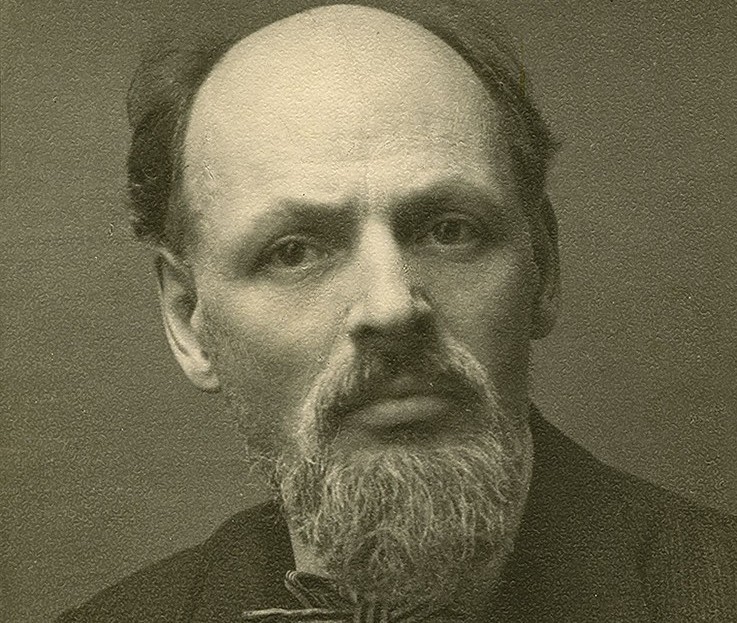

A central figure in the founding of French Communism, former syndicalist and Socialist leader Amédée Dunois, on the Party’s leadership and its Left, reports on the crisis in the Party over the Right’s victory at the 1922’s Marseilles Congress and the subsequent victory of the Left at January, 1923’s national gathering. Dunois himself would lose his positions in 1925 and later be expelled as an Oppositionist in 1927. Rejoining the SFIO in 1930. Arrested by the Nazis for his partisan anti-fascist activity in 1943, Dunois died in Bergen-Belsen in 1945.

‘The Situation in the French Communist Party’ by Amédée Dunois from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 3 No. 15. February 13, 1923.

Is the Communist International now at the end of its trials in France? Many of us who did not even venture to think this eight days ago, now venture to hope it. To be sure the crisis still continues, but it has already lost much of its violence. And it is above all a good sign for the convalescence of the party that Frossard’s secession, instead of sharpening the internal disturbances, has by no means caused the confusion which our enemies had hoped for.

The crisis continues. But who could have believed that the decisions of the 4. world congress, relating to the French question, would cause so little resistance or schism in the party itself? From what we know of our centrists–I am not speaking of the masses, but only of the leaders–it is a very good thing that their counter-mines were not more powerful, and that it took so long before they exploded.

The crisis is not of recent origin. If we wanted to write its history, we should have to go back to the period immediately following the 3. world congress. Indeed, a thorough investigation into its causes would oblige us to look even further back into the past, to the party conference at Tours. Our research would show us the following: First, that the two tendencies which united at Tours against reformism have never become so completely fused with one another as to lose their distinguishing characteristics, and secondly, that the elements composing the committee of the 3. International, originally forming the party Left, were far too lacking in homogeneity not to be condemned to divisions within a very short time.

The crisis came to an outbreak at the party conference at Marseilles at the end of December 1921. This outbreak was distinguished by three facts:

1. The non-election of comrade Souvarine to the new Executive Committee, this following on a violent campaign ostensibly carried on against him personally, but in reality against the ideas represented by him, the ideas of the International itself.

2. The election to leadership of a number of persons who were communists only in name, and who have since withdrawn from the party, either voluntarily or on compulsion: Barabaut, Verfeuil, Jules Blanc, Ferdinand Faure, Pioch, Brodel, etc.

3. The immediate resignation from office of four of the newly elected executive members: Loriot, Treint, Vaillant-Couturier, and Dunois, as a protest against the election methods which had been employed, and as a protest against the out-voting of Souvarine and against the offensive return of the party Right.

