The life and death of proletarian Pittsburgh artist John Kane; refused consideration in his life and exploited in his death by culture’s bourgeois gate-keepers.

‘A Perfectly Honorable Business’ by John Boling from Art Front. Vol. 1 No. 4. April, 1935.

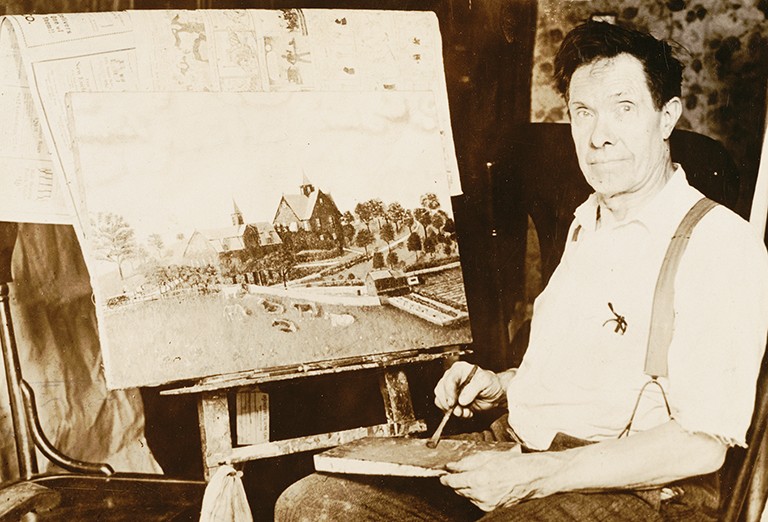

On a rainy day last summer a dozen men carried John Kane’s tubercular body to the grave. O’Connor and Balken from the Carnegie were in the procession, a New York art dealer had arrived for a day, the rest of the world hardly knew nor cared. The few weeks on his deathbed, while Kane fought against death to finish his last picture which he considered a masterpiece, had made exciting copy for the local papers. They could elaborate on a success story of the poor and simple ditch digger and house painter who had made good: from obscurity to gilded fame. They could not add, however, the old standby: from rags to riches. Kane died in poverty as he had lived his seventy-four years.

Little cognizance was taken in these reports of the tragic story of a man who sweated away a lifetime in coal mines and steel furnaces, who built the bridges and tunnels and paved the streets of Pittsburgh, and never was given an opportunity to paint the pictures for which Pittsburgh will be famous as time goes on. And surely no report will follow of what happened with the innocent canvasses when they became a matter of investment and speculation for greedy art dealers and shrewd collectors who profess to be “in business” and not interested in the creation of art. If Kane were alive today, he could have witnessed in his own case the decline and degradation of our “art lovers,” who for profit’s sake would reverse their vocabulary without the slightest scruple. He could have felt the hollowness and insincerity of those art “dealers”—they who stamped him an amateur, a dilettante and faker, while he was alive; who flared up into a glorifying ballyhoo making of him “the Pittsburgh Primitive” and “the American Rousseau” before the soil on his grave had barely hardened.

John Kane was a strong and husky man. He referred to himself as “frosty but kindly” like the winters of his youth in Scotland. He had a zest for living, although torn between the religious opposites of good and evil. Years of hard drinking followed periods of chastening abstinence; he alternated between bar-room fist fights and gentlemanly courtesy. All his life he wanted to attend an art school and learn how to express his nostalgia for pastoral scenes, the frustration of his own existence. This escape found a release later in the canvases of idyllic patches of nature amidst the hell hole of smoky Pittsburgh.

His Puritan background accounts for a conscientiousness and diligence, which was interfered with in his eternal fight against the devil who came to him in the temptation of liquor, the fitting opiate for paralyzing misery. His children left him, his wife left him. Old and crippled, jobless and starving, he was thrown out of his home. Several years later his landlord, Father Cox of Pittsburgh, advertised himself as patron of John Kane, American genius of the industrial scene. This happened after the glorious illusion of a Carnegie acceptance. Kane was swamped with press releases and photographs but his situation remained as desperate as ever. After ten years of separation his wife saw John’s picture in the papers. She returned to him who had been a “drinking bum,” was proud of him as he had made good, and hardly grasped what John had been doing nor what the world had acclaimed him for. John was still in no position to devote his time to picture painting—except in those rainy days when he was prevented from earning a livelihood brushing freight cars, barns and housefronts with weatherproof pigment.

