Wilson with a major review of the work and ideas of the 19th century French novelist, with a central reading of Falubert’s L’Education Sentimentale alongside Marx’s Eighteenth Brumaire.

‘Flaubert’s Politics’ by Edmund Wilson from Partisan Review. Vol. 4 No. 1. December, 1937.

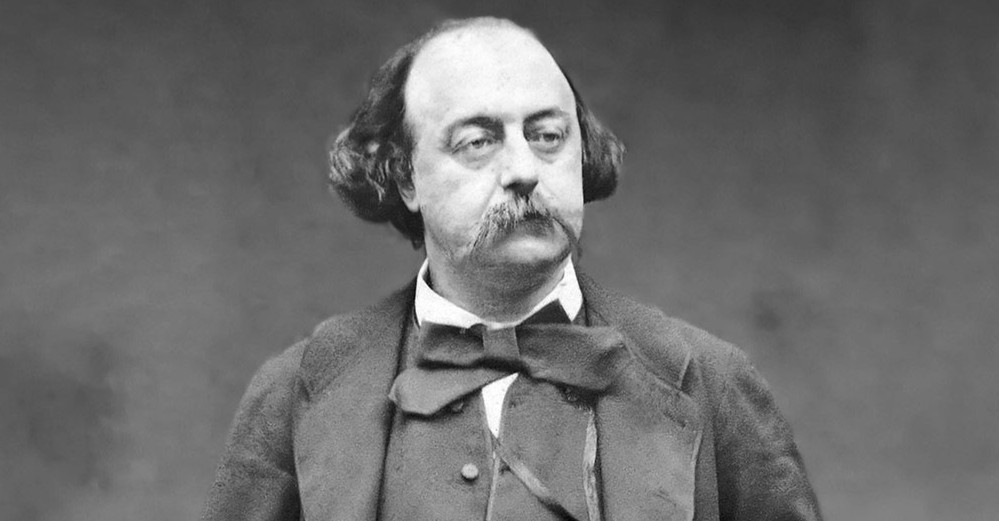

GUSTAVE FLAUBERT has figured for decades as the great glorifier and practitioner of literary art at the expense of human affairs both public and personal. We have heard about his asceticism, his nihilism, his consecration to the search for le mot juste. His admirers have tended to praise him on the same assumption: that he has no moral or social interests. At most, Madame Bovary has been taken as a parable of the romantic temperament.

Really Flaubert owed his superiority to those of his contemporaries—Gautier, for example—who professed the same literary creed, to the seriousness of his concern with the large questions of human destiny. It was a period when the interest in history was intense; and Flaubert, in his intellectual tastes as well as in his personal relations, was almost as close to the historians Michelet, Renan and Taine, and to the historical critic Sainte-Beuve, as to Gautier and Baudelaire. In the case of Taine and Sainte-Beuve, he came to deplore their preoccupation in their criticism with the social aspects of literature at the expense of all its other values; but he himself always seems to see humanity in social terms and historical perspective. His point of view may be gauged pretty accurately from his comments in one of his letters on Taine’s History of English Literature: There is something else in art beside the milieu in which it is practised and the physiological antecedents of the worker. On this system you can explain the series, the group, but never the individuality, the special fact which makes him this person and not another. This method results inevitably in leaving talent out of consideration. The masterpiece has no longer any significance except as an historical document. It is the old critical method of La Harpe precisely turned around. People used to believe that literature was an altogether personal thing and that books fell out of the sky like meteors. Today they deny that the will and the absolute have any reality at all. The truth, I believe, lies between the two extremes.”

But it was also a period in France—Flaubert’s lifetime, 1820-81—of alternating republics and monarchies, of bogus emperors and defeated revolutions, when political ideas were in confusion. The French historians of the Enlightenment tradition, which was the tradition of the Revolution, were steadily becoming less hopeful; and a considerable group of the novelists and poets held political and social issues in contempt and staked their careers on art as an end in itself: their conception of their relation to society was expressed in their damnation of the bourgeois, who gave his tone to all the world, and their art was a defiance of him. The Goncourts in their journal have put the attitude on record: “Lying phrases, resounding words, blarny—that’s just about all we get from the political men of our time. Revolutions are a simple déménagement followed by the moving back of the same ambitions, corruptions and villainies into the apartment which they have just been moved out of—and all involving great breakage and expense. No political morals whatever. When I look about me for a disinterested opinion, I can’t find a single one. People take risks and compromise themselves on the chance of getting future jobs…You are reduced, in the long run, to disillusion, to a disgust with all beliefs, a tolerance of any power at all, an indifference to political passion, which I find in all my literary friends, and in Flaubert as in myself. You come to see that you must not die for any cause, that you must live with any government that exists, no matter how antipathetic it may be to you—you must believe in nothing but art and profess only literature. All the rest is a lie and a booby-trap.” In the field of art, at least, it was possible, by heroic effort, to prevent the depreciation of values.

