It was rare enough for a labor publication to address the world of Black women in the early 1920s, even rarer for it to be written by a Black woman. Here Emma L. Shields, an educator and graduate of Fisk investigating for her report on Black women in industry for the Women’s Bureau of the Department of Labor, looks at the specific role of Black women’s labor in Southern tobacco processing, and the internal racial dynamics in the process of making cigars.

‘Negro Women and the Tobacco Industry’ by Emma L. Shields from Life and Labor (N.W.T.U.L.). Vol. 11 No. 5. May, 1921.

“OH, YES, Negro women have been working here since 1875. Take Sally there she and those six older women you see have been here between thirty and forty years. They feel that they belong to the firm, and to me–so much so that think of them as my property.”

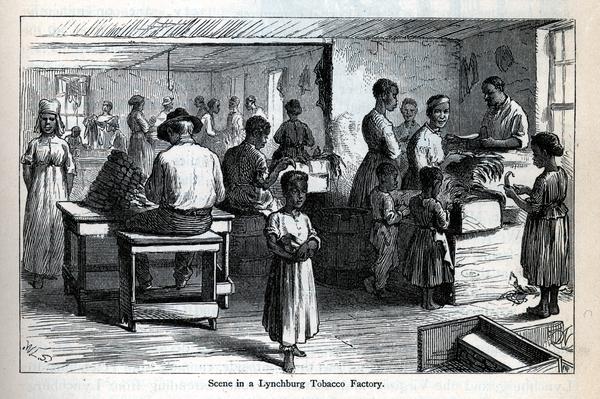

Thus is the historical background of the Negro woman in the tobacco rehandling plants of the South well depicted by one employer. This process in the manufacture of tobacco has been conceded to be exclusively within the province of Negro women ever since the factory method of rehandling tobacco was evolved. Many Negro women bent low with years of toil have been employed in this work with the same firms since the factories were first built, years and years ago, until now they have a childlike sense of obedience, allegiance and loyalty to those employers in whose service they have spent the best part of their lives.

A point of view is also indicated in the words quoted above. Not only do many old Negro women feel that they belong to the firms in which they are employed, but their implicit faith and confidence, on the one rand, and their servile fear and suspicion of their employers on the other, is both beautiful and pathetic. When it is realized that many of these older types began their employment in rehandling tobacco shortly after they were emancipated from slavery, it can be readily understood that there would be this blind submission to authority however kind or tyrannical. Although the heart has registered its accord with or revolt against conditions which have surrounded these pioneer workers, they have known no other course than to give to industry the best that they could, in prayer and belief that the best would come back to them.

The employer who has grown old in his factory is also characteristic of the tobacco industry in the Southland. A few of these industrial veterans remain private owners of their plants, but the majority of them have placed their establishments under the control of those large tobacco corporations which are fast monopolizing the tobacco industry. However, these pioneers remain to a large extent as managers of factories; and their antiquity and ignorance of modern industrial standards are reflected in their management. As a matter of fact, the officials of the tobacco factories in the South seem to have been for decades in a state of industrial lethargy from which they are just awakening, with naive surprise, to those standards which are essential in stabilizing industry and safeguarding the health and efficiency of the workers.

The sorely needed improvement of many old plants in the South has only been possible through expansion, for their decadence and antiquity render any remodeling impracticable. It is not unusual to find the white women workers occupying the new modern sanitary parts of the factory, and the Negro women workers isolated in the old sections which the management had decided to be beyond the hope of any improvement. Employers seem to feel that the sentiment and history surrounding these venerable building relics will counteract the lack of those factory comforts and safeguards which have been considered necessary and profitable for other women workers. Managers of tobacco factories would do well to begin to realize that sentiment of the past no longer appeals to Negro women, and that only by giving them those industrial incentives and rewards which have proved beneficial and inspiring to other human beings, can they evoke from them their heartiest and best industrial response.

Conditions of employment throughout the tobacco industry are deplorably wretched, and yet conditions for Negro women workers are very much worse than those for white women workers. This discrimination is facilitated by the distinct division in the occupations of Negro and white women workers in the tobacco industry. Negro women are employed exclusively in the rehandling of tobacco, preparatory to its actual manufacture. White women workers do not envy them this employment, nor would they submit to the conditions which it entails. Operations in the manufacture of cigars and cigarettes are performed exclusively by white women workers. Negro women workers are absolutely barred from any opportunity for employment on the manufacturing operations. The striking differences in working conditions which these occupational divisions provoke are further facilitated by the absolute isolation of Negro workers from white in separate parts of the factory buildings or else in separate buildings.

There are thousands of Negro women in the tobacco industry of the Southland today who have evolved from that old satisfied subservient type, and are cognizant and desirous of those working conditions which are conducive to efficiency and increased production, and better and more wholesome living. Industry in the South now has to reckon with this new, recreated American Negro, who feels that she deserves a woman’s chance in this “land of the free.” She is keenly aware of every condition for growth and industrial betterment which is denied her, and she experiences a distinct reaction to every discrimination which is made against her.