From this time onwards there was war within the party. The party factions were revived. On the one side the Left, which (in its best elements at least) incorporated the true spirit of the International, and placed the International before everything else. On the other side the elements of the Right, the Centrists, the hyper-radicals, and the councillors of confusion, in short, all those who inclined, more of less openly, to setting up the party in opposition to the International, as if it were possible to compose a fraction to the whole, and to divide the indivisible!

The main fight was fought around the question of the United Front. While the Left from the very first accepted the tactics proposed by the International, the right, centre and extreme left rejected these tactics decisively, and attempted to make them appear ridiculous in the eyes of the workers. The Executive of the C.I., which followed the course of the conflict with anxious attention, speedily recognized that this antagonism to the united front, in the case of the majority of its leaders, concealed a growing antagonism to the International itself.

Twice the International tried to adjust the crisis along peaceful lines, for it feared the effects. Already in February some of the representatives of the majority were invited to

Moscow, for the purpose of discussing in detail with the International the organizatory and tactical questions dividing them from the left. The representatives of the majority went to Moscow, and there undertook to submit to the resolutions passed. But unfortunately their actions were not in accordance with their promises, so that the crisis was not cured, but became acuter than ever.

Immediate action was necessary. The first was the expulsion of Henri Fabre, the second the summoning of Frossard to Moscow. In the course of a renewed session of the Enlarged Executive, in June, the French question was thoroughly debated in a plenary sitting, and a long resolution finally passed, and signed by Frossard. This resolution contained the well known slogan which would have put an end to the crisis. This parole consisted of the union of the party centre with the left, against the right.

At this time we were justified in hoping that everything would now fall into its proper course, and that the union of centre and left for the welfare of the party would become actual fact.

But nothing of all this occurred. Frossard, who possesses a clear head but an easily affected heart, a keen understanding, but a weak will, declared at first that he would be no French Serrati. But who can build on Frossard’s words? Three months later he had no other object in life than evasion and denial of his promises. Has Frossard really been a second Serrati? Not at all, he has merely been a second Levi! Frossard has undoubtedly been the most guilty of the leaders of the party executive, the greatest culprit of all. The failure of the Paris party conference in October was desired, thought out and contrived by him, was solely his fault that this party conference went to pieces, after four days of dreary debates, with an open breach between the two main factions, whose union would have saved the whole situation. This was his fault alone, for he neither organized nor led the conference, but left it to anarchy.

But was this break with the left anything else, for the party centre, than the break with the International it already intended?

Much could be said on this sorry episode. The task is much facilitated by the judgment pronounced on the October party conference, first by the delegates of the International and then by the International itself. It is the centre, the centre alone, which is “responsible for the breach which has occurred”. It is true that the centre quitted the party conference as material victor, and took over the sole leadership of the party, but morally it left the conference as the vanquished, for it left it discredited.

To us it was perfectly clear that in the centre, and especially among its leaders, there were many who actually desired a breach with the International, who had not submitted to the most moderate decision of the delegates of the Executive in the party committee, and would just as little submit to the supreme decision of the International itself at the world congress.

The resignation from office of a number of editors of the Humanité, and of some party functionaries, appeared regrettable to many comrades at the time; as perhaps did also many of the publications of the Bulletin Communiste. But both proceedings were fully justified in view of the existing urgent and serious danger arising for the party from the breach of faith of the centrist leaders. It was necessary to strike quickly and energetically. And this the left did, even at the risk of not being immediately understood by the masses.

Thus six weeks passed. While the world conference was holding its sessions in Moscow, in Paris the struggle against the split in the party was being organized. For what could be the ultimate result of the rebellion against the International if not a split? The left, led by a committee of seven which held consultations almost daily, increased its announcements, corrections, warnings, proclamations, and appeals. It presently published a weekly periodical for purposes of fighting and information, the Cahiers Communistes (Communist Pamphlets). It caused resolutions to be passed all over the country, expressing unqualified fidelity to the III. International. The party centre appeared to regard this lively public activity of the left with perfect passivity; it seemed as if the centre had ceased to exist.

