The full ext of one of the two final documents to be presented by the United Opposition, this signed by Bakayev, Kamenev, Rakovsky, Yevdokimov, Muralov, Smilga, Zinoviev, Peterson, and Trotzky and addressed to the 15th Congress of the Communist Party held in late 1927 that initiated the first Five Year Plan. In the aftermath of the United Oppositions’ public demonstrations on the tenth anniversary of Revolution in November, 1927, the Central Committee convened an extraordinary session to expel Trotsky and Zinoviev from the Politburo and the Party before December’s coming Congress. The Opposition, and this document, would have Kamanev and Rakovsky as its main, isolated, representatives at the Congress. The two main contentions, and they were intricately linked, were the pace and form of the new Five Year Plan, and relations with the peasants, in their many class differentiations, in an effort to bring Socialism to the countryside.

‘Counter-Theses of the Bolshevik-Leninist (Opposition) on Work in the Village’ from International Press Correspondence Vol. 7 No. 70. December 12, 1927.

1. “The dictatorship of the proletariat in the Soviet Union changes fundamentally the conditions and therewith the course of development of agriculture, for it creates a fundamentally different type of development of agricultural relations, a new type of class stratification in the village, and a new direction for the development of economic forms.” (Theses of the C.C. § 1.)

This assertion, in this absolute form, is wrong. The mere fact of the dictatorship of the proletariat does not yet transform capitalism into socialism. The dictatorship of the proletariat opens out a period of transition from capitalism to socialism. The best characterisation of this period is given by Lenin in his: “Taxation in kind”. The characterisation here made by Lenin of this transition period, with its internal class struggle, with its competition between capitalist and socialist elements, with its question of “Who whom?”, is replaced in the theses of the C.C. by a vulgar opportunist declaration confusing the NEP with socialism.

“So long as the private ownership of the means of production (for instance of agricultural implements and live stock, even when the private ownership of land has been abolished) and free trade continue to exist, so long does the economic foundation of capitalism also continue to exist.” (Lenin. Vol. XVII., p. 387.)

“Small production produces capitalism and the bourgeoisie, constantly, daily, hourly, in an elementary manner and on a mass scale.” (Lenin. 1926, Vol. XVII., p. 118.)

“In our programme every paragraph is something which every workman must know, understand, and digest. If he does not comprehend what capitalism is, if he does not understand that production is carried on by the small peasantry and home workers, constantly, unavoidably and inevitably produces this capitalism, if he does not grasp this, then he may declare himself a hundred times to be a communist, he may sparkle with the most radical communism, but this communism is not worth a farthing. We value only that communism that has an economic basis.” (Lenin. Vol. XVI., p. 134.)

One of two things must result: either the proletarian State will find itself able, thanks to a highly developed and electrified industry, to overcome the technical backwardness of the millions of small economic undertakings, organising these on the basis of wholesale production and collectivization, or capitalism, having recovered its strength in the village, will sap the foundations of socialism in the towns.

The difference between these two standpoints that of Lenin and that of the theses of the C.C. is self-evident. The Leninist question of: “Who whom?” no longer exists for the C.C. The theses of the C.C. gloss over realities, weaken the attention given by the proletariat to the incipience of capitalism, and thereby promote the growth of capitalist relations in the village. The Opposition considers this question to be the essential question of the whole period of transition.

2. The Opposition sees and appreciates the tremendous changes which have been brought about by the October Revolution. The dictatorship of the proletariat, the nationalisation of industry, of the transport service, of credit, the socialisation of trade, the monopoly of foreign trade, all this creates the possibility of successful progress towards socialism. And much success can already be recorded in the building up of socialism. But the Opposition is opposed to glossing over reality, or to the concealing the dangers, which are particularly great in our country.

The glossing over of the real state of affairs leads inevitably to opportunist errors. In the theses of the C.C. we read:

“The industry of the capitalist state of society depends during its development on conditions in the home market requiring as first premise the impoverishment of the main mass of the middle peasantry, the decline and proletarianisation of precisely the main group of the peasantry. As opposed to this, the process of the development of the home market under the dictatorship of the proletariat differs fundamentally from this process in the capitalist state of society. Here the growth of the market is not due to the proletarisation of the main mass of the peasantry, but to the increased prosperity of the middle and poor peasantry.” (Theses of the C.C. § 1.)

Further on the C.C. is obliged to admit that the “prosperity” of the kulak is increasing at the same time. The “prosperity” of the poor peasant increases, and with it the prosperity of the middle peasant and the kulak! This idyll has only one fault about it does not exist. In the village the class struggle is developing under the conditions given by the advancement of agriculture. At the same time the village is being proletarianised, the number of farms working without seed-corn is increasing. The C.C. fails to observe behind the enhanced productive forces of agriculture the growth and increasing acuteness of class antagonisms. Only under socialism, when there are no longer any classes, and agriculture is organised on the basis of socialised wholesale production, will it be possible to speak of a uniform growth in the prosperity of the whole mass of the population. That is how the question is defined in the Party programme written by Lenin, and that is how it is defined by the platform of the Bolsheviki-Leninists (Opposition).

3. The economic key position, in the first place big industry, form the decisive foundation for the whole development of national economy.” (Theses of the CC. § 2.)

This is correct. But the Party ought to know that this is the thesis of the Opposition, and that it was violently opposed at first by the C.C. Now the C.C. has appropriated this thesis. But the mere recognition of its correctness is not enough. If big industry is to form a decisive foundation in actual practice, a clear class policy is necessary, strengthening the economic and political positions of the proletariat. Without this, the thesis on the “decisive foundation, big industry” becomes an empty declamation. The question of the “decisive foundation” is the central question of the class struggle, in which the proletariat and the village poor join the middle peasantry against the kulak, against the NEP.-man, and against bureaucracy. The policy pursued by the C.C. subsequent to the XIV. Party Congress has not furthered the “decisive foundation” of industry. Their policy has been expressed both in the systematic failure of industry to keep pace with the general development of economy, and in the fact that the C.C. has not been able to decide upon an energetic class policy of redistribution of the national income (against the NEP.-man, kulak, bureaucrat) in favour of a more rapid industrialisation.

4. The theses of the C.C. deal quite inadequately with the main stages of our economic development after the introduction of the New Economic Policy. The growth of the capitalist elements in our economy is passed over. The tendentious elucidation of economic processes is an abomination to Leninism. (“Nauseus, tawdry, would-be communism.” Lenin.) The proletariat must not only realise its own achievements (which are indisputable), but at the same time the forces of its allies and its class enemies. Only then can it evolve and carry out a correct policy.

5. Seen from the Leninist standpoint, the peasantry is, the main mass of the peasantry not exploiting the labour of others that is that ally upon the correct relations with whom depends the security of the proletarian dictatorship, and with this the fate of the socialist revolution. Our tasks with relation to the peasantry during the present stage have been most accurately formulated by Lenin in the following words: “To be capable of coming to an understanding with the middle peasants without renouncing for one moment the fight against the kulaks, at the same time utilising to the utmost the help of the village poor.” (Vol. XV., p. 564.) This is exactly the standpoint of the Opposition in the question of relations between the working class and the peasantry.

6. In 1925 a new tendency appeared in the Party, a trend towards revisionism. First the existence of the kulak is denied altogether:

“The kulak is a bogy from the old world. He is certainly not a stratum of society, nor yet a group, not even a clique, in fact, he is only represented by a few individuals already in process of extinction.” (Boguschevsky: “Bolshevik.” No. 9/10.)

We are further lulled by a theory that the kulak is growing into Socialism most satisfactorily. “In any case the kulak and the, kulak organisation can find no other place, for the general lines of development in our country are laid down in advance by the proletarian dictatorship.” (N. Bukharin: “The Way to Socialism”, p. 49.)

