An absolutely fascinating study from Valerian Ossinsky, a Deputy People’s Commissar for Agriculture, of the character and changes of capitalist agriculture in the U.S. after World War One. Valerian Ossinsky (Obolensky) was a leading early Soviet economist and Left Communist, later ‘Democratic Centralist,’ in the years after the Revolution. One of the signatories of the The Platform of the 46, he was a lead voice of the Opposition on economic matters in the debates of 1923-1924. Like a number of Oppositionists, Ossisnsky was moved to the diplomatic corp, becoming ambassador to Sweden. Breaking with the Opposition in 1925, he was elected to the Central Committee with much of his work with Gosplan and in agricultural planning. He aligned himself with Bukharin in the collectivization debate, but retained his membership in the Party, with academic work largely replacing Party and state activities. Arrested in October, 1937 during the Purges, Ossinsky was a witness in the trial of Bukharin and Rykov and executed on September 1, 1938.

‘Agrarian Relations in the United States’ by Valerian Ossinsky from Workers Monthly. Vol. 5 Nos. 9 & 10. July & August, 1926.

N. OSSINSKY, former Commissar of Agriculture in the Russian Soviet Republic, is one of the most prominent agronomists in the world. The investigations, some of the results of which this article presents in a very sketchy fashion, were undertaken during a special trip of several months duration throughout the United States. The complete reports of the investigation are recorded in the Russian journal “The Agrarian Front” and in the international scientific organ “Unter dem Banner des Marxismus.” The following is but a sketchy condensation of the wealth of material contained in the full reports.

THE purpose of the following investigation is to throw light upon the tendencies of American agrarian economy. Economists have a habit of representing the United States as the classic land of the so-called “labor principle”—that is, a land where the owner of the land also works it and where the capitalist principles of the concentration of property and exploitation cannot be found to any large extent in agriculture. The following conclusions, based upon official sources, especially the material of the 1920 census and the publications of the department of agriculture, will show in how far such pretensions are justified.

1. Who Possesses the Land of the United States?

The entire territory of the United States extends over 1,903 million acres. If we subtract the 122 million acres upon which cultivation is impossible (deserts, swamps, soil under cities, etc.), we have 1,781 million acres used for agricultural purposes (including cattle raising.)

In 1919 this 1,781 million acres belonged to the following categories—farmers, private non-farming enterprises, federal government institutions, other state and social institutions—in the proportions shown in Table I.

From this table it follows immediately that 26.4% of the entire land belongs to private non-farming enterprises, 20.5% to the federal and state governments and other social institutions, and no more than 53.1%—that is, somewhat more than half—could be found in the hands of farmers. As we shall see below 20.9% (374 out of 1,781 million acres) of the entire land is in the hands of tenants. This means that the farmers working their own land possess, in the United States, no more than 32.2% of the entire agricultural area.

In other words, less than one-third of the land belongs to farmer-owners—large, middle, and small. One-fifth of the land belong to farm tenants. The other half belongs to owners who do not themselves cultivate the soil but hire out or operate it through wage labor.

It is significant to note the distribution of the forests. Less than one-third belongs to farmers—more than one-fifth belongs to the government. The other half (47.2%) belongs to private companies.

Grazing land in the dry regions of the West belongs to farmers to the extent of hardly 28%: to the government, about 48%. (This constitutes the only land in America now used for colonization purposes). Thirty percent belongs to the rail roads, to the great cattle companies, and to private enterprises in general. These private enterprises own 30% of the grazing land in the better well irrigated regions.

