Eugene Debs writes on the 30th anniversary of 1888’s nearly year-long, bitter lost strike against the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad, remembers his activities, points to the failures of its craft union leadership, and wonders what might have been if the strike had won.

‘The Strike That Should Have Won’ by Eugene V. Debs from the New York Call. Vol. 11 No. 90. April 14, 1918.

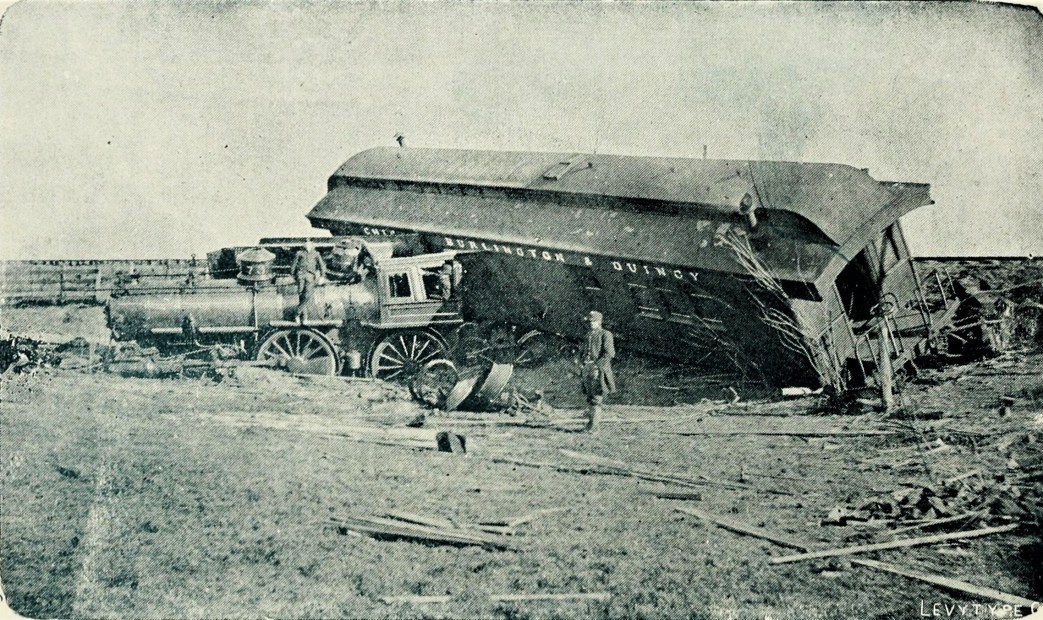

Many an old locomotive fireman and switchman has cause to remember the strike on the Burlington system, one of the fiercest industrial battles ever fought in this country.

