A critical, industrial unionist, look at Philadelphia epic, if incomplete, General Strike of 1910.

‘Philadelphia in Revolt’ from Solidarity. Vol. 1 No. 15. March 26, 1910.

“General Strike” in “Sympathy” With Car Workers, With Power House Men at Work.

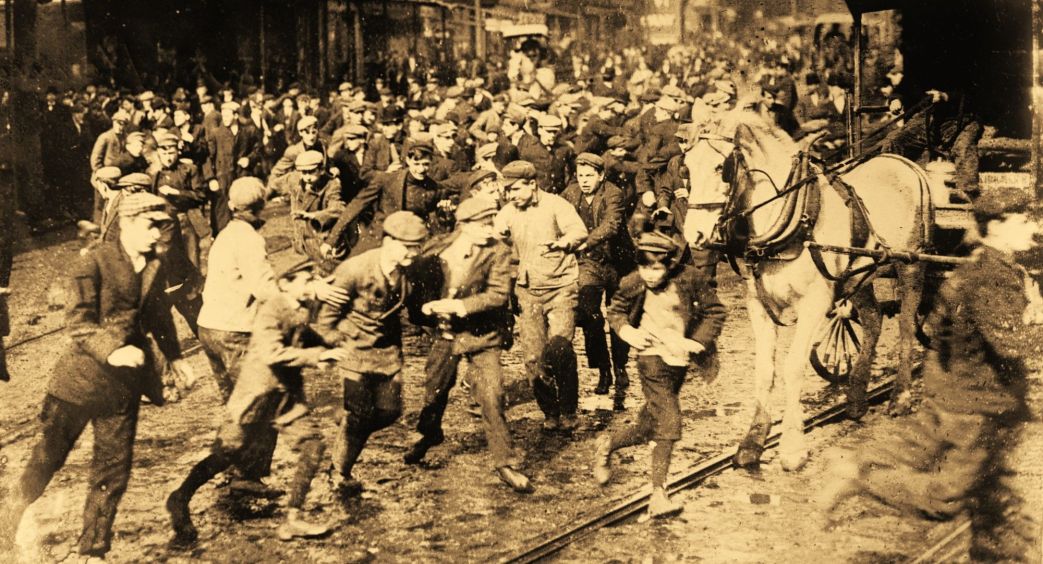

Comment on the situation in Philadelphia could practically be left unchanged from week to week, so unchanged is the situation so far as its essential features are concerned. Details, of course, vary as the strike progresses. Different individuals–labor leaders and others–are brought before the public in the press. Different people are killed whether with the bullets of the Cossacks or by the incompetence of strike breakers in handling cars. Different mobs assemble in different parts of the city and stone different cars. Different groups of orderly, well-behaved workers assemble in different parts and have their heads cracked in different places by different troops of Cossacks. But the essential features of the situation remain practically the same.

It presents itself as a medley of contradictions from which, greatest paradox of all, truths of the highest value to the working class may be learned. This is what we see: The car men–SOME OF THEM–out on strike. All told about 1,400 (this included also the members of a rival organization, the Keystone Carmen) remained steadfast to the company. Many of the firemen in the power houses wanted to come out at the same time, and no doubt at that particular moment all the power house men could have been brought out without much difficulty. But the national organizer of the Carmen, C.O. Pratt, discouraged it. After a while murmurs in favor of a general strike in sympathy with the car men began to be heard not only among unionists, but among the unorganized workers as well. Their leaders discouraged it. Trade agreements would be ruptured and craft autonomy in danger of being swamped in the rising tide of class solidarity. Still the insistence grew among the rank and file and finally the leaders were forced to take notice and the general strike was called. But the power men who ought to have been called out first of all were left at work. Chief McLaughlin, of the Philadelphia police, had threatened to fill their places with municipal employes in case they should be called out and either the bluff worked or the firemen’s ardor had by this time cooled off. They stayed. Most of them are at work now.

Very significant was this fact on the part of the municipal authorities. The capitalist class realize very distinctly the sources of the workers’ power and the strategic points on the field of industrial battle.