2. The Size of the Farms.

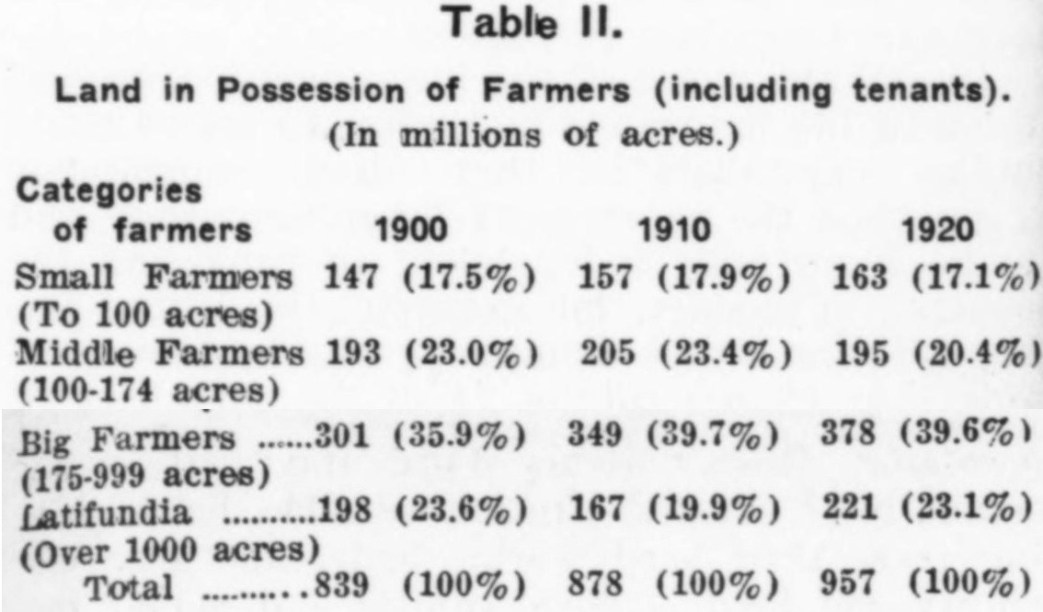

According to the above it appears that in 1919 the farmers as a whole (including tenants) owned 946 million acres of 53.1% of the entire agricultural area of the United States. How is this land—divided among the big, middle, and small farmers and what are the tendencies of development of these categories between the year 1910 and 1920. Let us examine Table II.

What do we learn from this table?

1. In 1920 the great estates made up 63% (39.6% plus 23.1%) of the entire agricultural territory. Surely these enormous farms were not built up on the “labor-principle.” Moreover, it must be remembered that among the smaller farms (less than 175 acres) there are many capitalist enterprises (dairy farms, vegetable farms, orchards, etc.)

2. Between 1900 and 1910 capitalist farms declined. (In the South the great plantations were divided up, leased or sold). Between 1910 and 1920, however, the development was again strongly upwards.

3. Conservatively estimated, 40% of the farm land belongs to strongly capitalistic enterprises. About 25% belongs to very great farmers, 20% more to middle farmers, and 15% to small farmers. The small farmers, however, own over a half of the number of farms in the country.

3. Owners and Tenants.

Let us now consider the nature of the land cultivator. Here we have essentially three categories: full owners, part owners, and tenants. The full owner works his own farm; the part owner owns land but he hires more land to be able to extend his economy; the tenant owns no land at all. The relations of these three categories are expressed in Table III.

From the figures it appears that the possession of the full owners grew very slowly (indeed between 1910 and 1920 there was a diminution of 4,000,000 acres). At the same time, however, the lands of the part owners and tenants grew continually and quickly—for the first category an increase of 42,000,000 acres, for the second of 44,000,000 acres for the period between 1910 and 1920. This increase was not at the expense of the land formerly operated by full owners but took place through expansion to lands hitherto uncultivated. In other words, the entire increase in cultivated land in the ten years went to part owners and full tenants.

According to the structure of the economy we can regard the full owner as the “typical” average farmer although the figures for this category hide a great many capitalist enterprises. The part owners are mostly big enterprisers who utilize the momentary state of the world market for the extension of the cultivation of certain grains and hire the needed additional land for that purpose. The full tenant is on the average a small farmer who works a portion of the time for the land owner in the form of rent payment. It therefore appears that the element that can in any way be associated with the “labor-principle” possesses no more than a quarter (48% of 53.1%) of the entire agricultural territory. The rest of the land is cultivated on something very different from the “labor-principle.” If now we recall that among the full owners there are many big capitalists the number of “working farmers” who own their own land in America is very small indeed.

A word or two about the tenants. Not all of them, of course, are small landowners. According to the 1920 figures it appears that 49.2% of all rented farms were found in the hands of tenants renting but one farm; 50.8% in the hands of those renting more than one farm, 25.4% of the farms in the hands of those renting five or more farms. The farmers of this last category can hardly be called “working farmers;” they are in truth capitalist enterprisers.

