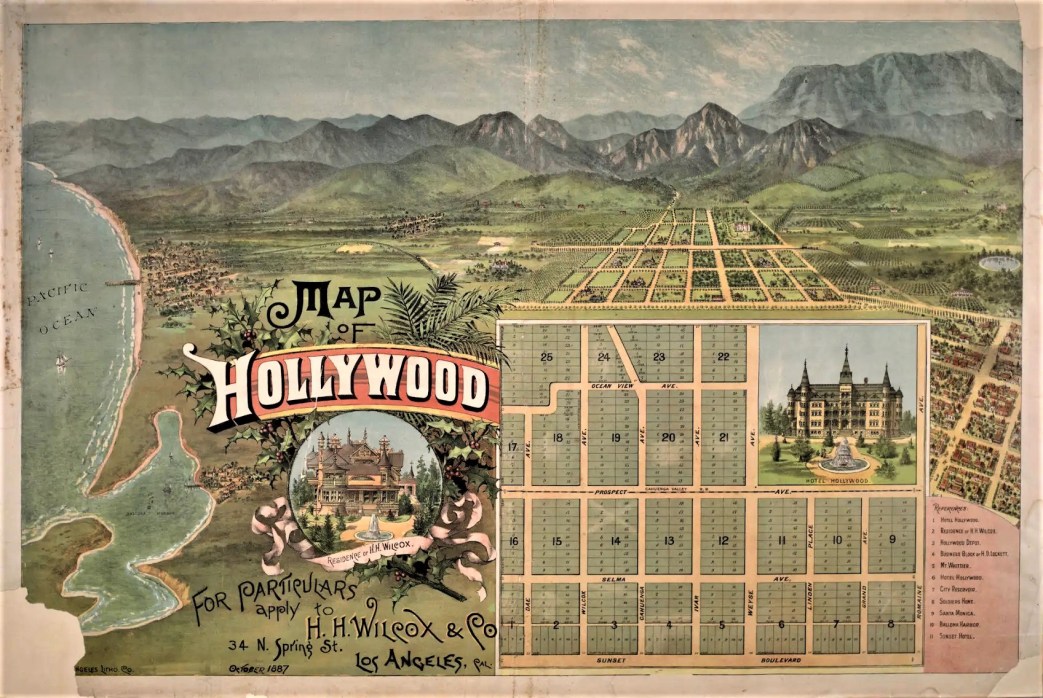

A superlative early look at the film industry and its workers. Julius Hess takes us on a tour of the workers and their conditions, from movie extras to film scrappers in the process of making movies for the culture industry. That industry moved from New York to the West Coast in the 1910s, and aside from working class history, this article is a wonderful snapshot of that moment and a gold mine of technological information on early film-making.

‘The Tale of the Movie’ by Julius Hess from the International Socialist Review. Vol. 17 No. 5. November, 1916.

IN its earlier days, when its possibilities were as yet not understood, the moving picture presented itself, from the workers’ standpoint, as an inaccessible and highly specialized industry. Only the few could break thru the barriers of influence which surrounded it and they, once belonging to the favored and highly salaried few, maintained a sort of sympathetic solidarity. They deluded themselves that, altho unorganized they could retain their standard, and even raise it, primarily because they were experts and few in number, and secondly because the moving picture industry could not, on account of the intense rivalry between the hundreds of small concerns, ever develop into the huge and dictating trust which it now inevitably is becoming.

But as the industry developed, the smaller companies soon found it more profitable to organize to produce their films. Instead of, as individual concerns, fighting furiously for actors, or photographic experts, etc., they organized their capital, three and four together, used one site as a producing ground and, as organized and concentrated exploitation, dictated the wages and conditions. Thus the “secure” and superior aristocrats of labor suddenly found themselves, instead of working a few hours for one company, working long and right lustily for several, at the same time facing a concomitant drop in wages. For instance, the Universal was a combination of twenty eight units. The Majestic became the Majestic, Reliance, Komic, Broncho, etc., all claiming the same address, and the concentration of capital went merrily on. Finally came the union of these small groups into larger ones, such as the Triangle Film Corporation, containing the Fine Arts (which formerly was the Reliance, Majestic, Komic, Broncho, etc.), the Ince and the Keystone. Companies of this caliber own their own theaters all over the country and are exhibitors as well as producers.

Meanwhile there had sprung up the “big feature,” such as the Clansman, which often necessitated the employment of thousands of people for one scene. Being at a loss to obtain these, the usual procedure is to connect with the Municipal Labor Bureau (I am writing of Los Angeles here), when a horde of unemployed are hurried out to work for $1 or $1.50 per day. After doing so these invariably burn with the desire to become movie idols, go to the company office and compete with the once high-salaried stock-actors and extras. These actors are now gradually perceiving that the cheap and despised mob-man is dragging the salaries down to his level, and thus the movie industry has become ripened for organization. But there are huge difficulties and to understand them it is first necessary to know something of how the movie is made.