“We lend him (the kulak) help, but he helps us too. In the end the grandson of the kulak will probably thank us for treating his grandfather as we have done.” (N. Bukharin: “Bolshevik”. No. 8. 1925.)

This “nauseas lying” (not would be communist lying, but bourgeois lying) about the kulak stands in flat contradiction to Lenin’s fundamental teachings, and as early as April 1925 Comrade N. Krupskaya was obliged to write as follows regarding Bukharin’s theory:

Comrade Bukharin is wrong on one other point. He says that he is not an advocate of class in the village. Advocate or not, the class struggle is none the less going on in the village, and is bound to go on.”

We find an accurate and emphatic rejection of Bukharin’s sugar coating of the kulak, capitalism and the class struggle under the dictatorship of the proletariat, in the following words of Lenin:

“The conquest of political power by the proletariat does not conclude its struggle against the bourgeoisie; on the contrary, it renders this struggle greater, acuter, more urgent and ruthless.” (Theses of the II. Congress of the Comintern on our main tasks. Collected works, Vol. 17, p. 234.)

In the resolution passed on the agrarian question by the Second Congress of the Communist International, Lenin wrote as follows:

“The big peasants are the capitalist enterprisers in agriculture, they work as a rule with some wage workers, and their only connection with the “peasantry” is their low cultural level, their way of living, and their personal physical labour. This is the most numerous of those bourgeois strata forming an immediate and decided enemy of the revolutionary proletariat. The work of the Communist Parties in the villages must be directed to the fight against this stratum, and towards the emancipation of the exploited majority of the working population of the villages from the ideological and political influence of these exploiters.”

“The kulak s”, wrote Lenin, “have more than once in the course of the history of other countries restored the power of the large landowners, of the Tsars, of the priests, and the capitalists. Thus it has been in all former European revolutions, in which the kulaks have been enabled by the weakness of the workers to return from the republic to monarchy, from power in the hands of the workers to the almightiness of the exploiters, of the rich idlers. The kulak may be easily reconciliated with the large landowners, with the tsar, or with the priests, even if they have quarelled, but NEVER with the working class.” “Fellow workers, let us go forward to the last and decisive struggle.” (Lenin Institute edition, pp. 1 and 2.).

Those who do not grasp this, but continue to believe that the kulak “will grow into socialism” are only fit for one thing to run the revolution onto a sandbank.

2. Hence in our national economy the card is staked on the so-called powerful peasant, that is, the essentially powerful peasant, the kulak.

“Our policy with regard to the village must advance along the line of removing and destroying the many restrictions hindering the growth of the undertakings of the well-to-do peasants and kulaks. We must say to the peasants, to all the peasants: Enrich yourselves, develop your undertakings, have no fear that you will be repressed.” Thus Comrade Bukharin at the XIV. Party Conference.

This slogan, derived from the French bourgeoisie, and alleged to have been abandoned by Bukharin, was repeated at the Siberian District Conference in 1927 by Syrzov, member of the C.C.: “make hay while the sun shines!”

This is a repetition of the slogan of the Ustryalov set, that is, of the slogans of that new bourgeoisie which dreams of leaning on the kulak and the NEP.-man, of deriving support from their economic growth, in order to exercise first an economic and then a political pressure upon the power in the hands of the workers.

Two years have passed, and now Comrade Bukharin declares, quite suddenly, as if nothing had happened, that it is now necessary to “take a line in the direction of exercising pressure on the kulaks, and on the bourgeois elements in general. This is the line to which we must now turn, and in this spirit we must carry on the preparatory work for the Party Congress. This same Comrade Bukharin now writes: “We must go over to a forced attack upon the capitalist elements, especially upon the kulaks.” (Comrade Bukharin’s report on: “The Tenth Anniversary of October.”)

This is an example of how certain politicians without principles vacillate!

But it shows at the same time that the Opposition has not fought in vain, that it has been right, if it has been the means of extracting such declarations as this from Bukharin even before the Party Congress.

Why is that which was declared at the XIV. Party Congress to be a “panic” about the kulak, and a “pillaging of the peasantry”, now designated on the eve of the XV. Party Congress as perfectly correct?

“At the XIV. Party Congress we executed a great manoeuvre” writes Bukharin. “We have freed the middle peasant from many fetters, and, by making concessions to the middle peasantry to a certain extent, we have created the possibility of the ‘fall of the kulak’.”

A manoeuvre has been executed! Lenin once wrote: “When a manouvre is executed after the manner of Bukharin, an excellent revolution can be ruined”. (Vol. XV. p. 45.) We are involuntarily reminded of these words of Lenin. Bukharin’s reference to a manoeuvre are an unsuccessful attempt to veil the fact that the policy of the C.C. since the XIV. Farty Congress has been un-Leninist with respect to the village, and that this policy has had to be considerably readjusted under the sharp criticism of the Opposition. This abrupt change of front (though so far in words only) on the part of the C.C. in the direction of fighting the kulaks compels the present Party leaders to face two alternatives: Either Bukharin’s theory of the peaceful absorption of the kulak into Socialism remains in force, in which case there appears to be no valid reason for declaring war on the kulak. Or this whole “theory” collapses in face of the mere fact of the proclamation of the new course. This would, however, have to be admitted straightforwardly.

8. The kowtowing before the kulak has inevitably entailed the setting aside of the agricultural labourer and the village poor from their place as social basis of the dictatorship of the proletariat in the village.

“Do you not even know that among the village poor there is a certain proportion of people who do not want to do anything at all, who may simply be designated as work-shys? It is these shirkers who cry loudest that we are pursuing a kulak policy”. This was said at the XIV. Party Congress by one of the secretaries of the C.C., Comrade Kossior. (Stenographic minutes, p. 313.)

“This sacred truth” declares the bourgeois Professor Ustryalov in praise of Kossior, “proclaimed by the mouth of a practical provincial functionary, is certainly not gratifying to the dignitaries of the Opposition.” (Article by Prof. Ustryalov: “The XIV. Party Congress”.)

“The poor in the rural districts where natural economy obtains consist of unhappy producing invalids”, declares Comrade Kalinin. (“On the Village”. Edition 1925, p. 61.)

“Just as our present village hates the kulak, so it despises the shirkers. Industrious and energetic workers can indeed have no other feeling towards a farmer’, who, for instance, when field work is in full swing, instead of working like the others, ‘sits fishing by the stream’ or ‘goes seeking mushrooms in the forest”… Such ‘village poor’ as these can naturally expect no support from the Soviet power” writes the People’s Commissary for Agriculture, Comrade A.P. Smirnov. (“The policy of the Soviet power in the village”. State publishing office. 1925. p. 42.)

To say that the main support of the proletariat in the village at the present time is the village poor is therefore equivalent to repeating by rote what we have learnt, as a dull scholar clings to the formulas he has heard somewhere. Of course it is true that the main support of communism in the village is the village poor. But is it therefore right to assert that the main support of the Soviet power can be nothing else than the village poor, or that the Soviet power, supported by the village poor alone, can retain power?… In times of peace, when no one wages War or makes attacks upon us, we can maintain our power, but in these circumstances we could maintain it without the village poor…Let us take for instance the recruiting for the peasants’ army: It is among the village poor that we find the greatest number of illiterates, the greatest number of the unfit, but into the army there go the strongest, the best developed… And finally, who plays the leading role in the army? The physically strong, the most highly developed… And do you want us to be dependent solely on the village poor when faced by war, at a moment when the State is in the greatest danger?”, (Kalinin’s speech at the Party Conference at Tver, in the spring of 1927.)