This attitude, as the Goncourts say, Flaubert fully shared. “Today,” he wrote Louise Colet in 1853: “I even believe that a thinker (and what is an artist if he is not a triple thinker?) should have neither religion nor fatherland nor even any social conviction. It seems to me that absolute doubt is now indicated so clearly that it would be almost an absurdity to want to formulate it.” And “the citizens who work themselves up for or against the Empire or the Republic,” he wrote George Sand in 1869, “seem to be just about as useful as the ones who used to argue about efficacious grace and efficient grace.” Nothing exasperated him more—and we may sympathize with him today—than the idea that the soul is to be saved by the profession of correct political opinions.

Yet Flaubert is a thundering idealist. “The idea” which turns up in his letters of the fifties—”genius like a powerful horse drags humanity at her tail along the roads of the idea,” in spite of all that human stupidity can do to rein her in—is evidently, under its guise of art, none other than the Hegelian “Idea,” which served Marx and so many others under a variety of different guises. There are great forces in humanity, Flaubert feels, which the present is somehow suppressing but which may some day be gloriously set free. “The soul is asleep today, drunk with the words she has listened to, but she will experience a wild awakening in which she will give herself up to the ecstasies of liberation, for there will be nothing more to constrain her, neither government nor religion, not a formula; the republicans of all shades of opinion seem to me the most ferocious pedagogues, with their dream of organizations, of a society constructed like a convent.”

When he reasons about society—which he never does except in his letters—his conceptions seem incoherent. But Flaubert, who believed that the artist should be a triple thinker and who was certainly one of the great minds of his time—was the kind of imaginative writer who works dramatically in images and does not deal at all in ideas. His informal expressions of his general opinions are as unsysstematized and impromptu as his books are well-built and precise. But it is worthwhile to quote a few from his letters because, though they are so very far from formulating a social philosophy—when George Sand accused him of not having one, he admitted it—they do indicate the instincts and emotions which are the prime movers in the world of his art.

Flaubert is opposed to the socialists because he regards them as materialistic and because he dislikes their authoritarianism, which he says derives straight from the tradition of the Church. Yet they have “denied pain, have blasphemed three-quarters of modern poetry, the blood of Christ, which quickens in us.” And: “O socialists, there is your ulcer: the ideal is lacking to you; and that very matter which you pursue slips through your fingers like a wave; the adoration of humanity for itself and by itself (which brings us to the doctrine of the useful in Art, to the theories of public safety and reason of state, to all the injustices and all the intolerances, to the immolation of the right, to the levelling of the Beautiful), that cult of the belly, I say, breeds wind (pardon the pun).” One thing he makes clear by reiteration through the various periods of his life: his disapproval of the ideal of equality. What is wanted, he keeps insisting, is “justice”; and behind this demand for justice is evidently Flaubert’s resentment, arising from his own literary experience, against the false reputations, the undeserved rewards and the stupid repressions of the Second Empire. And he was skeptical of popular education and opposed to universal suffrage.

Yet among the contemporaries whom he admired most were democrats, humanitarians, and reformers. “You are certainly the French author,” he wrote Michelet, “whom I have read and reread most”; and he said of Victor Hugo that Hugo was the living man “in whose skin” he would be happiest to be. George Sand was one of his closest friends. Un Coeur Simple was written for her—apparently to answer her reproach that Art was “not merely criticism and satire” and to show her that he, too, had a heart.

When we come to Flaubert’s books themselves, we find a much plainer picture of things.

It is not true, as is sometimes supposed, that he disclaimed any moral intention. He deliberately refrained in his novels from commenting on the action in his own character: “the artist ought not to appear in his work any more than God in nature.” But, like God, he rules his universe through law; and the reader, from what he hears and sees, must infer the moral system.

