I can not imagine a better comrade to honestly present the life and politics of Daniel De Leon than Louis C. Fraina. As a teenage Fraina joined the Socialist Party before quickly moving to the Socialist Labor Party in 1910, where at only 18 he became one the Daily People’s most prolific writers. As an S.L.P. journalist he covered 1913’s Lawrence strike and was deeply influenced by the actions and politics of the non-De Leon I.W.W. Returning to Socialist Party in early 1914, where he would become a leader of its Left Wing and central founding Communist. Here, he provides us with not just a balanced appreciation of Daniel De Leon, but an introduction to the ideas and debates of his era in this obituary written for ‘New Review.’

‘Daniel De Leon’ by Louis C. Fraina from New Review. Vol. 2 No. 7. July, 1914.

With the death of Daniel De Leon, the most powerful individuality in the American Socialist movement passed away.

De Leon’s name was synonymous with revolutionary Socialism —that Socialism which rejects compromise, recognizes the social value of reform but refuses to deal in reform, and considers revolutionary Industrial Unionism as the indispensable basis of Socialist political action and the revolutionary movement as a whole. De Leon saw clearly the impending menace of State Socialism, particularly within the Socialist movement; and his whole programme was an answer to that menace.

De Leon fought sturdily and uncompromisingly for ideas now popular when these ideas met only with scorn and ridicule; nearly every American expression of revolutionary theory and action bears the impress of his personality and activity; and revolutionary unionism hails him as its philosopher and foremost American pioneer.

The National Committee of the Socialist Party in a resolution pays tribute to De Leon’s “honesty and singleness of purpose.” But De Leon’s activity was marked by more than “honesty and singleness of purpose,” although these qualities in themselves are a heroic thing in the American movement, which often seems the negation of “honesty and singleness of purpose.”

I.

Opinions of De Leon jostle each other contradictorily—a shoddy intellectual and a genius; a martyr and a scoundrel; a cheap politician and a thinker who built for the future; a man of no principle and a man who adhered too strictly to principle. The New York Volkszeitung says that De Leon died a couple of decades too late, and viciously stigmatizes him as a “destructionist,” and that alone. The Call correctly terms him “truly great,” but shows only a vague conception of his role in the Socialist movement. The Weekly People, organ of the S. L. P., praises him extravagantly as “one of the world’s greatest” and the “American Marx,” but like the Call, shows only a vague, though ecstatic, appreciation of his personality and activity. And through all these opinions runs the strain of love and hate aroused by De Leon’s peculiar personality, which colors all judgments of his career.

None deny De Leon’s great influence in the Socialist movement. Many may restrict that influence to 1890-1900; others extend it to the rise and decline of the I.W.W. The claim that this influence was wholly or largely pernicious ignores the movement in which it functioned, and smacks too much of the theological to deserve serious consideration. The Devil was painted wholly black in ages past. Milton realized that Satan was infinitely superior to the celestial hierarchy that fawned upon its Master.

The small movement that circumscribed De Leon’s activity developed the Caesarian spirit of preferring to be first in a small Alpine village to second in Rome. It narrowed his mind and ideas, producing the anomaly of a relatively small achievement in comparison with his tremendous capacity; and prejudiced his ideas in the minds of many who ignore ideas which are not expressive of a large movement. And yet De Leon’s contribution to the American movement bulks large—large in itself, and larger still in comparison with the contribution, chiefly negative, of others.

De Leon was the first American Socialist to insist that the American movement adapt itself to the conditions of American life—Americanize itself, not in any jingo or opportunistic sense; but in the spirit dictated by Marxism, that is, economic and political necessity.

American Socialism has been unfortunate in its theoretical and tactical aping of the German Social Democracy. The early American Socialists missed the significance of the spirit of the German movement, that you must not alone vision your ultimate ideal, but must adapt yourself to immediate conditions and grapple with those conditions. This is the first principle of Socialist politics, which the German movement has put into practice. But the early American Socialists saw a large movement developing in Germany, and concluded that German methods were just as potent in America. The German movement was invariably hurled at De Leon’s head whenever he argued on the basis of American conditions.

