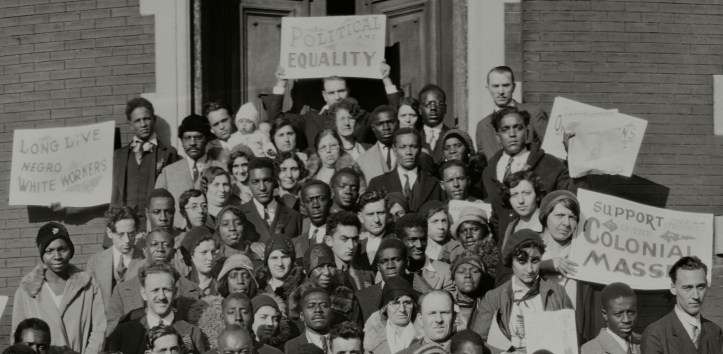

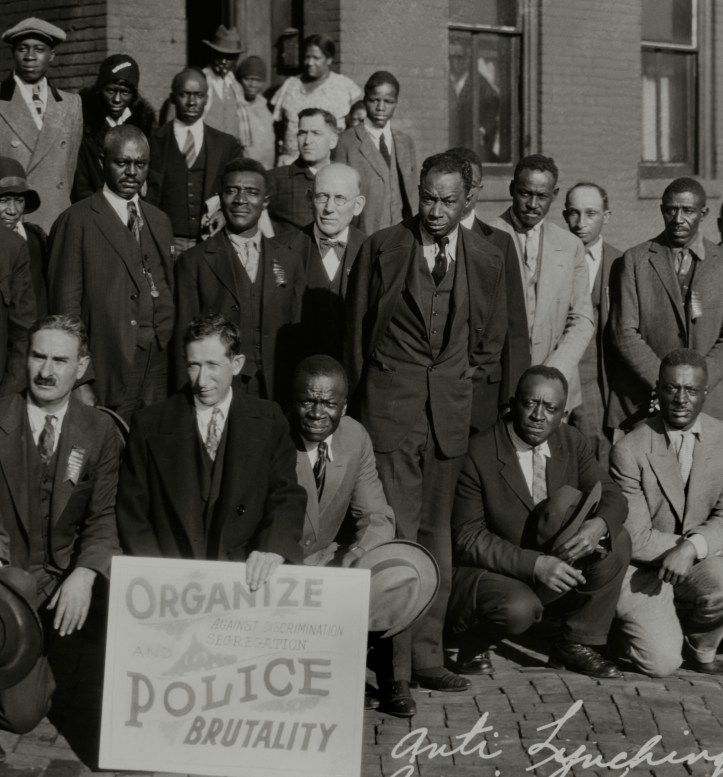

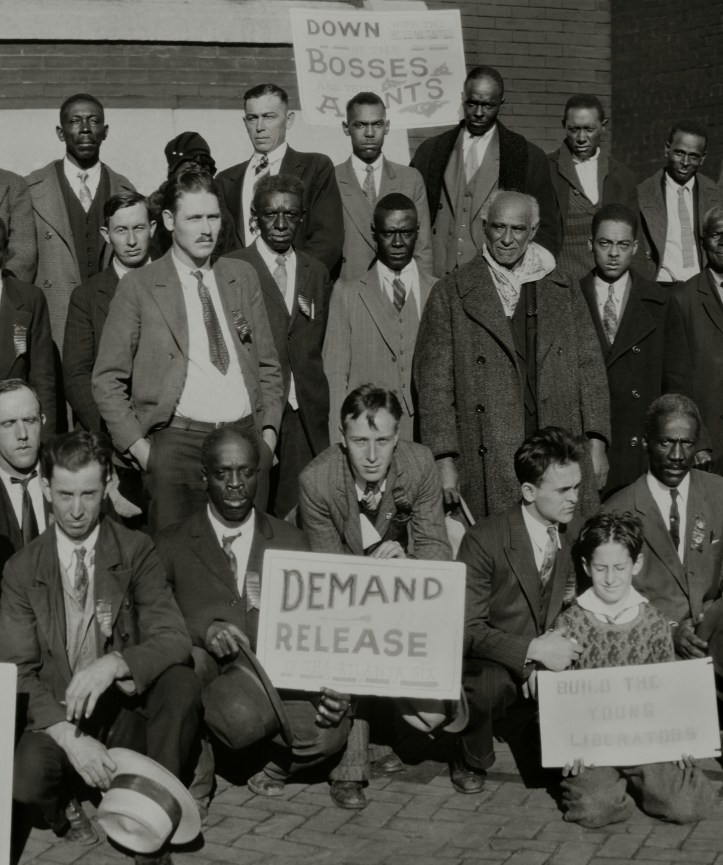

A shift in Communist Party policy in organizing Black workers was inaugurated by the Emergency National Convention Against Lynching in St. Louis during November, 1930. At that meeting the League of Struggle for Negro Rights was founded, replacing the American Negro Labor Congress as the Party’s primary vehicle for Black work. The change of attitude is reflected by the different names, with the new orientation explicitly supporting self-determination and placing the struggle for Black and white workers’ unity in a campaign against white chauvinism in the movement and Jim-Crow in society. The resolution below from the Party’s leadership codifies and amplifies the changed orientation.

‘On Negro Work: Resolution of the Central Committee, Communist Party, U.S.A.’ from The Daily Worker. Vol. 8 No. 71. March 23, 1931.

On the Party’s Work Among Negroes

(1) Thee deepening crisis, which assumes particular sharpness in the South due to the agrarian crisis and drought, with the consequent increase in the national oppression of the Negroes and the steady worsening of their conditions, is already raising as an early perspective the development of mass liberation struggles of the Negro toilers, especially in the South, side by side with, and as a phase of the general rise in the class struggle in the United States.

The bourgeoisie and reformists, as part of their general crisis policy, are greatly increasing their efforts to stimulate chauvinist antagonisms among the white workers against the Negroes, while at the same time Negro misleaders are attempting to arouse the Negro workers against the foreign-born workers, etc., in an effort to dissipate the workers’ growing militancy in futile battles among themselves. The pressure of this bourgeois policy, on the one hand, together with the increased efforts of the Communist Party to attain class unity in the growing struggles, on the other hand, are rapidly uncovering numerous manifestations of white chauvinism in the revolutionary trade unions and other mass organizations, and even in the ranks of the Party itself.