What are we supposed to infer from Flaubert’s work? His general historical point of view is, I believe, pretty well known. He held that “the three great evolutions of humanity” had been “paganisme, christianisme, muflisme (muckerism),” and that Europe was in the third of these phases. Paganism he depicted in Salammbé and in the short story Hérodias. The Carthaginians of Salammbé had been savage barbarians: they had worshipped serpents, crucified lions, sacrificed their children to Moloch and trampled armies down with herds of elephants; but they had slaughtered, lusted and agonized superbly. Christianity is exemplified in the two saints’ legends, La Tentation de Saint Antoine and La Légende de Saint Fulien l’Hospitalier. The Christian combats his lusts, he expiates human cruelty; but this attitude, too, is heroic: Saint Anthony, who inhabits the desert, Saint Julien, who lies down with the leper, have pushed to their furthest limits the virtues of abnegation and humility. But when we come to the muflisme of the nineteenth century—in Madame Bovary and L’Education Sentimentale—all is meanness, mediocrity and timidity.

The villain here is, of course, the bourgeois; and it is true that these two novels of Flaubert damn the contemporary world as flatly as the worlds of Salammbé and Saint Anthony have been roundly and dogmatically exalted. But in these pictures of modern life there is a greater complexity of human values and an analysis of social processes which does not appear in the books about the past.

This social analysis of Flaubert’s has, it seems to me, been too much disregarded, and this has resulted in the underestimation of one of his greatest books, L’Education Sentimentale.

In Madame Bovary, Flaubert criticizes the nostalgia for the exotic which played such a large part in his own life and which led him to write Salammbé and Saint Antoine. What cuts Flaubert off from the other romantics and makes him primarily a social critic is his grim realization of the futility of dreaming about the splendors of the orient and the brave old days of the past as an antidote to bourgeois society. Emma Bovary, the wife of a small country doctor, is always seeing herself in some other setting, imagining herself someone else. She will never face her situation as it is, with the result that she is eventually undone by the realities she has been trying to ignore. The upshot of all Emma’s yearnings for a larger and more glamorous life is that her poor little daughter, left an orphan by Emma’s suicide and the death of her father, is sent to work in a cotton mill.

The socialist of Flaubert’s time might perfectly have approved of this: while the romantic individualist deludes himself with dreams in the attempt to evade bourgeois society and only succeeds in destroying himself, he lets humanity fall a victim to the industrial-commercial processes, which, unimpeded by his dreaming, go on.

Flaubert had more in common and had perhaps been influenced more by the socialist thought of his day than he would ever have allowed himself to confess. In his novels, it is never the nobility, who are indistinguishable for mediocrity from the bourgeoisie, but the peasants and working people whom he habitually uses as touchstones to bring out the meanness and speciousness of the bourgeois. One of the most memorable scenes in Madame Bovary is the agricultural exhibition at which the pompous local dignitaries award a medal to an old farm servant for forty-five years of service on the same farm. Flaubert has told us about the bourgeois at length, made us listen to a long speech by a town councilor on the flourishing state of France; and now he describes the peasant—scared by the flags and the drums and by the gentlemen in black coats and not understanding what is wanted of her. Her long and bony hands, with which she has worked all her life in greasy wool, stable dust and lye, still seem dirty, although she has just washed them, and they hang half open, as if to present the testimony of her toil. There is no tenderness or sadness in her face: it has a rigidity almost monastic. And her long association with animals has given her something of their placidity and dumbness. “So she stood before those florid bourgeois, that half-century of servitude.” And the heroine of Un Coeur Simple, a domestic servant who devotes her whole life to the service of a provincial family and gets not one ray of love in return, has a similar dignity and pathos.

But it is in L’Education Sentimentale that Flaubert’s account of society comes closest to socialist theory. Indeed, his presentation here of the Revolution of 1848 parallels in so striking a manner Marx’s analysis of the same events in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon that it is worthwhile to bring together into the same focus the diverse figures of Flaubert and Marx in order to see how two great minds of the last century, pursuing courses so apparently divergent, arrived at identical interpretations of the happenings of their own time.

