We lose far more often than we win. Helen Norton looks at the forces that defeated the courageous 1931 strike led by Frank Keeney’s independent West Virginia Miners’ Union.

‘Outcome of West Virginia Miners’ Strike’ by Helen G. Norton from Labor Age. Vol. 20 No. 9. September, 1931.

HUNGER and “legal” violence have beaten back the West Virginia Mine Workers in their first skirmish with the coal barons. After six weeks of unequal struggle the union has been forced to order its members back to work in the mines controlled by the Kanawha Valley Coal Operators’ Association with no other concession than the operators’ promise not to victimize the union members. The strike is being continued, however, at the mines of seven non-association companies in the hope of getting individual agreements.

There was a surprisingly generous response to appeals for money and clothing, considering the isolation and limited area of the strike. Unions from all over the country sent contributions—garment workers, miners, railway workers, butchers, building tradesmen, food workers, teachers, hosiery workers, and printing tradesmen. Miners’ locals in Illinois sent regular assessments.

The C.P.L.A. collected funds from 14 states. The Emergency Committee for Strikers’ Relief sent substantial amounts each week, which were the backbone of the relief work. The Church Emergency Committee, the Chicago branch of the League for Industrial Democracy, Consumers’ Cooperative organizations, and Young People’s Socialist League groups contributed substantial sums. Individual contributions ranged from $1 to $1,000.

Nevertheless, not enough money came in for the colossal task of feeding 7,500 miners and their large families, even on the limited rations issued by the union. As the strike progressed it became more and more evident that to attempt to prolong it would merely result in large numbers of miners being starved back to work until the more loyal unionists would find themselves shut out of the mines permanently. On several occasions trucks coming in for food supplies had to be sent back empty because the wholesaler refused further credit. Strikers were wholly dependent upon the union for food because the scrip system of payment precludes credit at independent stores.

380 Eviction Cases

Legal violence against the miners took various forms—evictions, injunctions, intimidations, arrests. Some 380 eviction cases went through the courts in the six weeks of the strike, all but four of which were decided in favor of the company. At Ward, where the Kelly’s Creek Collieriers Company was desperately anxious to break the strike, 58 of the earlier cases were appealed, over $9,000 in cash for bonds being furnished by Mrs. Ethel Clyde of New York. Some appeals were taken in other places, but it was utterly impossible to furnish appeal bonds for more than a fraction of the cases because of excessive damages alleged by the companies. Two hundred more Ward eviction cases were scheduled for the week of August Io, 41 at Hugheston, and a large number on Cabin Creek. Three tent colonies have been established—at Hugheston, Blakely, and Cabin Creek.

The constable who evicted the Hugheston families was assisted by two men who had sat on the jury when the cases were tried. Families were not allowed to take anything from their gardens at Blakely but had to leave it for the scabs whom the company imported to take their jobs.

Intimidation was to be found everywhere. Company guards—seemingly all the thugs and riff-raff of the county were rounded up and given arms—rode up and down through the camps and terrorized the tent colonies. One guard, rendered too enthusiastic by West Virginia corn licker, fired into a union crowd at Burnwell, shooting a white-haired woman in the abdomen and wounding a boy. He was bound over to the grand jury, but so were five miners, charged with throwing sticks and stones at him as his fellow guards hurried away. Two mine superintendents assaulted strikers—and were highly indignant when they were arrested and fined. The county jail was full of strikers, arrested on pretexts ranging from trespassing on company property to being found with wet shirts after shots were fired at a scab train during a shower. Picket lines were turned back by state police, access to the post office denied, and every effort made to provoke the strikers to violence.

The extent to which coal production has been cut down is somewhat problematic. The operators’ association admitted that railway car loadings were cut 114 cars in the second week of the strike but the actual cut in production was undoubtedly a great deal more because reserve coal piled along the tracks for months was then loaded. Certainly a great many of the mines were effectively tied up, but with the vast over-development in the field, a fifth of the mines working six days a week could produce as much coal as all the mines working their normal shifts.

Scabs (called transportation men in West Virginia) were brought in by some companies and at Ward, where there was a particularly fine spirit between white and colored workers, large numbers of Negroes were imported with the evident intention of creating race feeling. However, the chief menace to the union was not imported scabs but the great number of unemployed miners already in the area. It speaks well both for the effectiveness of the union’s organizing campaign and the innate class consciousness of the miners that, despite the tempting offers of the operators and the uncertainty of strike relief, comparatively few of these went into the mines.

One of the greatest aids in keeping up the morale of the strikers was the Labor Chautauqua conducted by the League for Industrial Democracy under the leadership of Mary Fox. This group of I4 young men and women was in the field seven days a week for six weeks, giving labor plays or talks on history and economics, leading singing groups, organizing children’s recreation. The wail that went up when their stay expired and the extent to which they drew out the native ability of the local groups in speaking and singing suggest that the chautauqua program is perhaps the form of workers’ education best adapted to this field.

Strike Breaking U.M.W.

The United Mine Workers were a negligible factor in the strike situation. At the beginning of the strike, William Houston, Lewis appointee to the presidency of District 17, appealed to the miners to remain at work and to the public to ignore the strike. Later he and other Lewis men went about the field telling the men that the U.M.W. could get a contract for them without a strike. “Oh yeah?” was the reply they got from the miners, who knew that the recent contract in the Morgantown area provides for a scale even lower than the prevailing rates in the Kanawha Valley. The National Miners’ Union has so far not attempted to enter the Kanawha field beyond sending in a few scouts.