Before it is too late, the legendary myths of Kane’s discovery and admission into the art field should be destroyed. A number of his pictures and “colored photographs” have been removed from circulation; it is doubtful whether we shall ever see his diaries full of homespun philosophic remarks and religious drawings reminiscent of Blake. Already a biography has been prepared, which not only omits dramatic facts of his life but attempts to cover up the tragic background of his idyllic pictures of escape with a patina of rose-colored saccharine. It already has become quite uncomfortable to remind the directors of the Carnegie Institute how old John used to peddle his bundle of canvases wrapped in newspapers to the museum. At the age of sixty-five he limped up the marble stairs to the offices of John O’Connor and Homer St. Gaudens to hear their repeated formula of hope. The doormen knew him already and hesitatingly let the shabbily dressed man pass the bureaucratic portals of that charitable institution of art.

Then in 1927, serving on the Carnegie jury, Andrew Dasburg in a rage of fury threatened to vote every picture down unless one of Kane’s loveliest canvases would be admitted. When the show was opened John’s “Scottish Highlands” became the hit of the exhibition. The child-like simplicity of this picture, the subtlety of colors, the primitive conception and execution fascinated the critics who had grown tired of the prevalent sophistication and accepted mannerisms. Dressed up in his Sunday suit, John stood nearby his picture surrounded with reporters and photographers. The museum directors benevolently patted his shoulder: “Well, John, how does it feel to be a famous artist?” Kane was embarrassed, did not know what to answer. “I always thought my pictures were good…” he said quietly. To this day, however, no museum or institution in the city which is glorified in his pictures has a canvas of Kane in its possession.

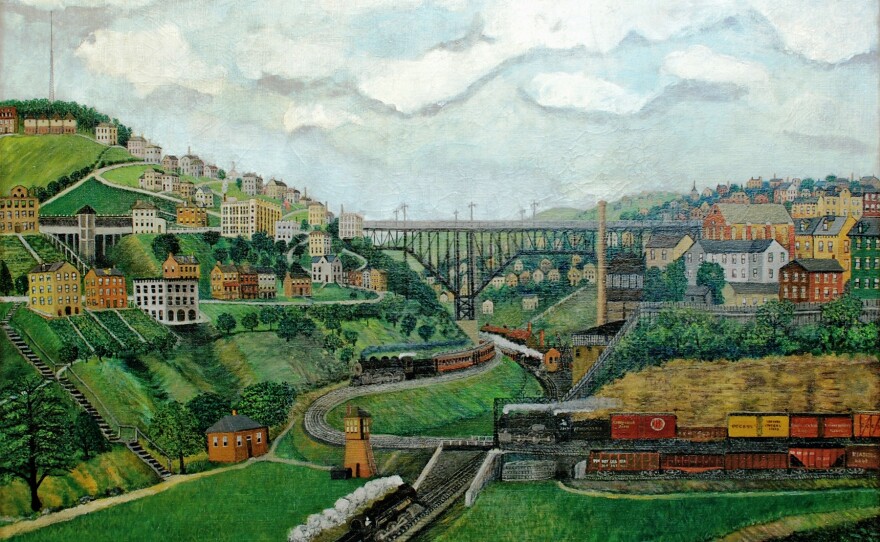

No trail-blazer of artistic expression in America, John Kane will probably remain the American Rousseau of an industrial era. A Catholic with Puritan background, he was a man who never knew life in the vibrating sensuous way the Frenchman lived and expressed it. Kane’s primitive approach, his naive composition, his astounding sensitivity in pigmentation, are as genuine as his lack of life and movement, his crudeness of figure anatomy, and the repetitious pattern of sheepish little clouds in a placid blue sky. Never did he paint the torturous hell of Pittsburgh and McKeesport as he had experienced it himself, never the sweat of work nor the industrialization of the country as he saw it. He viewed the city architecturally, certain buildings within the static frame of the settlement, typical little houses of the suburbs without stamina or character, two or three trains puffing against each other. A makeshift world into which the drawn-in pattern of every single cobblestone and blade of grass fitted perfectly. He had a great love for these streets and railroads which he had helped build himself. He worked slowly with painstaking attention to every detail and accumulated hundreds of sketches before he would begin work on a canvas.

We shall probably have the opportunity of seeing the few dozen pictures Kane left behind in several exhibitions. We shall see the Pittsburgh pictures and those escape canvases into the dream world of a sunny youth in Scotland which he never had. So little reality is attached to these pictures that the annual Scotchmen’s gathering in Pittsburgh’s Kennywood Park had to serve as model. He elaborated his wish-dreams in painting himself into the kilts and bagpipes, his adored brother Patrick, some of his relatives…But there is one picture we shall probably never see. It is of great importance in Kane’s life for he worked on it for many, many years and considered it his masterwork. It is a fair-sized canvas depicting Jesus in the Temple surrounded by the wise men of the land. Strongly reminiscent of the five and ten-cent holy pictures that soul-saving missions are keen to distribute, it represents one of the trashiest concoctions of every imaginable style and mannerism, completely out of line with Kane’s entire work. John loved these prints and had large quantities around him. They are the source of his inspiration, the secret of his originality.