When we do this, we become aware that Marx and Flaubert started from very similar assumptions and that they were actuated by moral aims almost equally uncompromising. Both implacably hated the bourgeois, and both were resolved at any cost of worldly success to keep outside the bourgeois system. And Marx, like Flaubert, shared to some degree the romantic bias in favor of the past. Karl Marx can, of course, hardly be said to have had a very high opinion of any period of human history; but in comparison with the capitalist nineteenth century he betrayed a certain tenderness for Greece and Rome and the Middle Ages. He pointed out that the slavery of the ancient world had at least purchased the “full development” of the masters and that a certain Antipater of Thessalonica had joyfully acclaimed the invention of the water wheel for grinding corn because it would set free the female slaves who had formerly had to do this work, whereas the bourgeois economists had seen in machinery only a means for making the workers work faster and longer in order “to transform a few vulgar and half-educated upstarts into ‘eminent cotton spinners,’ ‘extensive sausage makers’ and ‘influential blacking dealers’.” And he had also a soft spot for the feudal system before the nobility had revolted against the Crown and while the rights of all classes, high and low, were still guaranteed by the king. Furthermore, the feudal lords, he insisted, had spent their money lavishly when they had it, whereas it was of the essence of capitalism that the capitalist saved his money and invested it, only to save and reinvest the profits.

Karl Marx’s comment on his time was The Communist Manifesto. What is the burden of the great social novel of Flaubert? Frédéric Moreau, the hero of L’Education Sentimentale, is a sensitive and intelligent young man with an income; but he has no stability of purpose and is capable of no emotional integrity. He becomes so aimlessly, so will-lessly, involved in love affairs with different types of women that he is unable to make anything real out of any of them: they trip each other up until in the end he is left with nothing. He is most in love from the very beginning with the virtuous wife of a sort of glorified drummer, who is engaged in more or less shady business enterprises; but, what with his timidity and her virtue, he never gets anywhere with her—even though she loves him in return —and leaves her in the hands of the drummer. Flaubert makes it plain to us, however, that Frédéric and the vulgar husband at bottom represent the same thing: Frédéric is only the more refined as well as the more incompetent side of the middle-class mediocrity of which the promoter is the more flashy and active.

And so in the case of the other characters, the representatives of journalism, art and drama and of the various political factions of the time and the remnants of the old nobility, Frédéric finds the same shoddiness and lack of principle which are gradually revealed in himself—the same qualities which render so odious to him the banker M. Dambreuse, the type of the rich and powerful class of the age. M. Dambreuse is always ready to trim his sails to any political party, monarchist or republican, which seems to have a chance of success. “Most of the men who were there,” Flaubert writes of the guests at M. Dambreuse’s house, “had served at least four governments; and they would have sold France or the human race in order to guarantee their fortune, to spare themselves a difficulty or anxiety, or even merely from baseness, instinctive adoration of force.” “Fe me moque des affaires!” cries Frédéric when the guests at M. Dambreuse’s are complaining that criticism of the government hurts business; but he always comes back to hoping to profit by M. Dambreuse’s investments and position.

The only really sympathetic characters in L’Education Sentimentale are, again, the representatives of the people. Rosanette, Frédéric’s mistress, is the daughter of poor workers in the silk mills, who sold her at fifteen to an old bourgeois. Her liaison with Frédéric is a symbol of the disastrously unenduring union between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie, of which Marx, in The Eighteenth Brumaire had written. After the suppression of the workers’ insurrection during the June days of ’48, Rosanette gives birth to a weakly child, which dies while Frédéric is already arranging a love affair with the dull wife of the banker. Frédéric believes that Mme. Dambreuse will be able to advance his interests. And bourgeois socialism gets a very Marxist treatment—save in one respect, which we shall note in a moment—in the character of Sénécal, who is eternally making himself unpleasant about communism and the welfare of the masses, for which he is apparently ready to fight to the last barricade. When Sénécal, however, gets a job as foreman in a pottery factory, he turns out to be an inexorable little tyrant; and when it begins to appear, after the putting down of the June riots, that the reaction is sure to triumph, he begins to decide, like our Fascists today, that the strong centralization of the government is already itself a kind of communism and that authority is in itself a great thing.