The Party, and the Party fractions in mass organizations, have the task of quickly and decisively overcoming these chauvinist tendencies, as well as all lack of clarity and all underestimation of Negro work, in the course of the most determined efforts to unite the Negro and white workers in the struggles against the bourgeois offensive and for equal rights for the Negroes.

2) The Party has still been insufficiently prepared ideologically for its tremendous tasks in the field of Negro work. In the October Resolution of ECCI, the following statement was correctly emphasized:

“The Party has not yet succeeded in overcoming in its own ranks all underestimation of the struggle for the right of self-determination and still less succeeded in doing away with all lack of clarity on the Negro question.”

This statement still remains in full force, despite certain improvements in our work since the 12th Party plenum. A basis was laid in the discussions at the Plenum for the correction of these shortcomings. But the discussions in the units and the practices of the Party since the 12th Plenum show that much confusion and underestimation still remain to be overcome.

This has not been met with sufficiently timely or energetic action, or by sufficient self-criticism, especially of the serious errors in practical work, by the leading committees of the districts or even by the Politburo itself. The chief weaknesses, which must be immediately corrected, lie in the failure to guide and strengthen the Negro departments sufficiently and in the failure to work out a plan of mass work on the Negro field which alone could furnish the foundation for a sharper struggle to clarify the Party and to overcome all confusion and wrong tendencies in our Negro work.

(3) In addition to this confusion and underestimation, and partly as a result, a number of serious errors, and even dangerous opportunist tendencies, have recently shown themselves in Negro Work.

In the first place there are the mistaken conceptions and proposals with regard to the League of Struggle for Negro Rights.