“The village poor is still permeated with the passive methods of thought. It sets its hopes on the G.P.U., on the authorities, on everything imaginable, except on its own powers. This inertia and passive manner of thought must be removed from the mentality of the village poor.” (Stalin, speech at the XIV. Party Congress.)

The declarations quoted above of the most prominent leaders of the C.C. are as far removed from what Lenin said about the village poor as Marxism is removed from the ideology of the S.R. This is no proletarian estimate of the village poor, but a kulakian estimate, an estimate from the standpoint of the landowning farmer.

It is only the kulak, the farmer, the petty bourgeois, who can look on at the process of proletarianisation among the village poor, inevitably accompanied by a weakening of its economic status, and declare the village poor to be “shirkers”, “passive”, and the like.

9. The abandonment of the position taken by Marxism and the adoption of the theories of the social revolutionaries is again apparent in the question of the petty bourgeois character of peasant property and of peasant economy.

Comrade Stalin, speaking on the capitalist development of agriculture in the West, writes as follows:

“Not so in Russia. Here agriculture cannot develop on these lines, if only for the reason that the existence of the Soviet power, and the nationalisation of the chief instruments and means of production, do not permit such a development.” (Stalin: “The Principles of Leninism”.)

“The peasantry is not socialistic by reason of its position. It must, however, tread the path of socialist development, and it will certainly tread this path, for there is no other way to save the peasantry from want and misery, and there can be no other way.” (Stalin: “On the questions of Leninism”, p. 56.) 2

Anyone who simply states this, without referring with a single word to the class struggle in the village, or on the necessity of an energetic fight against the kulak, merely repeats the old nonsense of the opportunists, the petty bourgeoisie, and the Social Revolutionaries. And this is what the Party is giving out as Leninism! In actual fact it is a policy cloaking kulakism, a policy of concealing the kulak efforts to drive the village on to the path of capitalism. The capitalist elements of our economy are glossed over, covered up. It is not for nothing that the periodical “Rul”, after reading Bukharin’s and Stalin’s speeches on the kulaks, wrote as follows:

“The Social Revolutionaries have now actually the right to fold their arms: Time and the Soviet power itself are working for them.” (Leading article. 16th October, 1927.)

10. Revisionism abandons one of the main theses of Marxism, according to which only a powerful socialist industry can help the peasantry to reorganise agriculture on the basis of collectivism. Attempts are being made to oppose Lenin’s cooperative plan to Lenin’s electrification plan. As a matter of fact the electrification plan does not do away with or replace the co-operative plan, but supplements it.

Bukharin, however, writes as follows:

“When we went over to the New Economic Policy, Comrade Lenin had one strategic plan for the solution of this problem, but when he wrote his article on the cooperatives, that is, when he bequeathed us his last legacy on the principles of economic policy, he had another strategic plan.” (Bolshevik”, No. 8, 1925.)

This invention of Bukharin on the alleged two plans of Lenin is supported in the theses of the C.C. (§ 11.).

This misrepresentation of Lenin’s idea is in full accordance with the course taken towards the “powerful middle peasant”, with the outcry on “over industrialisation” on the part of the Opposition, and represents a direct concession to the petty bourgeois pressure on the Party. To oppose the “cooperative plan” to the electrification plan implies at the same time a denial of the “leading role” of big industry in economy and in the building up of Socialism.

“The actual and sole basis for consolidating the means for building up the socialist state of society is big industry alone, nothing else. Without the great factory, without highly developed large industries, there can be no thought of Socialism. We in Russia know this much more definitely than before, and we no longer speak in vague or abstract terms of the reconstruction of big industry; we speak of a definite and exactly calculated plan of electrification.” (Lenin. Vol. XVIII. part I. p. 260.)

Forced by the criticism of the Opposition to beat a retreat, the C.C. seeks to take cheap revenge by means of an attack on the Opposition:

“It should be mentioned that a characteristic feature of the Opposition is its lack of faith in the possibility of guiding the main mass of the peasantry on to the paths of socialist construction through the agency of the cooperatives. This signifies a renouncement of Lenin’s cooperative plan, and at the same time the abandonment of this Leninist position by the Opposition. This departure from Leninism is the inevitable result of the entire liquidatory attitude of the Opposition, which denies the possibility of building up socialism in our country:”

A glance at the platform of the Bolsheviki-Leninists suffices to show the absurdity of this assertion. It is as hopeless a slander as the endeavour here made to put into Lenin’s mouth a typically S.R. conception of a united mass of peasantry, growing into Socialism without inner class conflicts. Here again we see the attempt to cloak the role of the kulak, to ignore the kulak’s efforts to subordinate the co-operatives to himself, and to make them into instruments for his own enrichment. The liquidators of Leninism, both in theory and practice, are those who have carried on in the course of the two years since the XIV. Party Congress a policy actually covering the kulak, and waging bitter war on all who have drawn attention to the growth of the kulak, his accumulation, and his influence.

11. Relying on these revisionist tendencies in the official course, the representatives of the new bourgeoisie, who are interwoven with some of the threads of our state apparatus, are openly seeking to divert the policy with regard to the village into capitalist channels. In this way kulakism and its ideologists conceal all their claims and demands behind a concern for the development of the productive forces, for the expansion of the traffic in commodities “in general” and the like. But in actual fact the kulakian development of productive forces and the development of the goods traffic conducted by the kulak undertakings, retard the development of the productive forces of the whole of the remaining mass of the peasantry.

The Central Committee must refute these accusations or condemn the revisionists. These accusations are based on facts and documents. They are incontestable. There remains only the second alternative.

12. In the question of the differentiation of the peasantry, the theses of the C.C. assume:

“That our type of development, as opposed to the capitalist type, which is expressed by a weakening (‘washing away’) of the middle peasantry, by which the extreme groups of the poor and rich peasantry increase, shows our type of development to consist of a process strengthening the middle peasant group, accompanied at the present time by a certain growth of the kulak group at the expense of the more prosperous section of the middle peasantry; one part of the poor peasantry is proletarianised, whilst the other and larger part rises gradually into the group of the middle peasantry.”

“One of the most glaring errors of the Opposition is its mechanical transference of the laws ruling the development of peasant economics under capitalism, in their full extent, to the epoch of the dictatorship of the proletariat, thus following in the train to the bourgeois ideologists.”

In order to settle the question of who is really “following in the train of the bourgeois ideologists”, we quote a characterisation of the process of differentiation given by the Right social revolutionary Organovsky in one of his works:

“An analysis of the actual data from the beginning of the period of restoration up to 1926 shows that the process of differentiation, in the village has not been two-sided, but a one sided process of a ‘general upward movement’, in which the higher groups grow more rapidly than the others, but the middle peasantry grow at the same time, and the lowest groups decline.”

Here we see the theses of the CC. helplessly repeating the old bourgeois theories of the process of development in agriculture, theories which have invariably been defended by bourgeois national economists against the Marxists at all times, up to the war, up to the revolution, up to the Soviet power. The “Leninist” Molotov and the Right Social Revolutionary Organovsky (an irreconcilable opponent of Lenin), have found a basis of mutual agreement in their estimate of the chief question of the development of our village. Both deny: 1. the existence of a capitalist differentiation in the village; 2. the fact of the “washing away” of the middle peasantry; both underestimate the growth of the kulak; both shut their eyes to the proletarianisation of the village. This agreement is not accidental, for the principles held by the C.C. in the peasant question coincide fundamentally with the Social Revolutionary theories, that is, with the main theories of the bourgeoisie. The Party must call itself fully to account with respect to the dangers incurred by this change of ground, brought about by the pressure of petty bourgeois encirclement.

The actual facts, however, completely refute both the bourgeois ideologists and those communists who echo them through the mouth of Organovsky. During the last few years differentiation has advanced rapidly in the village, and has created the elements of capitalist development. The official statistical data on the differentiation of the village, despite their incompleteness and one-sidedness, still give a graphic idea of its speed and character.

