One of the better reads posted here this week. Joseph Freeman travels to Florida in 1934 and compiles a movie from eighteen prose photos of its Art Deco hotels and its rampant real estate speculation; of its Jewish residents its anti-semitic, lynch-mob manners; its wealthy tourists and its poor white peons; a pervasive barbarism practiced against Black citizens, living not in neighborhoods, by Jim-Crow labor camps; its New Deal bureaucrats, grafting politicians, labor sell-outs, and new Communist activists. Freeman at his finest, showing how radical journalism can be done.

‘Florida: Empire of the Sun’ by Joseph Freeman from New Masses. Vol. 11 No. 3. April 17, 1934.

1.

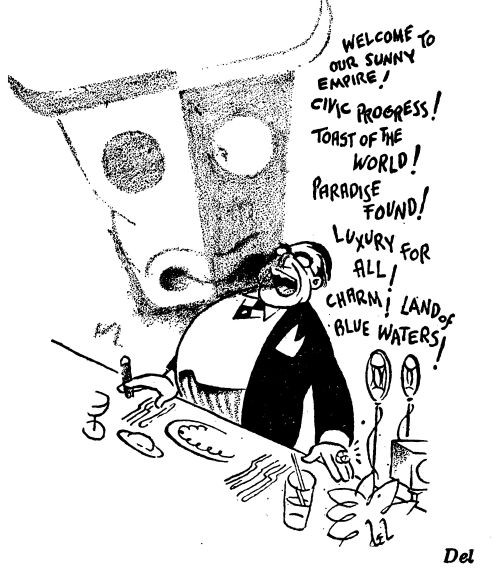

AUTO LICENSES proclaim–Florida: Empire of the Sun; and the ballyhoo of newspaper and screen have carried to every corner of the globe the glories and miracles of Florida sunshine.

Newspaper and movie cameras are trained almost exclusively on the life of the propertied classes. When we sit in northern houses surrounded by snow, scanning the Sunday rotogravure or the week’s newsreel, we are likely to be bewitched by the legend that Florida is solely a tropic paradise where American millionaires play in the sun while their slaves work and freeze.

The all-too familiar picture was summarized by the Miami Post last December in a special edition hailing the opening of the winter season. The front page, decorated with hanging palm leaves, carried on its borders conventional drawings of Miami life: two greyhounds race after an unseen mechanical rabbit; two women sun themselves on the beach, one in a deck chair, the other under a large sunshade beneath a palm tree; horses and riders gallop through a chukker of polo; a hydroplane shoots through the clouds; a girl leaps high in the air, slamming a tennis ball over the net; a slim figure of indeterminate sex dives into the water; two jockies lean over their horses in a neck to neck race; an idyllic tropical scene; a bridge with pagodas and the inevitable palm trees in the foreground; a golfer swings a club between two-palm trees; a motorboat races through the water behind a fat sailfish hurling itself into the air; three couples in evening clothes dance among palm trees; a girl rushes across the waves on a surfboard..

2.

Millionaire’s row bears the same relation to Miami as Park Avenue to New York. It is big in the news but small in area. A much greater section of the city is occupied by middle-class visitors. This year they have come from every part of the U.S.A. in greater numbers than ever, from the north as far as Maine, the west as far as California.

In the interior of the city, some distance from the luxurious hotels of the plutocracy, are the apartments and bungalows of small businessmen; they still have some money left after Wall Street’s raids but no business to occupy them. Here you will also find people living on small incomes who have returned from Cuba, Italy, and the Riviera. Conditions in Europe and Latin America are “unstable”–and foreign exchange is against the dollar.