Early in its career the German Social Democracy adapted the general principles of Socialist political action to the special German conditions. It was wise strategy. Germany was not ripe for proletarian revolution; its bourgeois revolution had been left uncompleted; and the Social Democracy in its practical activity concerned itself with establishing bourgeois democracy and bourgeois reforms. De Leon accordingly concluded that its tactics could only remotely affect the American movement, which had no bourgeois revolution to complete. The United States is unique, politically, in having no remnants of feudalism; unique, economically, in being capitalistically the most developed; Americans have different traditions and a different psychology from Europeans. And De Leon sought to adapt theory and tactics to these conditions. I remember an editorial review of Gustavus Myers’ History of the Great American Fortunes, in which De Leon praised Myers highly, not alone for the merit of his work, but because it dealt with American conditions. De Leon had nothing but scorn for those Socialist “writers” who are perpetually rehashing the fundamental theory of Socialism as laid down with sufficient clarity by men abler than themselves.*1

De Leon’s first application of his theory was to lay particular emphasis upon the class struggle and revolutionary unionism.

The Socialist movement in 1890 was a weak thing. It oscillated between Anarchism and Populism, seemed to have no conception of the class struggle, and was living and fighting the problems of the European movement. It needed a dominant personality and emphasis on the class basis of the movement. De Leon supplied both. The propaganda of class consciousness and class action was not so difficult in Europe as in America, and required less moral courage. In Europe class divisions were generally recognized and accepted; while in America fluid class conditions, free land and a pervasive bourgeois ideology obscured the class struggle, making its theory and practice all the more necessary. And De Leon hammered upon the idea of class struggle until it became part and parcel of the movement, resulting in uncompromising political action. This service can never be underestimated. In our peculiar American conditions it constitutes a greater achievement than similar services in any European country.

As a corollary to this, De Leon insisted upon revolutionary unionism, an insistence which crystallized into the Socialist Trade and Labor Alliance. And here the fight started. The reactionaries pointed to Germany and said, “We must co-operate with the trades unions.” De Leon answered, “But in Germany the unions came after the political movement, and were largely built up by the Social Democracy. While here the unions are notoriously reactionary and corrupt.” Different conditions dictate different tactics. De Leon and the S.L.P. acted accordingly,—fought the unions and organized opposition unions. Was the S.T. & L.A. premature? Undoubtedly; but so was the old International premature; you must start somewhere: and pioneer work is indispensable.! Yet the S.T. & L.A. prepared the way for the American Labor Union and the I.W.W.—both premature and both necessary. These experiments have yielded valuable experience and a philosophy of revolutionary unionism.

At the S.T. & L.A. period, De Leon’s conception of revolutionary unionism was pro-political. He still had the old Socialist theory that the political movement must dominate the unions, as in Germany. (Later De Leon reversed himself, and correctly conceived the political movement as pro-industrial; that is to say, revolutionary unionism must dominate the political movement.) At this period De Leon projected revolutionary unionism as an auxiliary of the political party, ascribing to it no decisive revolutionary mission. The S.T. & L.A. was largely a weapon to fight conservative A.F. of L. politics. The friends of the A.F. of L. roared in protest; and, as the Volkszeitung said ten years later, split the Socialist movement to save the A.F. of L.

This is significant: and the councils and policy of the Socialist Party have since its inception been dominantly molded by the A.F. of L. and the Aristocracy of Labor. This was just the eventuality De Leon feared and fought against. And at this period De Leon’s revolutionary unionism was largely a means to prevent the Socialist political movement being controlled by the Aristocracy of Labor and the Middle Class—two social groups which, De Leon showed time and again, have certain interests in common and against the revolutionary proletariat.2

And there surely is no better way of holding a Socialist party true to its revolutionary mission than by insistence upon revolutionary unionism—an insistence which is bound to alienate the Middle Class and Aristocracy of Labor. A Socialist political party must favor revolutionary unionism and actively propagate its tenets. There is not—in the very nature of things there cannot be—any such thing as “neutrality toward the unions.” The Socialist Party’s “neutrality” has ended in its swallowing the principles of the A.F. of L., and getting in return the support of the A.F. of L. machine—for the Wilson-Bryan party. The political movement is not a political party alone: it is the political phase of the revolutionary movement as a whole: and if revolutionary unionism is a necessary, an indispensable, factor in the revolutionary movement, the political party must incorporate revolutionary unionism in its propaganda.

