A report from Agnes Smedley in Shanghai on a Left, particularly artists and intellectuals, that not only survived the bloodbaths of 1927, but which was thriving anew and remaking revolutionary China.

‘Thru Darkness in China’ by Agnes Smedley from New Masses. Vol. 6 No. 9. February, 1931.

The past two years in China have witnessed a decided and rapid swing to the Left of the young Chinese intellectual world, following the establishment of the Nanking Government three years ago, with the terrible slaughters that accompanied and followed it, those revolutionary elements that remained alive, but chiefly the intellectual elements, either drew back in fear or indecision, or waited, hoping Nanking might do some good to the country. But the wars of the rival generals within and without the Government continued, the vicious suppression of the peasants and workers continued unabated, and the masses of the country were loaded with ever new taxes and burdens to fill the pockets of the generals and finance their wars. Slowly the disrupted intellectual world began to coalesce. To the right went the Fascist intellectuals into the Kuomintang, or in cooperation with it. And those who had revolutionary tendencies, vacillating up to that time, went to the Left, at first critically and protesting, then bitterly, and then into organized action. The last year has witnessed a swift swing to the Left behind the Communist peasant armies. The fight of the peasant armies has been like an electric current through revolutionary intellectual China. New social theatres have sprung up, Left writers began to confer, Left artists turned more to the new art of Soviet Russia and Germany, and literally dozens of volumes of new literature, chiefly Russian translations, tumbled from the press, and even conservative publishing houses found the sale so profitable that they published them, counting on quick returns sufficient to cover all expenses and bring in a good profit in case of suppression.

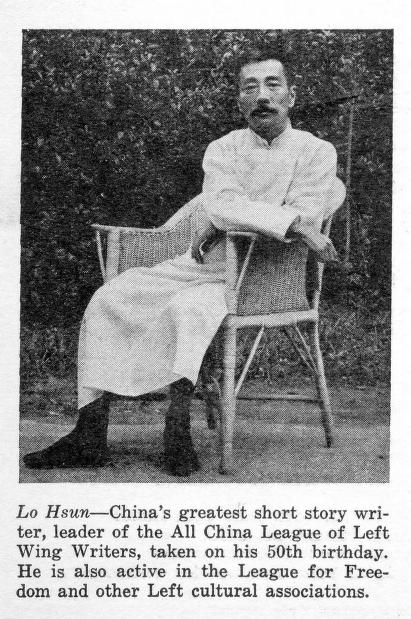

In the Spring and Summer of 1930, all this Left world began to coalesce into a united front. First came the organization of the All China Social Scientists’ League, with headquarters in Shanghai and branches in various parts of the country and Japan. Here were organized professors, writers, and teachers. They issued a manifesto in which they declared it to be their purpose to spread Marxian science and to participate actively in the social revolution. During the Summer other cultural organizations were formed. Most interesting of these was the League of Left-Wing Writers of China, one of whose active members was China’s most noted short-story writer, Lo Hsun. Formerly vacillating, and critical of the social revolutionary writers, Lo Hsun now joined the social revolutionaries “bag and baggage” as one hostile critic expressed it. And when Lo Hsun went, he took with him a huge following of sympathizers, for the students and intellectuals of the young and middle generations have been nurtured on his writings.

Close on the heels of these new organizations came the League of Left Dramatic Societies. There are some fourteen small theatrical clubs, groups and theatres in Shanghai, of which three can be called theatres. Chief of these theatres was the Shanghai Art Theatre and the Nan Ko Theatre, the latter five years old, the former appearing January, 1930. Formerly the Nan Ko was dominated by Bohemianism and an “art for art’s sake” attitude, but after all, even as an artistic group, it found the present society and forms utterly empty, uncreative, stupefying. So it went to the Left with giant strides and those of its members who doubted were brushed aside. Tien Han, its head, led the advance. The Shanghai Art Theatre had presented a number of dramas — Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front, Sinclair’s Second Story Man , Romain Rolland’s Game of Love and Death and Maerden’s Coal Strike, and was preparing for the Russian drama, Roar China, when the heavy hand of the law fell upon its shoulder. The Shanghai Art Theatre leads, and always led, to the Left.

Then, as if not to be left behind, came the formation of the League of Left Artists and all those who could push a brush — to the Left — joined. Close upon its heels came the Union of New Book Shops — which is a peculiarly interesting development in China, because of the dozens of new book shops that publish or circulate — well, we will call it the “new literature.”

In September came the organization of the Federation of Left Cultural Associations of China, composed of the above — social scientists, writers, artists, theatres, book-shops; and thereto the League for Freedom, founded by intellectuals months before to propagate freedom of the press, speech, organization and the strike; also the League against Imperialism, and the International Red Aid. The Federation was headed by a committee of elected delegates from all branches, it imposed rigid discipline upon its members, and began intense activity amongst doubtful intellectuals. Its various organizations carried on work in their own field. The Social Scientists’ League, for instance, had already a record of great activity. It has branches in many universities, its Tokyo branch started with 40 members and has for months published an excellent monthly magazine, The Struggle. The League in Shanghai published a number of magazines: The New Thought; Lectures on Social Science (much like the German monthly, Under the Banner of Marxism); the International Magazine (an anti-imperialist monthly); the Social Science Front, their chief journal. New Thought carried on for seven issues before it was suppressed. It openly published the foundation names of the members of the League and informed the Kuomintang in direct words that it was out to fight it to the death, and likewise to support the Chinese Soviets to the death. Lectures on Social Science, however, appeared but once before it was suppressed, as did the International Magazine. The latter magazine did not have a line in it about China, but only articles on imperialist exploitation in colonial countries — still the Kuomintang didn’t like its contents.