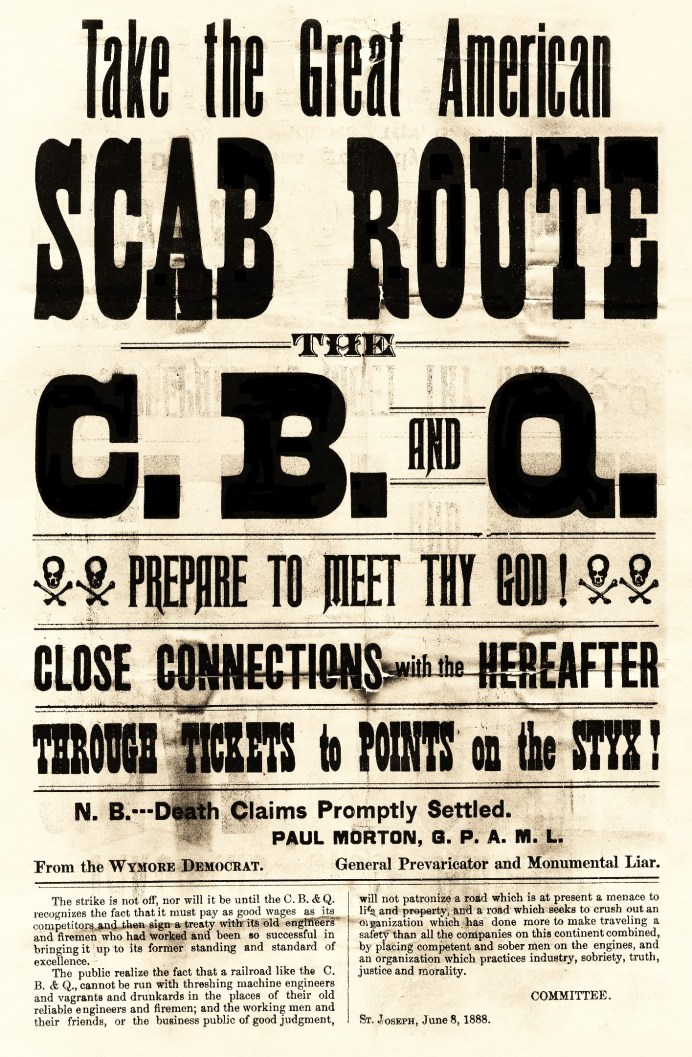

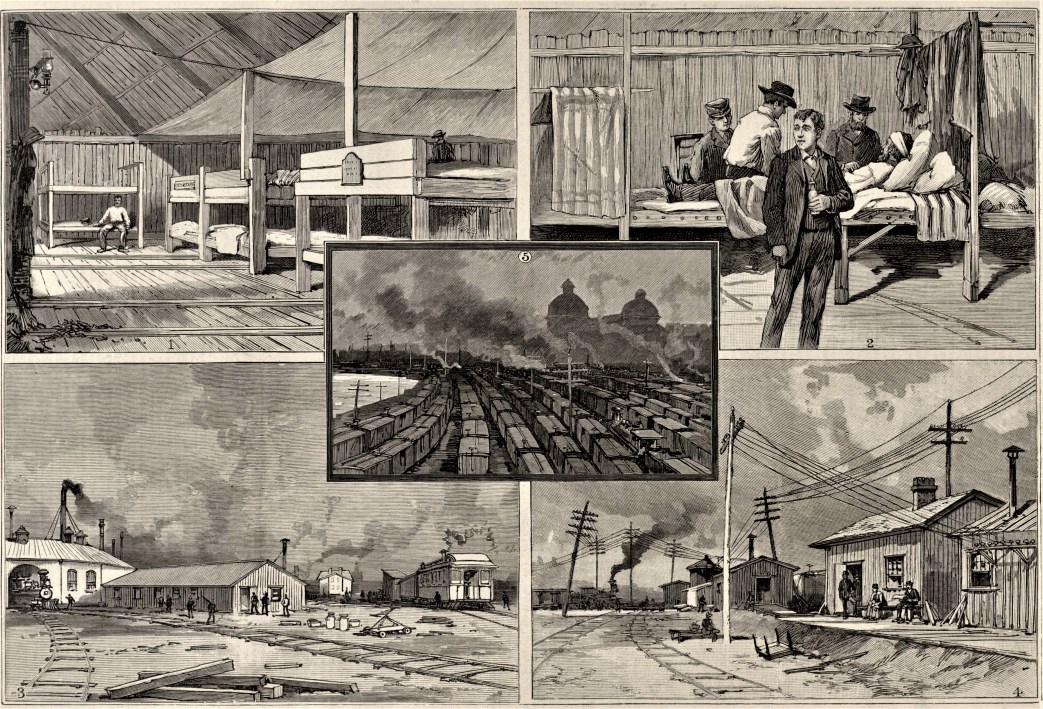

The strike was declared on February 27, 1888, by the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers, with P.M. Arthur as Grand Chief, and the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, with F.P. Sargent as Grand Master. A few days later the Switchmen’s Mutual Aid Association also struck. The engineers and firemen came out to a man, and so did the switchmen. The system was paralyzed and almost at a standstill.

The strike was led by Grand Master Sargent who, under the laws of their respective brotherhoods, had complete control and unlimited power to act.

The conductors on the system scabbed outright, openly siding with the company, piloting the scabs over the system, and declaring their intention to defeat the engineers. The reason given for their hostility was that their order was bitterly opposed to strikes and that, besides, the engineers under Arthur had never cared for others but had always pursued the selfish policy of looking out exclusively for themselves, a fact which could not be denied at that time. The brakemen, switchmen, and others felt much as the conductors did toward Arthur and the engineers, but refused to take sides against them.

Shortly after the strike was declared, Wilkinson and Monahan, chief executive officers of the brakemen and switchmen, respectively, called at the Chicago headquarters to tender to Arthur and Sargent the sympathy and support of their unions. My surprise and chagrin may be imagined when Arthur arose and said solidly: “This is a fight between the brotherhoods and the ‘Q’ and all we ask is that you keep hands off.”