There is another vital reason for revolutionary unionism: it is the only adequate answer to the menace of State Socialism. De Leon early saw the impending dangers of State Socialism, and grappled with the dangers. His opposition to the Socialist Party was fundamentally caused by its State Socialist aspirations—its propaganda of reformism and government ownership making for State Socialism or State Capitalism, in the interest alone of the Middle Class and the Aristocracy of Labor. De Leon originally fought this danger by insisting upon rigid class action and “no reform” politics, though still holding to the theory that control of the State was the way to revolution. But this in itself was insufficient. As long as control of the State is considered the only way to revolution, State Socialism is inevitable; you must have another agency outside the State to perform the revolutionary act. And De Leon, seeing this clearly in course of development, solved the contradiction by reversing his old position, and emphasizing the mission of Industrial Unionism as the means for the revolutionary act—the overthrow of Capitalist Society and its State.

De Leon’s espousal of Industrial Unionism and the I.W.W., and his development of an industrialist philosophy of action, constitute his crowning contribution to American Socialism. While he had no part in the conference which called the 1905 convention, De Leon was the dominating power in the convention itself, am for two years in the I.W.W. Impartial observers of the convention, like Paul F. Brissenden, have attested De Leon’s supremacy of ideas and personality, as De Leon and his co-delegates of the S.T. & L.A. were in a very small minority.

Many factors united to disrupt the I.W.W. There was the financial panic of 1907, the dishonesty of officials, which appears at the early stage of all revolutionary movements, and the conflicts over political action. The chief factor was the fight over a revolutionary conception of Industrial Unionism and a conservative conception—a fight between the unskilled and the skilled. The I.W.W. at the start tried to bridge the gap between the two, and failed; and now the Haywood-St. John I.W.W. is trying to build exclusively upon the basis of the unskilled. Revolutionary Unionism at this stage must depend upon the unorganized and the unskilled.3 De Leon’s fight for political action in the I.W.W. was the cause of his being thrown out of the organization in 1908. It is a fight which will have to be fought again. Socialist Party timidity is creating a strong anti-political sentiment with which the movement will have to reckon. And De Leon’s insistence upon political action shows his broad conception of the revolutionary movement.

De Leon’s activity in the I.W.W. was inspired by the following clear-cut conception of revolutionary action:

1. Industrial Unionism, organized in harmony with the mechanism of concentrated capitalist production, is the condition sine Qua non of the revolutionary movement. Mere industrial unionism,however, is insufficient: it must be revolutionary industrial unionism.

2. By means of the industrial organization, the workers can secure all the immediate betterments they require—immediate reforms which, gained by means of the power of the workers through mass strikes, constitute steps toward the final goal, develop the integrity and self-reliance of the proletariat, and prepare it for its historic mission.

3. The movement should not deal in political reform. Reforms of this character benefit the Middle Class and the Aristocracy itself—a theory now being proven by capitalist Progressivism. Political reform is a menace to the integrity of the revolutionary movement.

4. The Socialist political movement is purely agitational; its mission is not “constructive politics,” but to lash onward the bourgeois parties by an aggressive policy, warm into life the revolutionary spirit of the workers, and courageously develop the necessary sentiment for revolutionary Industrial Unionism. Only upon this basis is political action justifiable.

5. The goal of the revolutionary movement is the overthrow of political government, which means the overthrow of all class rule—the substitution of industrial representation for territorial representation, industrial administration for political government. Industrial Unionism not only organizes for the immediate, every-day struggles of the proletariat, but prepares the structure of the future society, organizes the Socialist State within the Capitalist State, ready to assume control of society. In other words, the revolutionary act will be performed by the industrially organized proletariat; and Industrial Unionism will not only be the most powerful force in overthrowing Capitalist society but will constitute the basis of the Socialist society of the future.