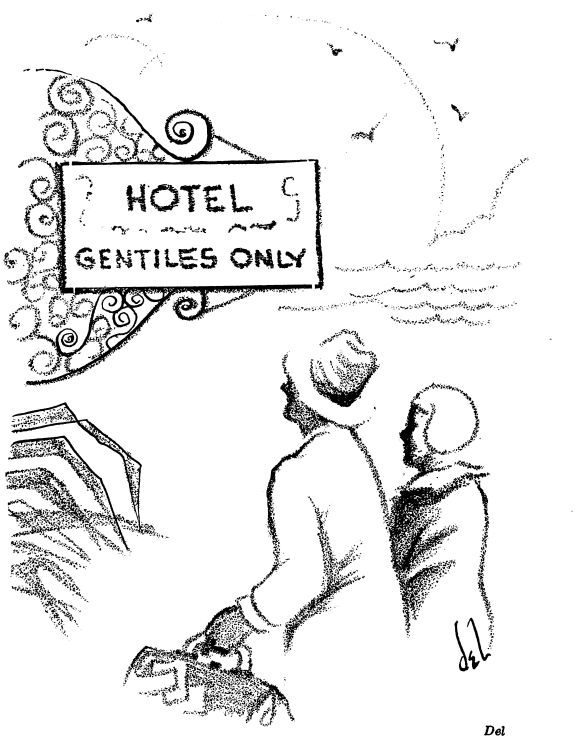

Around Washington Avenue is an extensive ghetto of middle-class Jews, segregated to some extent by an anti-Semitism which does not mask its hostility. The Martha Washington Hotel, in the heart of the ghetto, carries a large sign: Gentiles Only. Other hotels carry similar slogans in their newspaper ads.

The Jewish quarter is like Far Rockaway or Edgemere. In the more expensive hotels, such as the Blackstone, fat garment manufacturers and their wives ape the plutocrats of North Beach by playing the races and cards, showing off their costly, tasteless clothes in the lobbies.

On the tennis courts of South Beach you will find the type of school-teacher, accountant, lawyer who swears by the liberal weeklies and improves his mind at Cooper Union lectures. Some are here for their health; some because they are unemployed and–if you keep away from millionaire’s row–you can live more cheaply in Florida than in New York.

3.

A deep social gulf separates the petit-bourgeois section from the magnificent villas of the ultra-rich. Yet here, too, there is well-being and privilege. Garment manufacturers throw away on horse races money which they refuse to add to the wages of workers whose labor enables them to indulge in this waste.

A deeper social cleavage begins below these middle-class visitors, among the food-workers who serve the rich on the shore and the well-to-do in the town.

One can hardly speak of “wages” in the hotels and restaurants of Miami and Miami Beach. Where wages are paid at all to waiters and busboys they are extremely low; in many cases these workers are compelled to live exclusively on tips. The food which the hotels and restaurants give employees is frequently so bad they are forced to eat outside at their own expense.

The tipping system, degrading to the worker, places him at the mercy of extravagant pleasure-seekers who economize at the expense of those whose resistance is weakest. Men and women who spend ten dollars and up a day for a room, two dollars for a dinner, and hundreds of dollars on gambling, economize on tips which are the waiter’s sole source of income. The busboy, forced to live on a percentage of the waiter’s tips, is even worse off; I ran across one busboy who walked out of a restaurant in solitary protest because he had received $2.25 for a week’s work of twelve hours a day.

A waiter in one of the most luxurious hotels in Miami Beach told me as he was supping on a cheese sandwich and milk in a drug store:

“I get $15 a month and I’ve got to make a living on tips or croak. But the same guy that’ll lose $700 a night at Carter’s at roulette or stud poker will save money on me. The lousy food the hotel gives us has ruined my stomach. I’ve got to eat out. One day, when my stomach went very bad, I went to the Jackson Memorial Hospital. The first thing the doctor asked me was: have you got a dollar? When I said no, he refused to treat me. I live in Albany and haven’t got a cent to go home with. The worst is my family thinks I’m having a wonderful time here. They read in the papers about the millionaires and think that’s all there is in Miami. You can’t blame them. Millionaires make the news and waiters don’t.”

4.