13. In 1917 and 1918 the October Revolution was accompanied in the village by a levelling up process among the peasantry. Lenin drew attention to this when speaking of a merging of the different strata of the peasantry in the middle peasant class. The farms with large areas under cultivation and with large quantities of live stock had become considerably smaller, whilst the number of peasant-households without cultivated land and cattle diminished.

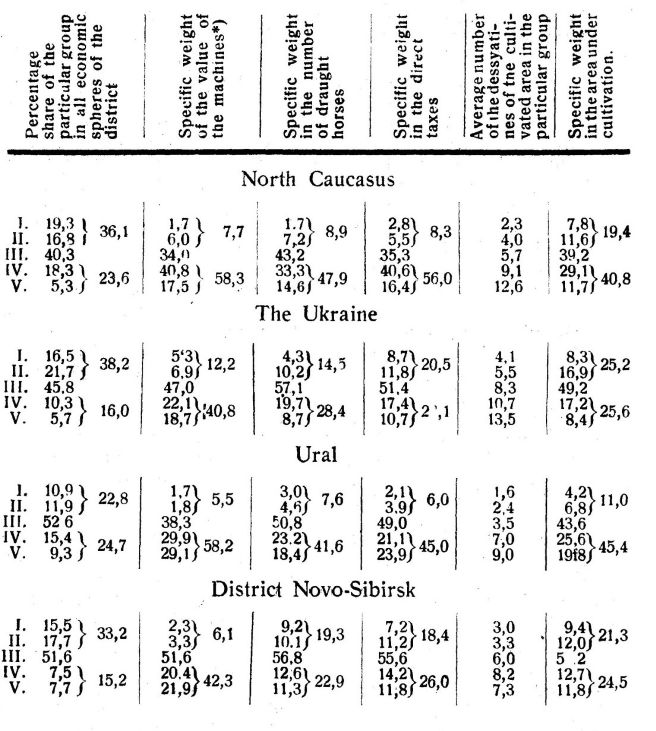

This process of equalisation continued until about 1922. Under the New Economic Policy the process of differentiation set in again. The appended data were compiled by the Communist Academy and the Central Control Commission from the state finance accounts for 1924/25. They show clearly the classification of the peasant farms in social groups. These data refer to those agricultural districts in social groups. These data refer to those agricultural districts playing a decisive role both in providing the towns with grain and furnishing supplies for export.

The whole of the peasant households are divided into five groups: I. the proletarian; II. the semi-proletarian, III. the middle peasant, IV. those resembling the capitalist type, and V. the small capitalist. The method of classification here employed with reference to the social groups of peasantry prevents an exact ascertainment of the extent and influence of the well-to-do undertakings. Any improvement of the method would not, however, alter the main conclusions to be drawn, since a considerable part of the peasant households under group IV. “merge into” group V., the capitalist.

These figures must be accorded careful attention. Firstly, because they represent the first serious attempt at classifying the peasant undertakings in social groups, and secondly, because they have been compiled by authoritative institutions which. cannot be suspected of any tendency to exaggerate the differentiation.

The proletarian and semi-proletarian undertakings combined by us in one single group, form approximately 25 to 40% of all undertakings in the districts dealt with. The middle peasant group forms 40 to 50%, that is, one half; in two districts (Caucasus and the Ukraine) less than one half. Finally, the well-to-do group, consisting of the small capitalist and capitalist type of undertaking, forms 15 to 25 per cent. of all undertakings.

The State Planning Commission, when issuing and commenting on this table (in “Control figures for 1927/28”, pp. 353 to 355), observes:

“The top capitalist stratum controls a considerable portion of the total wealth of the village.”

This admission is very important. It refutes the fable that the Opposition over-estimates the kulak. When the State Planning Commission, forced to confirm what the Opposition has been maintaining for two years, seeks consolation in the idea that “the main mass of wealth is, however, not in their (the capitalist top stratum) hands”, then this is surely a very poor consolation. If not merely a considerable portion, but the whole of the wealth of the village were in the hands of the capitalist stratum, this would mean the triumph of capitalism in the village. It is not very wise to find consolation in the fact that this is not yet the case.

It is necessary 1. to recognise the correctness of the oppositional estimate of the influence of the kulak; 2. to inform the Party and the working masses on this point; 3, to draw the obvious practical and political conclusions, and not seek consolation in the idea that capitalism, whilst already controlling a considerable portion of the wealth of the village, has not yet seized upon the whole.

The economic and political specific weight of this or that group of peasant undertakings is determined not only by its specific weight in the economy itself, but by its specific weight in the control of the most important means of production.

Of the means of production, machinery is most unequally distributed. The poor peasant farms possess only a very small proportion of the total value of the machines in use; in the Ukraine 12%. The well-to-do peasant class possesses 40 to 60% of the total machinery. One half, or more than one half of the machinery in use in the above districts is concentrated in their hands.

The distribution of draft cattle is approximately the same as that of machinery, although here the specific weight of the poor peasant farms is somewhat greater in some districts than in the distribution of machines. It must be observed that the figures regarding draft cattle refer to the number and not the value, which is by no means the same thing. The well-to-do farmer invariably possesses more valuable animals. If we calculate the distribution of draft cattle by its value and utility instead of by number, we find the specific weight of the richer peasant increasing, that of the poorer peasant declining. The areas under cultivation are distributed in a somewhat similar manner, with a slight difference. 10 to 25 per cent. of the area cultivated belongs to the poor peasant group, almost one half belongs to the middle peasant in every district, and 25 to 45 per cent. to the rich peasant. The share of the poor group in the area cultivated is somewhat larger than its share of machines and horses. This is to be explained by the fact that a considerable part of the poorer undertakings, not possessing their own means of production, are obliged to till their ground with hired draught animals and machines, and to hire these from the kulaks on enslaving terms. In many cases, again the land belongs only nominally to the poor peasant, and is left nominally in his possession to avoid the payment of taxes, whilst in reality it is in the hands of the well-to-do peasant who has leased it. Statistic cannot control this state of affairs.

The main conclusion to be drawn from these figures is that the great mass of the most important means of production belongs to the well-to-do strata of the village. These means of production, in the hands of the well-to-do peasant, are a tool for the exploitation of the poor.

14. The graphic presentation of the direct taxes is of great interest. Direct taxation is one of the most effectual instruments for the regulation of social processes in the village. It must be used, above all, for restricting the exploiting tendencies of the topmost capitalist stratum of the peasantry. But when we compare the specific weight of the three groups in control of the means of production, and in the payment of taxes, we find that the poor peasant groups pay relatively no less, if not actually more, in direct taxes than the rich and middle peasantry.

The burden of taxation is imposed directly on the means of production, proportionately, without any progressive scale for the richer groups. The assessment imposed in 1925, and since then, slightly raise the rate of taxation for the richer groups, but since then the process of differentiation has made rapid strides.

Indirect taxation has swelled to a considerable extent, increasing the relative burden of taxation on the poorest strata of the peasantry.

15. Exhaustive data on the course of the differentiation during the last two years and a half are not available. The above classification into groups is based on the statistical data of the economic year 1924/25. The only data at our disposal are those on the changing distribution of the area under cultivation in 1925 and 1926. The cultivated area groups do not coincide exactly with the social groups, but there is nevertheless an undoubted connection between the social groups and the extent of the cultivated area controlled by them.

