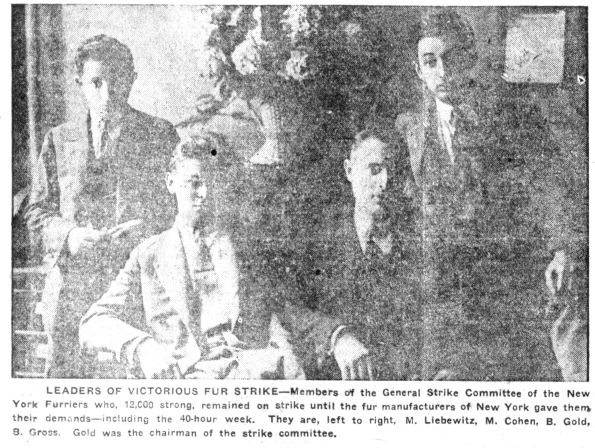

While the ‘Roaring 20s’ generally saw a retreat of militant strikes, an exception was the 1926 general strike of New York’s largely Jewish, many radical, fur workers led by Ben Gold, a Communist and manager of the Joint Board of fur unions. Moissaye Olgin with the story.

‘The Fur Workers Strike’ by Moissaye J. Olgin from New Masses. Vol. 1 No. 4. August, 1926.

ABOUT four years ago, a group of young workingmen entered the office of a labor paper in New York, requesting that a vigorous stand be taken editorially against sinister practises in their labor union. They were young, strong and impetuous, and there was in their expression that peculiar earnestness, almost gravity, almost painful concentration, which so often marks deeply convinced rebels. Still, the editor hesitated. The practises referred to in the workers’ statement were too appalling to be taken in a matter-of-fact way. The editor demanded proof. The workers produced a number of witnesses, eye-witness depositions and other evidence to the effect that beating, slugging, and otherwise maltreating recalcitrant union members was a day-by-day practise of the union administration. The boys who came to the editorial rooms were headed by Ben Gold and Aaron Gross. The union referred to was the New York local of the International Fur Workers’ Union of the United States and Canada. The paper was the Jewish Daily Freiheit.

Further insight into the affairs of the union disclosed that the Furriers’ Union was a name rather than a reality, a group of offices and office-holders rather than a phalanx of organized workers. The average union member had no chance to express his opinion. The duty of the average member was to pay dues and keep mum. Union meetings were held on very rare occasions and only to ratify actions of the administration where ratification was unavoidable. The opposition was completely stifled. The strength of the union leaders lay in a group of professional sluggers paid from the union treasury to “keep order.” The prevailing formula at union meetings was, “Sit down or you will be carried out.” And they did “carry out” more than one dissatisfied member who dared to ask pertinent questions.

Several months later, that same Gold who was known as a representative of the opposition enjoying wide recognition among the mass of the workers, was attacked by union sluggers, slashed, cut and bruised severely, and thus warned to refrain from “subversive activities.” Gold had to be removed to a hospital whence he emerged several weeks later.

This, then, was the picture: A hidebound bureaucracy above, heedless of anything but its own maintenance of office; a disgruntled but intimidated and almost wholly unorganized mass of workers below; a class-conscious rebellious opposition fully cognizant of the harm done by these far too typical methods of union “activities,” painfully conscious of the necessity of reorganizing the union on a fighting basis, full of courage, daring, ability to sacrifice, yet powerless and helpless in the face of a sheer physical force which struck out recklessly, giving no quarter.

Thus the very aim of union organization was defeated. Where there is no union, there can be no fight for better conditions. Nobody felt it with more gratification than the fur manufacturers’ associations who slowly but consistently lowered the standard of labor conditions and the wages of the workers. The agreement was flagrantly broken, the pledges brazenly violated, and as time passed the workers realized that their seasons became shorter, their working hours longer, their pay envelopes thinner, their asthma and other occupational diseases more devastating, their spirits in consequence, lower.

But was there enough fighting spirit, enough class consciousness, enough cohesive power, among those coughing, spluttering, wheezing workers to break out of this lethargy? This is commonly asked not only in relation to the furriers, but of every group of workers throughout the United States. Isn’t it true that the American worker is backward, that he has not developed that peculiar hate and mistrust towards capitalism which marks the labor movement of the European countries? Developments within the Furriers Union answered these questions, at least as far as the fur workers of New York City are concerned.

A wise man said that one may gain a victory by means of bayonets, but they are inconvenient to sit on. Notwithstanding the iron rule of the bureaucracy, notwithstanding the rare ability of the administration to count ballots in a manner that would perpetuate its own tenure of office, the rank and file rebellion became so sweeping, so universal and so vehement that the old administration in the New York Joint Board was overthrown, and the outstanding figures of the rebels, the same men and women who had been excluded from the union by the old administration, were placed at its head.

The new union organization that emerged from the New York coup d’etat exhibited another precious side of the official American union system. There are some thirteen odd thousand furriers throughout the country; there are 12,000 of them in the city of New York. The New York furriers had put into office left wing class conscious leaders; the New York furriers voted for class conscious delegates to the International Furriers* Convention. Still, when that convention gathered in Boston in October, 1925, the one thousand odd members outside of New York were represented by a number of delegates far in excess of their numerical strength. A central group which hitherto marched in line with the New York left wingers was persuaded to move to the right, and the convention constructed one of the most bizarre pieces of union machinery: a reactionary national administration over a union in which at least 90 per cent of the membership are progressives.