The two officials were highly indignant, as might be expected. I may not put in print what they said to me in comment as I withdrew with them to the hallway. Both were my warm personal friends and stated frankly that they had been prompted to tender their aid on my account. The reason for this was that I had organized the brakemen’s union and also the switchmen as a national organization, and they naturally felt friendly toward me as they did hostile to Arthur, who had always treated them with cold contempt.

Arthur’s attitude was that the engineers were an exclusive and superior body and that they could not afford to get down to the level of the firemen, brakemen, switchmen, and the rest of the common herd, and it was many years after they were organized and only after they had developed power enough to command respect that he finally deigned to recognize and cooperate with the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen.

Thus was the first wet blanket thrown upon the Burlington strike. The brakemen, after Arthur’s rebuff, refused to come out, but they would render the company no service outside of their regular duties. The switchmen, who have always been the boldest and best fighters in the railway service, ever ready to lend a hand to others, came out in spite of Arthur and were sacrificed to a man for their loyalty to the brotherhood whose chief had contemptuously repelled them.

In the course of the strike a boycott was placed on “Q” cars, and the brotherhood men on other roads refused to handle them. This was the turning point in the strike. The boycott worked with deadly effect.

Then the “Q” officials got busy. Henry B. Stone, the general manager, whose tragic death after the strike seemed to have in it the hand of retribution, secured a federal court injunction restraining the engineers and firemen of other roads from refusing to handle “Q” cars. That brought the issue to a climax. The strike was won or lost then and there.

At this juncture Alexander Sullivan, the then noted Chicago lawyer who had been employed by Arthur and Sargent, appeared at our headquarters and gave warning that if the boycott was not immediately raised the heads of the brotherhoods would be arrested and sent to jail.

Of course I opposed the raising of the boycott, but Arthur and Sargent had full authority and I had none. I was simply present by courtesy as an official associate, being at that time Grand Secretary and Treasurer of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and editor and manager of their magazine.

What happened next fell upon my ears like a thunderclap from a clear sky. Grand Chief Arthur arose and said in solemn tones: “The boycott must be raised, and at once, for I would not go to jail for your whole brotherhood.”

The committee was speechless. The voice of Arthur was supreme. The boycott was declared off and the strike, though it lingered for months, was lost at that moment.

A finer, braver, more loyal and determined army of strikers I have never seen. They had the strike won from the start but were betrayed into defeat through the cowardly and stupid leadership.

Returning to my home at Terre Haute to resume my neglected duties, I was awakened one morning at 4 o’clock by a sub-committee of two engineers, who had been delegated by the general committee of the “Q” strikers to call on me and to return to Chicago and assume direction of the strike. The radical policy I had advocated, and to which Arthur and Sargent were bitterly opposed, suited the committee especially since they had seen the sudden turn the strike had taken.

They still believed it possible to win the day. They insisted upon my return and when I protested that Arthur and Sargent had full authority and I had none at all, and that, moreover, they were firmly set against the policy I favored, they said: “We know that Arthur and Sargent don’t want you but we do, and we know that their policy will lose the strike and that yours will win in.”

One of those two engineers who came to my home that morning was Edward N. Hurley, then an engineer on the Burlington and now chairman of the shipping board under the Wilson administration.

I returned to Chicago on the first train in company with the two engineers. Arthur and Sargent frowned as I entered headquarters. It was plain that I was an intruder there. The committee on the outside had received me with open arms.

Then discord threatened, and with it the cutting off of financial support. The official heads were determined that there should be no radical action and they had the power to enforce their policy. I lingered upon the scene but a short time. It grieved me sorely to see that brave army go down to defeat. But I could not help it, and its recollection is to me one of the tragedies of the class struggle.

Today these engineers, firemen, and switchmen — those who still survive — are scattered over all the western states from the Ohio to the Pacific and they still tell you how the strike on the “Q” might have been won.

The New York Call was the first English-language Socialist daily paper in New York City and the second in the US after the Chicago Daily Socialist. The paper was the center of the Socialist Party and under the influence of Morris Hillquit, Charles Ervin, Julius Gerber, and William Butscher. The paper was opposed to World War One, and, unsurprising given the era’s fluidity, ambivalent on the Russian Revolution even after the expulsion of the SP’s Left Wing. The paper is an invaluable resource for information on the city’s workers movement and history and one of the most important papers in the history of US socialism. The paper ran from 1908 until 1923.