The changes taking place in the cultivated area groups up to 1925 were characterised by the lessening of those groups of peasant undertakings possessing no or little cultivated land, and by the growth of farms with large cultivated areas, The growth of the groups with large cultivated areas has been much more rapid than the decline of those with little or no cultivated land. The groups with little or no cultivated land have diminished by 35 to 45 per cent. during the last four years; the group of those possessing 6 to 10 dessyatines has increased by 100 to 120 per cent in the same time. The group possessing 10 and more dessyatines has increased by 150 to 200 per cent.

The decline of the percentage of the groups with little or no cultivated land is caused to a great extent by liquidation and devastation. Thus in Siberia in one single year 15.8 per cent of the farms without cultivated land, and 3.8 per cent of the farms with cultivated land up to 2 dessyatines were liquidated, and in North Caucasus 14.1 per cent of the farms without cultivated land and 3.8 per cent of those with land up to 2 dessyatines.

In 1925 a growth of the group without cultivated land could be recorded for the first time. The specific weight of the groups without cultivated land was shown by the spring enquiries of 1924 and 1925 to have increased from 2.1% to 2.8% in the areas not producing sufficient grain for their own needs, and in the areas producing a surplus from 4.8% to 5.1%. 1926 shows a growth of the groups without cultivated land all over the R.S.F.S.R.

We see from these figures that the specific weight of the outer groups grows at the cost of the middle groups.

That a certain degree of progress may be recorded for the groups with small areas of cultivated land does not prove their increasing economic independence. The data given above on the distribution of the means of production shows the specific weight of these groups to be exceedingly small. These groups possess the fewest horses the fewest agricultural implements. The overwhelming majority of these farms work their land with the aid of hired cattle and machines. This is the group which Lenin named agricultural labourers with a holding of land.

16. Land is being leased to an increasing extent from year to year. The statements referring to the areas producing a surplus of grain, from 1925 to 1926, show a general increase of tenant farms from 11.2% to 18.2%, the distribution among the cultivated land groups being as follows:

With cultivated areas up to 2 Dess. With cultivated areas from 2-6 Dess. 54.9 54.3 With cultivated areas of 6 and more Dessy 14.0 16.1 69.6 75.2 10.3 12.8 (“Statistic Bulletin of the Central Statistic Administration” 1927.) The rapid extension of tenant farming up to 1926 may be explained by the fact that the effect of the Third Soviet Congress, at which capitalist leases were legalised, made itself felt. Even in 1924/25, when leasing was semi-legal, the data, based on all too moderate estimate, show the area leased to have been 7.7 million dessyatines. To judge by the role at which land leases are increasing, the total area leased in 1927 must be approximately 15 million dessyatines.

The above facts indicate a rapid process of concentration in land leasing, for they show that more than three-quarters of the total area leased is concentrated in the hands of 10 per cent of the agricultural undertakings belonging to the highest group. 16 per cent of all farms, possessing 75.2 per cent of the land leased, lease to others only 12.8 per cent, whilst the groups possessing small cultivated areas up to 2 dessyatines sublease 44.4 per cent and lease for their own use only 3.4 per cent. The middle group, with 2 to 6 dessyatines, lets out on lease 42.8 per cent, and hires only 21.4 per cent.

These facts prove in an indisputable manner the direction of the capitalist process of differentiation, but not in the least a general growth of all groups of the peasantry. On the one hand we observe a process of concentration in the cultivation of land, and on the other an increase of economic dependence on the part of the lowest economic groups on the highest economic groups.

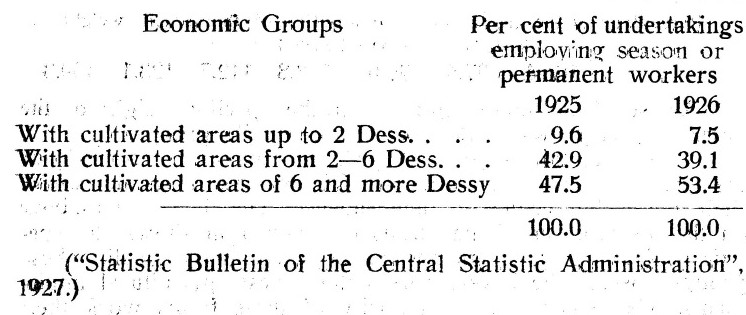

17. The concentration of land utilisation and of the means of production in the hands of the highest group is accompanied by the increased employment of wage labour. Again, both the lowest and the middle groups of the peasantry throw off an ever increasing number of superfluous workers, a result of either the complete liquidation and devastation of their undertakings, or of the lack of employment at home for various members of the families. This “surplus” labour supplies hands for the kulak or “powerful” middle peasant, drifts into the towns, or joins the army of the unemployed. This is not to be explained solely by the fact of agrarian over-population. It is closely bound up with the differentiation of the village.

The data on the employment of wage labour are unfortunately less accurate than those on land leasing. It has, however, been possible for statistics to follow the general tendency. The number of farms employing seasonal labour in the areas producing a surplus of grain has increased from 1.5% to 2.9%, and the number of farms employing day labourers from 2.8% to 8.4%. The distribution of wage labour, like that of leased land, is extremely unequal.

18. The inequality in the distribution of cultivated land and of the means of production is further confirmed by the inequality in the distribution of cultivated land and of grain reserves among the various groups of peasant farms. On 1st April, 1926, 58% of the total grain reserves of the village were in the hands of one-sixth of the farms. (“Statistic Review”. No. 4. p. 15, 1927.)

The grain reserves on hand at the close of the supply year 1926/27 amounted to 800 to 900 million poods, reaching however one milliard poods by the end of the grain purchasing season of the current year. These reserves are much greater than those of pre-war years, and considerably larger than the necessary reserves against emergency. These reserves, in the hands of the well-to-do strata of the peasantry, are an instrument for the exploitation of the poor peasants, a means of frustrating our economic plans. In the hands of the kulak they are an effective weapon against the socialist elements of the economy of the Soviet Union.

This fact, which can now no longer be disputed by anyone, is a complete confirmation of the warnings uttered by the Opposition even before the XIV. Party Congress, and a complete confirmation, of the prospect to which the Opposition already at that time called the attention of the Farty. And when now the slogan of a “forced”, that is, an increased and accelerated “attack on the kulaks” is suddenly proclaimed (see “Prayda”), then this is nothing more nor less than an admission that the attack on the kulak is belated, and that the kulak has had leisure to strengthen his position during the time the leaders of the Party have been conducting a fierce fight against those who had warned of the increasing power of the kulak.

In actual fact, the slogan of “fire against the Left”, the fight against the Opposition, and the accusation that the Opposition “forgets the middle peasant”, have all been a screen behind which the process of the rise of the kulak, and the rise of his complement in the city, the NEP.-man, has been able to proceed at a rapid rate. This is the objective result of the course pursued by the C.C. during the last two years.

19. The splitting up process going on among peasant farms does not weaken the course of differentiation, but strengthens it.

Machinery and credit, instead of serving to socialise agriculture, are falling completely into the hands of the kulaks and well-to-do peasants, and further the exploitation of the agricultural labourer, the poor peasantry, and the economically weak middle peasant.

Along with this form of exploitation usury is also increasing. An investigation of about one thousand cotton plantations in Central Asia showed that nearly 70 per cent of these undertakings are obliged to resort to the usurer. The extent of indebtedness to the usurer per dessjatine of area cultivated is greatest among the poor peasants. The extortionate character of the usury system is shown by a comparison of the amount of agricultural tax paid with the amount of abnormally high interest paid to the usurers. The poor peasantry paid in 1926 four times more to the usurers than their amount of agricultural tax, the middle peasants one and a half times as much, and the well-to-do peasantry one third.

20. The revolution brought about a great equalisation in the distribution of land. But it brought no equalisation in the distribution of the means of production. But Lenin wrote:

“It is clear that no equalisation of the ownership of land can remove the inequality of the actual utilisation of the land, so long as there exist differences among the property owned by the farmers, and a system of barter which aggravates these differences.” Vol. IX. p. 676.)