All these antecedents are necessary to understand the strike that has just been concluded after seventeen weeks of unmatched struggle.

It was imperative for the union to check the encroachments of the bosses, to regain part of the territory relinquished by the old administration. That meant strike. The New York joint board was compelled to take a stand against the manufacturers’ associations not only for the purpose of improving the workers’ lives, but also to make it clear to the employers that a new force had come into being. Perhaps it was most important to convince the workers themselves, by deeds rather than by words, that things could be achieved through united conscious action to bring forth the fighting morale without which no working class organization can live and thrive either in times of actual struggle or in periods of truce. A strike became a prime necessity, an almost elemental demand, having its origin not only in reason but in the dark roots of the workers’ existence.

The struggle started some five months ago.

Behold the setting. An international office, located in Long Island City, not only hostile to the leaders of the New York fur workers, but actually afraid of being ousted from comfortable posts at the next national convention, and therefore determined to do everything possible to help the New York left wing (Communists they call them) to break their necks.

How these worthies scoffed at the attempt to organize a strike! Who shall lead it? Those “coffee-and-cake” boys? Those “Communist henchmen”? Those impractical untrained rebels of yesterday? How absurd! And who was going to back them up in this crazy undertaking? The Communists? But they are known as disrupters of the labor movement. Their task is to break the unions in order to please Zinoviev! Will they be able to lead a movement of 12,000 workers?

Of course not. Yet no chances must be taken. The national officers sent out emissaries to snoop among the workers, to spread among them the idea that the demands were excessive, to disrupt their unity, to break their morale. If these machinations have failed, if the fur workers have secured a substantial victory which enables them to begin a new era in their struggle, it is due to the entirely unexpected reserves of power, endurance, cohesion, sacrificing spirit that the strike revealed in the mass of the workers, and to the resourcefulness, flexibility, untiring energy and devotion of the left wing leaders, back of whom were the left wing of all the needle trade unions in New York.

Let us consider a few of the highlights of this spectacular struggle. There was the national officers’ attempt to hamper the struggle by attaching the strike fund and depriving the leaders of this most essential weapon; and accompanying this, the attempt to drive a wedge between the strike leaders and the mass of the workers, by carrying on thru the Jewish Daily Forward a campaign of denunciation repeatedly asserting that the strikers were dissatisfied with the “Communist” leadership.

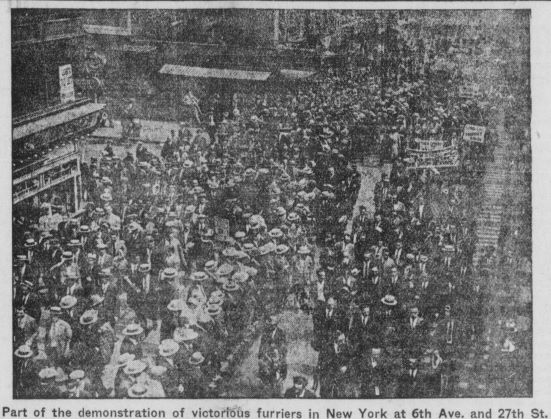

Then came the revelation of the plot of the national officers to settle the strike over the heads of the strikers’ representatives. They had been secretly meeting with the bosses, they had gained the official cooperation of the American Federation of Labor, and they had drawn up a set of terms on which they would end the strike. In short they had completed all arrangements to sell out the workers, and one fine morning the strikers were notified by a bulletin that they were to meet President Green of the A.F. of L. at Carnegie Hall to discuss settlement terms. A ballot was distributed among the strikers with a request to vote on the strike settlement proposed. It was a magnificent gesture. The existence of the General Strike Committee elected by the strikers was ignored. Of what importance was a Strike Committee? The strikers were to meet the big chief of the American labor movement and be instructed by him.

But the national officers failed to realize that it was a new fur workers union with which they were dealing. The officers were used to a body of members who did what they were told and asked no questions. But the striking fur workers of 1926 were of a different breed. They went to Carnegie Hall. They went with a very definite purpose in mind.

Perhaps President Green had a premonition. Or perhaps he waited developments behind the scenes. Anyway he did not appear on the platform to instruct the furriers. In his stead came Hugh Frayne, New York organizer of the A.F. of L., and by his side were the national officers of the fur workers’ union. Very evidently they had a program in mind; very evidently this meeting was a perfunctory step in a well-arranged plan. But there was a hitch. When the chairman rose to open the meeting, someone shouted “We want Gold.” This was most embarrassing. According to orders, Ben Gold, the strike leader, had been forcibly barred from the hall. The chairman tried to speak. “We want Gold!” “We want Gold!” The call was taken up all over the house. “We want Gold!” shouted the stormy human sea. “We want Gold!” echoed thru the hall and out into the street, to be caught up by the thousands outside.

