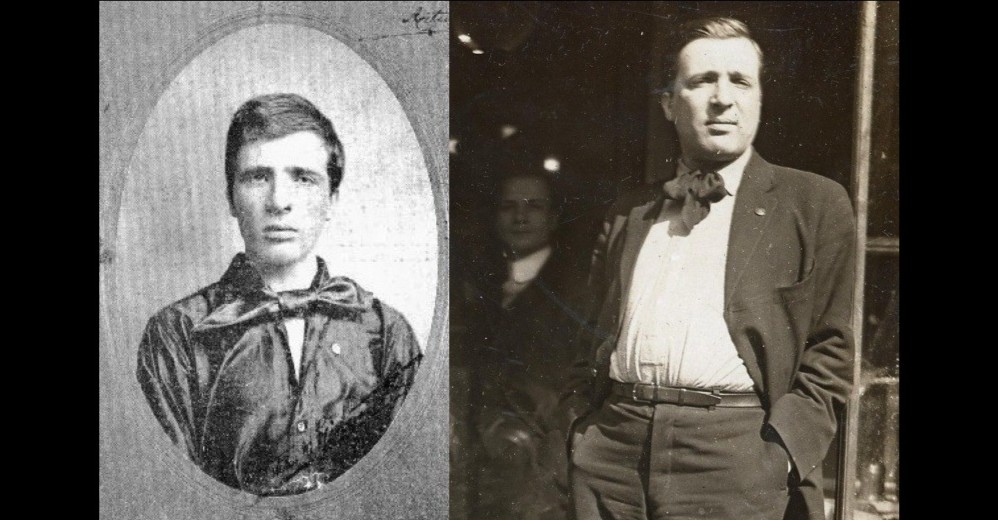

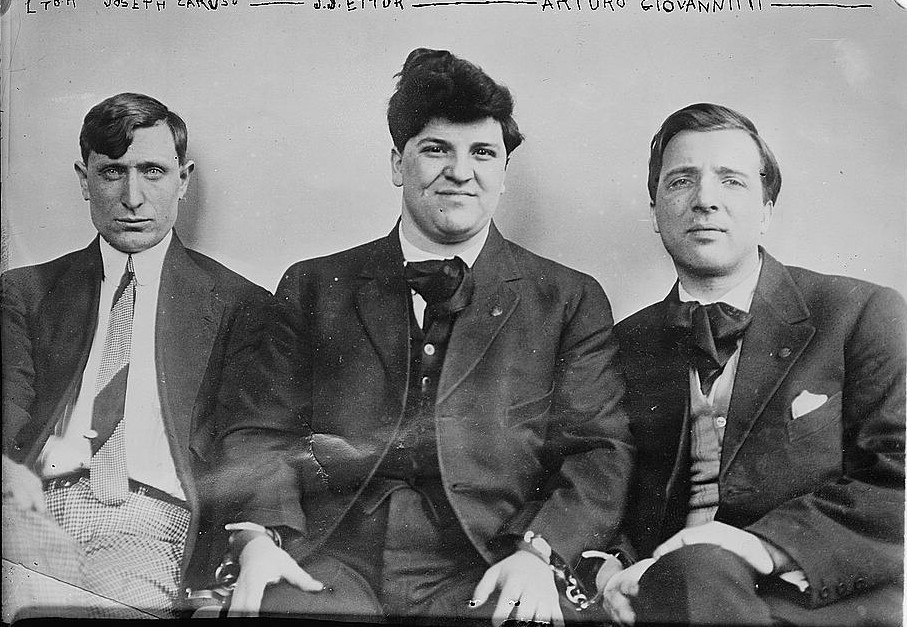

Giovanitti’s poems are a marvelous window into, and reflection of, the effervescence of U.S. radicalism in he first decades of the last century and graced many of the era’s finest journals. His activism in 1912’s Lawrence Strike led him to be charged with murder along with Joseph Ettor, for which he potentially faced death. Ettor, Giovannitti, and Joseph Caruso were eventually acquitted of the murder of Lawrence striker Anna LoPizzo, shot by police during a confrontation on the picket line. His poems written in jail brought him to national prominence and would be released as ‘Arrows in the Gale.’ Here, Leonard Abbott speaks to the potency of his story.