4. Land as a Commodity.

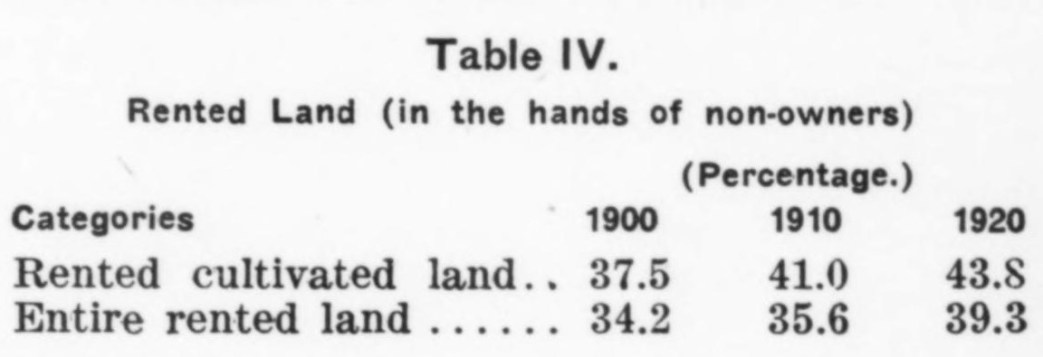

We have seen that in 1920, 27.7% of the total agricultural territory was found in the hands of full tenants. From this alone it follows that a great part of the land in America is passing from hand to hand. But this is not all. We have seen that there is a great number of partial landowners who are also partial tenants. If we add the rented land of the full tenants to the rented land of the partial tenants we get as follows:

In 1920, therefore, the proportion of rented land reached almost 40% (39.3%). And, if we consider not land in general but land actually cultivated (and this is the point), we reach the conclusion that about 44% of the entire agricultural area is cultivated by persons who are not owners of the land. As a matter of fact the figures are higher. Of course they do not reach the English level where, in 1914, 90.2% of the agricultural area was in the hands of tenants. But they practically reach the Belgian level (54.2% in 1910); they are higher than in Ireland (36% in 1910), or in Germany (12.7% in 1907.) Apparently land is a very mobile affair in the United States.

These figures in themselves, however, do not tell the whole tale. It is necessary to find out how frequently the tenant changes land. On the average, a farmer remains no more than four or five years on a rented piece of land. In 1922, 27% of the tenants changed their farms. It would not be too much to say that the American tenant farmer leads a wandering life.

These facts are associated with the change in land ownership in general. Even the full owner does not remain very long on his farm. He is always ready to sell his farm (not as in Europe where farms generally pass from generation to generation). According to an official investigator “most American farms change hands every generation and a considerable number of farms change hands several times in the period corresponding to the average business career.” Investigations have shown that over 88° of the farmers (full owners) bought their farms and only 12% inherited them or obtained them otherwise. The American farmer speculates on the increase of land values and is always on the lookout for a good customer for his farm. For this reason too, he is hesitant about renting out his farm for too long a period.

Land in America is thus drawn into the stream of commodity exchange. Of course commodity exchange in itself is not capitalism but it is a fundamental condition for capitalist relations.

5. The “Agricultural Ladder”: Farm Laborer—Tenant—Owner.

Under such conditions it would be absurd to speak of the dominance of the “family-labor-principle” in the United States. On the other hand the idea of the so-called “agricultural ladder” is very wide spread. This implies: the land does not pass on thru inheritance—the farmer buys it for money; hence every farm hand (farm laborer) can acquire the status of an independent possessor. Didn’t Henry Ford start out as an errand boy? Just so can any sensible, hard-working man, thru hard work, thrift, and business ability, get hold of some capital and mount the ladder: farm hand, tenant, owner.

There can be no question that once upon a time, when there still were wide stretches of uncultivated land and when the situation of America on the world market was favorable, such “climbing the ladder of success” was a widespread fact. Even then, we must remember that such “climbing” was largely accomplished thru speculation—an enterprising man would stake a claim, wait till land values rose, then sell out at huge profit, rake up the money and go still farther West to get down to more solid business.

