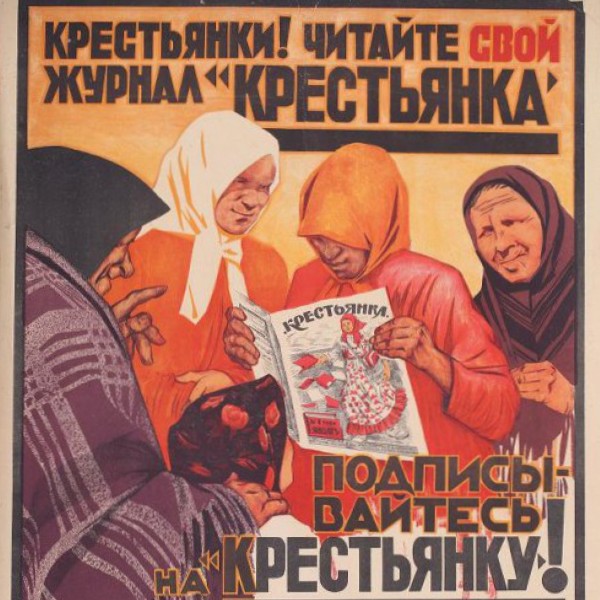

Morris Backall reports from the Soviets on the changes in society represented by the magazine “Krestianka”, written by and for peasant women.

‘“Krestianka” (Peasant Woman) in Soviet Russia’ by Morris Backall from The Daily Worker. Vol. 2 No. 243. October 24, 1925.

“KRESTIANKA” (Peasant Woman) is a magazine issued monthly in Soviet Russia that represents and reflects the needs, problems, strivings of the woman in the villages of Soviet Russia. It is a magazine that contains articles, short stories, reports, and illustrations, also letters written by the women of the village that are scattered all over the big land that is now consisting of socialist Soviet republics, and forty nine languages are spoken in this land of Communist life and activity. Who does not know the life of the Russian “Baba” in the former times in the Russian villages? The peasant woman was a slave of slaves. She worked together with her husband the mujik in tilling the soil. She raised children, she cooked the meals, spun the cloth, kept the household and was the object of the anger and drunkenness, darkness and bestiality of the mujik. The Russian peasant was illiterate, was kept in subjection, worked in a primitive surrounding, and the tragedy of his life was the double tragedy of his wife, who suffered equally as he and also because of her lower place in society. She was not considered an equal person, and therefore she felt the beating of her husband and the insult of life in a degree that is hard to imagine.

The Soviet government brought equality to the woman in the village, who is not only a worker, but also a mother to children. She keeps in her hands the future generation of the greatest part of the population. “Krestianka,” the magazine for the peasant woman, tells us the story of the new freedom, of the new place that the woman in the village occupies in the life of building up the workers’ and peasants’ republics of Soviet Russia.

We see in the magazine “Krestianka” a report and a photograph of a general convention that was held in Moscow in March of this year of workers among the peasant women. The delegates were simple women of the villages, among them we saw Krupskaia and Kalinin. They deliberated about the problems of the woman in the village, not only how to get her interested in the Communist movement, but first of all, to get her to understand that her position in life is now based on equality in the economic, political, and cultural spheres. She is not any more the inferior slave of the husband, of the officer of the village, but she has the right and the privilege to participate in all Soviets and the elections, that she is equal before the law, that she has the right to stand up against the insults of her husband, of the kulak (rich peasant), or the factory owner. In the report of this convention the active workers in the villages demonstrated the great spirit of awakening that goes on in those little huts among the poor peasant women in regard to education. Peasant women go to the elections of the village Soviets, put up their candidates, are elected to these Soviets and spread propaganda for it. They are judges in courts of the village and village district, they take an interest in education, they feel that as mothers they must be in a position to be able to help their children in their work in schools.

The little school houses that are to be found now in a great deal of villages contain a “Lenin corner” decorated with red ribbons, with a little library. Who are the ones who organize those corners? The peasant women. They donate pounds of flour, bushels of wheat, sell it, and for this money they buy the necessary books, magazines for the Lenin corners in the schools of the villages. After a long day of hard toil on the field, after they put their little children to bed, the peasant women get together in these school houses and study with the teacher that was occupied all day with the children, or the teacher reads to them the news of the Soviet papers, especially the articles that are connected with their own life, and those that give information how to improve their agricultural activities and their house and homo problems. Celebrations are organized at the openings of these Lenin corners.