However, the Communist bogey was raised repeatedly. Houston reports in the United Mine Workers’ Journal that “this struggle is not directed by miners but is being directed by a bunch of New York Communists.” Apparently he generously lumps the C.P.L.A. representatives such as Tom Tippett, Lucile Kohn, and Katherine Pollak and the Labor Chautauqua group under this heading. Houston prophesies the failure of the West Virginia Mine Workers, after which “it will be possible for the old reliable United Mine Workers which has done so much for the miners of this country in the years gone by to put on a real campaign of organization which will bring real results to this field.”

For seven years, since the resignation of Frank Keeney and other officers of District 17 in protest against Lewis’ suicidal “no backward step” policy, the “Old Reliable” U.M.W. has been in the West Virginia field—or at least in its Charleston office—and the “real results” of its tenure are all too apparent. Local unions were allowed to go into complete decay, checkweighmen disappeared from the tipples despite a state law making them mandatory if a majority of the men demanded them, and wages have been driven down to unbelievable levels.

How much can be salvaged from this initial struggle of the new union remains to be seen. So far there has not been any flagrant victimization of strikers, but that is no sign that the coal operators have “got religion.” A permanent union structure, such as is now being planned, must be maintained or their despotism will soon reassert itself.

A few of the operators who pay relatively high wages were inclined to deal with the union and undertook to argue the whole association into doing so on two occasions with the theory that a union would help whip into line the low-wage operators who are now undercutting the others on contracts, and the fight could then be extended into Logan County, which has been getting more and more of the Great Lakes coal trade. However, the majority of the association operators were obdurate in their determination not to deal with any union, and the negotiations fell through.

It would be possible, of course, to call the operators’ agreement, to take the men back without victimization “a glorious victory” and to say that the correspondence and conversations with individual operators constituted “recognition of the union” thus creating the pleasant fiction that most of the objects of the strike had been accomplished. Certain A.F. of L. organizations have won many such “victories” in recent years. I prefer to say that the outcome of the strikes is in a considerable measure a defeat, and to recognize it for what it is, as presumably all Progressives have the courage to do. Insofar as it is a defeat, however, it is an honorable one and almost inevitable.

The new union, hampered as it was by lack of funds and by the fiasco of the Reorganized U.M.W. movement in Illinois, took a long chance in calling the strike. However, the only alternative, in face of the operators’ ruthless victimization of men who joined the union, was to abandon all attempts at organization. Although the union has made very slight tangible gains this time, it has at least demonstrated to the operators that it can control the men in the field and that they can no longer starve and victimize their workers without opposition.

The spirit of unionism, dead these seven years in West Virginia, is alive again. “We’re licked this time but we’ve got to keep the union going’—this was the sentiment of the miners at every meeting when they were told what the situation was. They are grand, these gaunt, poverty-bitten victims of capitalism’s senseless exploitation. And they are aware, as they perhaps have never been aware before, of the extent and shamelessness of that exploitation. It is no longer individual hard luck, local suffering that they see. They have visualized the whole bitter struggle of the workers. What will remedy it? Trade unions, political action, workers’ control—the answers come quiet and sure in their southern drawl; answers not learned from any books or parlor pink debates, but learned from life. “I want to go to Brookwood so I can come back to West Virginia and make an agitation,” says one young miner.

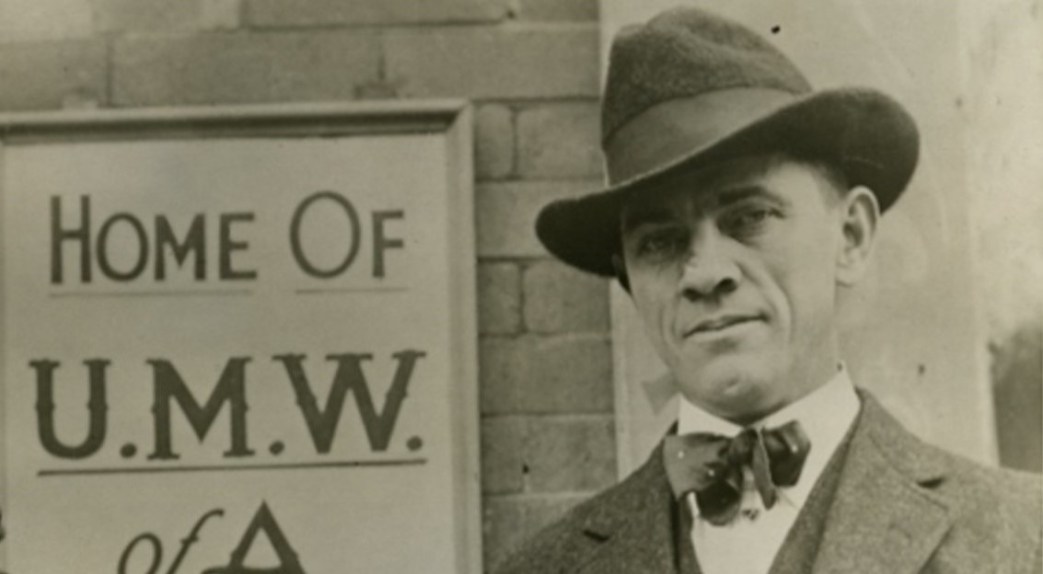

With this spirit and with the courageous, intelligent leadership of their president, Frank Keeney, and other officers, the miners are determined to carry on the fight for unionism and against feudalism in West Virginia. It will be a long fight and a difficult one, in which they will need the backing of every progressive worker in the country.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v20n09-Sep-1931-Labor%20Age.pdf