It suffices to compare these words of Lenin with the theses of the C.C. to see how far the present majority of the C.C. is removed from Marxism and Leninism.

Despite the great advance made by all these processes leading to the diminution of the specific economic weight of the middle peasant, the middle peasant still remains the numerically strongest group in the village. The attraction of the middle peasant on to the side of socialist policy in agriculture is one of the most important tasks of the dictatorship of the proletariat. But the staking of our cards on the so-called “powerful peasant” is tantamount to staking them on the further decline of the middle peasant strata, and on the undermining of the nationalisation of the land.

4. Nationalisation of the Land.

21. The land leasing system developing in the village; the present position of soil utilisation, in which the guidance and control of the Soviets is accompanied by a control of the land by land societies falling more and more under the influence of the kulak; the decision of the IV. Soviet Congress on money payments for the transference of land all this is undermining the foundations of the nationalisation of the land.

The extent of the land leased is already about 15 million dessyatines. Thee quarters of this immense area are being cultivated by well-to-do farmers. In view of this fundamental fact, the measures proposed by the theses of the C.C. for the firmer establishment of nationalisation are extremely inadequate, and are indeed in many cases calculated to deprive the village poor of land to an even greater extent. And on the other hand the limitations of the periods for which land may be leased, as proposed by the theses of the C.C., though in themselves correct, do not in the least solve the problem of the distortion of the nationalisation principle by the development of the leasing system.

22. The maintenance and firmer establishment of the nationalisation of the land are our most important tasks, for the nationalisation of the land, in the hands of the Soviet power, can and must be one of the most effective means of accomplishing the socialist transformation of the village, and of combating the above-named process of capitalist degeneration. The Party must already now draw up a comprehensive state plan containing measures for utilising the nationalisation of the land for the purpose of the socialist transformation of the village, and must submit this plan to the judgment of the Party and Soviet organs. The final settlement of the relations between the Soviet State the controller and administrator of the nationalised land and those who cultivate this land, will require a number of years, but the general direction of the work must be decided upon at once. The masses of the peasantry the agricultural labourers, the poor peasants, the middle peasants, must be given the possibility of participating in the preparation and discussion of these measures.

23. The totality of these measures must ensure:

1. The retention of land for the peasant strata with few possessions. The State must take up the organisation of comprehensive aid for these strata, enabling them to cultivate the land on a collective basis.

The restriction of the endeavours to exploit on the part of the kulak farms and of those farms tending to become kulak farms.

3. The raising of the technical basis of agricultural production and a comprehensive development of the social and co-operative forms of economic undertakings, accelerating the transition to the collective form.

The right of the Soviet power to control the land owned by the country must be realised, in order to secure the carrying out of our land policy, and to defeat the increasing efforts of the kulak to obtain control of the land of the country (by means of leases, etc.);

The existing land societies must be gradually transformed into land co-operatives, these cultivating the nationalised land collectively, and making it their task to carry out collectively a number of economic measures.

One of the most essential measures for the consolidating nationalisation must be the subordination of the land society to the organs of the local authorities, and the establishment of a sharp control over the distribution and utilisation of the land, this control to be exercised by the local Soviet, purged of kulak influence, and to protect the interests of the poor and middle peasantry against the violent attacks of the kulaks. The part played by the local organs of the Soviet power in the organisation of the whole economic life of the village must be greatly extended, especially with regard to the carrying out of the system of agrarian technical measures. The local Soviets must be the initiators of the organisation of peasant farmers, and the executive organs of social policy in the villages.

The realisation of this policy means that in the village the Soviet power must look for the all-round support of those strata of the rural population and of those economic forms which support the proletariat in the socialist reorganisation of agriculture. This system will give the Soviet power an effective and immediate weapon in the struggle against the capitalist elements and processes in the village.

The carrying out of the above programme for the security of the nationalisation of the land demands an exact ascertainment of the extent, quality, and estimated value of the land. For this purpose the regulation of the land must be accelerated and a land register organised (quality and estimated value of land).

The work of regulating the land must be carried out entirely by the State, the utmost importance being attached to the regulation of the land of the collective undertakings and the poor peasantry and their interests being safeguarded. In this connection it will be necessary to proceed to the abolition of the agricultural tax, for tax hits external features of agricultural undertakings without consideration of their actual proceeds, and therefore falls most heavy upon the economically weak, evoking a justifiable dissatisfaction. This tax must be replaced by taxation in accordance with the quality of the soil and the distance from the market (taxation of proceeds), and all poor and economically weak undertakings [missing words] layer of kulaks is to be subjected to a progressive income tax.

The Party must energetically resist every attempt to destroy or undermine the nationalisation of the land, this main pillar of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

5. The Co-operatives.

24. The task of socialist construction in the village is the reorganisation of agriculture on a basis of big collective undertakings using machinery. For the main mass of the peasantry the most direct path to this goal is the coperative, as shown by Lenin in “The Co-operative”. Here the dictatorship of the proletariat and the whole Soviet structure can smooth the way for the peasantry. The growing industrialisation of agriculture is the sole basis possible for the extension of the foundations of the productive socialist co-operatives (collectivisation). Without a technical revolution in the methods of production them selves, that is, without machinery in agriculture, without the scientific rotation of crops, without fertilisers, and so forth, there is no possibility of comprehensive and successful work towards the collectivisation of agriculture.

25. The productive and selling co-operatives can prove a path to Socialism only if: 1. they are under the immediate economic and political influence of the socialist elements of our economy, above all of big industry and the trade unions; 2. the process of transition to co-operation in the trade with agricultural products is made to lead gradually to co-operation in production itself, and to its increased collectivisation.

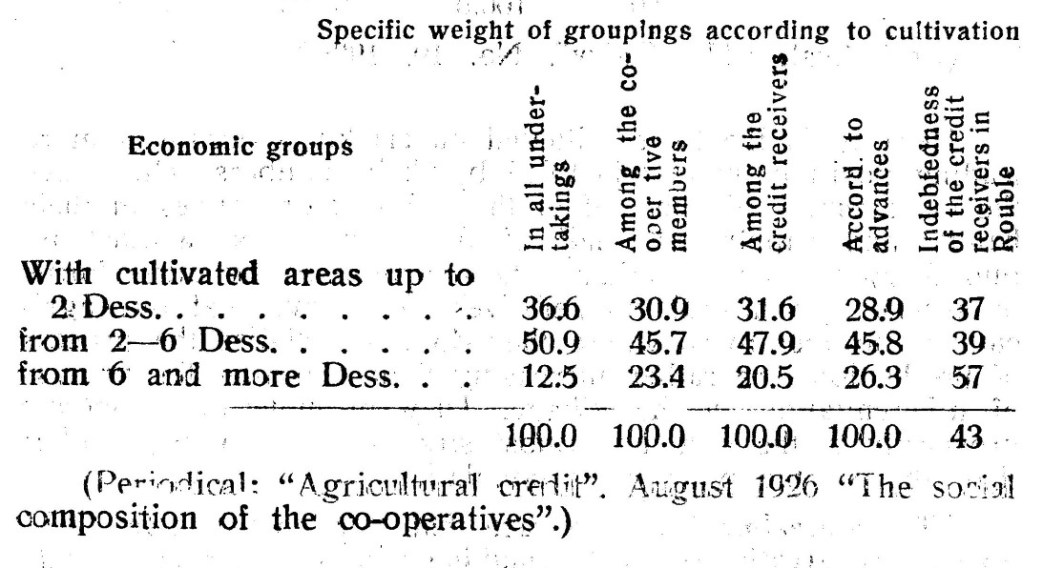

The class character of the agricultural co-operatives is not determined by the comparative numbers of the different groups of peasants organised in the co-operatives, but mainly by their economic specific weight.