Twenty waiters and 10 busboys employed by the Villa Venice walked out on strike March 13. The Villa Venice, owned by Mr. Albert Bouche, is one of the most exclusive cabarets on Miami Beach. Mr. Bouche charges his customers $2.50 for one dinner and three “elaborate presentations of Soirée Heureuse,” his “masterpiece,” the “show of 1939–five years ahead of the times.” The creator of “masterpieces” hired waiters at the beginning of the season on the promise that he would pay them $1.00 a day. The season came and went, but the waiters received no pay. They walked out on strike, the busboys with them. At this writing they are suing Mr. Bouche for back pay totaling $1,198.

The strike has run into a well-known snag. The only food-workers union in Miami is Local 133 of the American Federation of Labor, whose secretary is M.G. Drapkin. A militant young waiter, anxious for a victorious strike, urged Drapkin to wage a strong fight before the closing of the season left the strikers weaponless. Drapkin assured him the A.F. of L. was doing its best; it was handing Mr. Bouche’s customers Mickey Finns in their food. Not content with this all-sufficient strategy, the A.F. of L. officials called a meeting of the strikers at Union headquarters for the exact hour when their suit against the Villa Venice was to come up in court. Such is the policy of sabotage followed by the A.F. of L. bureaucrats who, in the true Miami Beach spirit, spend most of their time playing poker and dice at Union headquarters.

5.

The population of Miami-winter visitors excluded–is about 110,000; the rest of Dade County has a population of some 40,000, making a total of 150,000. Of these, 60,000 or more are Negroes.

Dade County has about ninety miles of beach along the Atlantic; of these ninety miles there is not a single foot where Negroes are allowed to bathe.

The city of Miami is divided, like so many American cities, by a railway track. On the “other side” of the track, in the northwest section of the town, is the proletarian quarter, grimy with the shacks of “crackers,” Italians, Jews, Latin-Americans–but chiefly Negroes. These live in dark, dirty little wooden houses, often without doors or windows. The walls are so thin and rotten they look like paper.

The southern gentlemen who govern Miami do not clean the streets of the Negro section; it is as filthy as millionaire’s row is spotless. Garbage is not removed for weeks, and the garbage piles rise like hills in front of the fragile shacks. A young local Communist, pointing them out to me, said ironically:

“These piles of garbage are so high that if you stood on one of them you could see the tower of the Roney Plaza Hotel.” Then he tower of the Roney Plaza Hotel.” Then he added: “Florida is at sea level; these garbage hills are the only elevation we have.”

6.

Prior to the economic crisis, the Negroes of Dade County worked chiefly at unskilled labor. Such labor was plentiful, especially during the boom stimulated by bankers interested in inflating Florida real estate. When the crisis threw most of the white skilled workers out of jobs, they took unskilled work which until then they had scorned as fit only for Negroes.

The local businessmen have encouraged this racial economic war. The Community Chest and various charity organizations gave white workers “unemployment relief” by throwing Negro workers out of their jobs in hotels and

restaurants.

Today most of the Negroes in Miami are unemployed. You can see them standing along the streets of the Negro ghetto or jammed in employment agencies asking white passers-by for work.

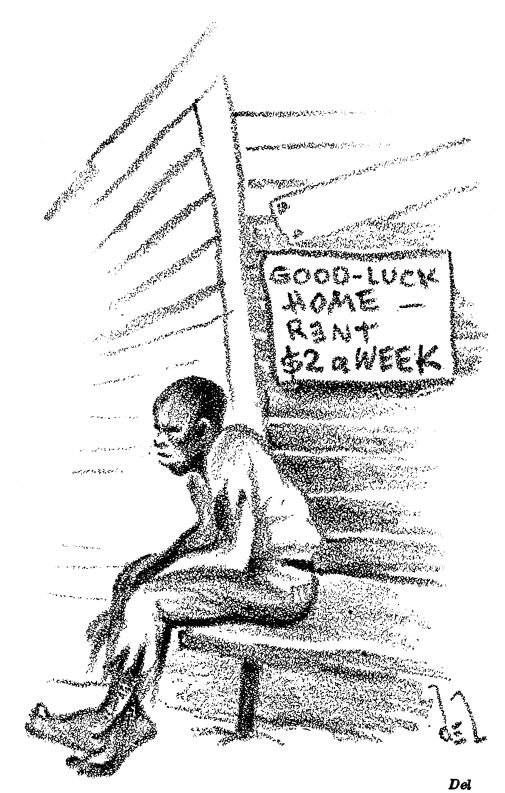

Mostly they sit dejected on the rickety porches of their shacks which sometimes carry crudely painted signs: Good Luck Homes–Rent $2 a Week.