But the centre had its plan. At the moment the centre was composed of Frossard alone, for Cachin, Ker, and Renault, were in Moscow. And Frossard had a plan, well thought out and prepared. This consisted of having the resolutions of the 4. world congress, of whatever nature, rejected by the party leadership as “dangerous and impracticable”, summoning the French party to resistance against the International. Frossard was well aware that in France, nationalist feelings are never appealed to in vain. To be sure the left would rage, protest, and threaten. But that would not matter much. The left could be condemned to impotence, by being deprived of all inner and outer means of propaganda and expression, or, if necessary, by being expelled from the party. And as regards Moscow–the centre was prepared to meet action from this side with perfect calmness! Moscow would certainly suspend the French section. And this was precisely what Frossard wanted: He wanted to regain his own freedom of action, and then later, when he had his own party and his own newspaper, and felt himself sufficiently powerful, he would “re-enter” the International on his own terms, not on those of the International. Frossard actually cherished the fantastic dream of one day imposing his own conditions on the International! The confidential friends of the clever General Secretary of the Party had been long familiar with these plans.

But even the most carefully prepared intrigues do not always succeed, and that conceived by Frossard was destined to a miserable collapse. The affiliation of the C.G.T.U. (Unitarian General Labor Confederation) to the Red International of Labor Unions was a severe and bitter disappointment to Frossard and his followers. The Humanité devoted merely a few obscure lines on its third page to this event which was of so great importance to the labor movement! The extreme moderation of the 4. world congress was also a great disappointment to our conspirators, who had certainly not expected so much consideration and forbearance.

At this moment Frossard wrote a strange and disquieting article, in which he reserved to himself the right of complete liberty of action with regard to the award of the International the right of saying yes or no, of submitting or defying, and this although he himself had applied for the award to be given.

In the Humanité, and in the party, the campaign of schism was energetically carried on. For a whole week, from December 9. till 16. everything was hanging fire.

But despite this the rupture was not accomplished. At the last moment Frossard thought better of it and submitted. He had not only the left against him, but even the masses of the party centre, who are faithful followers of the International and the Russian revolution. The powerful opposition of Louis Sellier, Cachin, Ker, and Renault, all leaders of the centre, completely crushed his intrigues. In the party sitting of December 16. Frossard was the first to sign the agenda submitted by Sellier, expressing unconditional recognition of the decisions of the 4. world congress. This saved the unity of the party. The danger of a rupture again vanished abruptly.

All that remained to be done was to carry out the resolutions passed. While Frossard prepared for the journey to Moscow, where he was to take up his position as delegate to the Executive, the party executive adopted measures for the immediate execution of the decisions relating to the resignation of the communists from the free-masonic lodges and the League for Human Rights. The editors who had resigned from the Humanité were re-instated. But this re-instatement involved dismissals, which were arranged for by a commission especially appointed for the purpose. This commission selected for dismissal, in the first place, those editors of the leading newspaper who had most contributed to the split adventure. The editors thus discharged set up a deafening uproar of recriminations, which was benevolently echoed in the bourgeois and reformist press. Indeed, they did even more. They uttered such violent threats against Frossard, their accomplice and clique-leader of yesterday, that he saw no other way of escape but to resign from the party: “The fox was caught in the trap!” This is the state of affairs at present. The “refractory” elements have founded a so-called “Communist Defence Committee”, which is trying to gather together all oppositional elements, all the weak spirits, the seekers for vengeance, would-be politicians and legal tricksters. In a few days this committee will have its own newspaper, the Egalité (Equality), which is to be the organ of an alleged united communist party, which party must however be first founded. We have nothing to fear from either this newspaper or this party, and merely look quietly on at the impotent agitation of a group whose credit is already exhausted.

Under the leadership of Louis Sellier, the party central has energetically combatted these despicable intrigues. The unruly elements who most compromised the party have been expelled, the rest have been appealed to cease to support the instigators. At the same moment the persecutions of the Communist Party and the C.G.T.U. set in. About ten comrades were thrown into prison. House searches were made in the Humanité. As these arbitrary measures do not happen spontaneously, but have been long expected, every single worker will be able to recognize without any difficulty that Frossard, Pioch, Torres, etc., have only left the party in order to place their valuable persons in safety before it was too late. Discretion always has been the better part of valour!

The sitting of the National Council (central committee), which was held recently, will vanquish those enemies of the International who had insinuated themselves into the party. It will clear the party of the unsound and dishonest elements which have tried to lead it on the wrong path. It will complete the work began at Tours. It will correct the errors and mistakes of the party conference of Marseilles, and wipe out the last traces of the Paris party conference.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1923/v03n15-feb-13-1923-Inprecor-yxr.pdf