Some comrades, disregarding the correct policy put forth at the St. Louis convention of the LSNR, and continuing the practices followed with regard to the old ANLC, tended in practice to transfer the leading role of the Party, in the struggle for Negro rights to the LSNR, to look upon the LSNR as a substitute for the Party on the Negro field and to relegate all work among Negroes to Negro comrades and to the LSNR.

These tendencies clearly reflect an opportunist underestimation of the importance of Negro work and an evasion of the Party’s leading role which could easily become a cover for chauvinist tendencies in the Party and the revolutionary mass organizations. They also lead to a failure to bring forward Negro demands in strikes and in unemployment struggles, leaving such demands only to the LSNR.

At the same time there developed among certain comrades, partly as a reaction to the wrong tendencies just cited, and partly because of the insufficiently sharp struggle against chauvinist tendencies in the Party and the unions, an opposition to the correct program of the St. Louis convention and, as an outgrowth of this opposition, proposals for the liquidation of the LSNR. The roots of their wrong proposals are clearly shown by the following quotation:

“The organization (the LSNR) cannot hope to gain sufficient white non-Party workers to change its Jim Crow character. It is clear that when a white worker is sufficiently developed to not only understand that the struggles of the Negro workers are at the same time the struggles of the white workers, but also takes a leading part in the struggles of the Negroes, such a worker is a fit candidate for the Communist Party.”

Such a conception, while appearing to be “left,” is actually a sectarian conception which attempts to limit the struggle for Negro rights to Negro and to white members of the Communist Party. This conception makes more difficult the struggle against the right opportunist tendencies everywhere shown in practice and is itself an opportunist underestimation of the possibility of overcoming the chauvinist tendencies among the white workers in the course of tire now sharpening class struggles and of drawing the broad masses of workers, Negro and white, into common struggle against the capitalist offensive and for equal rights.

Some comrades, also seeing no possibilities of drawing white workers, except Communists, into the struggle for Negro rights, have developed the incorrect position that the “Liberator” is not the leading organ of the struggle for Negro rights, but a “Negro paper” catering only to Negro workers. The tendency to consider the “Daily Worker” as the “white paper” and the “Liberator” as the “Negro paper” is a further indication of sectarian tendencies. It must be recognized, however, that the weakness of the Daily Worker In carrying forward the struggle for Negro rights is one of the causes of the development of the wrong tendency.

These opportunist tendencies, both right and “left,” must be sharply rejected and quickly overcome both in the theory and practice to prevent the possibility of a serious set-back in our mass work, through failure of our efforts to unite the Negro and white workers in joint struggle for Negro rights.

(4) A second serious weakness is in our struggle against white chauvinism. While this has been strengthened in recent months, it has not kept pace with the growing efforts of the bourgeoisie to create white chauvinist antagonisms against Negroes, and thereby create division between the Negro and white worker. In fact, the very increase in the Party’s activities in Negro work has brought to light many cases of chauvinism in all sections of the country without a sufficiently energetic and simultaneous reaction in the Party to the need for greatly widening the ideological struggle to clarify the Party in connection with mass struggles against chauvinism and for Negro rights.

The weaknesses of the Party in this respect have also given rise to opportunist conceptions. Some comrades sharply retreated from all struggle against white chauvinism under cover of counter-charges of “black chauvinism,” narrow nationalism,” etc. They drew a line between such a struggle in the Party and that among the masses, one comrade expressing the fear that an “over-emphasis” on “every little manifestation” of chauvinism in the Party might hamper the recruiting and holding of Negro workers in the Party. Whereas, in fact, it is just such an opportunist glossing over of chauvinist tendencies which would destroy the Negroes’ confidence in the Party.

At the same time certain other comrades, seeing these tendencies to retreat, as well as an insufficiently sharp struggle in general against chauvinist tendencies, tended also to make an opportunist separation between the inner-Party struggle and the mass struggle against chauvinism.

The representatives of the first tendency in substance proposed a liquidation of the inner Party struggle against chauvinist tendencies and a concentration on the mass struggle for equal rights.