The situation today is, of course, entirely different although speculation of this sort was still possible only a few years ago (colonization had not come to a complete end and the war boom of 1916-20 prevailed). As a matter of fact, according to the census of 1900, 44.9% of all owners had been tenants and 34.7% had been farm hands. Of 100 tenants in 1910, 33 had already become owners in 1920–in other words, had ascended the ladder. Until a few years ago this “ladder of success” undeniably existed.

But we must not fail to examine the other side of the picture. First, according to the 1920 census, 42% of the owners had never been either tenants or farm hands. Secondly, according to the same census, 47% of the tenants became tenants immediately and did not pass thru the stage of farm hands. Even, therefore, according to the 1920 figures, “climbing the ladder” was not a common phenomenon.

6. Is the “Climbing” Becoming More Difficult and Why?

THE question is not whether the “ladder” exists. No one can deny this. The question is whether it is “used” as frequently as formerly. If we examine the farmers according to their age, it becomes apparent that the number of young people has diminished among the owners and increased among the tenants. In other words, it is becoming more difficult for young people to enter the “sacred temple of property” and, in general, it is becoming more difficult to “climb,” even for old people. If we take farmers of over 53, we find that in 1890 only 14.7 per cent of them were tenants, while in 1920 the proportion was 19.4 per cent. The war has slowed-up this process, but the tendency is clear.

On the basis of such observations the official census report comes to the conclusion that “permanent tenancy” is on the increase in the United States and that tenancy in the corn belt is growing in every way.

Why is the “climbing” growing more difficult? We find this question answered in the material supplied by the Department of Agriculture (Year Book, 1923) concerning the farmers of twenty-five states. The official investigations include: (1) the average prices of farms in 25 states; (2) the average yield of the farms; (3) the per cent of mortgages in these states.

As to the conditions of the farmer who bought his farm on instalments and has mortgaged it, the Department of Agriculture has the following to say: “In none of the investigated regions, except in the Pennsylvania district, is the farmer in the position to spend six hundred dollars a year for himself and expect at the same time to liquidate his mortgage in ten years—that is, unless his original payment was large, much larger than usual.” In Illinois, in the heart of the good agricultural territory, it takes twenty years for a farmer to complete the payments on his farm if his initial payment is one-third or less. To complete payments sooner means to cut deep into the income of his family.

As to the conditions of the tenant who aims at accumulating enough money to become an “owner,” the Department of Agriculture gives an even sadder picture. “How much time is needed to accumulate the first payment for the rest to be paid off in twenty years?” (Here it is already 20 and not 10 years.) “Figures show that only in Pennsylvania is it possible to accumulate anything under such conditions. In all other regions it is impossible. Counting $600 for his own expenses and those of his family and deducting the interest on the mortgage for the whole farm, he will be left with a yearly deficit of from $13 to $1,132.”

The Department of Agriculture maintains that if the tenant wants to become a proprietor in spite of everything he must do one of the following five things: (1) increase the yield of the farm; (2) pay rent lower than the interest on the mortgage; (3) obtain the initial capital from the outside and not as a result of his labor and frugality; (4) spend less than $600 a year for living expenses; or (5) utilize the labor of his family “without wages.”

All this, of course, is possible to a greater or lesser extent. But does it not prove, first, that the “ladder” is here entirely broken down and, secondly, that the American farmer is approaching very close to the European peasant with his stinting his own family for the benefit of the land monopolist? The discussion of the Department of Agriculture concludes: “Thru one of these means 4 great number of tenants succeed…making their first payments. On the other hand, the analysis of the figures shows that under average conditions this process has become very difficult in many parts of the United States.”

What is responsible for this breaking down of the “ladder”? More than everything else the increase in the price of land. In general, it can be said that the dearer land is the fewer chances has the tenant of becoming full proprietor.