On the other hand, there is the clerk Dussardier, a strapping and stupid fellow and one of the few honest characters in the book. When we first see him he has just knocked down a policeman in a political brawl on the street. Later, when the National Guard, of which Dussardier is a member, turns against the proletariat in the interests of law and order, Dussardier fells one of the insurgents from the top of a barricade and gets at the same time a bullet in the leg, thereby be-coming a great hero of the bourgeois. But Dussardier himself is unhappy. The boy he had knocked down had wrapped the tricolor around him and shouted to the National Guard: “Are you going to fire on your brothers?” Dussardier isn’t at all sure that he oughtn’t to have been on the other side. His last appearance is at the climax of the story, constitutes, indeed, the climax: he turns up in a proletarian street riot, which the cavalry and police are putting down. Dussardier refuses to move on, crying “Vive la République!”; and Frédéric comes along just in time to see one of the policemen kill him. Then he recognizes the policeman: it is the socialist, Sénécal.

L’Education Sentimentale, unpopular when it first appeared, is likely, if we read it in our youth, to prove baffling and even repellent. It sounds as if it were going to be a love story, but the love affairs turn out so consistently to be either unfulfilled or lukewarm that we find ourselves irritated or depressed. Is it a satire? It is too real for a satire. Yet it does not seem to have the kind of vitality which we are accustomed to look for in a novel.

Yet, although we may rebel, as we first read it, against L’Education Sentimentale, we find afterwards that it has stuck in our crop. If it is true, as Bernard Shaw has said, that Das Kapital makes us see the nineteenth century “as if it were a cloud passing down the wind, changing its shape and fading as it goes,” so that we are never afterward able to forget that “capitalism, with its wage slavery, is only a passing phase of social development, following primitive communism, chattel slavery and feudal serfdom into the past”—so Flaubert’s novel plants deep in our mind an idea which we never get quite rid of —the suspicion that our middle class society of business men, bankers and manufacturers, and people who live on or deal in investments, so far from being redeemed by its culture, has ended by cheapening and invalidating culture: politics, science and art—and not only these but the ordinary human relations, love, friendship and loyalty to cause—till the whole civilization has seemed to dwindle.

But fully to appreciate the book, one must have had time to see something of life and to have acquired a certain interest in social as distinct from personal questions. Then, if we read it again, we are amazed to find that the tone no longer seems really satiric and that we are listening to a sort of muted symphony of which the timbres had been inaudible before. There are no hero, no villain, to arouse us, no clowns to amuse us, no scenes to wring our hearts. Yet the effect is deeply moving. It is the tragedy of nobody in particular, but of the poor human race itself reduced to such ineptitude, such cowardice, such commonness, such weak irresolution—arriving, with so many fine notions in its head, so many noble words on its lips, at a failure which is all the more miserable because those who have failed are hardly conscious of having done so.

Going back to L’Education Sentimentale, we come to understand Mr. F. M. Ford’s statement that you must read it fourteen times. Though it is less attractive on the surface than Madame Bovary and perhaps others of Flaubert’s books, it is certainly the one which he put the most into. And once we have got the clue to all the immense and complex drama which unrolls itself behind the detachment and the monotony of the tone, we find it as absorbing and satisfying as a great play or a great piece of music.

The one conspicuous respect in which Flaubert’s criticism of the events of 1848 diverges from that of Marx has been thrown into special relief by the recent events of our own time. For Marx, the evolution of the socialist into a policeman would have been due to the bourgeois in Sénécal; for Flaubert, it is a natural development of socialism. Flaubert distrusted, as I have mentioned in quoting from his letters, the authoritarian aims of the socialists. For him, Sénécal, given his bourgeois hypocrisy, was still carrying out a socialist principle—or rather, his behavior as a policeman and his yearnings toward socialist control were both derived from his tyrannical instincts.

Today we must recognize that Flaubert had observed something of which Marx was not aware. We have had the opportunity to see how even a socialism which has come to power as the result of a proletarian revolution has bred a political police of almost unprecedented ruthlessness and pervasiveness—how the socialism of Marx himself, with its emphasis on dictatorship rather than on democratic processes, has contributed to produce this disaster. Here Flaubert, who believed that the artist should aim to be without social convictions, has been able to judge the tendencies of political doctrines as the greatest of doctrinaires could not; and here the role chosen by Flaubert is justified.

The war of 1870 was a terrible shock to Flaubert; the nervous disorders of his later years have been attributed to it. He had the Prussians in his house at Croisset and had to bury his manuscripts. When he made a trip to Paris after the Commune, he came back to the country deeply shaken. “This would never have happened,” he said when he saw the wreck of the Tuileries, “if they had only understood L’Education Sentimentale. What he meant, one supposes, was that, if they had understood the falsity of their politics, they would never have wreaked so much havoc for their sake. “Oh, how tired I am,” he writes George Sand, “of the ignoble worker, the inept bourgeois, the stupid peasant and the odious ecclesiastic.”

