The next section of Kautsky’s 1908 work as translated by Ernest Untermann looks at Marx’s relationship with Chartism and Blanquism.

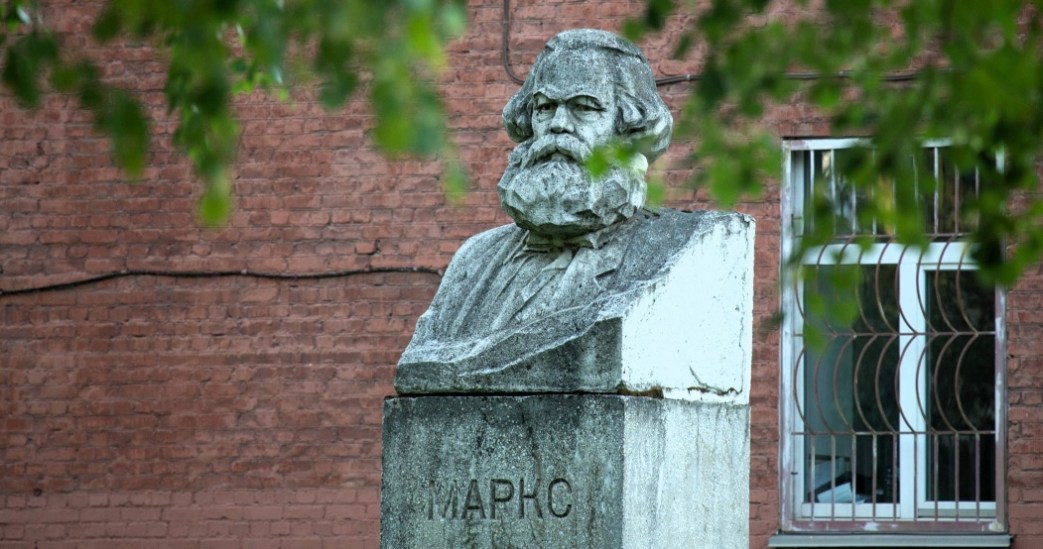

‘The Historical Achievement of Karl Marx: Unification of the Labor Movement and Socialism’ by Karl Kautsky from The Socialist (Seattle). Vol. 8 Nos. 377. May 30, 1908.

The materialist conception of history marks by itself an epoch. With it begins a new era of science, in spite of all reluctance of bourgeois learning. It marks an epoch, not merely in the history of thought, but also in the history of the struggle for social evolution, of politics in the widest and highest meaning of the word. For by means of it the unification of the labor movement and of Socialism was accomplished and the proletarian class struggle endowed with the greatest strength of which it is capable.

The labor movement and Socialism are by no means identical from the outset. The labor movement arises, with necessity of itself as a resistance against industrial capitalism, wherever this appears, expropriates the laboring masses, oppresses them, but at the same time crowds and unites them in large enterprises and industrial cities. The most primitive form of the labor movement is the purely economic one, the struggle for wages and labor time, which at first assumes merely the form of simple outbreaks of despair, or unprepared revolts, but is soon carried over into higher forms by labor organization. Along with it appears at an early stage the political struggle, The bourgeoisie itself requires in its struggles against feudalism the help of the proletariat and calls upon it for that purpose. In this way the laborers soon learn to value the significance of political freedom and political power for their own purposes. Particularly universal suffrage soon becomes in England and France the objects of the political efforts of the proletarians, and leads in England, during the thirties, to the formation of a proletarian party, the Chartists.

Socialism arises even before that time. But by no means among the proletariat. True, it is a product of capitalism, just as the labor movement is. Like the labor movement, socialism arises from the desire to escape the miseries, which capitalist exploitation brings upon the laboring classes. However, the resistance of the proletariat arises of itself in the labor movement, where a large laboring population congregates, whereas socialism requires a deep insight into the nature of modern society. All socialism rests upon the understanding, that capitalist misery cannot be abolished so long as bourgeois society lasts, that this misery rests upon the private property in means of production and cannot disappear until it does. Upon this point all socialist systems agree. They differ only about the ways that should be chosen for the purpose of abolishing this private property, and in their conceptions of the new social property that is to take its place.