Two forces operate in this direction.

a. If prices rise quickly, then the proprietor wants to keep his land and, if he does not work on it himself, he rents it out to a tenant (for a short term—as we have seen). If the prices rise quickly the proprietor incorporates future increases in the price of his land, and so the price becomes ever more inflated. There therefore arises a great difference between the yield that the proprietor could get from the soil by working on it and the “value” that arises from speculation on the general increase in land prices. The produce that the tenants obtain comes from only one source: his labor on the land. But the rent he pays is of a double nature: (1) “production rent” and (2) “speculation rent.” It is evident that from production alone the tenant can never accumulate enough capital to buy land at its speculative price. (This is especially noticeable in Iowa, where the increase in land prices has taken place with unusual rapidity.)

b. More important, however, is another factor, The absolute price of a farm is becoming so high that it becomes impossible to buy any land. According to the census of 1920 the average price of a farm in the United States is $12,084 (soil and buildings amount to 85 per cent). In the best agricultural areas the price of a farm is $25,517; in second class sections the price is $15,898. In 9 per cent of the counties of the United States a farm cannot be obtained under $85,000 and in 3 per cent under $50,000. Of course the inflation of prices was partly due to the war and now they are relatively lower, but it is clear why it is ever more difficult for a tenant to mount the “ladder.”

7. Growth of Tenancy According to Time and Place.

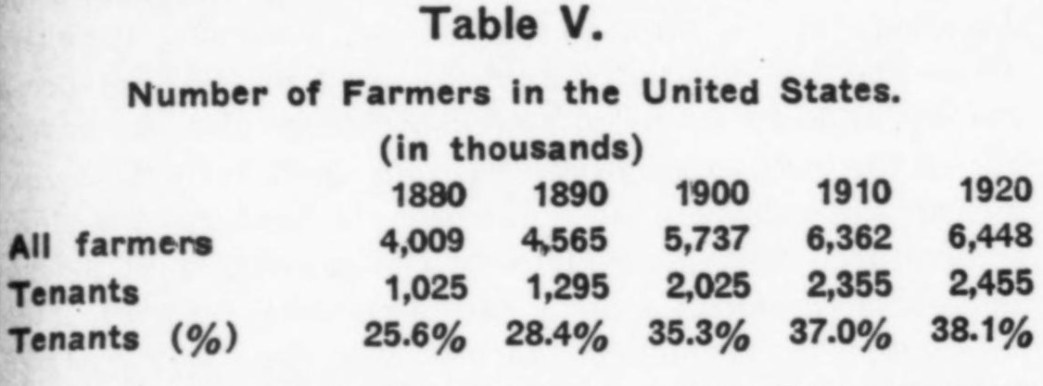

The following table. (Table 5) gives a picture of this development.

This table shows that in forty years the percentage of tenancy has risen greatly: it was 25% in the year 1880, 38.1% in 1920. At this time the percentage must certainly be still higher. Especially great was the rise of tenancy between the years 1890 and 1900 because that decade was marked by a fall in the price of land owing to the general over-production then beginning to be felt in the United States.

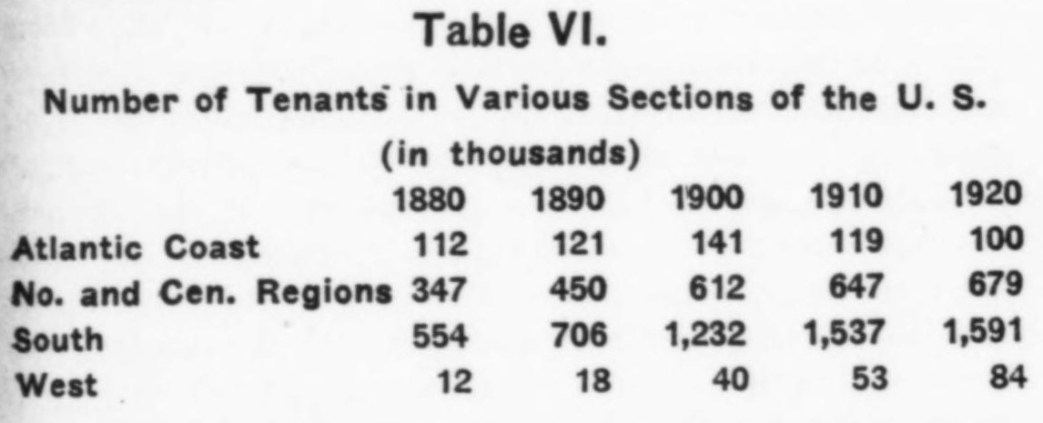

The growth of tenancy according to place is expressed in Table 6.