It is obvious that this theory of the Revolution can be potently when State Socialism is dominant. The Capitalist State is not yet bankrupt; it still has a mission to perform—the concentration of government control over industry and society, the development of a monstrous bureaucracy which will make the overthrow of political government imperative, exhausting the benefits of purely political reform, and clarifying class lines. De Leon faced the menace of State Socialism; when the movement faces the reality it will be compelled by necessity to organize itself industrially for the overthrow of political government

There is another corollary which De Leon only vaguely adumbrated, the necessity of placing revolutionary emphasis upon the unskilled. De Leon’s merciless attacks upon the Aristocracy of Labor, his scorn of mere reforms, his belief in the increasing misery of the workers (true only of the unskilled), and his whole philosophy show that he saw the necessity of building upon the organization of the unskilled, but he never clearly formulated this theory, and did not sufficiently emphasize the role of the unskilled.

It was De Leon’s great achievement that, in spite of the limitations of his period, he saw clearly ahead and projected a program which not only has immediate value but which becomes indispensable in the very near future.

II.

De Leon’s fight for Revolutionary Socialism met with the temporary defeat of similar fights elsewhere. Revolutionary Socialism has in all lands been pushed to the wall; reformism is now in the ascendant in the international movement.

It was a fight against the temporarily inevitable. Was the fight, then, useless? Not at all. It did an indispensable pioneer work; it laid the basis for a successful fight later on; and it has given the American movement an inspiring revolutionary tradition.

Asking no quarter and giving none, De Leon fought as uncompromisingly for these ideas with a small group of followers as with a strong organization at his back. Men mattered little to him: ideas were the chief thing.

This emphasis on ideas and neglect of men was a serious flaw in De Leon’s make-up. Herein he was typical of the old school of Socialists, who acted on the belief that the movement had to deal mainly with social forces, individual influences being of only slight importance. They neglected individual psychology, assuming that for all practical purposes it was sufficient to know that the social milieu conditions psychology. But that is not sufficient. White socially conditioned, individual psychology nevertheless becomes an independent factor in the social process as a whole, obedient to laws and motives of its own: laws and motives which men engaged in organizing human forces must comprehend if they desire success. De Leon was not a psychologist: he misunderstood men and motives; and his wrong judgments of men often led him to harsh measures, rousing unnecessary antagonism.

Perhaps even more important was another serious flaw. While thoroughly honest in his ultimate purposes, never seeking a personal advantage unless he thought it in the interest of the movement, De Leon was sometimes dishonest in his methods of attack. He was temperamentally a Jesuit, consistently acting on the principle that the end justifies the means. And he attacked opponents with all the impersonal implacability of the Jesuit. These methods crushed opponents and drove men of ability out of the S.L.P.; while a suggestion of Cagliostro in his personality developed the fanatical loyalty of a sect.

It is an error to conclude, however, that De Leon’s personality and methods were responsible for the decline of the S.L.P. Other Socialists have had the identical faults and succeeded in their ends. There were other and more fundamental factors involved.

De Leon’s uncompromising conception of the revolutionary movement was an obstacle to a large party being organized. The many non-proletarian economic groups in revolt slowly gravitating toward Socialism, and the immaturity of the proletariat, have made impossible as yet a revolutionary party as conceived by De Leon. Accordingly, revolutionary ideas at this stage are potent only within a large and broad movement, as an educational force; not as the basis of an independent movement.

The S.L.P. ignored the psychology of struggling workers; its propaganda was couched in abstract formulas; just as its sectarian spirit developed a sort of sub-conscious idea that revolutionary activity consisted in enunciating formulas. This sectarian spirit produced dogmas, intemperate assertions, and a general tendency toward caricature-ideas and caricature-action; and discouraged men of ability from joining the S.L.P.

De Leon was not a “destructionist”; his ideas were premature; the limitations of his period hampered him; and you cannot call a man in the clutch of these circumstances a “destructionist.”

And having considered these defects of De Leon’s character, just a few words about his truly noble traits.