‘The Social Significance of Arturo Giovannitti’ by Leonard D. Abbott from Wilshire’s Magazine. Vol. 17 No. 2. February, 1913.

OF all the men in this country thrown up into public view by the seething, bubbling social discontent of the twentieth century, none is more interesting than Arturo Giovannitti, the young Italian who, with Joseph Ettor, was acquitted a few weeks ago of murder in connection with the Lawrence strikes. He is not the usual type of Labour agitator. The usual type is not a very complex one. Given a rough experience in the school of hard knocks, a close acquaintance with the struggles of the poor to keep a little ahead of starvation, one fixed idea such as the Socialist implant with their gospel of the class war, a certain or uncertain amount of book-education and a considerable degree of dynamic power and natural courage, and the Labour leader is in most cases fairly well accounted for. But in Giovannitti there is something else. He has the soul of a great poet, the fervour of a prophet, and, added to these, the courage and power of initiative that mark the man of action and the organiser of great crusades.

He is but twenty-eight, and he has been in this country but twelve years. Near the close of his trial he made before the court the first speech he has ever made in the English language. It held all hearers spellbound. “In twenty years of reporting,” said a veteran reporter afterwards, “I have never heard the equal of that speech.” Slender, pale, trembling, his voice vibrant with emotion, his eyes welling with tears, “courteous always rather than assertive,” he began as follows: “So solemn is this moment, so full with clashing emotions am I now, that I do not know whether I ever will conclude what I have to say.” For twenty minutes he “spoke like one in the crisis of passion,” and a long hush followed his conclusion, broken by the sobs of men as well as women. Some of the reporters were busier choking down their feelings than making copy, but they have given us an apparently literal report of the peroration:

“I have a wife who loves me, a mother who loves me, an ideal that I love. Life is so wonderful. I feel the passion of living. It is sweet to live. JI do not want to die, to go away as a martyr. Though life is dear to me, there is something holier and grander; that is my conscience and loyalty to my comrades and my cause. If you say that we shall live, I want to say that in the next strike that breaks out in the country where we are needed, there will Joe Ettor and myself go. We will go our humble way, soldiers in the mighty army of workers of the world. If it be that our hearts must be stilled in the same electric chair as wife murderers and homicides; if our hearts be that black, you think—then to-morrow we will pass into a greater judgment, into the presence of the Almighty, and history will give its last word to us.”

Giovannitti was never accused of committing murder himself. It was held that he and Ettor uttered inflammatory speeches, the effect of which was a riot, in which an Italian woman was shot and killed. He steadily denied ever having favoured violence. All his speeches during the strike were in Italian, and but one sentence was testified to—by two private detectives, who said they had lost their notes—that seemed to counsel the use of physical force. This sentence Giovannitti positively denied having uttered, and the jury evidently believed him. But it is certain that he is one of the leaders of the most radical organisation—the Industrial Workers of the World—that has grown out of the Labour movement. His utterances ring with defiance of the whole “capitalist class,” and if he fails to urge his followers to use force, it is probably because he considers the use of force to be as yet inexpedient.

Giovannitti is a social portent, all the more so because he is far removed from the criminal type. He has come to his present extreme views by way of the pulpit and the work of a Christian missionary. He was born in Campobasso, a city of thirty or forty thousand inhabitants in the province of Abruzzi, Italy. His father is a physician and a doctor of chemistry. One of his brothers is a physician and another a lawyer. The social standing of the family is good, and they remain loyal to the son who is in this country. Arturo himself received a fair degree of education in the public schools and lycées of that country. Before he was twenty he came to the new world, going first to Canada. For a time he wielded a pick in a coal mine in the Dominion, and it was there probably that the seeds of his resentment against the industrialism of to-day were planted. Our coal mines seem to have planted many such seeds. While he was studying the English language in Montreal, a Presbyterian minister there, in charge of an Italian mission, died, and Giovannitti was asked to take his place. For months he conducted the mission, and, evidently choosing the ministry as a career, he began to attend a Presbyterian theological school. In 1904, being then twenty years of age, he received a call to Brooklyn to take charge of a Presbyterian mission there. “I was not exactly a minister,” he explains, “but a sort of missionary. I preached to the people on Sundays and taught them during the week.” Still bent on entering the regular ministry, he entered the Union Theological Seminary and also registered at Columbia University. But the course of study of a theological school does not seem to have suited the tropical nature of this dreamer and poet. He stalled at the study of Hebrew. It was, he modestly observes, “a little too strong for my capacities.” A call to conduct an Italian mission in Pittsburg coming to him, he gave up the seminary course, and for eight months carried on his mission labours in the Smoky City.