7.

Miami Beach was planned and built as a pleasure resort. Its swankiest section is the playground of the American plutocracy whose imitation French and Spanish villas and hotels exceed in cost and comfort the palaces of Roman emperors, Renaissance princes, and European profiteers.

The cult of sea and sun dominates this ostentatious world. Like California, Florida employs the quack phrases of pseudo-science to advertise the miraculous cures effected by sunlight. You hear a great deal of twaddle about healthful sunrays, ultra-violet rays, actinic rays, and some obvious sense. Leading hotels display bulletins announcing the day’s temperature in various of the world’s sunny cities. Usually these bulletins show Miami ahead of Los Angeles, Nice, Cairo, Algiers.

The sea, too, has its devotees. From various docks, 300 Gulf Stream trolling boats, deep-sea fishing yachts, excursion boats and houseboats are “continually carrying voyagers to the happy fishing grounds along this glamorous coast.” Credit for that last poetic phrase should go to the Miami Chamber of Commerce.

Yachts named with justice after celebrated pirates take the buccaneers of American industry and finance to the Florida keys where the buccaneers of an earlier period found their winter playground. The Vanderbilts, Wanamakers and Astors follow the vacation trails of Captain Kidd, Black Caesar and the original pirate named Morgan.

Poor folk fish from bridges. Motoring along the west coast from Naples to Tampa, you can see them on every bridge with bamboo fishing rods, whites on one side of the bridge, Negroes on the other.

8.

Last year the federal government set up an Emergency Relief Council in Dade County to carry out the “New Deal.” The Council was in the hands of white politicians, charity organizations and churches. organizations and churches. The Negroes were unrepresented.

Emergency relief work was set at three days a week, forty cents an hour. Wages averaged $7 a week. In theory, white and Negro were entitled to equal pay for equal work. Jobs were to be distributed to “worthy cases.” The right to decide which Negro was “worthy” of the blessing of emergency relief work was delegated to the Negro churches, thereby increasing the hold of that reactionary institution over the Negro workers.

When the Emergency Relief Council was replaced by the Civil Works Administration, no change was made in the personnel of the Dade County administrators. The same local white politicians remained in charge of distributing work and pay.

Florida was allowed funds for employing 105,000 men. Paper plans called for certain C.W.A. projects in Negro neighborhoods, chiefly schools and sanitation. These projects were never started. Funds assigned for such projects were spent by the C.W.A. bureaucracy on itself in the name of overhead. At the same time Negroes were given only those C.W.A. jobs which white workers would not take, such as draining mosquito swamps.

At its peak, the C.W.A. employed about 6,700 men. Unskilled labor was paid 40 cents an hour on the basis of a six-hour day, five days a week. Skilled labor was supposed to receive wages at the prevailing market rate. In practice, such labor was underpaid twenty percent. Local trade unions finally protested and obtained the payment of prevailing rates in practice.

The differences in pay between so-called common and skilled labor opened the way for the customary corruption. Politicians, churches, charity organizations, American Legion chieftains placed their friends and members on the better paid jobs, regardless of qualification. The A.F. of L. in Miami protested against this practice and succeeded in obtaining a system of examinations for the better paid jobs.

One of the C.W.A. examiners assigned to this work told me that the new system simply created a labor racket for the A.F. of L. bureaucrats. They strengthened their own positions by handing out jobs to their henchmen. Eventually a triangular fight for the better paid jobs developed between the A.F. of L. labor “leaders,” the American Legion, and the so-called Dade County Unemployed Citizens League, which includes 4,500 unemployed workers misled by labor racketeers.