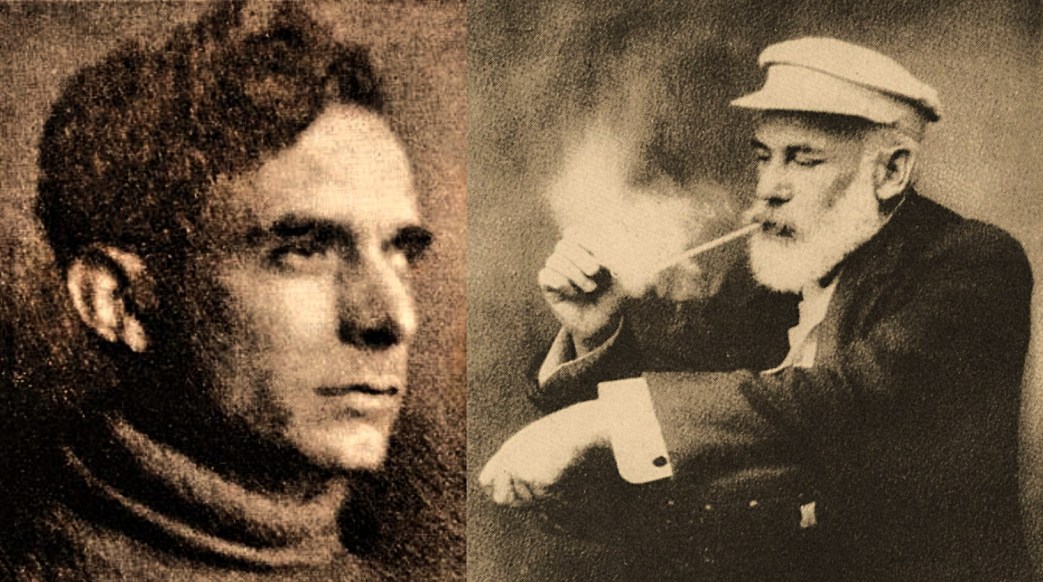

His personality was vivid, compelling, constituted to arouse active love and active hate. His thorough honesty and great sacrifices for the movement are an inspiring thing, and the power and nobility of his inner character were suggested in his outward appearance.

His bearing was powerful, dominant, his appearance magnificent. His short neck was sunk in between drooping shoulders, above which towered a massive white head, worthy of posing for a Rodin “Thinker.” His imaginative forehead rose in a curve and described a semi-circle with the back of a perfectly-shaped skull. In contrast with the backward curve of the rising brow was the forward projection of cheek bones and chin, characteristic of his aggressive personality. The wiry mustache and beard, protecting a firm, amorous mouth, emphasized the power of a strong face, serene in its intensity and intense in its serenity. In the corners of his deep-set piercing eyes lurked a laughing, mischievous twinkle, full of a humanity which often broke through his reserve, lighting his face with a human glow which made you expand in its delicate warmth. The only defect of that truly unique face was a big, vicious nose.

De Leon dressed shabbily—from necessity. Yet he had the artist’s love of good clothes. A comrade one evening entered his office, dressed for a social function. De Leon complimented her on her pretty dress. “Oh, a trifling vanity of the flesh,” she answered, lightly. “Ah, no,” replied De Leon. “You say that out of regard for me: my own clothes are so shabby.”…”That man,” said a friend of mine, “though clad in rags, would still be the aristocrat.”

And this aristocrat—with pink skin, delicate hands and cultured ancestry—broke completely with his class to devote himself to Socialism. All his former connections were severed: his old world ceased to exist for him. The man was too big, too earnest, possessed of too much depth of feeling, to take an academic interest in Socialism: as a member of the Socialist Labor Party, De Leon became Wholly identified with the movement. This fiery sincerity and intolerance of half measures were typical of De Leon’s whole activity.

Socialists of to-day can hardly realize the courage and character expressed in this action. The Socialist movement twenty-five years ago was an insignificant thing: it was not important enough to attract intellectuals. De Leon was a lecturer on international law at Columbia University: openly to avow himself a Socialist was to lose caste with his associates, inviting ridicule and contempt; actively to identify himself with the movement was to be thrown bodily out of the university. All his brilliant prospects of a truly great academic career he thrust aside; left it all for a movement in the making. Nor did this mean sacrificing a career alone. It meant a complete change in life, in habits, in methods of thought—a temperamental revolution. It meant giving up the common comforts of life—frugality instead of good living; Avenue “A” instead of the Upper West Side; poverty of the worst sort for a man accustomed to comfort, and with a family to support.

