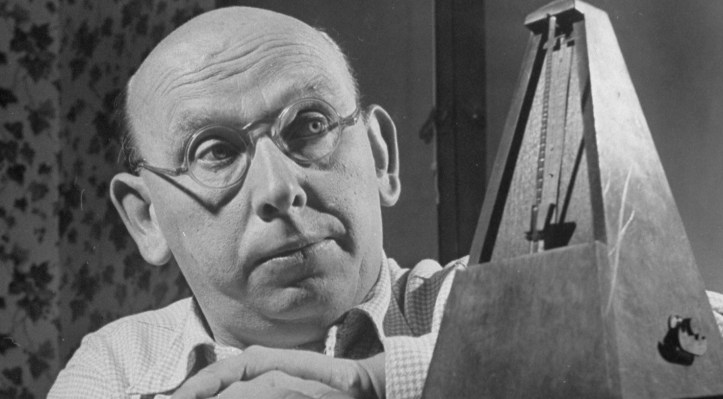

From fellow avant-garde musician Marc Blitzstein this fantastic review of Hanns Eisler’s The Crisis in Music would inspire Blizstein’s to write his own music manifesto. A year after this was written, Blizstein’s collaboration with Orson Welles, The Cradle Will Rock, was barred from showing for its radical politics. Gifted and prolific, Blitzstein was called before HUAC where he admitted his past Communist Party membership and refused to give names or cooperate. A gay man, Blizstein was killed in an alleged homophobic attack in 1964.

‘Hanns Eisler: A Music Manifesto’ by Marc Blitzstein from New Masses. Vol. 19 No. 13. June 23, 1936.

ON December 7, 1935, Hanns Eisler made a short speech. It was part of a symposium called “Music in the Crisis,” given at Town Hall. Others spoke, performed: Copland, Cowell, Oscar Thompson, Mordecai Bauman, the New Singers. When Eisler had finished it became suddenly clear to composers and musicians in the audience that here was a way for music in the present social conflict; an authentic, exciting, possibly complete plan projected. The translation was inadequate; speeches anyway are worrying, they give off impressions of trickiness and brilliance, one hopes the real words are real facts but one isn’t secure. The speech has now been issued as the first of a series to be brought out by the Downtown Music School, where Eisler is a faculty-member. It is a neat, handsome pamphlet: the translation is excellent. And it turns out that the words are facts.

One might have known it. For there are Eisler’s other facts: the two masterworks “Massnahme” and “Mother;” the polyphonic choruses “Ueber das Toeten,” “Auf den Strassen zu Singen,” “Liturgie vom Hauch;” the mass-songs “Forward” and “Rise Up;” the film Kuhle Wampe. Eisler is first a composer; it is good to remember that his formulation, his theories grow out of, have roots in, music. They are your true “esthetic,” articulated out of the thing, possessed and actual, not cooked-up, not arbitrary, not nursed along to induce the thing, and make it happen. Schoenberg once said of the typical theorizer, that “nobody watches more closely over his property than the man who knows that, strictly speaking, it does not belong to him.” Eisler’s property is his own; he shares it with the working class of the world.

For Eisler is more than a composer. Rather, he is the new kind of composer, whose job carries him to the meeting-hall, the street, the mill, the prison, the school-room and the dock. Concert-hall, opera-house, theater are still in the picture; but the artist is not only artist but worker, his responsibility to all workers shows itself in all his work. Eisler is a Marxist. Other composers have been, are, Marxists; Eisler is possibly the first instance of the real fusion of Marxist and musician. His work in pre-Hitler Germany and in the post-Hitler outside world has been a wedding of music and dialectics; he is a leader as Gorky is a leader; he has experienced deeply the life and problems of the working class, his thought propels him to music and to action. Sometimes the action is the organizing of a music-front; sometimes it is the formation of a class of young composers; sometimes it is the music itself, or the teaching of socialism, through the clear, light, wiry structure of the Lehrstuck, which he created with Brecht.

Now for the pamphlet. After an introduction there are ten “theses;” each exposes a proposition tersely, with no extensions or elaborations; each opens up a light. First, the existing state of music: undoubtedly produced as a luxury. When misery increases in such proportions as today, this luxury takes on the character of provocation. What else can we think of Stravinsky’s “Apollon Musagète” ballet, with its suave, dry, elegant maneuvers, its French-court nymphs and gods, its heavy sheen of strings, its sleek loveliness (for the music is really lovely, really beautiful, if it could be cut off from the whole picture)? What else can we think of Markevich’s “Psaume” or Hindemith’s “Marienleben” or Roger Sessions’ “Choral Preludes?” Or of chamber-music concerts, or platinum-studded operas and opera-balls, or hothouse virtuoso conservatories?