Well, the general strike was called and about 150,000 men of various unions and of no union responded. They are still out. But the power house men stayed in.

Not all the craft unions came out when they were called, either. The Brewery Workers, for example, which it is claimed is nearer being on an industrial footing than any other organization connected with the A.F. of L. This will come as something of a shock to those who have long been contending that the A.F. of L. was itself evolving into a revolutionary industrial organization and have pointed to the Brewery Workers as a bright and shining example. Or perhaps the Brewery Workers simply realized the futility of their going out on strike, while the men in the power houses remained on the job.

At all events the A.F: of L. soon discovered the futility of a general strike of this kind in one city. There appeared to be a good deal of futility lying around somewhere wherever it came from. So at the meeting of the State Federation in Mach in New Castle a resolution was adopted to submit the question of a general strike all over the state to the different local unions of the various crafts and they are now as we write (March 18th) allotting on it. They are now balloting on the proposition of a state wide general strike and at the same time the representatives of the striking car men and their employes are meeting in conference to discuss ways and means of ending the strike. The demands that the men are insisting on are pitiful in the extreme in view of the fact that they are supposed to be backed by the threat of a general strike. They are nothing more than this: That the car men who are now out be all re-instated in their former positions. The company is willing enough to grant that request if it can only see its way clear to take care of the scabs to whom it has, meanwhile given employment or promoted to better runs.

The whole situation seems rather ridiculous to one who has some conception of what a general strike would actually mean if conducted along industrial union lines by a well systematized industrial organization acting and interacting with system and harmony in its various components parts. And yet.

The fact remains that the capitalist class, including the City and State authorities, are even afraid of this very imperfect, incomplete and poorly organized general strike. So much so that they have been sending representatives to act as go betweens and messenger boys between the strikers and the company to patch up some sort of a truce some way. City Director Earle has been to see the strikers. So has the State Treasurer John O. Sheatz and it is reliably reported that he was sent from Harrisburg on this special mission by Governor Stuart. The Philadelphia Board of Trade has resolved “that the general strike is not revolutionary.”

They are not far out of the way. The capitalist class don’t like very well the idea of a general strike, no matter how crudely and clumsily conducted. Even the name of the thing has a bad sound in their ears. A general strike even when it is lost is a great source of terror to the capitalist class because of its effect on the working class mind and their relations toward each other. Trade agreements are ruptured and by so much the labor fakir is unhorsed. The workers get the idea of standing by each other and that “an injury, to one is an injury to all.” That’s bid for capitalism. No, the bosses don’t like the idea of general strikes.

We spoke of the results of a general strike even if it were lost. But in strict truth and the exact use of language a general strike never could be lost. So-called general strikes like the one in Philadelphia–which are nothing more than a somewhat extended application of the principles of the sympathetic strike, might be in a measure. Though even then the net gains for labor in the end are almost sure to overbalance any temporary losses. This the capitalists know and fear. Witness the wail that is going up to high heaven just now in the capitalist press, all over Pennsylvania, against the possibility of the Philadelphia situation being made state wide. But a general strike that was such in reality and in truth as well as in name; a strike conducted by ONE BIG UNION built on class and not on craft lines; a union broad enough in its scope to take in the whole wage earning class in its several Departments why such a strike as that would simply be the taking possession of industry by the workers themselves.

We are coming to that, and rapidly.

The most widely read of I.W.W. newspapers, Solidarity was published by the Industrial Workers of the World from 1909 until 1917. First produced in New Castle, Pennsylvania, and born during the McKees Rocks strike, Solidarity later moved to Cleveland, Ohio until 1917 then spent its last months in Chicago. With a circulation of around 12,000 and a readership many times that, Solidarity was instrumental in defining the Wobbly world-view at the height of their influence in the working class. It was edited over its life by A.M. Stirton, H.A. Goff, Ben H. Williams, Ralph Chaplin who also provided much of the paper’s color, and others. Like nearly all the left press it fell victim to federal repression in 1917.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/solidarity-iww/1909-1910/v01n15-mar-26-1910-Solidarity.pdf