A year before his death De Leon was offered a good position with a prominent firm of lawyers dealing in international law, and contemplated resigning as editor of the People. He was old, sixty-one years old; poverty was acute; and his children needed an education: “I have sacrificed myself; I have sacrificed my wife; but have I the right to sacrifice my children?” His friends dissuaded him. De Leon, as editor, received a salary starting at $12 a week and ending at $30 a week; yet at his death the S.L.P. press owed him $3,500 back salary! And he never received a cent for his lectures, agitation tours, and scores of translations.

De Leon never complained. He suffered; suffered silently. Never a bitter word; never a regret; smiling activity was his answer to adversity. The Revolution was worth it all! Truly, the man was a heroic figure.

NOTES

1. Morris Hillquit, in his “History of American Socialism ” asserts that the split in the movement in 1899 was due to the efforts of his own group to throw off the German domination of the party. As a matter of fact, the Hillquit group of seceders was overwhelmingly German; while De Leon had the English organization, the majority, staunchly behind him. Hillquit and Berger have consistently introduced into our movement all the vices and none of the virtues of the German Social Democracy. De Leon was essentially a pioneer in a pioneer movement; but he scarcely realized this pioneer character of his ideas and activity. Had De Leon realized this limitation, his acts would not have been so hasty, impatient, often intolerant. Tact and patience, pliability and not rigidity, should be the distinguishing characteristics of the pioneer. De Leon saw things loom large-in a state of crisis, and acted much as if he were in the midst of the Revolution with a powerful movement at his back.

2. De Leon was the first Socialist in America whose Socialism was Marxist in spirit. He was a brilliant Marxist, and his principle of “Americanizing” derived less from study of American conditions than from his grasp of the Marxian method. In this Americanizing process, De Leon neglected a few important factors subsidiary to the fundamental factors which he grappled with. He ignored the problem of the backward South and the subjection of the Negro. He failed to tackle the problem of the American judiciary, the usurped powers of which menace democracy. He seems never to have realized the importance of a national system of labor legislation in America, which would not only improve the workers’ living conditions, but the struggle for which would impart new unity and impetus to the labor movement. These last two things have been taken up by the Roosevelt Progressives in a conservative manner and for a conservative purpose subsequent to the agitation of Herman Simpson, who, while editor of the New York Call, grappled with these problems in a Marxian, that is, revolutionary manner, seeking to make the Socialist Party drive forward the bourgeois progressives, instead of trailing in their rear. A. M. Simons’ efforts to “farmerize” the Socialist Party are non-revolutionary and non-proletarian “Americanizing”— making concisions to farmers and Middle Class.

3. Another factor was the desertion of Socialist Party men, such as Ernest Untermann, A. M. Simons and Eugene Debs; Simons and Untermann being disgruntled at De Leon’s supremacy, and Debs being unwilling to face the issue of the bitter internal fight. As an instance of the methods used in attacking De Leon, I may mention Simons’ charge in committee that De Leon was a police-spy and should be denied admission to the convention. De Leon was sometimes- abusive and intolerant in attack, but he never went as far as his opponents, and often retracted, as in the case of Wayland and Ben Hanford. De Leon was not the intolerant bigot decried by his enemies; one instance in proof being his praise of the NEW REVIEW, although representing a different tendency from his own.

The New Review: A Critical Survey of International Socialism was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. Bases in New York it declared in its aim the first issue: “The intellectual achievements of Marx and his successors have become the guiding star of the awakened, self-conscious proletariat on the toilsome road that leads to its emancipation. And it will be one of the principal tasks of The NEW REVIEW to make known these achievements,to the Socialists of America, so that we may attain to that fundamental unity of thought without which unity of action is impossible.” In the world of the East Coast Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Robert Rives La Monte, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Arturo Giovannitti, Harry W. Laidler, Austin Lewis, and Isaac Hourwich as editors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 and lead the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. International writers in New Review included Rosa Luxemburg, James Connolly, Karl Kautsky, Anton Pannekoek, Lajpat Rai, Alexandra Kollontai, Tom Quelch, S.J. Rutgers, Edward Bernstein, and H.M. Hyndman, The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable and invaluable archive of Marxist and Socialist discussion of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1914/v2n07-jul-1914.pdf