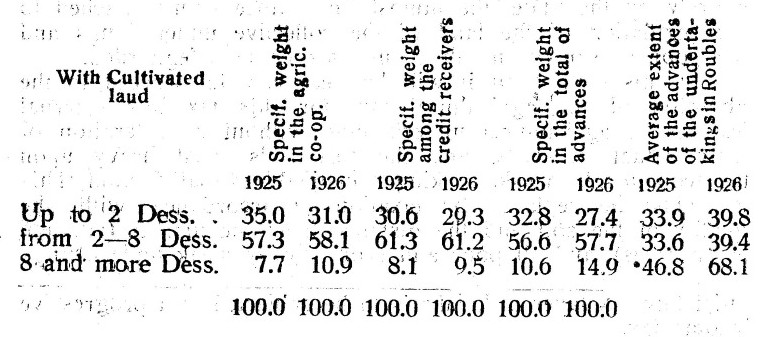

The data available at the present time on the spread of co-operation among the various social strata of the village show, however, a comparatively large participation of the well-to-do strata of the village in the whole work of the co-operatives. Thus the statements issued on the agricultural credit co-operatives of the R.S.F.S.R., which comprise two thirds of the members of all agricultural co-operatives, give, the following picture:

This table shows that the well-to-do peasants participate in the co-operatives to a greater extent than the poor and middle peasants, and receive comparatively more credit.

A comparison of the data of 1925 and 1926 shows an increased participation on the part of the well-to-do peasants, both with respect to numbers, and to the extent of the credits granted them.

The inclusion of farms of two to eight dessyatines in the middle group is tendentious, for it lowers the comparative weight of the well-to-do group. This table nevertheless again shows the growth of the kulak in the co-operatives. As matters stand, the richer a peasant is, the greater the means he receives from the present agricultural cooperatives, whose funds are supported to a great extent at the expense of the Soviet State.

We see therefore that the credit granted to agriculture, which could and should lend substantial assistance to the poor peasant, is in actual fact put at the disposal of the rich.

Agricultural credit grants must cease to be a privilege of the economically powerful and rich elements of the village. Under present conditions the funds of the village poor, small as they are, are not infrequently diverted from their original purpose to serve the interests of the rich and middle peasantry; this state of things must cease.

26. Not only must the grants to the poor peasants’ funds be considerably increased, but the whole system of agricultural credit must be altered in favour of cheap long-term credits to the poor and small owning middle peasantry. The present system of guarantees and securities must also be altered. The increased specific weight of the rich peasantry in the co-operatives is especially noticeable in the special agricultural co-operatives. The data for the dairy co-operatives, comprising the whole of the dairy districts in the R.S.F.S. R., are as follows:

Here again the better situated undertakings occupy a more leading position than is justified by their numbers. They have the management of one half of the dairy co-operatives in their hands, and supply one half of the milk to be worked up into dairy products. Similar data are supplied by other forms of special agricultural. cooperatives. All prove that our agricultural co-operatives, where they do not socialise the process of production, are rather increasing than lessening the process of differentiation in the village. They promote the economic prosperity of the rich, uppermost stratum of the village rather than that of the poor rural population.

The concealment of the fact that our co-operatives have up to now greatly tended to combine and serve the rich strata of the village is diametrically opposed to Lenin’s views. If the co-operatives are to fulfil the great socialist task set them by Lenin, the first necessity is the exposure of the defects of the present co-operatives, and there must be no misuse of Lenin’s words on the “Real co-operation of the real masses of the population” for the purpose of cloaking the fact that the kulaks and the rich peasantry have hitherto exploited the co-operatives for their own organisation and accumulation.

It is the task of the Party to make of the agricultural cooperatives a real means for bringing together the poor and middle peasantry, enabling these to take up a successful struggle against the growing economic power of the kulak. It is necessary to induce the agricultural workers, systematically and energetically, to take part in the co-operative organisation of the village.

6. Soviet Undertakings and Collective Undertakings.

27. The rise of the individual farmer must be opposed by an even more rapid rise of the collective farms.

The standpoint of the author of the theses of the C.C., Comrade Molotov, is a grave error. On this most important point we find him recently making the following erroneous statement:

“It is impossible, under present conditions, to fall into the illusions of the poor peasantry on the collectivisation of the broad masses of the peasantry.” (V. Molotov: “The policy of the Party in the village. State publishing office. pp. 64, 65.).

On the contrary, the best way to reorganise the millions of the smallest farming undertakings on the basis of socialised wholesale production is their collectivisation.

It is only when the poor peasantry are organised in collective undertakings that they can be helped economically to any adequate extent. The organisation of collectivisation among the poor peasantry must be made the chief task of our work in the village. This task cannot be successfully fulfilled unless both the Party organs and the village co-operatives and Soviets lend their aid, and unless the government grants sufficient means from the State budget to enable the collective undertakings being organised to be supplied with means of production on sufficiently favourable terms. The present grants made to the poor peasant funds, in themselves small, are split up among millions of small peasant farms, and utterly fail to render any real help.

Extensive grants must be made, systematically, from year to year for the purpose of giving economic aid to the poor peasantry organised in collective undertakings. A cadre must be formed of the organisers and leaders of the collectives, people from the village, and knowing the village thoroughly. Propaganda explaining the advantages of collective economy must be carried on in the village schools, and in the schools attended by the young peasants.

Considerable means must be expended on the organisation of Soviet farms.

At the same time the farms of those poor peasantry not brought within the sphere of collectivisation should be accorded systematic help by means of complete exemption from taxation, of a suitable policy regulating the distribution of land and the granting of credit for agricultural equipment, and by attracting them into the agricultural co-operatives, etc.

7. The Soviets.

28. The “instructions” of 1925, which gave the franchise to many of the exploiter elements in the village, were only a very crass our expression of how much bureaucratic apparatus, right up to its highest ranks, endeavours to satisfy the claims of the prosperous upper strata of the peasantry, which is accumulating wealth and enriching itself.

The cancelling of these instructions, which indeed violated the Soviet constitution, was the incontestable result of the criticism of the Opposition. But the first re-elections on the basis of these instructions showed very clearly the endeavour, assisted from above, to narrow down to the utmost the circle of those not entitled to the franchise among the better situated strata. However, the centre of gravity has since shifted from this point. The uninterrupted increase of the specific weight of the new bourgeoisie and the kulak, their rapprochement to our bureaucracy, and the false course steered all round, have given the kulak and the NEP.-man sufficient opportunity, even without the franchise, to exert influence upon the composition and policy of at least the lower Soviet organs, whilst remaining themselves behind the scenes.

The penetration of the kulak elements, or of elements “dependent on the kulak”, and of the city petty bourgeoisie into village itself (increase of population and splitting up of agricultural undertakings, causing 38 per cent of the peasant farms to buy grain in the surplus producing areas), in the disparity between the prices for industrial and agricultural products, and in the rapid accumulation of stocks by the kulaks. This leads to the predominance of barter in agriculture in general, and to a special growth of the accumulation of goods among the kulaks.

Even the Five Years’ Plan drawn up by the State Planning Commission is obliged to recognise that the “general shortage of industrial goods places a certain limit to the equivalent exchange between town and country, since it reduces the possible extent of the sale of agricultural products on the market (page 177). This circumstance undermines the close connection between town and country, and accelerates the differentiation of the peasantry.

33. The theses of the C. C. declare: “Although the general policy pursued is perfectly correct, and agriculture is being influenced to a steadily increasing extent by the Proletarian State, through its organs, through the co-operatives, etc., there are still a number of serious defects, mistakes, distortions, and sometimes unheard of violations of the political line of the Party.”

