Not as well known as the later fights around Matewan and Blair Mountain, the 1912-13 struggle of West Virginia’s Kanawha Valley miners was just as brutal and desperate a confrontation, with dozens killed and whole communities forced into the mountains. Many of the instances of mass violence against the labor movement have seen immigrant workers as the prime targets. West Virginia was an exception, with largely native-born white and Black miners facing the full might of the coal operators, their gun thugs, and their state. The Socialist Party of West Virginia had around 1200 dues-paying member in over 30 locals at its height in the midst of the Kawanha Valley War. Here the Party’s State Secretary and a Socialist lawyer defending the miners give the first part of an essential primary record of that conflict.

‘A Resume Of The West Virginia Struggle, Part One’ by Paul J. Paulsen and Harold W. Houston from The Wheeling Majority. Vol. 7 No. 23. August 21, 1913.

The Recent Clash Between the Coal Operators and the Miners of Paint and Cabin Creeks Was Heard Around the World.

THE STORY OF THIS STRUGGLE IS VIBRANT WITH HUMAN INTEREST

And Contains Many a Lesson For the Hosts Of Labor As They March On To Ultimate Economic Emancipation. A Graphic Pen Picture Of the West Virginia Coal Miner On His Native Heath. United, the Working Class Is Invincible; Divided Its Doom Is Certain

The West Virginia miners have furnished one of the most memorable struggles in the history of battles between Capital and Labor. The clash between the coal operators and the miners of Paint and Cabin Creeks was heard ’round the world. Lined up with the operators was the power of the State government, the press and the vast army of minions who always fatten on the wealth wrung from the workers. Against this apparently invincible army, backed by the militia and the courts, the miners fought a winning battle. They emerge with many a trophy and the flag of liberty–the flag of unionism–for the first time in many a long year flies from the tipple of Cabin Creek–America’s Little Russia. The story of this struggle is vibrant with human interest, and contains many a lesson for the hosts of Labor as they march on to ultimate economic emancipation. For this reason we give below a short resume of the most salient features of this heroic effort to win West Virginia for unionism.

Paint and Cabin Creeks are two mountain streams running south from the Kanawha River in the eastern part of Kanawha county, and are separated only by a ridge of lofty timbered hills. On these two creeks are located a great number of mines employing between six and seven thousand miners. A majority of these miners are native Americans, many of them having been reared here in the mountains, and they possess an innate love of liberty that illbrooks the slavery attempted to be forced upon them by the coal barons of this state.

Previous to April 1, 1912 Paint Creek was partly organized. In view of the fact that the contract under which the miners and operators were then working would expire on April 1, 1912, a joint conference was held in the city of Charleston during the month of March of that year for the purpose, if possible, of negotiating a new contract. In this conference the miners demanded an increase. They demanded an increase of five and one-quarter per cent., that being what is known as the Cleveland demand, this increase being accorded to all the miners throughout all the organized sections of the country. The Kanawha operators the operators along the Kanawha River proper refused the increase called for by the Cleveland demand, but finally agreed to pay one-half of the Cleveland scale. The Paint Creek Collieries Company, the principal operator on Paint Creek, after numerous conferences, flatly refused to grant any increase whatever. The increase demanded by the miners of Paint Creek would have approximated one and one-half cent per ton. The refusal of this small increase is what, in reality, precipitated the now famous strike of the West Virginia miners.

The Paint Creek Collieries Company operates eleven or twelve mines on Paint Creek and employes about 2500 miners. But a very small per cent of these were members of the United Mine Workers at the time this controversy arose. During the latter half of April the strike call was issued, and the miners, both union and non-union, promptly responded to the call. The mines were all closed even those operating on the head of the creek, and who were not involved in the original controversy, and immediately the operators commenced the importation of their army of private guards. These guards, many of whom were ex-convicts and thugs, were furnished principally by a detective agency, known as the Baldwin-Felts Agency, with headquarters at Roanoke, W. Va. and a branch office at Bluefield, W. Va. These were furnished the operators in any number desired and were paid approximately $75 per month. Since these “guards” must play such an important role in subsequent events it becomes important to explain the purposes of their employment.

With the failure of the operators to concede the small increase demanded by the miners, the war on the union of the miners commenced. The operators knew they must crush every attempt of the miners to form a union. To do this they distributed these armed guards all along the creek with orders to drive every agitator from the field. In addition they erected small fort, one of which armored with railroad iron and boiler plate, still frowns from the mountain side at Mucklow. There was scarcely a day but chronicled some heinous assault made upon the miners or some member of their families by these brutal gunmen. Day after day the strike went doggedly on, but on the part of the miners there was little of that militant spirit that stamps a successful struggle.