Then the situation of composers; ivory-tower, wish-fulfillment artists, “dealers in narcotics” against their will or without their knowledge. This is a hard nut for composers to crack; we have for so long dwelt in the high reaches of “art” atmosphere, believing patrons and entrepreneurs, that we are the anointed and the insulated, that it isn’t nice to realize we are the tool of a vicious economic setup. The unconscious (sometimes not so unconscious) prostitution of composers in today’s world is one of the sorry sights to see. It inheres all along the line, from the most successful to the never-heard; even when we starve, we think of it as a poetic “upper-class” starvation, quite different from the starvation of the ordinary unemployed worker. It is about time we discovered where our allegiance lies.

Thesis V begins the positive aspect; the situation creates organizations “among the most advanced sections of the proletariat” devoted to the participation of music in the “struggle for the radical change of the capitalist order of society;” for “the crisis in music can only be overcome insofar as music itself takes part in the liquidation of the worldwide social crisis.” There is a deep-seated reluctance in musicians to change their ways; something in the special training music requires seems to engender a defensive, aggressive, reactionary attitude. The insurgents of “modern music,” with their innovations in technical craft, found that out; now that the very purpose of music is in question, the resistance is, even greater. But here is where even left-wing musicians haye faltered or faced a blank, saying, “Yes, but how?” Here is where Eisler presents the plan. Thesis VII is a double column, headed “For the Old Purpose” and “For the New Purpose.” Then a list: medium, idiom, style, forms, are covered. For the old purpose, “predominance of Instrumental Music;” for the new, “predominance of Vocal Music.” This idea is already predicated in the recent history of music, when the epochal instrumental forms of the Fugue and the Sonata were succeeded by the Wagnerian Music-Drama, a composite vocal-and-instrumental music. “The trend no more means the death of instrumental music, than the growth of the orchestra meant the death of chamber-music.” Some other samples: on the left side, “Songs: performed by a specialist in the concert hall before passive listeners. Subjective-emotional in mood;” on the right, “Mass Song, Song of Struggle: Sung by the masses themselves on the streets, in the work shop, or at meetings. Activizing.” It is probably more accurate to speak of the Mass Song as a new short form, not necessarily replacing the concert-song, for which there is still a big field; Eisler’s “In Praise of Learning” and Siegmeister’s “Strange Funeral” are cases in point. The ballad, the new Opera and Operetta, the Lehrstuck differ from the old Ballad, old Opera and Operetta, and the Oratorio by the social criticism of the texts, and, in the music, a destruction of conventional effects and an interspersing of ironic comment and quotation. This does not imply an exclusive dependence on satirical music; the whole of Mother is “straight,” a positive expression of a philosophy; nor is it heavy, nor effusive, nor always loud and fast.

The list goes on. (“The Composer: as a personality. Individual Style;” and then, “The Composer: as a specialist, mastering several styles of composing.”) The pamphlet is perhaps too short, too cryptic, like an outline of the volume the subject demands. It is also possible that one may disagree with or want to modify this or that point. In a sense it is personal, although for a composer of Eisler’s originality I find it amazingly objective. It is not all his invention; some of it has been known, tested in the Soviet Union; some of it (theater-music, for example, as an “independent element, as a musical commentary”) is the product of contemporary musical thinking, stemming from Stravinsky, the Six, and others. But the correlation, the impetus, the direction are Eisler’s. He has presented a method, a scaffolding and framework any world-minded composer can adapt to his needs; more, it is the plan he must in some way follow. When Eisler finally says: “To the criteria of ‘Invention,’ ‘Technical Skill,’ ‘Emotion,’ the decisive criterion of the ‘Social Function’ must be added,” it is plain, no idle or rhetorical thing is being uttered; in the phrase the whole conception is summed up. I don’t want to mince words; I think that this little essay is very possibly the manifesto for the revolutionary music of our time.

The Crisis in Music. Hanns Eisler. Published by the Downtown Music School, 214 E. 15th St., N.Y.C. Price, 10 cents.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1936/v19n13-jun-23-1936-NM.pdf