But in his letters of this period, which are more violent than ever, we see him taking a new direction. The effect of the Commune n Flaubert, as on so many of the other French intellectuals, was to bring out the class-conscious bourgeois in him. Basically bourgeois his life had always been, with his mother and his little income. He had, like Frédéric Moreau himself, been “cowardly in his youth,” he wrote George Sand. “I was afraid of life.” And even moving amongst what he regarded as the grandeurs of the ancient world, he remains a moderate modern Frenchman who seems to be indulging in immoderation self-consciously and in the hope of horrifying other Frenchmen. Marcel Proust has pointed out that Flaubert’s imagery, even when he is not dealing with the world of the bourgeois, tends itself to be rather banal. It was the enduring tradition of French classicism which had saved him from the prevailing cheapness: by discipline and objectivity, by heroic application to the mastery of form, he had kept his world at a distance. But now when a working class government had held Paris for two months and a half and had wrecked monuments and shot bourgeois hostages, Flaubert found himself as fierce against the Communards as any respectable “grocer.” “My opinion is,” he wrote George Sand, “that the whole Commune ought to have been sent to the galleys, that those sanguinary idiots ought to have been made to clean up the ruins of Paris, with chains around their necks like convicts. That would have wounded humanity, though. They treat the mad dogs with tenderness but not the people who have gotten bitten.” He raises his old cry for “justice.” Universal suffrage, that “disgrace to the human spirit,” must first of all be done away with; but among the elements which must be given their due importance he now includes “race and even money” along with “intelligence” and “education.”

For the rest, certain political ideas emerge—though, as usual, in a state of confusion. “The mass, the majority, are always idiotic. I haven’t got many convictions, but that one I hold very strongly. Yet the mass must be respected, no matter how inept it is, because it contains the germs of an incalculable fecundity. Give it liberty, but not power. I don’t believe in class distinctions any more than you do. The castes belong to the domain of archaeology. But I do believe that the poor hate the rich and that the rich are afraid of the poor. That will go on forever. It is quite useless to preach the gospel of love to either. The most urgent need is to educate the rich, who are, after all, the strongest.” “The only reasonable thing to do—I always come back to that—is a government of mandarins, provided that the mandarins know something and even that they know a great deal. The people is an eternal minor, and it will always (in the hierarchy of social elements) occupy the bottom place, because it is unlimited number, mass. It gets us nowhere to have large numbers of peasants learn to read and no longer listen to their priest; but it is infinitely important that there should be a great many men like Renan and Littré who can live and be listened to. Our salvation now is in a legitimate aristocracy, by which I mean a majority which will be made up of something other than numerals.” Renan himself and Taine were having recourse to similar ideas of the salvation of society through an elite. In Flaubert’s case, it never seems to have occurred to him that the hierarchy of mandarins he is proposing and his project for educating the rich are identical with the ideas of Saint-Simon, which he had rejected years before with such scorn on the ground that they were too authoritarian. The Commune has stimulated in Flaubert a demand for his own kind of despotism.

He had already written in 1869: “…politics will remain idiotic forever so long as it does not derive from science. The government of a country ought to be a department of the Institute, and the least important of all.” “Politics,” he reiterated in 1871, “must become a positive science, as war has already become”; and, “The French Revolution must cease to be a dogma and become part of the domain of science, like all the rest of human affairs.” Marx and Engels were not reasoning otherwise; but they believed, as Flaubert could not do, in a coming of age of the proletariat which would make possible the application of social science. For Flaubert, the proletariat had been pathetic but too stupid to do anything effective; the Commune threw him into such a panic that he talked about them as criminals and brutes. At one moment he writes to George Sand, “The International may end by winning out, but not in the way that it hopes, not in the way that people are afraid of”; and then, two days later, “the International will collapse, because it is on the wrong path. No ideas, nothing but envy!” Finally, he wrote her in 1875: “The words ‘religion’ or ‘Catholicism,’ on the one hand, ‘progress,’ ‘fraternity,’ ‘democracy,’ on the other, no longer answer the spiritual needs of the day. The dogma of equality—a new thing—which the radicals have been crying up, has been proved false by the experiments of physiology and by history. I do not at the present time see any way of setting up a new principle, any more than of still respecting the old ones. So I search, without finding it, for the central idea on which all the rest ought to depend.”

