ Life, Letters and Speeches, and all the vibrant copies of the Appeal To Reason, the Rip-Saw, and the illustrated International Socialist Review.

There were many fires in Glendale during the winter months. The fires always broke out shortly after midnight. One Friday night, my father took the whole family to the Empire Palace to see a movie about the murder trial of Police Lieut. Charles Becker, Lefty Louie, Dago Frank, and the other gangsters who were mixed up in the murder of the gambler, Rosenthal. A few minutes after we got home we heard two long whistles and four short ones, and my father said casually, “Well, there goes Stein’s store.” Of course my father had no advance information about the fire, but I guess he knew that Stein’s business was on the blink.

The Post-Star next morning told about the damage caused by the blaze, reported that the place and the merchandise were “partly covered by insurance,” and explained that the fire was of “unknown origin” or that it was caused by “spontaneous combustion.” Some smiled cynically, but most of the decent citizens, and especially the business men, didn’t say much because they were glad that a little more money was coming into the community from the outside.

Of course the people whose place burned down put on long faces before the neighbors, and wept about the awful calamity that had befallen them. But most everybody recognized this as a necessary ritual.

That winter one or two of the insurance companies threatened to cancel the policies in certain sections of Glendale unless these fires of “unknown origin” and “spontaneous combustion” stopped. On the whole, however, this activity was recognized as part of the legitimate business enterprise of the community.

So my boyhood passed in the Queen City of the Adirondacks. Every winter there were fires, and when a celebrity came to town the Socialist Band played the “Albania” march. The Socialist local dozed placidly through the years. When the papermill workers went out on strike the Socialists could not understand.

Partisan Review began in New York City in 1934 as a ‘Bi-Monthly of Revolutionary Literature’ by the CP-sponsored John Reed Club of New York. Published and edited by Philip Rahv and William Phillips, in some ways PR was seen as an auxiliary and refutation of The New Masses. Focused on fiction and Marxist artistic and literary discussion, at the beginning Partisan Review attracted writers outside of the Communist Party, and its seeming independence brought into conflict with Party stalwarts like Mike Gold and Granville Hicks. In 1936 as part of its Popular Front, the Communist Party wound down the John Reed Clubs and launched the League of American Writers. The editors of PR editors Phillips and Rahv were unconvinced by the change, and the Party suspended publication from October 1936 until it was relaunched in December 1937. Soon, a new cast of editors and writers, including Dwight Macdonald and F. W. Dupee, James Burnham and Sidney Hook brought PR out of the Communist Party orbit entirely, while still maintaining a radical orientation, leading the CP to complain bitterly that their paper had been ‘stolen’ by ‘Trotskyites.’ By the end of the 1930s, with the Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939, the magazine, including old editors Rahv and Phillips, increasingly moved to an anti-Communist position. Anti-Communism becoming its main preoccupation after the war as it continued to move to the right until it became an asset of the CIA’s in the 1950s.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/sim_partisan-review_april-may-1934_1_2/sim_partisan-review_april-may-1934_1_2.pdf