Although the expectations and suggestions of some socialists were at times rather naive, yet the understanding, upon which they were based, required a social science that was wholly inaccessible to the proletariat during the first decades of the nineteenth century. It is true that a man could arrive at socialist understanding only when he placed himself upon proletarian ground and looked at bourgeois society from this point of view. But at the same time it had to be a man who commanded the means of science, which was then even more than at present accessible for bourgeois circles only. Even though the labor movement develops naturally and inevitably out of capitalist production wherever this reaches a certain height, socialism required for its development not merely capitalism, but also a meeting of extraordinary circumstances, such as occurred but rarely. In any event, however, socialism could have its first beginning only in a bourgeois environment. In England, until very recently, socialism has even been mainly propagated by bourgeois elements.

This fact might appear in contradiction with the Marxian theory of the class struggle. But it would be so only, if the bourgeois class had ever adopted socialism anywhere, or if Marx had declared it to be impossible that single non-proletarian individuals could, from particular motives, accept the point of view of the proletariat.

Marx has always contended no more than that the working class is the only power which can consummate socialism. In other words, the proletariat can free itself only by its own power. But this is by no means equivalent to saying that only proletarians can show it the way to that goal.

That socialism does not amount to anything, unless it is backed by a strong labor movement, need not be proved any more today. Not so clear is the reverse side of the medal, namely that the labor movement can develop its full power only, when it shall have understood and accepted socialism.

Socialism is not the product of ethics standing outside of time, space and all class distinctions. Fundamentally and primarily it is the science of society from the point of view of the proletariat. But science serves not merely for the satisfaction of our curiosity and inquisitiveness in trying to understand the unknown and mysterious, it also has an economic aim, namely that of saving energy. It makes it possible for men to find their way more easily through reality, to apply their strength more efficiently, and thus to perform and accomplish at all times the maximum of the work possible under the existing circumstances. In its points of departure science serves directly and consciously such purposes of saving energy. The more it develops and departs from its starting point, the more intermediate links come between its exploring activity and its practical effects. However, the connection between the two can merely be obscured, not abolished thereby.

Thus the proletariat’s science of society, socialism, serves to make possible the most effective application of its strength and thus the highest development of its powers. This science accomplishes this so much better, the more perfect it becomes itself, the deeper its understanding of the reality opened up by it.

Socialist theory is by no means an idle play of parlor scientists, but a very practical thing for the fighting proletariat.

Its principal weapon is the combination of its total mass in powerful and independent organizations, free from all bourgeois influences. This it cannot accomplish without a socialist theory, which alone is able to discover the common proletarian interest in the varied multiplicity of the different proletarian strata and to separate them all sharply and permanently from the bourgeois world.

This cannot be accomplished by that naive labor movement, which arises of itself among the laboring classes against the increasing capitalism, and which is devoid of every theory.

Take a look, for instance, at the labor unions. They are organizations of trades, which seek to protect the immediate interests of their members. But how different are these interests in the individual trades, how different those of the seamen from those of the coal miners, those of the cab-drivers from those of the typesetters! Without a socialist theory they cannot recognize the identity of their interests, without it the various strata of proletarians face one another as strangers, or even as enemies.

Since a labor union defends only the immediate interests of its members, it is not, merely for that reason, antagonistic to the whole bourgeois world, but primarily to the capitalists of its own sphere. Apart from these capitalists there are other bourgeois elements, who derive their existence directly or indirectly from the exploitation of proletarians, and who are thus interested in the bourgeois order of society and will oppose every attempt to make an end of proletarian exploitation, but who have no interest at all in having labor conditions in that particular line very bad. Whether a spinner of Manchester earned 2 shillings or 2 shillings per day, whether he worked 10 or 12 hours per day, would be immaterial to a great landlord, a banker, a newspaper owner, a lawyer, so long as they didn’t own spinning stock. Such people might be interested in making concessions to labor unionists, in order to obtain in return their services in politics. In this way it became possible that labor unions, which were not enlightened by a socialist theory, could be made to serve ends that were anything but proletarian.

But even worse things were possible and happened. Not all proletarian strata are able to form labor organizations. The distinction between organized and unorganized laborers arose. Wherever the organized laborers are filled with socialist thought, they become the most vigorously combative sections of the proletariat, the champions of their entire class. Where they lack this thought, they are prone to become aristocratic, to lose not alone all interest for the unorganized laborers, but to place themselves frequently in opposition to them, to make their organization difficult, and to monopolize the benefits of organization. The unorganized laborers, on the other hand, are incapable of fighting, of rising, without the help of the organized laborers. Without the assistance of these they sink into poverty so much the more, the higher the organizations rise. In this way the organized labor movement, in spite of the increasing strength of some proletarian strata, may bring about a direct weakening of the entire proletariat, unless the organizations are imbued with the socialist spirit.