Yet rarely has there been an opportunity offered to view within so short a period the complete prostitution of an artist and his work. His victorious crashing of the gates of the “Carnegie International” had brought no relief, but petty jealousy instead, from the local boys and academicians. They found occasion to expose Kane as a faker when he innocently sent a few colored photographs along with his canvases to an exhibition the Pittsburgh Junior League gave him. Everybody knew that Kane had been selling and coloring photographs for years. In fact, it was this preparatory brushwork on delicate little photographs that gave him courage enough to tackle a canvas. Yet the local papers swallowed the new sensation. Artists and collectors from all over the country voiced their faith in Kane’s sincerity and genuine qualities.

This unanimous credo, however, proved of little help with New York’s shrewd dealers of art. Always sensing a commercial possibility, Valentine Dudensing had arranged for a first one-man show of Kane’s work. As soon as he heard of the scandal at the Junior League, however, he dropped the show, furiously stating that he would not exhibit “such baloney” in his gallery. None of the other galleries would sponsor Kane’s debut.

In 1931 Manfred Schwartz returned from Europe and opened a gallery at 144 West 13th Street. He saw a picture of Kane’s at the Museum of Modern Art and at once negotiated with Kane. Schwartz deserves a great deal of credit for repeatedly showing Kane’s pictures and courageously fighting the many obstacles and handicaps which were put in his way. There is, however, an incredibly wide gap between showing and selling good work. Again Kane had good press notices but nobody would consider a Kane worth a hundred dollars. The fame and glory Kane had received through the Carnegie and through the exhibitions in New York could not help him to earn a living as a painter nor get him a much-needed job even as a laborer.

During the summer of 1931 Kane fell from a street car and injured several ribs. A few weeks later he slipped and broke another rib. He returned from the hospital a sick man. Schwartz came to Pittsburgh and found him in a dark and cold flat, desperate and starving. Impressed with the poverty of a painter he loved, Schwartz began to telephone the collectors and art lovers. They all answered that they were in no position to buy pictures. He called the Whitney Museum, told them about Kane’s condition and advised them to buy a Kane now if they ever intended to buy one. Schwartz finally told his father about the situation he had found Kane in and persuaded him to invest some money in Kane pictures. Schwartz returned to Pittsburgh and paid what he considered a “market price” for nineteen pictures of Kane. Three years later Kane was dead. Schwartz came to the funeral as he had come several times before to visit Kane.

Since last fall when Schwartz gave up his gallery no other gallery has made any effort to handle Kane’s pictures. Not even the Downtown and the Rehn galleries who specialize in handling American artists, considered Kane worthy of their patronage.

Macbeth and Valentine were the only bidders. Under conditions which are as straight and clean as most business dealings are today, Schwartz sold nineteen pictures to Valentine at a profit. Valentine at once began to establish a monopoly in buying up every Kane in the market.

While Kane was alive he could hardly get $50 for a picture. Today with sufficient ballyhoo as the “original sponsor of Kane,” Valentine went into speculation at the rate of $7,500 per picture. He contradicts himself when he tells some people that he has sold two, and others that he has sold four pictures to Albert C. Barnes. There are also many conflicting rumors as to the stupendous prices Barnes is supposed to have paid for the Kanes. The truth is that Valentine, in order to whip up the publicity attracting big collectors, practically gave the pictures away to Barnes. Now that Kane is dead the Whitney Museum has bought one of his canvases. They paid less than $1,000 to Mr. Landgren who in turn paid less than $100, an amount larger than the Whitney Museum would have had to pay to keep Kane happy and alive.

All these deals and profits, the starvation of the artist to the benefit of the dealers and collectors, of course, are perfectly legal, perfectly honorable. It is, no doubt, less honorable to state that Kane would have lived his last few years far more happily, and that he would have been able to paint many more of these pictures with as little money as his “original sponsor” demands now for one picture. It is time that we become fully aware that our society permits and honors those men who not only let the artist starve but indirectly wait for his death in order to boost so-called prices and market values, “plowing under” and destroying the surplus of his work following the set example of our government. The only difference may be that our government at least partly pays for the destruction. So there is really no case against Mr. Dudensing, who belongs to the honorable art dealers of our city.

John Boling.