The representatives of the second tendency argued in substance that, first, all chauvinist tendencies had to be completely eliminated from the Party before mass work could be undertaken, one comrade stating that now she could not propose a Negro member for the Party because of the existing chauvinist tendencies.

These wrong tendencies must be overcome, primarily in the course of the widest mass struggles for equal rights, while at the same time making every effort to clarify the Party on the Negro question.

(5) To lay the basis for overcoming the confusion. wrong practices and opportunist conceptions in Negro work, the Politburo, first, reasserts the correctness of the line of the St. Louis convention which created the LSNR. The opportunist deviations in practice from that line must now be decisively corrected in every district. The Communist Party, in all cases, is to retain its leading role in the struggle for Negro rights. The LSNR must not become a substitute for the Party. Negro work must not be relegated to the LSNR or become the special task of Negro comrades. On the contrary, with the Party taking the leading role in all of its activities, as well as specifically on the Negro field, in struggle for Negro rights, the LSNR, in addition to its chief immediate task of building the “Liberator,” must become an auxiliary mass organization (groups around the “Liberator,” affiliated groups supporting the aims of the LSNR, etc.) having the task of aiding the Party in rallying the white and Negro workers in the struggle against segregation, Jim Crowism, lynchings, and for equal rights.

In recruiting activities the principal emphasis shall be placed on drawing the Negro workers into the revolutionary TUUL unions and the Party, and in no case must the LSNR be looked upon, either in theory or practice, as a sort of a separate body for the Negroes. Special efforts, however, must be made to recruit while workers into the LSNR by showing the impossibility of the workers making progress in their struggles so long as the white workers tolerate boss-class terror against the Negroes, The Liberator should remain the organ of the struggle for Negro rights, exposing all enemies of Negro liberation, both white and black, and rallying and organizing both Negro and white toilers into the LSNR. It should support the mass campaign of the Communist Party, and especially of the TUUL and the Unemployed Councils, but primarily from the viewpoint of the struggle of the Negroes for national liberation.

(6) Especially now, because of the growing persecution of the Negroes and of the increased efforts of the white and Negro bourgeoisie and reformists to turn the white workers against the colored workers, the colored against the foreign-born, etc., it is necessary to redouble our efforts to secure leadership of the growing Negro liberation movement, linking it up with the general struggle of the workers against the bourgeois offensive, by carrying through the following measures:

(a) In connection with all of the mass activities of the Party, Negro work must be brought into the foreground. Negro work must include, not only the recruiting of Negro members for the Party much better than in the past, but must be conceived of primarily as the development of mass struggles for Negro rights. In the work among the unemployed it is necessary to raise sharply and concretely all discrimination against Negroes in the distribution of relief, persecution of Negro unemployed by the police, etc.; in the work at the shops and factories it is necessary to expose all discrimination against Negroes (district work, lowest wages, etc.); and likewise in all other mass activities. These concrete struggles and demands developed in connection with the fight at a given bread-line, flop house, charity institution, factory or mine, or against a particular city administration, must be the starting point in arousing the masses, white and colored, for the still broader fight against lynching, segregation, Jim-Crowism, and for equal rights (in the South for confiscation of the landowners’ land for the Negro tenants; state unity of the “Black Belt,” and the right of self-determination). The Negro Department of the Central Committee and those in the districts must immediately give attention to the working out of such programs of action as will make the struggle for Negro rights an integral part of the Party’s mass activities.

In this connection it is necessary to strengthen the Negro departments by adding to them leading comrades with mass experience. The district bureaus must immediately check up on the activities of the district Negro departments and immediately take such steps as are necessary to make it possible for them to broaden and develop the mass activities of the Party in the Negro field. Simultaneously with these measures and in conjunction with the program of mass activities, decisive steps are to be taken to overcome all remnants of white chauvinism still remaining in the Party. This shall be done by a wide ideological campaign against white chauvinism and by efforts to clarify the Party on the Negro question in accordance with the several Comintern documents. The struggle against chauvinism must include the most decisive disciplinary measures where necessary.