Neither can the political organization of the proletariat develop its full power without this spirit. This is plainly shown by the first labor party, the Chartists of England, born in 1835. It is true, that Chartism contained some very far-reaching and farseeing elements, but in its totality it followed up no definite socialist program. It had only some practical aims, which were directly obtainable, above all universal suffrage, although this was not supposed to be an end in itself, but a means to an end; but the end, for the Chartists as a body, consisted only in some immediate economic demands, particularly the normal Ten Hour Day.

The first disadvantage of this was that the party did not become a pure class party. Universal suffrage was a thing which interested also the little bourgeois.

Some may think that it would be an advantage, if the small bourgeois as such would join the labor party. But this would make this party only more numerous, not stronger. The proletariat has its own interests and its own methods of fighting, which differ from those of all other classes. It is hemmed in by uniting with other classes and cannot develop its full strength. It is true, that we socialists welcome small business men and farmers, if they wish to join us, but only on condition that they place themselves upon proletarian ground and feel like proletarians. Our socialist program is a guarantee that only such small business and small farmer elements will join us. The Chartists did not have such a program, and for this reason numerous little bourgeois elements joined in their struggle for universal suffrage, who little understood and sympathized with proletarian Interests and methods of fighting. The natural consequence of this were hard internal fights within Chartism, which weakened it considerably.

The defeat of the revolution of 1848 made an end, for a decade, to all political labor movements. When the European proletariat began to stir once more, the English laboring class again took up the fight for universal suffrage. A resurrection of Chartism was to be expected.

But the English bourgeois class then made a master stroke. It split the English proletariat, granted to the organized laborers the suffrage, detached them from the mass of the other proletarians, and thus prevented a rebirth of Chartism. This movement did not have a comprehensive program beyond universal suffrage. As soon as this demand was fulfilled in a way that satisfied the combatant portion of the laboring class, the bottom fell out of it. It is only in our own day that Englishmen, painfully dragging behind the laborers of the European continent, devote themselves to the formation of an independent labor party. But even now many of them have not grasped the practical significance of socialism for the full development of proletarian power, and refuse to adopt for their party a program, so long as this could be only a socialist one. They wait until the logic of fact forces such a program upon them. Only when the new labor party shall be fully imbued with socialist understanding, will the labor movement of England develop its full power and be able to produce the best fruit. In our day the prerequisites for the indispensable union of the labor movement with socialism exist everywhere. In the first half of the nineteenth century they were missing.

In those days the working people were crushed by the first onslaught of capitalism, so they could hardly ward off its blows. Still they resisted in a primitive way. But they found no opportunity for deep social studies.

Under these circumstances the bourgeois socialists saw in the poverty spread by capitalism only the one side, the depressing one, not the other, the stirring and revolutionizing one, which spurred the proletariat on. They thought that there was only one factor, which could bring about the liberation of the proletariat, namely the good will of the bourgeoisie. They judged the bourgeoisie by themselves and fancied that they would find in it enough allies to carry through socialist measures.

In the beginning their socialist propaganda found much acceptance among bourgeois philanthropists. On the whole the bourgeois are not inhuman. They are touched by misery, out of which they derive no profit, and would like to do away with it. However, though the suffering proletarian excites their pity, the fighting proletarian makes them hard. The begging proletariat has their sympathy, the demanding proletariat arouses their wild resentment. For this reason the socialists found it very disagreeable, that the labor movement threatened to rob them of that factor, upon which they built most: The sympathy of the “well-meaning bourgeoisie” for the propertyless.

They regarded the labor movement so much the more as a disturbing element, the less confidence they had in the proletariat, which then consisted on the whole of a very low mass, and the more clearly they recognized the Inadequacy of the unsophisticated labor movement. So they often turned against the labor movement, to demonstrate, for instance how useless labor unions are, which wish merely to raise wages instead of combatting the root of all evil, the wage system.