The League of Social Scientists also began to carry out an extensive program of publishing small text-books for mass education in Soviet districts as well as in other parts of China. These covered such subjects as: the history of the Chinese revolution; its present stage and tasks; the land problem; labor, youth, and woman problems; the peasants and the revolution; problems of proletarian dictatorship; the revolution and the Communist Party; Fascism; Leninism; Marxism; various economic, social, and political problems; imperialism in the colonies with studies of revolutionary struggles in the colonies; and every phase of the Soviet system in the Soviet Union.

The League of Left Wing Writers, also many months old, had begun an interesting and significant struggle. In the August 4th issue of its small weekly journal appeared a resolution of which the following is a part:

1. The present proletarian literary movement in China must fight for the existence of Chinese Soviet power…The problems confronting the League are: a) how to help raise the political, educational and cultural level of the masses; b) to aid the working class in a realization of its historical task; c) to unite revolutionary sentiment and historical development. 2. To create a workers and peasants correspondence; to create a reportage movement through schools, factories, and villages concerning the war between the White and Red troops.

The resolution also discussed the mistakes and weaknesses of the past, such as the lack of full development of the theoretical struggle in China; the lack of reality in the present school of writing; the literati belief in the “almightiness” of writing; the tendency to legalism; the remnants of individualism. It further announced its determination to unify writing and labour, making it compulsory upon all members to take active part in the social revolution and to create a literature only from reality.

Of course the Kuomintang and the Nanking Government struck right and left. Like the Imperial Japanese Government, they try to crush all “dangerous thoughts,” and the methods they have used and continue to adopt are a perfect copy of Japanese methods. All of the Left organizations and members felt the heavy hand of these generals and politicians. The Shanghai Art Theatre, whose productions sound mild indeed to Europeans, was suppressed and some of its members arrested. The most of them live in hiding. The Nan Ko Theatre was suppressed on the third night of its production of Carmen. The room of its leader, Tien Han, was later raided, and he fled to Japan, where he now lives in exile. He is a brilliant, erratic genius, not unlike the prerevolutionary Russians, and has written many one and two-act dramas of artistic and social significance.

Of course, the Left Wing Writers could never escape. Moung Ya (Grass Sprouts), that brilliant literary magazine of which Lo Hsun was the publisher, was suppressed. In its stead sprang up The New Land and The Pioneer, both of which went down under the combined charge of British and Kuomintang police. The Partisan and The Masses fob lowed. That intensely interesting little weekly, The Cultural Struggle, which appeared from the beginning of the League’s organization, is the only one now existing, but neither it nor any of the other Left magazines that formerly appeared in Shanghai can be sold in the book-shops, as formerly. Most of the Left Wing writers, including Lo Hsun himself, live in secret and some are in exile.

It was of great interest that, despite the White Terror, a large gathering of these men and women met on September 17th in Shanghai to celebrate the fiftieth birthday of Lo Hsun, and that some of their members then announced that the Nanking government had issued a secret order for the arrest of some fifty Left writers, among them Lo Hsun.

The fight against “dangerous thoughts” was carried out all along the line. The college that had been founded in Shanghai by the Social Scientists’ League was raided by the police and suppressed. In Peking, 60 students in the National University were arrested and imprisoned in October for trying to found a branch of the Social Scientists’ League there. All publishing houses and bookshops in Shanghai and other cities have been ordered by the Kuomintang to sell no magazines or Left literature. And to counteract the new cultural societies, the Kuomintang proposes to start what it calls a “national book-shop” where “the tastes of youth will be ignored” and books and magazines of a “decent, respectable” nature will be offered the revolutionary youth of China! So, before long we may see a book-shop filled with volumes written by American bankers, bourgeois professors of economics, ex-presidents, and factory owners. A Chinese Kuomintang professor has also come to Shanghai to start a “new” theatre to prevent Communists from “corrupting the youth of Athens.” This new theatre will be financed by the Shanghai Chinese Municipality which is headed by really bloated Generals.

The White terror rages in every field in China. And yet the revolutionary intellectuals do not draw back. It often seems that they, in common with the Chinese masses, have passed beyond death or fear of death. Their struggle is not the romantic fight that poets and writers in far-away countries like to imagine. We who sit relatively near to them can never know what is going on. But it is known to all who can read that men and women suspected of being or proved to be Communists are savagely tortured in every part of China these days and are then either shot or beheaded in the streets. When Communists are caught in Hankow or other cities, the generals and other Kuomintang gentlemen have adopted their final method to prevent their victims from shouting slogans as they go to their death. Formerly these prisoners walked to their death, shouting: “We die for the sake of Communism!” But now they don’t. They can’t because their tongues are first cut out, or their mouths are stuffed with dirty rags. With blood trickling from their mouths, and already half-dead from torture, they are taken to their death. In Canton, a high official and banker said to me personally: “I don’t know what it is, but there must be something attractive in Communism for our students. When we take them out to be shot, men or girls, they go without fear, shouting: ‘We die for the sake of Communism! Listen everybody! We die for the sake of Communism!’”

There is no coming from prison, a hero and a martyr, for the revolutionary youth of China. Over the path pointing the way to the social revolution are the words: “Abandon hope, all ye who enter here!” Abandon hope— -or does one? The revolutionary Russian workers have a proverb which they formerly often used: “Even if they burn the snow, there still remains for us the ashes.” Only the ashes! And yet recall — is there not a story somewhere of a Phoenix arising time and again from dead ashes?

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1931/v06n09-feb-1931-New-Masses.pdf