In the Atlantic States the price of land has recently fallen quite a good deal (competition of the more favorable regions in the North Central States and the West). For this reason it has become much easier there to purchase a farm. In general farming plays an ever smaller role in that industrial section. The number of tenants has fallen. In the North Central States (wheat and corn belt) tenancy has shown a rise both absolute and relative—until now it takes in one-third of all the farmers. In the South, where a portion of the former slave plantations had been divided up into smaller portions and rented to the Negroes, tenancy had reached fifty percent. In the decade from 1910 to 1920 the growth of tenancy abated owing to the exodus of Negroes to the northern industrial centers.

This development becomes especially clear when it is compared with that of Canada, so close a neighbor of the United States. There the proportion of tenancy has kept falling regularly: in 1891—15.4 per cent; in 1901—12.9 per cent; in 1911—11.4 per cent; in 1921—7.9 per cent. Canada still has great land reserves—and the “rent sharks” have not succeeded as yet in laying their claws on them.

8. Tenants Paying in Kind.

If we want to understand the agricultural conditions of the generality of tenants, if we want to understand the significance of the domination of the land owner over the land worker, we must realize that there are various groups of tenants. Chief among these groups are: tenants paying a definite money rent, and tenants paying a share of the produce (“share-tenants”). The first class own their own tools, machines, horses, seeds, etc. The farmer who belongs to this class is entirely independent of the land owner; therefore his risk is greater (in case of bad crops or low prices) and he pays less in rent than the share-tenant. The latter does not own his own means of production—he receives all of them from the owner who also keep his eye out that the farm should be worked in the proper way. In such a case the owner generally receives two-thirds of the produce, the share tenant one-third. Of course, in the case where the share tenant has his own tools and seeds he pays less, usually one-third.

Croppers are that type of share tenants in the South (usually Negroes) who receive everything from the owner, often even food. As a result, they are practically the slaves of the planters and yield up to them the greatest part of the cotton. In 1920, the number of these croppers was 561,000—that is, almost a third of all the tenants in the South and approximately 23% of all the tenants in the country. The farms of the croppers are very small: although they make up 23% of all the tenants they Own no more than 8.5% of all the tenant land. Their farms are on the average 40.2 acres. They are in fact the serfs of the southern lords although nominally they are free.

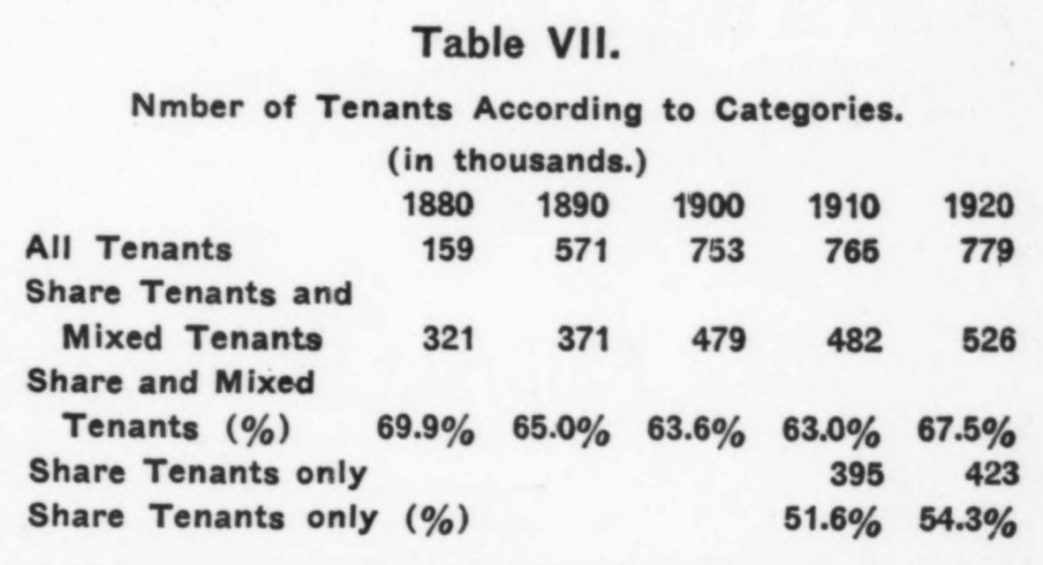

If we exclude the South and consider the share tenancy in the northern agricultural areas we get the following facts:

This table shows: (1) that share tenancy, pure and mixed, occupies the greatest place in the northern agricultural center (approximately two-thirds); (2) that from 1890 to 1910 the percentage of share tenancy was on the decrease; afterwards, after 1910, it began to grow again and reached a higher level than in 1890; (3) that the amount of pure share tenancy has also grown. Share tenancy as a whole occupied in 1920 about 72.2%of all the lands held in tenancy in that region.

What do these figures show? They show that between 1910 and 1920 it became particularly difficult for the tenant to rise on the agricultural “ladder,” that he was more and more compelled to fall back on share tenancy, that he became more and more dependent on the owner, developing into nothing more than an official of his, in the best of cases—his partner. A large part of this was the result of the war-time high prices of agricultural machinery, but even more was this a result of the war time growth in land prices which forced up rent to a higher degree.

9. Various Groups of Tenants.

The lowest rank among tenants is occupied by the croppers who are hardly any freer than the slaves of the old times and whose wages are much smaller than the wages of ordinary hired labor. Such croppers are also found in the North. They pay two-thirds or a third of the produce.

The next group are the average tenants who no longer hope to become owners and who aspire only to have enough to eat for themselves and the family. These might be called the professional tenants on the type of the European peasant…

The third group is the middle peasant who hopes to become an owner, who is “climbing the ladder.” He has a little capital that he brought in when he became a tenant. He frequently changes his farms, always looking for larger and better ones. He absolutely refuses to remain a permanent tenant. Whether he pays cash or a portion of his produce—he always is “climbing.”

The fourth group is made of middle and large enterprisers. A member of this group does not as a rule work himself. He manages a large agricultural enterprise in which he has invested his capital. The land is hired because he has not enough capital to buy land and because he finds it more profitable to invest his capital in machines, cattle and other stock. Naturally, a member of the third group aspires to reach the fourth in which we find cash tenants as well as share tenants.

The fifth group is at the opposite pole of the cropper. They are the partial tenants who themselves own land, only they hire more land to increase their economy. They are largely capitalists, middle and large. Their tenancy is no sign of dependence; it is a result of their desire to broaden their own capitalist enterprises.

These are the facts. What is their social and political significance?

In recent years the farmer movement has grown in America. If we want to understand its roots, its character and its necessary aims as well as the prospects for an alliance between this movement and the struggle of the industrial proletariat, we must investigate basically the relations of production in modern American agriculture. This also gives us the possibility of seeing the class divisions among the American farmers. We also come to see clearly the role that the various strata can play not only now but also in the whole of the future. The work necessary in this direction was begun by Lenin in his work: “New Data on the Laws of Capitalist Development in Agriculture.” We have attempted to go a little further in the direction he has pointed out. We have given our attention exclusively to only one field of the relations of production, the land relations. But this is an exceedingly important field, the land question in the country. districts being that question about which the class struggle breaks out first of all. In this connection the United States is no exception. Hitherto, the chief characteristic of the struggle has been the fact that the growing class of “rent takers” kept on grabbing the land at the expense of the direct agricultural producers or the direct managers of the agricultural process. Now the struggle is taking on the character of an outspoken struggle of the direct producers and partly of the direct managers of the agricultural process (that is, tenants of a petty bourgeois and bourgeois type) for the return of the soil and for the removal of rent which acts as a fetter on the forces of production.

The Workers Monthly began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Party publication. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and the Communist Party began publishing The Communist as its theoretical magazine. Editors included Earl Browder and Max Bedacht as the magazine continued the Liberator’s use of graphics and art.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/wm/1926/v5n09-jul-1926-1B-FT-80-WM.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/wm/1926/v5n10-aug-1926-1B-FT-90-WM.pdf