But gradually a change took place. In the forties the labor movement had developed to a point, where it produced a number of talented brains, who mastered socialism and recognized that it was the proletarian science of society. These laborers knew by their own experience that they need not depend upon the philanthropy of the bourgeoisie. They recognized, that the proletariat would have to free itself. There were also some bourgeois socialists who came to the conclusion, that no reliance could be placed upon the magnanimity of the bourgeoisie. True, they did not place any confidence in the proletariat, either. Its movement appeared to them only as a destroying power, which threatened all civilization. They believed that only bourgeois intelligence could build up a socialist society, but the incentive for it they now saw no longer in compassion with the suffering, but in fear of the aggressive proletariat. They already recognized Its tremendous power and understood that the labor movement necessarily arises from the capitalist mode of production, and would grow more and more within this mode of production. They hoped that the fear of the growing labor movement would cause the intelligent bourgeoisie to deprive it of its dangerousness by socialist measures. This was a tremendous progress, but the unification of socialism and of the labor movement could not arise from this conception. The socialist laborers, in spite of the talent of some of them, lacked the comprehensive knowledge, which was required for the purpose of founding a new and higher theory of socialism, which should unite it organically with the labor movement. They could adopt only the old bourgeois socialism, utopianism, and adapt it to their requirements.

In so doing those proletarian socialists went farthest who connected themselves with Chartism or with the French Revolution. Particularly those who started from this revolution assumed a great importance for the history of socialism. The great revolution had shown plainly how important the conquest of the political power may become for the emancipation of a certain class. In this revolution, also, had a powerful political organization, the Jacobin Club, thanks to peculiar circumstances, succeeded in ruling all Paris and through it all France by a reign of terror of the small bourgeoisie that was strongly permeated with proletarian elements. And while the Revolution was still on, Baboeuf had already drawn its logical conclusions in a truly proletarian sense and attempted to conquer by a conspiracy, the political power for a communist organization and adapt it to its use.

The memory of this had never died among the French laborers. The conquest of the political power very early became a means for the proletarian socialists by which they wanted to acquire the strength for inaugurating socialism. But in view of the weakness and immaturity of the proletariat they knew no better way for the conquest of the political power than the uprising of a number of conspirators which was supposed to start the revolution. Among the representatives of this line of thought in France, Blanqui has become best known. Similar ideas were held by Weitling in Germany.

There were still other socialists who started out from the French Revolution. But an uprising seemed to them an unsuitable means of overthrowing the rule of capital. This line did not rely any more than that just mentioned upon the strength of the labor movement. It found a way out by overlooking to what extent the small bourgeoisie rests upon the same foundation of private property in means of production as capital, by believing that the proletarians would be able to accomplish the settlement of their accounts with the capitalists without being disturbed by the small bourgeoisie, the “people,” or even by their help. All that was needed was the republic and universal suffrage, in order to induce the government to introduce socialist measures.

This republican superstition, whose most prominent representative was Louis Blanc, found its counterpart in Germany in the monarchic superstition of a social kingdom, which was nursed by a few professors and other dreamers.

This monarchic state socialism was always but a hobby, sometimes also a demagogic phrase. It has never assumed any serious practical importance. On the other hand, the tendencies represented by Blanqui and Louis Blanc became practically significant. They acquired the power to rule Paris in the days of the February revolution of 1848.

In the person of Proudhon they met a powerful critic, He doubted the proletariat as well as the state and the revolution. He recognized very well that the proletariat would have to free itself, but he saw also that, if it fought for its emancipation, it would also have to take up the fight with the government for the control of the political power, for even the purely economic struggle depended upon this power, as the laborers felt at that time at every step, owing to the want of freedom to organize. Since Proudhon regarded the struggle for political power as hopeless, he advised the proletariat to refrain from all fighting in its efforts at emancipation and to try only the means of peaceful organization, such as banks of exchange, insurance funds, and similar institutions. For labor unions he had as little use as for politics.

In this way the labor movement and socialism and all attempts to bring both of them into closer relation formed a chaos of many tendencies during the decade, in which Marx and Engels formed their point of view and their method. Each one of these tendencies had discovered a piece of the truth, but none of them had comprehended it fully, and each one had to end sooner or later in failure.

What these tendencies could not accomplish, was perfected by the materialist conception of history, which thus assumed as great a significance for science as it did for the actual development of society. It facilitated the revolution of the one and of the other.