Three Protestant missions, therefore, were conducted by this man, now a leader in a movement which blazons to the world its banners bearing the legend:

“NO GOD, NO MASTER.”

In Pittsburg he seems to have come, for the first time, into close contact with the Socialists, and to have espoused their cause. The authorities connected with his mission objected to his rapidly-growing activities in behalf of Socialism. As a consequence he severed his relations with the mission, and in 1911 returned to New York. This is probably the time when he began to drop God out of his programme. There were nights when he slept on a bench in City Hall Park. Then he got work as a bookkeeper, and later was employed on an Italian newspaper, Il Proletario, later becoming the editor. His room on West Twenty-Eight Street became a sort of centre of the “intellectuals” of various nationalities, who engaged in radical discussions of religion, art, literature and political economy. Here he met Ettor and others of the Industrial Workers. When the strike was called in the Lawrence mills he had become a full-fledged radical, and was summoned there, his special task being to organise the work of relief for the strikers’ families. He declares that the disorder there would never have occurred if the city authorities had not lost their heads completely. “Eight or nine good Irish ‘cops’ from New York,” he says, “would have handled the situation without calling any militia.” Journals like the Boston Transcript, the Springfield Republican and the New York Journal of Commerce take much the same view. Says the last-named paper concerning the subsequent trial of the Labour leaders: “In any riot in which weapons are used, either by the rioters or by those trying to suppress the mob, somebody is liable to be killed; but there was no reason to believe that killing was a deliberate purpose of the leaders, much less that they could be held directly responsible for the accidental shooting of a woman who was among the rioters as an act of murder. Their conviction under the circumstances would have been rank injustice.”

The whole course of the authorities in the Lawrence strike is generally condemned in influential papers. The New York World seems to voice the general opinion in the following words:

“Woollen Trust sovereignty in Lawrence committed many outrages and follies during the strike. It needlessly called out the militia. It asked the State’s Attorney for a ruling, which he refused, that a speech in Lowell was an interference with military operations in Lawrence. It broke its promise of clemency to men in custody when the strike stopped. It arrested children for preparing to leave town with their parents’ consent, Possibly without its knowledge, but in its behalf, dynamite was planted. Of such stupidity was born the arrest of the three men who were yesterday acquitted. Against Ettor and Giovannitti there was no evidence whatever. Their connection with the crime charged was scarcely a question of fact so much as it was a strained interpretation of the law. They had counselled order. They were far away when Anna Lopizzo was killed.”

A careful review of the trial is made in The Survey (organ until a few days ago of the Russell Sage Foundation) by James P. Heaton. He says that the belief that the charge of murder was “a trumiped-up charge,” brought as a piece of anti-strike tactics to get Ettor and Giovannitti out of the way, “has been shared by attorney, newspaper-men, ministers and students of public affairs who have followed the proceedings.” That the conduct of the trial and its result was a vindication of the probity and judicial acumen of the court was attested by Ettor himself at the conclusion. Even radical papers in Italy, where Giovannitti in the meantime, while in gaol, had been nominated as a member of the Chamber of Deputies, expressed admiration for the court that conducted the case.