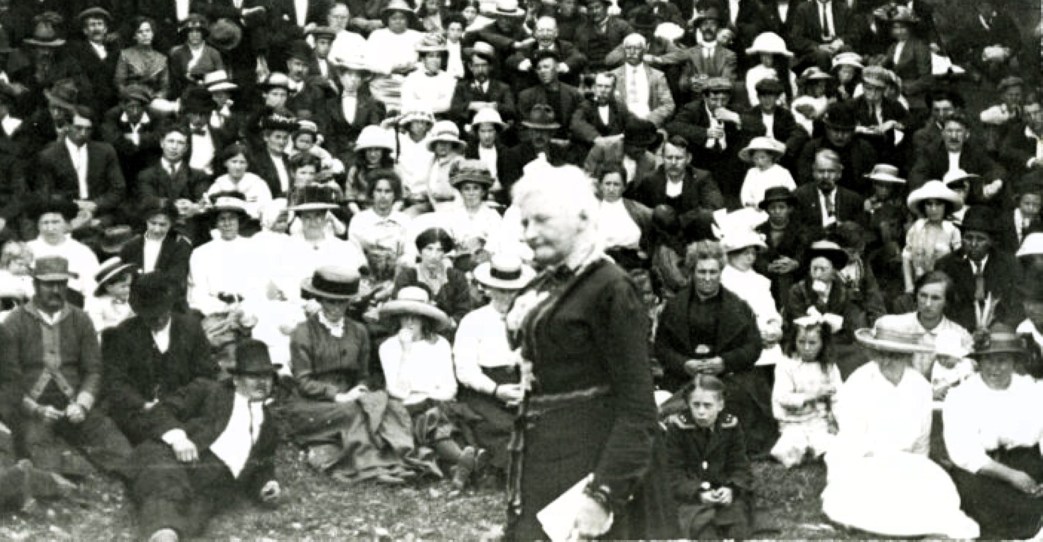

But in June something happened. That something was the silent advent of “Mother” Jones. From that day new life was infused into the miners. The spirit of the battle now rose over the mountains and filtered down on unorganized slaves of Cabin Creek. For the long years they had been without the semblance of organization, and were therefore at the mercy of the conscienceless operators of that section. They knew that the fight of the Paint Creek miners was their fight alone. But no organizer could ever penetrate Cabin Creek without taking his life in his hands. The creek was infested by murderous guards. Many a harrowing tale can be told of the murderous work of these human ghouls. Their cry was heard by Mother Jones and she determined to go to their relief.