9.

The chief occupation of the “great and talented of many nations” who winter in Miami is gambling. Opposite the Roney Plaza Hotel, a few steps from the beach, is a stockbroker’s office where fat, sunburned men and women in bathing suits and brightly-colored bathrobes play the stock market.

Scattered along the beach are casinos where the “leaders of the nation” throw away on poker, dice and roulette enough in one evening to feed, clothe and house thousands of workers’ families for a year. At Hialeah Park and Tropical Park fortunes are thrown away on horse races.

At night the lovers of “sport” may rest from their labors at the ticker-tape, gambling casino and turf by betting on the greyhound races. I have not seen them, but a Chamber of Commerce pamphlet assures me they are “thrilling.”

10.

The corruption pervading the C.W.A. delayed much of the work. None of the important projects were completed on time. Federal and state investigations revealed “irregularities” in supplying labor and materials throughout Florida.

The federal government stepped in, suspended the C.W.A. and sent in Julius F. Stone, Jr. as acting federal administrator to prepare the way for a new federal-supported “relief” campaign. Stone suspended the C.W.A. work. The suspension, he explained, was to provide a breathing-space for transferring eligible workers from the C.W.A. work program to the new “relief” work program under federal control.

In discussions with the acting federal administrator, local white property-owners revealed with callous cynicism their hatred of the Negro. Why were C.W.A. funds assigned for educational and sanitation projects among Negroes not used for that purpose? Mrs. Meade A. Love, president of the Florida Federation of Women’s Clubs, explained: Many Negroes in Florida refuse to live in houses with glass windows; they prefer wooden shutters. Mrs. Love further explained: Negro children do not like to learn to read.

It seems that the Negro masses positively enjoy the misery forced upon them by the southern white ruling class.

Acting federal administrator Stone announced that under the “new” program the minimum wage would be 30 cents an hour. But he omitted to say that this minimum is for Negro workers. White workers are to receive 40 cents an hour. The federal representative, like the local white bourgeoisie, adheres strictly to the color line in emergency “relief.”

11.

Theoretically, Washington sent Mr. Stone down to “remedy abuses” in the distribution of relief work in Florida. Actually, there has been no change. Neither the federal nor the state government has the slightest intention of aiding the workers in the crisis.

Florida is back on the system of “emergency relief.” This system now operates as follows: A worker applies for relief. Thereupon an investigator visits his home and asks all kinds of relevant and irrelevant questions–the worker’s name, his wife’s name, the names of their respective parents, brothers, sisters and children. Are they American citizens?’ Where were their children born?

The investigator lists the minimum necessities of the family; he budgets its rent, groceries, clothing, insurance, debts, incidentals. Nothing is allowed for new furniture or depreciation of the old. Not one cent is allowed for doctor bills or medicine. The investigator is the one who determines the family’s needs; he, and not the worker or the worker’s wife, decides how much may be spent for the baby’s milk.

After deciding the budget, the investigator makes deductions on the basis of other sources of income. Has the family a boarder? Has it a boy who sells newspapers on the street? Has it chickens that lay eggs in the backyard? Any income in goods or money is deducted from the budget.

Two more rules: Only one member of the family can get work under the “emergency relief” system; no allowance is made in the budget for dues of any kind. The government does not formally forbid emergency relief employees from joining workers’ organizations; economically it makes it difficult for them to do so.

12.

The “new” system of “relief” has made several other “improvements.” The C.W.A. working time has been cut from five to four days a week. In the cities the total working time allowed is 24 hours a week; in the rural districts only 15 hours a week.

Emergency relief work is given for only one month at a time. But even for this period the worker does not receive his full pay. He gets only the amount called for by the budget determined by the investigator. The rest of his pay is kept for “relief” which he receives in instalments after he is laid off. But if after he is laid off, he should be working–it is reduced by an amount corresponding to what he earns at his new job.