For ten months the two men were lodged in gaol, and for a little less than two months the trial was in progress. Thus, says the New York Call, a year of their lives was stolen from them and wasted. No statement could be farther from the mark—so far, at least, as Giovannitti is concerned. We do not refer now to what seems to be the fact, that the attorneys for the two men were themselves responsible for the long delay in the trial; but we refer to the more important fact that this gaol experience of Giovannitti’s has given to the world one of the greatest poems (perhaps more than one) ever produced in the English language. It challenges comparison with the “Ballad of Reading Gaol,” by Wilde, and is fully as vital and soulstirring as anything Walt Whitman ever produced. “The Walker” is its title, and we gave extracts from it in our November number. It was published in full in the International Socialist Review, and the Springfield Republican recently reprinted it in part, giving two and a-half columns to it. It is published in book-form. One of these other poems, entitled “The Cage,” not yet published, is thought by Giovannitti’s friends to surpass “The Walker.” He produced at least five prison poems, some of them in rhyme and rhythm, which show many technical defects, some in Whitmanesque style. One of them, on Rodin’s statue of The Thinker, has the following stanza, showing how far the author has drifted from former theological moorings:—

Beyond your flesh and mind and blood,

Nothing there is to live or do.

There is no man, there is no God,

There is not anything but you.

“The Walker” is more than a poem.

It is a great human document. It begins as follows:—

“I hear footsteps over my head all night.

“They come and they go. Again they come and again they go all night.

“They come one eternity in four paces and they go one eternity in four paces, and between the coming and the going there is Silence and the Night and the Infinite.

“For infinite are the nine feet of a prison cell, and endless is the march of him who walks between the yellow brick wall and the red iron gate, thinking things that cannot be chained and cannot be locked, but that wander far away in the sunlit world in their wild pilgrimage after destined goals.

“Throughout the restless night I hear the footsteps over my head.

“Who walks? I do not know. It is the phantom of the gaol, the sleepless brain, a man, the man, THE WALKER.”

Here is another extract equally graphic and poignant:—

“Wonderful is the holy wisdom of the gaol that makes all thinks the same thought. Marvellous is the providence of the law that equalises all even in mind and sentiment. Fallen is the last barrier of privilege, the aristocracy of the intellect. The democracy of reason has levelled all the two hundred minds to the common surface of the same thought.

“I, who have never killed, think like the murderer;

“I, who have never stolen, reason like the thief;

“I think, reason, wish, hope, doubt, wait like the hired assassin, the embezzler, the forger, the counterfeiter, the incestuous, the raper, the prostitute, the pimp, the drunkard—I—I who used to think of love and life and the flowers and song and beauty and the ideal.

“A little key, a little key as little as my little finger, a little key of shiny brass.

“All my ideas, my thoughts, my dreams are congealed in a little key of shiny brass.

“All my brains, all my soul, all the suddenly surging latent powers of my life are in the pocket of a white-haired man dressed in blue.

“He is powerful, great, formidable, the man with the white hair, for he has in his pocket the mighty talisman which makes one man cry and one man pray, and one laugh, and one walk, and all keep awake and think the same maddening thought.”

This is the sort of thing that Giovannitti’s year in gaol has produced. It was cheap at the price. Both Giovannitti and Ettor spent their time while in confinement in study, the gaoler giving them access to a well-stocked library. Giovannitti began with Taine’s “English Literature.” Then he took up a popular work on the history of literature in general, in four volumes. Then he began on an annotated edition of Shakespeare, who speedily became his favourite author. He dipped deeply into Carlyle and Balzac, Shelley and Byron, the rebellious note of the two poets being especially admired. Kant’s “Critique of Pure Reason” was another work read.

Such is the man we have called a social portent. For it is surely an ominous thing that a young man of good family, well educated, markedly religious by nature, coming to this land in search of freedom and opportunity, actively associated with the Church in its missionary work among the poor, should in a few years be transformed by his experiences into an extreme revolutionary, bitter against authority of all kinds, flouting the Constitution and denying God. If there is such a thing as a social portent, Arturo Giovannitti is one.

Wilshire’s Magazine began as The Challenge, and was one of the most successful Socialist publications in U.S. history. Personally published by Gaylord Wilshire (of Wilshire Blvd. fame) in Los Angeles the magazine, like the Appeal to Reason, was aligned, but independent of the Socialist Party, and not on its ‘Marxist’ wing, its politics more closely resembled the Appeal’s Populism, although it was increasingly sympathetic to industrial unionism putting it at odds with the Party’s right.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/details/wilshires-magazine_1913-02_17_2/page/n2/mode/1up?q=%22arturo+giovannitti%22&view=theater