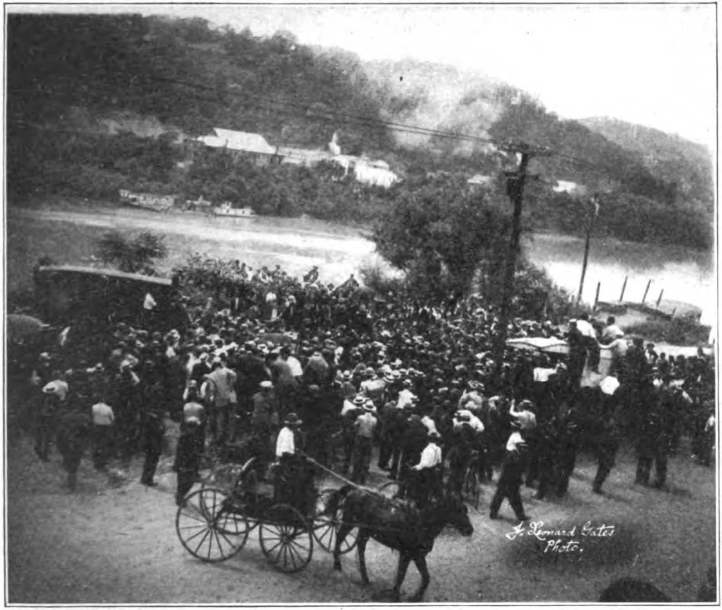

One evening in late July when darkness was settling down on these mountains, two me could be seen boarding a train at Charleston with small packages under their arms. They went to Cabin Creek Junction, and, after narrowly escaping death at the hands of company guards, got their packages safely aboard the Cabin Creek train. The silent winds of the night carried to the doors of the miners little hand-bills calling for a monster mass meeting at Eskdale, to be addressed by Mother Jones. The impossible had happened. Mother Jones the terror of the slave drivers, had scaled the impregnable wall of “Little Russia.” The call of Unionism reverberated throughout the valley. The miners and their families, men, women and little children, trooped in a vast army to hear the inspiring words of their old leader. From that hour on the operators had a fight on their hands and subsequent history has taught them that is was both a losing and a costly one. From end to end of Cabin Creek there was a complete tie-up of all the mines, reaching even to Coal River in an adjoining county. What was transpiring on Paint Creek was now duplicated on Cabin Creek. Here, too, came trooping the private army of hired thugs and gunmen. Here too, were duplicated the brutality and lawlessness that was flaming to the world a hideous picture of the coal barons as the most lawless and anarchial of all criminals.

Now came the strike-breakers, a motley crew of the off-scourings of the great cities. They were piloted into the district by the guards, after having been virtually kidnapped by the most shameless lies and representations of the emissaries of the operators. Many of them had never seen a coal mine and didn’t know a coal pick from a tooth-pick. Their attempt to mine coal was ludicrous had it not been for the tragedy back of their lives. Like the miners, they, too, were the victims of the industrial masters of the State.

Failing to break the ranks and spirit of the miners by use of strike-breakers and armed thugs, the operators felt that something had to be done. Finally they hit upon the scheme of using the state government. Employers are not slow in recognizing the services of government. What are governments for these days but to help employers wring wealth from the workers? That is their history. And the operators know their business. They went to the state house at Charleston and invoked the majesty of executive power. They called for the militia-kiki kids, and the kids came. The strike section was flooded with militiamen, with inflated upstarts, dangling sabres, at their head. From the very beginning of the strike the miners had made all honorable effort to effect a settlement. At first they proposed a board of arbitration, to be composed of two miners and two representatives of the operators, they to choose a fifth man. But from the very first the operators refused to even meet the miners representatives, saying that they had absolutely nothing to arbitrate. Finally, after numberless efforts to obtain a conference with the operators and after severel attempts of Governor Glasscook to get the operators to arbitrate, the governor appointed an investigating committee of his own choosing. The committee took considerable evidence and made personal visits to the strike zone, and made a report to the governor.

Though the committee, having no representative of the working class in its make-up, and therefore biased in behalf of the operators, made a report deeply implicating the stubborn operators in the charge of oppression and extortion, the operators still refused to arbitrate or meet the miners. The miners had no rights that the operators were bound to respect.

This industrial drama was partially staged in the city of Charleston, 20 miles away. There is the headquarters of the coal oligarchy of West Virginia. It is there that the operators live in the most palatial homes, built out of the blood and tears of countless miners Mother Jones came to Charleston to address a monster mass meeting of miners and other workers. That meeting made history. It was held in front of the court house, and though there is a great open space in front the meeting filled every available space. The meeting overflowed out in the streets. Windows and house-tops were loaded with men women and children straining to catch the words of Mother Jones. She told of the wrongs being heaped on the miners, the men who were producing the wealth that made the material prosperity of the State and Nation. These people had never heard that story before, and it thrilled them with the conviction that the cause of the miners was a holy one.

A number of other meetings were held in Charleston, all with the object of acquainting the people with the miners’ side of the controversy. The operators then dominated the daily press. These papers exploited the operators’ side by the most notorious lies. Every incident of the struggle was tortured into something prejudicial to the miners. Every assault made on the miners by the guards was converted into an assault by the miners. This harlot press spread their false representations broadcast. The representative of the press associations was a government lick-spittle, occupying an office in the military headquarters free of charge. In his absence a militia officer took his place.

The San Francisco Bulletin sent a woman across the continent to find out why the truth could not reach the public. Mrs. Older, the reporter for the Bulletin, told why in Collier’s Magazine.

The only paper at that time voicing the cause of the miners was The Labor Argus, a weekly paper published at Charleston. From the first it had been hurling broadsides at the operators and their hired guards. Its circulation was limited, but it did great work for the miners.

So these meetings were held to reach the public. It must know the truth. An infamous cause cannot long withstand adverse public opinion. To know the true character of the operators was to condemn them. Mother Jones brought the children of the miners to Charleston and marched them along the crowded streets. They were fine-looking children, but they too bore the marks of the struggle. They were living indictments of the coal barons. Their clothes were tattered because their fathers had been robbed by the operators. Their cheeks were pale and hollow because bread had been taken from their mouths by the heartless oligarchy of Greed that was devouring their young lives. This little army of God’s innocents told the story of the miners’ wrongs and sufferings in thunder tones.