Example: a painter working 24 hours a week under the emergency relief may earn $120 for the month for which he is hired. At the end of the month he is laid off. Instead of his full pay, he receives only the $60 (let us say) allowed by his budget. The remaining $60 is doled out to him as “relief.” But if after he is laid off he earns $35 at some other work, he will get in “relief” only $25. The worker will thus receive for his emergency relief job only $85 instead of the $120 which he earned.

13.

If the “New Deal” robs the white worker so shamelessly, it goes without saying that the Negro worker is even more brutally exploited.

At the rate of 30 cents an hour he may earn a maximum of $7.20 a week. Since he pays two dollars a week rent for a dilapidated shack, and corresponding prices for rotten food and does not need glass windows or schools, his budget is determined at less than $7.20 a week.

Living standards in the Negro section of Miami, “city of sun and happy hours,” are sub-human.

14.

The acute distress of the thousands of unemployed white and Negro workers in the “world’s greatest winter playground” has not prevented local politicians and labor “leaders” from celebrating the “success” of the “New Deal.” The first anniversary of the “New Deal” was observed by a parade on March 9. The chairman of the parade committee was F.G. Roche, an official of the Electrical Workers Union and the Miami Building Trades Council, both affiliated with the A.F. of L.

Fittingly the parade was headed by Major E.J. Close, director of work in the C.W.A. of Florida. With equal appropriateness, Stephen Early, assistant secretary to Roosevelt, wrote to a Miami paper that the President “is pleased to learn that Dade County I will hold a celebration in honor of the first anniversary of the New Deal,” and that he is “more than happy that the situation justifies such action.”

The President’s sentiments, as transmitted by his secretary, appeared in the March 2 issue of The Eagle, weekly organ of the Dade County Unemployed League. The same page which carried the President’s congratulations on the success of the NRA also carried the following statement by labor “leader” Roche:

“It is a sad commentary on Miami that so many of our business concerns are making little or no effort to comply with the provisions of the NRA.”

15.

It seems there is a limit to the kind of entertainment white visitors from the North may see in Miami.

Wometco Theatres, Inc., owned by a midwestern businessman named Mitchell Wolfson, runs the Harlem theatre, a vaudeville and movie house on Northwest Fourteenth Street, the heart of the Negro section. Current at the Harlem is The Brown Skin Models Revue. All the performers are Negroes, some of them from Shuffle Along, which ran in New York several years ago. The audience has, as a matter of course, been Negro.

Recently Wometco Theatres advertised in the Miami press that on Saturday night, March 17, a special performance of Brown Skin Models would be given exclusively for white patrons. About 2,000 whites appeared at the Harlem Saturday night, but they never saw the show. The police sent them home, saying that whites may not view a Negro performance.

This was Jim Crow in reverse. As a rule, Negroes are forbidden to enter white places, a Southern custom with which Northern visitors to Miami are acquainted; they were surprised to learn that the color line works both ways.

Wometco Theatres obtained an injunction restraining the police from interfering with a performance of Brown Skin Models for white patrons. In defending his right to make profits from white thrill-hunters, the president of Wometco Theatres completely accepted the southern attitude toward Negroes; discrimination against Negroes was all right with him. But, he argued, the Negro performers on the stage of the Harlem “are separated from the white audience by the footlights and might as well be a thousand miles away.” Besides, he did not intend to have mixed audiences or mixed performers. He was willing to maintain the color line; but if whites may attend Negro ball games and boxing matches, why not Negro revues?

The Miami authorities replied to Mr. Wolfson’s injunction and logic as follows: Fire Chief Westra suddenly discovered that the Harlem lacked an asbestos curtain and condemned it as a fire trap. At the same time the Miami city commission passed an ordinance prohibiting performances before white audiences by Negroes displaying any parts of their bodies other than face, neck, hands and arms. The ordinance placed similar restrictions upon white actors playing to Negro audiences.