(b) The Party press, as well as the papers of sympathetic mass organizations, must give much more attention and aggressive leadership than heretofore to the struggle for Negro rights, to the ideological campaign against white chauvinism and to the clarification of the Party and the masses on the Negro question. Wide exposures shall be systematically organized of the living and working conditions of the Negroes, the persecution of the Negroes by the white capitalists and landlords (citing specific cases), the chauvinist theories and practices of the white bourgeoisie and reformists, the misleading segregation theories of the petty capitalist Negro leaders, the lessons and experiences in the struggles for Negro rights, etc. These exposures shall be planned in such away as to become the means of drawing the masses of Negro toilers into the Party’s mass activities and of drawing the masses of white workers into the struggle for Negro rights.

(e) In connection with the efforts of the Central Committee to make a turn in the work of the Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland and Pittsburgh districts, special attention must be given by the C.C. representatives to the development of Negro work especially among the workers in the basic industries in those districts (mining, steel, auto) where tens of thousands of Negro workers are employed and where the issue of Negro rights becomes a burning question, daily affecting all workers. In the programs of action and the plan of work drawn up in these districts, Negro work must be specifically and concretely dealt with in connection with the work among the unemployed and the building of the TUUL unions.

(d) The Party fraction in the L.S.N.R. shall immediately take such steps as are necessary to insure the regular publication of the “Liberator” as a weekly beginning with April 15th. At the same time, and in connection with the launching of the “Liberator” as a weekly, an energetic circulation drive shall be immediately planned and carried through with the objective of 10,000 new subscribers for the “Liberator” by June 1st. The Party is to be fully mobilized to aid in carrying through the circulation drive, primarily in connection with the mass activities of the Party among the unemployed and at the shop and factories. L.S.N.R. groups for the support of the “Liberator” should be organized in the shops and neighborhood. Such groups, in addition to their major task of establishing the “Liberator” as a popular, mass organ of the struggle for Negro rights, should aid the Party in rallying the workers, white and colored, for struggle against all forms of persecution, segregation, lynching, Jim-Crowism, etc., but in no case becoming a substitute for the Party, which at all times must retain its leading role in the struggle for full equality, and in the South, for the right of self-determination.

e) The national and district fraction in the TUUL should immediately bring forth well considered proposals for a widespread strengthening of the Negro work in the TUUL and in all affiliated organizations. The action of the last Executive Board meeting in creating Negro departments in the National Office of the TUUL and in the Miners’, Metal, Marine, and Needle Unions is already a forward step. It is now necessary for the leading fraction to see that real programs of action are developed for the recruiting of Negro workers in all the activities of the unions and for the development of the struggle for Negro rights, beginning by raising partial demands in connection with every form of discrimination or persecution in the shops or mines, or among the unemployed. In all strike struggles the demands of the Negro workers for complete equality must be brought forward and the white workers, especially, must be taught the necessity of uncompromisingly fighting for these demands as a condition for strike settlements, this close linking up of strike demands with those for equal rights being one of the most effective means of undertaking the mass struggle against the chauvinist ideas and practices still existing among many white workers.

The chief immediate task of the TUUL on the field of Negro work is the energetic pushing forward of the work already begun by the appointment of a special organizer at the recent Board meeting for the organization of the Agricultural Workers’ Union in the “Black Belt” of the South. The Party fraction must keep a close check on the programs of the work there, especially with regard to the working out of a program of partial demands which can be the starting point for the development of broader struggle for the land for the Negro tenants and laborers, the state unity of the “Black Belt” and for the right of self-determination.

(f) The Negro department of the Central Committee shall immediately give consideration to all phases of the work (Party, TUUL, Unemployed Councils, as well as ILD, WIR, and other mass organizations) with the objective of bringing about a decisive turn in the Party’s work on the Negro field. The Politburo will make the closest check-up on the work of the department, both of the Central Committee and the districts, and of the leading fractions in all mass organizations to aid them in developing the work and to see that all decisions are energetically and thoroughly carried through.

March 16, 1931.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924. National and City (New York and environs) editions exist.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1931/v08-n071-NY-mar-23-1931-DW-LOC.pdf