Then came the meeting of Mother Jones on the capitol steps. With a delegation of miners and their families she invaded the State House grounds and spoke from the steps. It was a monster demonstration. The officials and the capitol attaches came out to hear her. Governor Glasscock mustered up enough courage to leave the seclusion of his office to listen to the speaker. But a few words was enough for him. Mother Jones, in her characteristic manner, pilloried the Governor for the infamous part he was taking in the effort to drive the miners back to the mines. This meeting, too, made history.

By this time the State was beginning to be aroused. From all parts of the State came a demand for a settlement of the strike. Business, religious and civic bodies were calling on the Governor to stop the industrial war that was piling a load on the tax-payers. So the Governor called a meeting of representative organizations to meet at Charleston to discuss some method of settlement. The meeting was held. Immediately upon its convening the operators started to make a “rough house.” They wanted to exclude all representatives of the miners. So the meeting, after a stormy session of a couple of hours, broke up in a row.

Then the citizens of the state took the initiative and called a meeting themselves. It was held in the House of Delegates of the capitol. It was a monster meeting of citizens from all parts of the state. Among the speakers were President John P. White and Vice-president Frank J. Hayes of the United Mine Workers of America. They spoke for the great organization of miners. They told of its aims and objects, and of the sunshine that it had brought to the humble homes of the toilers. It was an inspiring story. It drove home to the hearts of the miners the lesson that liberty can come only through unionism. Singly they are helpless. United they are invincible. Shoulder to shoulder they can win a world.

In early October martial law was declared off and most of the militiamen were withdrawn. A number of them, however, with the consent of the governor enlisted in the services of the mining companies as “mine guards,” thus openly giving to the company the same service that had been performed covertly under cover of their kiki uniforms. As the wages of these mine guards were paid by the operators and the operators directed them in the work they were to perform. The governor claimed that he would do away with the “Baldwin thugs” formerly employed by the operators, but they remained nevertheless and carried on their nefarious work in conjunction with the former members of the state militia. The work of exterminating agitators and beating up organizers and representatives of the United Mine Workers of America went merrily on.

However, the spirit displayed by the miners in this memorable contest could not be dampened and with every new outrage inflicted upon them there came renewed courage to win at all cost.

About this time, or, to speak more accurately, about November 1, the mines at Dorothy employing about 800 men, signed an agreement with their employes on a basis that was satisfactory, and operations were immediately resumed. Three weeks later the mines at Eskdale on Cabin Creek made a similar settlement and shortly thereafter the mines at Crown Hill, Crelyan, Coalburg, the Lewis mines at Cabin Creek Junction and other smaller operations made like settlements and the men went to work. But all this while the Paint Creek Collieries Company and the Cabin Creek Consolidated Coal Company, the largest companies in this section, with almost limitless resources back of them, fought on with a brutal determination to destroy the last vestige of unionism in that section. They are dominated by men who are absolutely unscrupulous and who believe that a worker has no rights that they are bound to respect.

During the early part of the strike the miners made every possible effort to secure the protection that the law guaranteed them. They appointed a number of delegations at different times to call upon the governor for the purpose of laying their grievances before him. They told the governor how their homes were being invaded, their families assaulted and insulted, and how life was made almost unbearable by the company thugs. Governor Glasscock, a political child of the Davis-Elkins oligarchy, listened to the story of these outrages, but each time sent the petitioners away without hope of relief. Failing here, they appealed to the prosecuting attorney and sheriff of Kanawha county, whose duty is was under the law to protect citizens from molestation at the hands of these lawless thugs, but they too were political hirelings of the operators and they refused to do anything. At last, almost despairing of gaining legal protection, they appealed to the circuit court of Kanawha County, presided over by the notorious Sam Burdette, for an injunction against, the companies maintaining their private army of thugs and marauders. The miners learned here what they always learn, that the courts are on the side of wealth. They learned that laws are made for the benefit of those who have money. They had often heard of injunctions being granted against workingmen, so they thought they would try an injunction against the coal barons. But the court summarily kicked the mount of the “temple of justice” without granting their prayer for an injunction. Seeing that they were denied legal protection for their families and their homes, they had but one resort left. They must protect themselves. They had to rely upon the law of self-protection. Therefore many of them armed themselves with rifles and determined to put an end to the barbarous treatment of themselves and their families.