In the meantime, his work becomes more misanthropic. “Never, my dear old chap,” he had written Ernest Feydeau, “have I felt so colossal a disgust for mankind. I’d like to drown the human race under my vomit.” He writes a political comedy, Le Candidat, the only piece that he has yet composed which has not a single even faintly sympathetic character. The rich parvenu who is running for deputy sacrifices his daughter’s happiness and allows himself to be cuckolded by his wife as well as degrades himself by every form of truckling and trimming, in order to win the election. The audience would not have it; and the leading actor, in the role of the candidate came off the stage in tears. One can hardly blame them: reading the play today, in spite of some amusing and mordant scenes, it proves too horrible to take even from Flaubert.

Then he embarked on Bouvard et Pécuchet, which occupied him—with only one period of relief, when he indulged his suppressed kindliness and idealism in the relatively human Trois Contes—for most of the rest of his life. Here two copyists retire from their profession and set out to cultivate the arts and sciences. They make a mess of them all. The book contains an even more withering version of the events of 1848, in which the actors and their political attitudes are reduced to the scale of performing fleas. When Bouvard and Pécuchet find that everything has “cracked up in their hands,” they go back to copying again. Flaubert did not live to finish the book; but the reader was to have been supplied in the second part with a sort of encyclopedia made up entirely of absurd statements and foolish sentiments extracted from the productions which Bouvard and Pécuchet were to copy.

Bouvard et Pécuchet has always mystified Flaubert’s critics, who have usually taken it as a caricature of the bourgeois like L’Education Sentimentale,—in which case, what would have been the point of doing the same thing over again with everything simply smaller and drier? M. René Dumesnil, the Flaubert expert, believes that Bouvard et Pécuchet was to have had a larger application. The encyclopaedia of silly ideas was to have been not merely a credo of the bourgeois: it was to have contained also the ineptitudes of great men, of writers whom Flaubert admired, and even selections from Flaubert himself. The disastrous experiments of the two copyists were to lead to a general exposure of all human stupidity and ignorance—certainly, in the first part of the book, Flaubert caricatures his own notions about politics and society along with those of everybody else. Bouvard and Pécuchet were to realize the stupidity of their neighbors and to learn their own limitations and to be left with a profound impression of the general incompetence of the human race. They were themselves to compile the monument to human inanity.

If this theory is true—and Flaubert’s manuscripts bear it out—Flaubert had lifted the onus of blame from the bourgeois and for the first time written a satire on humanity itself of the type of Gulliver’s Travels. The bourgeois has ceased to preach to the bourgeois: as the first big cracks begin to show in the structure of the nineteenth century, he shifts his complaint to the shortcomings of humanity, for he is unable to believe in, or even to conceive, any non-bourgeois way out.

Partisan Review began in New York City in 1934 as a ‘Bi-Monthly of Revolutionary Literature’ by the CP-sponsored John Reed Club of New York. Published and edited by Philip Rahv and William Phillips, in some ways PR was seen as an auxiliary and refutation of The New Masses. Focused on fiction and Marxist artistic and literary discussion, at the beginning Partisan Review attracted writers outside of the Communist Party, and its seeming independence brought into conflict with Party stalwarts like Mike Gold and Granville Hicks. In 1936 as part of its Popular Front, the Communist Party wound down the John Reed Clubs and launched the League of American Writers. The editors of PR editors Phillips and Rahv were unconvinced by the change, and the Party suspended publication from October 1936 until it was relaunched in December 1937. Soon, a new cast of editors and writers, including Dwight Macdonald and F. W. Dupee, James Burnham and Sidney Hook brought PR out of the Communist Party orbit entirely, while still maintaining a radical orientation, leading the CP to complain bitterly that their paper had been ‘stolen’ by ‘Trotskyites.’ By the end of the 1930s, with the Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939, the magazine, including old editors Rahv and Phillips, increasingly moved to an anti-Communist position. Anti-Communism becoming its main preoccupation after the war as it continued to move to the right until it became an asset of the CIA’s in the 1950s.

Access to full issue: https://archive.org/details/sim_partisan-review_1937-12_4_1/page/1/mode/1up?view=theater