In “Krestianka” we find very many letters sent in by peasant women. They are coming from Ukrainian villages, from White Russian villages, from Caucasia —Cossack women. These letters represent the “bit” (mode of life) of the present village. A revolution goes on in the village, the past did not disappear yet, the hundreds and hundreds of years of darkness, prejudices, illiteracy, domination of priests is yet felt very much. It could not disappear entirely yet.

The mujik looks with suspicion when his wife goes to the election of the village or village district Soviets. Many quarrels occur on account of it. The women were ridiculed at the beginning and many peasants expressed their disapproval of the “baba” becoming an equal, but enlightenment changed the situation somehow, the women organized meetings at which speakers explained the new spirit and position of Soviet Russia. The meetings of women discussed the needs of the life and existence of the village community, so the men began to understand that the differentiation of sex Is only artificial in regard to social and economic problems. The women of the Russian villages carries the burden of life as well as the men and in addition, they raise the young generation.

The great mystery of the existence of the Russian village was the peasant woman, her energy and her endurance was the great secret that could keep the village community alive. Now, with her awakening, development and enlightenment, the Soviet government brings into play an element that will astonish the world with its power and with its possibilities. We read letters how peasant women in Soviet Russia, on their dying bed, are asking their children not to call the “pop” (priest) but to make them a red funeral, or how a peasant woman, decides that she has to devote her life in working for her sisters and goes to a large town to study in a workers’ school. The whole village goes out to give her a send off and everybody is expecting to receive letters of instruction of what to do in order to serve the community in its needs.

In “Krestianka” we find also letters that tell us of tragedies in the village of Soviet Russia. The husband comes home in some cases drunk, and still beats his wife. A kosac woman tells in detail that her whole body is covered with wounds and that she went to the court of the district and the judge issued a divorce immediately and divided the belongings in half so the Russian peasant woman of today has a protection against the brutality of those that are yet ignorant of the equal rights the Krestianka enjoys in Soviet republics.

The peasant women organizes assistance for the poor children of the village that have no clothes or shoes to go to school. They co-operate with the teacher of the village school, they help in the building up of the new educational system in their land. They organize nurseries for the summer when they are busy on the field, and the school teacher or the organization worker is left with the children.

It is remarkable to note the tune of the district and gubernatorial conferences that are held of the Russian peasant women. The frank statements of their situation demonstrates to us how in Soviet Russia out of the depths of the villages grows a woman that is looking realistically about her position in life. The reports of these conference are full of description how their husbands treat them, what they demand, what they do, and what they hope for their future.

There is also short stories in the “Krestianka magazine. They picture to us the yet poor conditions of the Russian villages, but, it is full of heroism and success how these simple people are ready to sacrifice their own personal well-being for the greater needs of their community.

How they look with prejudice at the beginning, at every new person coming in their midst, and every new mode of life that is brought in the village, but after finding out the truth about it, they accept it with a religious fervor. The short stories picture to us the new relation to children; the child in the village is ceasing to be a private owned object as well as the woman used to be in these localities. The child is more a communal member. In one of the stories a peasant meets a little child, a girl, on the field in a cold, winter morning. He recognizes the child and is asking, “Why do you not go to your uncle?” The child does not answer but sheds tears, and the peasant understands why the child cannot go back to its uncle. He calls to his imagination the beatings the child received so he takes the child on his arms and carries her back to the village Soviet, peasants are present in the village Soviet, everybody looks at the child and when the commissar asked for bread, every peasant was stretching his hand with bread to the child. When the child satisfied its hunger the commissar was ordered to take the child back to its uncle, but the youngster cried again, and the commissar understood the reason and said, “We will drive over to the children’s home in the district.” The child smiled, and every peasant remarked in the years to come this girl may occupy a big position in a Soviet herself.

This position in regard to children in the Russian village is a great factor in relation to the future life of the Russian Soviet peasant population. The “Krestianka” contains questions by many village women, in regard to the education of the children, how to build community houses and even legal questions pertaining to the cruel attitude of some husbands towards them. The magazine answers all these questions and instructs the woman about the laws of the Socialist Soviet Republics.

Like in every other corner of life, this remarkable work among the women in the Russian Soviet villages proves that only a government of the working class and peasant population is able to deal with every problem of life in a realistic and concrete fashion. There is no hypocrisy, conventionality, prejudice towards a problem that is surrounded with so much falsehood in our capitalistic states: The problem of equality of women in economic, and cultural sense.

The peasant woman of today visits the working women in cities, becomes familiar with the factory life, union conditions, problems of work, and brings it back to her sisters in the villages, and hammers out close relations between the city and the village.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1925/1925-ny/v02b-n243-supplement-oct-24-1925-DW-LOC.pdf