Like the socialists of their time, Marx and Engels also recognized that the labor movement appears inadequate when confronted with socialism in the question: What means is more apt to secure for the proletarian an assured livelihood and an abolition of all exploitation, the labor movement (labor unions, fighting for universal suffrage, etc.) or socialism? But they also recognized that this question was wrongly framed. Socialism, an assured livelihood of the proletariat and abolition of all exploitation are identical. The question is only: How does the proletariat come to socialism? And the theory of the class struggle answered: By the labor movement. True, this movement in itself is unable to secure a guaranteed existence and the abolition of all exploitation for the proletarian, but it is the indispensable means of not only safeguarding the individual proletarian against drowning in misery, but also of bestowing visibly more and more power to his whole class, intellectual, economic, political power, a power which increases continually, even though the exploitation of the proletariat increases at the same time. The labor movement should be judged, not by its significance for the limitation of exploitation, but by its significance for the increase of power in the proletariat. Not out of the conspiracy of Blanquí, nor out of the democratic state socialism of Louis Blanc, nor out of the peaceful organization of Proudhon, but only out of the class struggle, which has to last through decades, or even through generations, arises the power which finally can and must bring socialism to the front. To carry on the economic and political class struggle, to perform its detail work devotedly while filling it with the ideas of a far-seeing socialism, to combine harmoniously the organizations and activities of the proletariat into one, tremendous whole which assumes ever more irresistible dimensions, this is, according to Marx and Engels, the task of every one, whether a proletarian or not, who places himself upon a proletarian standpoint and wishes to free the proletariat.

The growth of the power of the proletariat, again, rests in the last resort upon the displacement of the precapitalist, little bourgeois, mode of production, by the capitalist mode, which increases the number of proletarians, concentrates them, increases their indispensableness for the whole society, but at the same time creates in the more and more concentrated capital the prerequisites for the social organization of production, which is no longer to be arbitrarily invented by the utopians, but to be developed out of the capitalist reality.

By this line of reasoning Marx and Engels have created the basis, upon which the social democracy rises, the foundation upon which the fighting proletariat of the entire globe places itself more and more, and from which it started out upon its victorious march.

This achievement was hardly possible, so long as socialism did not have its own science, independent of bourgeois science. The socialists before Marx and Engels were generally well acquainted with the science of political economy, but they adopted it uncritically in the form created by bourgeois thinkers, and differed from them, only in such a way that they drew other conclusions from them, which were friendly to the proletariat.

Marx was the first to undertake the analysis of the capitalist mode of production quite independently and to show, how much more deeply and clearly it may be grasped, if viewed from the proletarian instead of the bourgeois standpoint. For the proletarian point of view stands outside and above it. Only it, which regards Capitalism as a passing form, makes it possible to grasp fully its peculiar historical individuality.

This great achievement was accomplished by Marx in his “Capital” (1867), after he and Engels had proclaimed his new socialist position as early as 1848, in the Communist Manifesto.

By this means the proletarian struggle for emancipation had received a scientific foundation of a magnitude and strength, which no revolutionary class had possessed before him. It is true, however, that no other class ever faced so tremendous a task as the modern proletariat. It has to readjust the whole world which capitalism has disrupted. Fortunately it is no Hamlet, it does not greet this task with complaints. Out of the immense magnitude of this task it derives an immense confidence and strength.

Editor’s Note: This admirable brochure of Kautsky’s will be concluded next week with the final chapter, “The Combination of Theory and Practice.” No Socialist library will be complete without this work, the best study of Marx that we know. The Trustee Printing Co. expects to publish this translation in a 10 cent pamphlet. Orders should be sent in at once.

There have been a number of journals in our history named ‘The Socialist’. This Socialist was a printed and edited in Seattle, Washington (with sojourns in Caldwell, Idaho and Toledo, Ohio) by the radical medical doctor, former Baptist minister and socialist, Hermon Titus. The weekly paper began to support Eugene Debs 1900 Presidential run and continued until 1910. The paper became a fairly widely read organ of the national Socialist Party and while it was active, was a leading voice of the Party’s Left Wing. The paper was the source of many fights between the right and left of the Seattle Socialist Party. in 1909, the paper’s associates split with the SP to briefly form the Wage Workers Party in which future Communist Party leader William Z Foster was a central actor. That organization soon perished with many of its activists joining the vibrant Northwest IWW of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/thesocialist-seattle/080530-seattlesocialist-v08n377.pdf