To leave no doubt as to the sexual implications of the ordinance, the city attorney explained that its highly moral restrictions would prevent whites from attending Negro theatres, since “no white audiences would go to Negro shows unless they expected something unusual.”

These moves were effective. Wometco Theatres reached an “understanding” with the city officials; they agreed not to offer Negro shows for white audiences. The color line stays in Miami.

During the hearings on the case before the city commission, labor “leader” Roche appeared to urge that the proposed performance be stopped. He argued that Negro shows before white audiences are bound to cause “friction.” By this “testimony” Roche gained two points: he identified himself with the anti-Negro policy of ruling whites whose favor he curries, and he annoyed Wometco Theatres which refuses to employ A.F. of L. movie operators.

In halting Mitchell Wolfson’s attempt to exploit Negro entertainers for the benefit of white thrill-hunters and his own pocketbook, Miami city officials were no doubt serving the owners of cabarets and theatres in the white section of the city who fear to lose customers to Negro entertainment.

16.

“Boys,” writes a wag in a local weekly, “you’ll never become cabana boys at the ultra-ultra Surf Club of North Beach if you can’t meet the specifications of Alfred I. Barton, secretary. He insists his boys must be blonds and tall and slender, and very, very young, not more than twenty-three. The temperamental Mr. Barton, who is responsible for the beauty of America’s most artistic club, is very, very particular, mind you, on this score–and very, very annoyed when applicants do not come up to his requirements.”

Temperamental Mr. Barton is a good businessman. The rich and not always young ladies who loaf in the “artistic” cabanas of North Beach, striped with flaming colors suitable under tropic skies, like to have very young, very tall, very blond, very good-looking young men around.

17.

One night, on the road from Hollywood to Miami, we saw a truck crammed with Negro workers, men and women, many of them without hats and shoes, all of them in ragged clothes. They were crowded in the truck, standing up packed close together. They told us they were being brought from Georgia to pick tomatoes in Florida.

Curious. With thousands of unemployed white and Negro workers in Dade County, why should growers have to send to Georgia for tomato-pickers? The Miami newspapers shed no light on the mystery. According to the Miami-Herald, “not one Negro could be found in Miami’s Negro section who was willing to pick tomatoes at from $2.50 to $3April 17, 1934 a day. As a result, two trucks may be sent to Georgia in search for fifty Negroes to pick tomatoes on a 700-acre farm near Everglade City.”

This explanation only deepened the mystery. Why should Negro workers who stand begging for emergency relief jobs at $7.20 a week turn down jobs at $3 a day? The Miami-Herald story, however, hinted at the truth: “The grower, in need of pickers to harvest 300 acres of his 700-acre farm, appealed to the sheriff’s office for help in recruiting fifty pickers. Deputies I.R. Mills, Murry Grossman and R.B. Eavenson accompanied him to the Negro section.” The Negroes, as we have heard, refused to accept $3 a day jobs, despite the fact that the same story quotes W.H. Green, Dade County C.W.A. administrator, as saying that about 4,000 Negroes are registered with the C.W.A. but not one of them has been employed by the board.

Investigation in the Negro section revealed another story. The deputy sheriffs came not to offer $3-a-day jobs but to recruit forced labor. On March 26, this objective was achieved.

“Seventy-five Negroes,” the Miami-Herald reported the following day, “who were found loafing in pool rooms and on the street corners in the Negro section, were arrested yesterday by police in a series of raids and booked on charges of vagrancy. The raids were under the direction of Inspector Frank Mitchell and followed complaints that tomato growers in the Redland section have had to send trucks to Georgia to obtain Negro laborers to pick their crop…”

18.

Miami has A.F. of L. unions run by the usual type of labor-faker. There is also the so-called Dade County Unemployed Citizens League run by a gentleman named Meredith E. Fidler.