Gold did not speak this time. But neither did anyone else. No terms of settlement were proposed, and nothing was voted upon. After two hours of this call for “Gold,” the officers gave up. The meeting was closed. The attempt to override their own strike committee was squashed by the workers themselves. Talk of the backwardness of the American working class…at least among the furriers in New York City!

There was a day when Mr. Frayne and also Mr. Green did address the fur strikers. But it was at a meeting arranged by the strikers’ own leaders and held in a great armory where the whole ten thousand strikers could be present. It was a meeting held after the abortive terms of settlement had been thrown in the discard; when the A.F. of L. had decided to cooperate with the strikers* own representatives; when Gold was present to be greeted with enthusiastic joy by the great mass of the strikers; and where a very nervous international president was allowed to speak only because Gold urged the workers to give him a hearing. No, the old line labor leaders did not fare well in this strike.

Neither could the police and the courts intimidate the strikers. Police activities in connection with this strike were intense and variegated far in excess of the practice prevailing even in our land of the free. There were nearly seven hundred arrests. Dozens of strikers were sentenced to months of imprisonment. Fines were numerous, and as to the number of skulls crushed and ribs bruised, there are no adequate statistics available.

In spite of this the union led the strike to a successful end. What made this strike a red chapter in the history of the American labor movement may be summed up as follows:

1 — Complete understanding and mutual confidence between the masses and the strike leaders. There was nothing the leaders concealed from the rank-and-file members of the union. There was no motion from the ranks that the leaders were loathe to consider. From the very start the members were made to understand that it was their own fight in which they had to rely on their own powers.

2 — The strike apparatus, consisting of the general strike committee, the shop chairmen meetings and the “halls.” The general strike committee was the executive organ — planning, supervising and executing the major steps of the strike. The shop chairmen meetings, a novel institution hitherto almost unknown in this union, was the legislative body deciding on the most important issues, every shop chairman being in close contact with the members of his shop. The “hall” was the meeting-ground of the strikers. Each shop and each cluster of shops housed in the same building were assigned a definite space in one of the halls. Each shop chairman had to keep tab on his own men. Should anyone be missing, the union would immediately send a watchman or a committee to trace his whereabouts so as to prevent him from scabbing. There was almost military discipline introduced in the union from top to bottom, yet it was a splendid manifestation of democratic centralism.

3 — A general picketing committee from among the most devoted union members. Wherever a check had to be put to strike-breaking activities, it was done by the members themselves and not by any professional outsiders.

4 — An ideological foundation. A campaign of enlightenment made it clear to the workers that it was more than a question of temporary gain, that their fight was part of the historic struggle of the working class against capitalist rule. The incidental and often trifling occurrences thus achieved a new significance. The whole struggle was put in historic perspective. Whoever still believes that only on the basis of very narrow and immediate practical demands can a union conduct a struggle, let him look at the fur workers’ strike.

5 — A left wing leadership consisting of men and women mostly young in years, people who had shared with the workers their daily hardships, most of them firm believers in the class struggle, some of them members of the Workers Party.

The strike has not reached all its objectives. Of the three major demands, the 40-hour week, equal division of work throughout the year, and a 25% increase in wages over the minimum scale that prevailed before the strike, the union won the 40-hour week and a 10% increase in the minimum wage scales, the 40-hour week plan having a proviso that during September, October, November and December work may be done on Saturdays for four hours at a special rate of payment to be agreed upon between the union and employers. Largely because of the strike-breaking activities of the international officers, it is not a complete victory, but it is, nevertheless, a substantial gain. The 40-hour week, i.e., five days* work and two days* rest, has been recognized in principle and made obligatory for at least eight months a year. In the remaining months, the workers may refuse to work without infringing upon the agreement. The significance of this strike, however, cannot be exhausted by the enumeration of purely material gains. Its importance reaches far beyond immediate achievement.

The strike has proven that a heterogeneous crowd of workers belonging to various nationalities and various age levels can be welded into a strong unified force capable of withstanding the most sinister attacks from within and without and capable of making inroads into the enemy’s camp.

The strike has proven that there is a fighting soul hidden in the working class, a readiness to stand firm in defense of proletarian class interests the like of which reactionary labor bureaucrats never dreamt of finding among the workers.

The strike was an illustration of the fundamental truth advanced by Communists for the last few years, that the many labor union office holders are enemies of the class struggle, who will resort to any tactics against the rebellious workers in order to maintain their positions.

The strike was an excellent manifestation of what can be done by a leadership that is in close contact with the masses of the union and at the same time guided by the ideology of the class struggle.

The strike has realized a new demand of the working class, an eight hour day and five-day week, a demand which marks a new step in the history of the labor movement.

Last, but not least, the strike has given the 12,000 fur workers of New York a new confidence in themselves, a new outlook, pride in their own achievement, disdain for their masters. It has given them that boldness, that lighthearted aggressiveness which makes new struggles and new victories a certainty.

This new spirit is perhaps the most precious item on the balance sheet of the strike.

In the full story of the labor movement, this red chapter may be only a small paragraph. Yet it is an heroic and colorful one.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

For PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1926/v01n04-aug-1926-New-Masses-2nd-rev.pdf