Only the second half of this assertion is right. It is precisely the general policy of the C.C. which has been wrong. Hence the inevitableness of the “mistakes”, the “distortions”, and the glaring defects appearing in actual practice. It is the C.C. which determines our policy, and its attempts to cast the blame for its errors onto the State offices and organs is unworthy.

In enumerating those organs which have “distorted” the Party line (land organisations, co-operative organisations, agricultural credit organisations, People’s Commissariat of Finance, State buyers, etc.) the C.C. condemns itself. Everybody is to blame except the C.C. The enumeration of the “guilty” and the character of the “distortions” fully confirm the correctness of the criticism by the Opposition of the whole line of policy adopted by the C.C. in the village. It is not a matter of single errors committed by this or that office, but of the general lines of guidance laid down, with all their vacillations, zig-zags, and deviations from the class line. It is not the errors of the offices alone which must be put right, but first of all the general line of the C.C.

The “concentrated fire” against the alleged anti-middle peasant deviation of the Opposition has in actual fact led to the unfettering of the economic power of the kulak, to the strengthening of his influence over a considerable section of the middle peasantry, and to the further enslavement of the village poor.

The incorrect policy of the Party in the village must be changed, and this cannot be done without a direct acknowledgment of the errors of the line pursued during the last two years, and a decided condemnation of these errors.

The C.C., in maintaining that it has always pursued the policy of “attack on the kulak”, is asserting something obviously not in accordance with the facts, for its course has not only failed to restrict the rise of capitalism in the village, but has enabled it to rise. It is just for this reason that the slogan has now to be proclaimed unexpectedly for the Party declaring at least in words that a “forced attack upon the capitalist elements, especially upon the kulaks, is necessary”. This is the slogan of the Opposition, and this is the right slogan! But the C.C. takes it ever much too late, from the Opposition, and is not even sincere in taking it over! The Party cannot feel confident that the leaders who have carried on a diametrically opposite policy for two years, are now really able and willing to follow this oppositional slogan. The practical execution of this slogan involves the recognition of the proposals of the Opposition.

In the class struggle going on in the village, the Party must lead the way, not only in words, but in deeds, and must unite the agricultural labourers, the poor peasants, and the main mass of the middle peasantry, in organisations enabling them to fight against the attempts at exploitation by the kulak.

34. Out of a total number of 32 million wage earners in the village 1,600,000 are agricultural labourers, men and women. Only 20 per cent of the agricultural labourers are members of trade unions. There is scarcely any attempt at the registration of the invariably enslaving wage agreements. The wages of the agricultural labourer are generally beneath the State minimum, even in some cases in the Soviet farms. The average real wage does not exceed 63 per cent of the pre-war wage. The working day is seldom shorter than 10 hours, and in most cases it is in reality unlimited, Wages are paid irregularly and after long delay.

The extremely hard position of the agricultural labourer is not merely the result of the difficulties of building up socialism in a backward agrarian country, but is at the same time due to the false line of policy which in actual practice, in deeds, in real life, favours the upper strata of the village and not its lowest. An all round systematic safeguard of the interests of the agricultural labourer is imperatively necessary, and not only against the kulaks, but against the so-called powerful middle peasants.

35. An urgent necessity is the systematic and efficient organisation everywhere of the poor peasantry, enabling them to take part in the most important political and economic tasks, such as the elections, taxation campaigns, influence on the distribution of credits, machines, etc., regulation and utilisation of the land, co-operation, realisation of the funds for establishing co-operatives among the village poor, etc.

The participation of the village poor in our endeavours will be an empty phrase until we have created a really powerful organisation of the poor peasantry, and have clearly defined their rights and duties.

The agricultural labourers must of course possess a completely independent class organisation (outside of the Soviets and the co-operatives). This is the trade union.

The main mass of the middle peasantry must be organised around the village Soviets and around the cooperatives.

But the village poor, precisely because they are the village poor, require a supplementary organisation (outside of the Soviets and the co-operatives).

All fundamental dealing with the regulation and utilisation of the land, or with taxation and the policy of the Party in the village must be submitted beforehand for discussion to the conferences and congresses of the village poor and agricultural labourers.

The conferences and congresses of the agricultural labourers and village poor are not be convened merely occasionally, but systematically.

As a counter-active force against the endeavours of the uppermost stratum of the peasantry, the kulaks and the well-to-do farmers, towards the formation of a “Peasants’ League”, which can only play a counter-revolutionary rôle, these congresses and conferences of the village poor must lay the foundations for the organisation, under the leadership of our Party, of a “League of the Village Poor”, in which proletarian influence is secured, and which must be a support for the dictatorship of the proletariat in carrying out its policy in the village.

In view of the increasing acuteness of the class struggle in the village between the poor and middle peasantry on the one hand and the kulak on the other, this league of the village poor must establish friendly relations with that main mass of the middle peasantry which is struggling against the kulak; the league of the village poor, in supporting the middle peasantry on all sides in this struggle (in the co-operatives,, the Soviets, and the like), will create a centre for the concentration of that main mass of the peasantry which is ready to join the Soviet power in building up the socialist village, against the kulaks, against the speculators, and against the capitalist elements of the village.

36. The Party must promote the economic uplift of the middle peasant by a correct policy with regard to purchase prices, by the organisation of credit accessible to the middle peasant, and by means of co-operatives, at the same time guiding this numerically greatest stratum of the village systematically and gradually to the transition to mechanical collective wholesale economy.

37. The task facing the Party with regard to the growing kulak strata consists of putting a stop to attempted exploitation at every point. No deviation is permissible from those points of our constitution which deprive the exploiting strata of the village of the franchise. Urgently necessary are: sharply graduated progressive taxation; State legislative measures protecting wage earners and regulating the wages of agricultural labourers; correct class policy in the sphere of land regulation and utilisation; safeguarding of the village poor against agreements reducing them to serfdom, and especially legislative protection in lease questions of peasants with little land. The whole policy of supplying the village with machines must be altered in such a manner tact the village poor be better provided than has hitherto been the case.

38. The views of the Opposition on the disputed question of peasant policy have proved to be entirely correct. The partial improvements introduced into the general line under the influence of the severe criticism of the Opposition do not prevent the official policy from inclining towards the “powerful peasant”. It suffices to mention that the Fourth Soviet Congress, after Kalinin’s speech, did not refer with one word to the differentiation in the village or to the growth of the kulak.

This policy can only lead to one result: the poor peasant will be lost to us, the middle peasant will not be won.

The theses of the C.C., in spite of the outward “Leftness” of some formulations, bring no change in the policy of the C.C. The exemption of a further 10 per cent of the village poor from the agricultural tax has been taken over directly from

the platform of the Opposition. This measure is correct, but insufficient. The “attack” announced on the kulaks has again been borrowed from the arsenal of the Opposition. The fundamental standpoint of the C.C., which denies the fact of capitalist differentiation in the village, and throws a veil over the processes actually going on in the village, is, however, bound to lead in actual practice to false and opportunist steps. The Central Committee forms a false estimate of the village, and this deprives it of the possibility of pursuing a correct Leninist policy in the village.

Left phrases and Right actions have always been characteristic of all opportunists and centrists. The far-reaching exploitation of various points of the platform of the Opposition, whilst concealing this platform from the Party, and the simultaneous mass expulsion of Bolshevik-Leninists from the Party, this is a fundamental contradiction which not a single member of the Party can pass over.

Bakayev, Kamenev, Rakovsky, Yevdokimov, Muralov, Smilga, Zinoviev, Peterson, Trotzky.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly. Inprecorr is an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1927/v07n70-dec-12-1927-inprecor-op-alt-scan.pdf