Mr. Fidler, arriving in Miami several years ago, hung around for a while among the left-wing groups which meet in the headquarters of the International Workers Order at 328 N.W. Second Avenue. The street runs through the workers’ section inhabited by Negroes, Jews, Latin-Americans, Italians, native whites. He suggested the organization of a debating society. When militant workers proposed instead the formation of an I.L.D. branch, Fidler fled and founded his League.

The League has 4,500 unemployed workers deluded by Fidler’s demagogy the object of which is to advance Fidler’s career in Miami politics. This has brought him into conflict with A.F. of L. bureaucrats who have similar ambitions.

The Eagle, official organ of Fidler’s League, carries the Blue Eagle and ballyhoos for Roosevelt and the NRA. Fidler is candid about some of his methods. The March 9 issue of his paper carried an article addressed to businessmen in which Fidler said:

“In order to further their efforts to relieve themselves, they [i.e., the unemployed citizens] have launched a paper called The Eagle, and if you will give it a little of your advertising, you may be surprised at the favorable results to them and to yourself.”

P.S. He got the advertising.

19.

Sunday, March 25, the Communist Party in Florida held its state convention in Miami. Eighteen representatives of Miami, Tampa, Jacksonville, Fort Lauderdale and other towns, elected two delegates to the national convention of the Party and outlined plans for future work. There were reports and resolutions on the organization of the Tampa tobacco workers; organizations of the unemployed, the farm laborers, the citrus workers, the Negroes, the longshoremen; the development of the Y.C.L. and I.W.O.; the circulation of the revolutionary press.

In the evening there was an open forum at the I.W.O. at which the delegates spoke informally about the convention and about Party work in general in the State of Florida. Most of the speakers were young, many of them of Latin-American origin, especially the Tampa group which included John Lima, a leader of the 1931 tobacco workers’ strike.

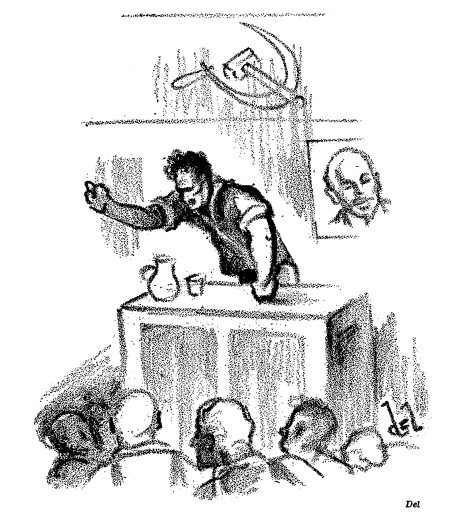

On the wall behind the speaker’s table hangs a large portrait of Lenin, beneath it one of William Z. Foster. A large book-case is filled with Communist books, in various languages; a small case, displays: The Daily Worker, THE NEW MASSES, Soviet Russia Today.

The speakers, young and old, men and women, talk quietly and seriously. A woman worker from a canning factory in Oakland Park, near Fort Lauderdale, describes working and living conditions of unusual misery which led to a strike and a wage increase. A waiter gives details about the Villa Venice strike in Miami Beach. A tall white farmer from the palmettas, with a bald head and smiling wrinkled face that reminds you of Gene Debs, tells how he organized 400 Negro land workers around Fort Lauderdale. A pale, young Latin-American with spectacles and an unusually intelligent face tells of the terror in Tampa, the organization of the tobacco workers.

All speakers stress the importance of organizing the land and industrial workers, Negro and white; of developing mass campaigns. Difficulties are analyzed: a brutal class terror prevails in Tampa, Jacksonville and other cities; the church dominates most Negro workers; race prejudice, fanned by the white ruling class, blinds most white workers. The Party in Florida is young and needs forces which must be nurtured in the state; mass organizations must be developed; open forums must be conducted.

Delegates point out that the work has only begun; but they give the impression that Florida has a militant group of Communist fighters who understand local problems and are determined to organize the struggle of the white and Negro workers against capitalist exploitation and oppression.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

For PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1934/v11n03-apr-17-1934-NM.pdf