The clashes that followed between the thugs and miners occasioned a second declaration of “martial law”. This happened about November 15th. Just here began one of the greatest crimes ever inflicted on a free people. The operators, using the government, had the governor create what has become known as a “military commission.” It was composed of five members of the militia, and a judge-advocate as prosecutor. The governor declared that this “court” was to take the place of the civil courts of the county, though the latter were peacefully trying cases but 20 miles away at the capitol of the state and the seat of the county. The governor went further–he declared all civil law abrogated and made an entirely new code of law in its place. He declared that any person might be sent to the penitentiary for the smallest offense. This infamous military commission, composed of ignorant political under-strappers, set to work railroading miners to the penitentiary. It soon had about 16 men in the penitentiary serving terms varying from two to ten years.

The people were slow to awaken to this unheard of proceeding. The attorneys for the miners, H.W. Houston and A.M. Belcher, at once appealed to the Supreme Court of Appeals or West Virginia for a writ of habeas corpus to inquire into the legality of these sentences. The writ was promptly granted, as the law provided it should be and the prisoners arraigned. Lengthy arguments were made in the bitter legal fight that followed, and the court, to the utter amazement of all constitutional lawyers, upheld the military commission and confirmed the infamous sentences. Preparations were immediately made to take the cases to the Supreme Court of the United States at Washington, and just when the cases were ready for presentation the governor pardoned the prisoners, thus leaving the attorneys for the miners without a case. In the meantime this outrage upon the people of the state and nation reached the public, and the Congress of the United States began to take notice of it.

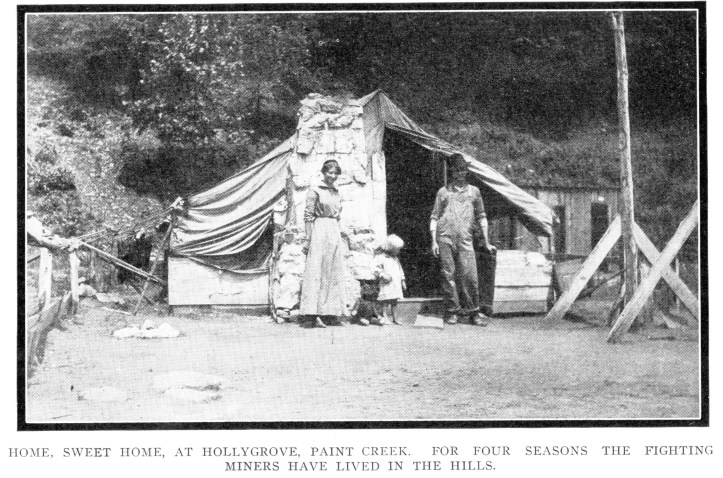

The coal barons, with the state government, the militia and the courts back of them and still failing to break the Indomitable spirit of the men who were fighting for their home and fireside, now awaited “infantry of the snow and the cavalry of the wild blast.” The winds of winter bite keenly in the mountains and the operators thought it would chill the blood of these mountaineers. But they knew not the blood that flows in the veins of these sturdy working class warriors. The thugs and gunmen now commenced driving the miners from their shacks. Not by process of law–that is too slow for industrial bandits–but by armed detectives without law. They went to the “homes” of the miners in large bodies, heavily armed, and pitched the household goods into the roads. They would interrupt the families even at meal times, and in many cases wantonly assaulted the miners’ families. In one case, that of Mrs. Sevilla, the thugs struck her in the abdomen with the butt end of a rifle when she was in a delicate condition, causing the death of her unborn child. Evictions were made by wholesale. Little villages of tents sprung up along the railroad–the tents being furnished by the miners’ organization.

With the passing of summer and the falling of the leaves of autumn came the approaching days of winter. Christmas was not far away. These miners, innately a deeply religious people, never forgot the birthday of the Carpenter. The children must have clothing and shoes to protect their little bodies from the biting cold of winter. Mother Jones never forgets the little ones. While others had left for home to spend the holidays with their families, Mother Jones stayed on the scene of battle. On Christmas eve she held a monster meeting at Eskdale. On Christmas day she held another great meeting at Holly Grove, and the miners’ families, even the little children, came to hear her inspiring words. They put new hope in the hearts of the miners. The relief orders of the union are known throughout the district at “Mother Jones Bread Checks.” An extra allowance was made the miners for their Christmas.