Tens of thousands of Negro women in the South are employed ten hours daily in old, unclean, malodorous buildings in which they are denied the most ordinary comforts of life. Either standing all day, in some occupations, or, in others, seated on makeshift stools or boxes with no back support, they toil incessantly throughout the long, tedious hours of the work day, except for a half-hour lunch period at noon.

During the intermission there is no means of securing a hot meal or of resting, and there is no alternative except to spend this short period in the workroom or on the streets. The air in the workroom is so heavily laden with fumes and dust that it is nauseating. It is not unusual to see women with handkerchiefs tied over their nostrils to prevent inhaling the stifling, strangling air.

This condition is further accentuated by the bad sanitation in the workroom, which is often unclean, and has a small space partially partitioned off which serves as the toilet room, whose only ventilation comes from the workroom. With conditions such as these a washroom or dressing room becomes a humane and paramount necessity, and yet this facility was entirely lacking in the typical tobacco factory of the South. Nor was an adequate cloak room a usual provision, for the outer garments hung on the walls of the workroom, where they were exposed to the dust and fumes which accompany any employment in rehandling tobacco–another familiar sight in the typical rehandling plant. The barrel of water to which a common drinking cup is attached by a chain is also typical of the tobacco rehandling plants which offer the principal factory employment to Negro women in the Southland.

The wages of Negro women in the tobacco industry are entirely inadequate to provide the necessities of life. The majority of women earn on an average of twelve dollars a week during the working season, which extends from September to May. This inadequacy of wages and the seasonal aspect of the work, existing simultaneously, present a vital problem to the many Negro women workers who are responsible for the support of others besides themselves. These workers, so often concentrated in the undesirable, unhealthy sections of the cities in which they live beneath the standard of comfort, health and decency, have no alternative, for they are receiving a wage far beneath the minimum which is necessary to provide the necessities of subsistence under the present day cost of living.

The efficiency and skill of the Negro woman in her work is emphasized by most managers, who seem to feel that the ability to rehandle tobacco is inherent in every Negro woman. The other problems of labor, such as irregularity and turnover, do not trouble tobacco employers, for they acknowledge that they always have a surplus of labor on hand. The employer in the tobacco industry is so strongly fortified that the Negro woman who has awakened to her industrial possibilities and value will have many struggles before she gets a small share of those returns which this industry owes her.

Race prejudice, that most formidable barrier, is the underlying cause of many of her industrial deprivations. It has denied her any chance for promotion to those better paying, skilled occupations in the manufacture of tobacco products. Even though employers have experimented with her in this work, and concede her extraordinary ability in making a cigar, they refuse to extend this opportunity to her.

Her efforts at labor organization as a source of protection and strength in certain tobacco centers are noteworthy, even though it will be a long time before she can do any successful collective bargaining. Employers in some centers have given evidence of their feeling that their Negro women workers are their “property,” in the methods used by them to obstruct any effort at labor organization within their plants. In other tobacco centers, employers resent organization, but they tolerate it because they know that conditions of the labor market will prevent any labor organization from functioning in the tobacco rehandling plants of the South.

The hope in a better day which is cherished in the heart of every Negro woman worker in the tobacco industry is beautifully portrayed in her patience and perseverance in working and praying for those just industrial rewards which she deserves. Her song at work, which managers of tobacco rehandling plants encourage, is no idle song. It fervently expresses that supplication, that inner and heart-felt yearning for a new industrial emancipation; that trust and belief in a brighter and better day which will come to all who work and wait.

Life and Labor was the monthly journal of the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL). The WTUL was founded by the American Federation of Labor, which it had a contentious relationship with, in 1903. Founded to encourage women to join the A.F. of L. and for the A.F. of L. to take organizing women seriously, along with labor and workplace issues, the WTUL was also instrumental in creating whatever alliance existed between the labor and suffrage movements. Begun near the peak of the WTUL’s influence in 1911, Life and Labor’s first editor was Alice Henry (1857-1943), an Australian-born feminist, journalist, and labor activists who emigrated to the United States in 1906 and became office secretary of the Women’s Trade Union League in Chicago. She later served as the WTUL’s field organizer and director of the education. Henry’s editorship was followed by Stella M. Franklin in 1915, Amy W. Fields in in 1916, and Margaret D. Robins until the closing of the journal in 1921. While never abandoning its early strike support and union organizing, the WTUL increasingly focused on regulation of workplaces and reform of labor law. The League’s close relationship with the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America makes ‘Life and Labor’ the essential publication for students of that union, as well as for those interest in labor legislation, garment workers, suffrage, early 20th century immigrant workers, women workers, and many more topics covered and advocated by ‘Life and Labor.’

PDF of issue: https://books.google.com/books/download/Life_and_Labor.pdf?id=_s09AQAAMAAJ&output=pdf