Failing to break the strike by the use of the state government, the militia, the courts, the army of thugs, and the suffering of winter, the operators were growing desperate. Such fighting determination was something new to them. They had become used to unprotesting submission on the part of the slaves of the mines. They now summoned to their assistance the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway Company. The company gladly responded, giving an illustration of the solidarity of capital. The railroad company took a baggage car to their shops at Huntington and lined it with iron and steel plate with port holes from which to fire rifles and machine guns. On one dark night in February, 1913 they manned this car with railroad police and company thugs, armed to the teeth. On board was the notorious Quinn Morton, a bitter enemy of unionism, the sheriff of the county, and his deputies. When this armored train pulled out of Cabin Creek Junction and went on its journey of murder, the men put out all the lights. About two miles away was the tented village of Holley Grove, filled with the miners’ families peacefully sleeping, unconscious of the oncoming danger. Just as the train reached the outskirts of the village, a signal was given by the engineer and a veritable hell of fire was rained into the homes of the miners. In the roar could be heard the thunderous rattle of the machine guns doing their murderous work. After the train had passed, Quinn Morton, superintendent of two large coal companies, said, “Boys, let’s go back and give them another round.” The night attack made the women and children terror-stricken. When day dawned they found their homes pierced through and through with bullets. Susco Estep, a young miner with a wife and several small children, was cold in death, murdered by a bullet from one of the machine guns. Mrs. Hall, a miner’s wife, had both feet shot to pieces, making her a cripple for life. It was a miracle that a score or more were not killed. Only providence could have saved them.

The massacre of Holly Grove shocked the nation. The story of this unspeakable crime is to be found in the records of the Senatorial Investigation Committee. Following this massacre came the report that another attack was to be made by the armored train. The miners, to meet it, got out their guns. Three days later, when the miners were looking for the attack a clash came between the armed guards and the miners at Mucklow, in which a number were killed on both sides. Then again came “Martial law,” with its tin-horn soldiers to do the work of breaking the strike. Came too, the “military commission,” and once again commenced the farce of railroading the miners to the penitentiary. Wholesale arrests followed. At one time more than 200 miners filled the military “bullpens”. Then the governor introduced the barbarous. “lettres de cachet,” formerly used in the days of despotism in France, by which he sent his uniformed emissaries to other parts of the State outside of the martial law zone and seized “agitators” and other “undesirable citizens.” Among those thus abducted were Mother Jones, the editor of the Labor Argus, Paul J. Paulsen, Charles Batley and many others, all Socialists. Attorneys for the miners again appealed to the Supreme Court for writs of habeas corpus. They were again granted, but on the hearing the court refused to discharge the prisoners, holding the astounding doctrine that the will of the governor was the only law, and that he could snatch citizens from their homes in any part of the state and try them by his infamous military court. An appeal was then made by the miners’ council to the Circuit Court of Kanawha county for a writ of prohibition to prevent the military court proceeding with the trials. The writ was issued, but upon the hearing it too, was dismissed, and the prisoners remanded to the military commission for trial. The trial went on and sentences were imposed upon the prisoners, in many cases approximating 15 years.

In the meantime, and during the trials of Mother Jones and about fifty others, Governor Hatfield succeeded Governor Glasscock. The trials were halted to permit the militia officers and members of the governor’s staff to attend the inaugural ceremonies. After that the trials proceeded and sentences imposed. By this time the “military commission,” an institution forbidden by English law as early as Magna Charta, in the year 1213, was becoming known throughout the entire nation. A mighty protest began to be heard, even in the halls of Congress, and an investigation was called for by the country. Although the military court imposed the sentences, the new Governor refused to approve them. He sent the prisoners to various jails over the state and held them until about the 22d of May, when they were released.

The Wheeling Majority of West Virginia began in 1907 as a project of several of the region’s unions and labor federations including the Ohio Valley Trades and Labor Association, the Belmont County Trades and Labor Association, the Tin Plate Workers International Protective Association of America, and the West Virginia State Federation of Labor. Socialist Party member Walter B. Hilton edited and managed the paper eventually bringing the weekly firmly into the Party’s orbit. One of three well-established local Socialist papers in West Virginia during the 1910s, the Majority’s motto, “For Those Who Plod With Plow or Pick or Pen.” Allied with the Party’s electoralist center, the paper like so many was a victim of the Red Scare after World War One and folded on April 29, 1920.

PDF of full issue: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86092530/1913-09-04/ed-1/seq-8/