Making a Movie

The studio is usually a series of small buildings, perhaps fifteen or twenty, collected together on a tract of ground commonly termed “the lot.” It represents a small town in itself, with cafeteria, barber shop, etc., and is even supplied with a town ”bull” to watch members of the extra fraternity who may become unruly during their search for work. The manufacture of the film itself is a more or less complicated process. The film is of celluloid, 1 3/8 inches in width, and is coated with a light-sensitive substance called the emulsion. Down each side of the film are the sprocket-holes or perforations which enable the film to be projected. As in ordinary photography, there are two varieties of film, the negative and positive. The negative is the original film exposed by the camera man, and from which any number of prints may be taken until the negative is worn out. Film is received from the Eastman Company, of Rochester, N. Y., in 400 foot rolls, a four hundred foot roll being about the diameter of a small plate.

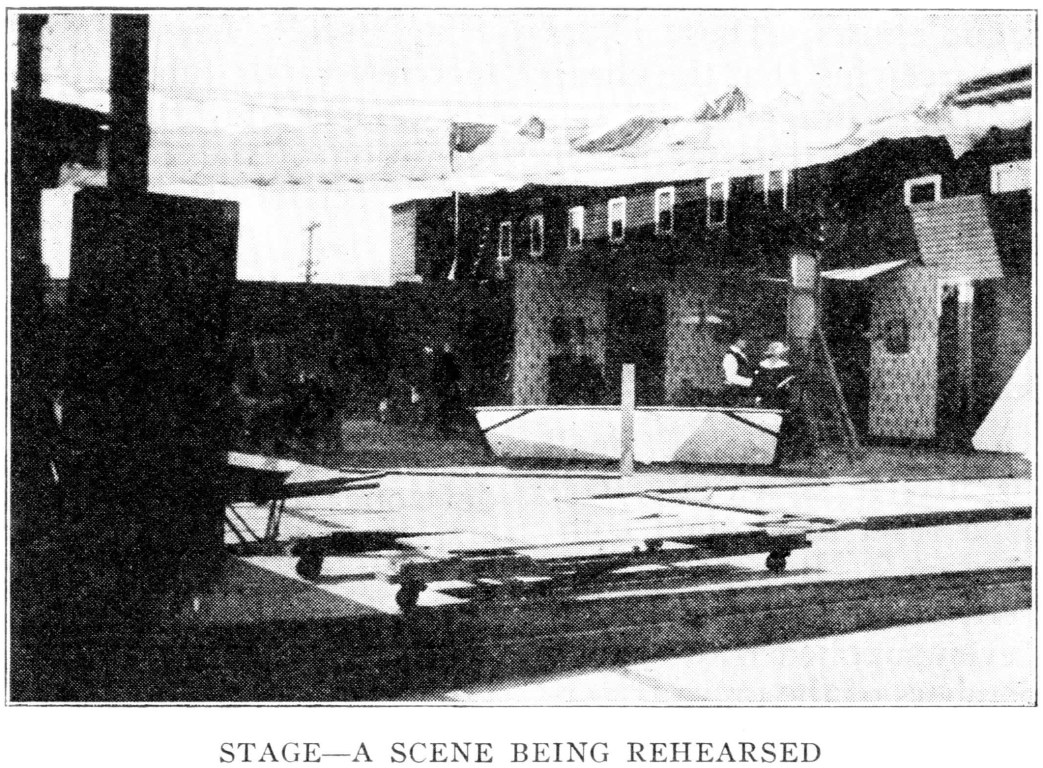

A scenario having been decided upon, a number of property men, carpenters, painters and helpers proceed to erect the first “set” (scene), which the director is to photograph. It does not necessarily follow that this is the first scene of the plot. Once a “set” is erected all the scenes which occur on it, during the progress of the plot, are filmed, without any sequence. So that sometimes one of the characters may be “shot” in the first scene taken, and then spend several weeks elaborating the plot which leads up to that event. After all the scenes in this room or rooms are taken the “set” is demolished.

Overhead are the diffusers, which are long strips of canvas laid upon wires, and drawn along by ropes. These enable the camera man and his assistant to regulate the quantity and locality of the light necessary for clear photography. Scenes are often taken at night time indoors, artificial light being used. These lights are a series of mercury-vapor tubes and a type known as the Cooper-Mewitt is generally used. The operation of these necessitates the services of a specially trained electrician and assistant.

When exposed the roll of negative is taken to the factory. The first process is to wind it around a square frame called a “rack.” This is next taken to a dark room and is placed in a wooden tank by a negative developer and developed. After being immersed in liquid the emulsion becomes soft and gelatinous; hereafter, until dried, it requires great care in handling as the least touch rubs off the emulsion and the entire roll may be spoiled and the scene would have to be retaken. Upon leaving the developer,’ the film goes to the hypo man, who makes it possible for the light sensitive surface to be taken out into the washing room. Here it is washed on drums revolving in water. Some companies use racks instead of drums for this purpose. All of the men who handle the film in the factory are skilled or semi-skilled. The cost involved in taking some scenes in large productions may be from $500 to $8,000, and it can be readily seen that the handling of a negative of this description involves great care and responsibility. A single false move, a touch on the jelly-like surface, and the entire scene is useless.

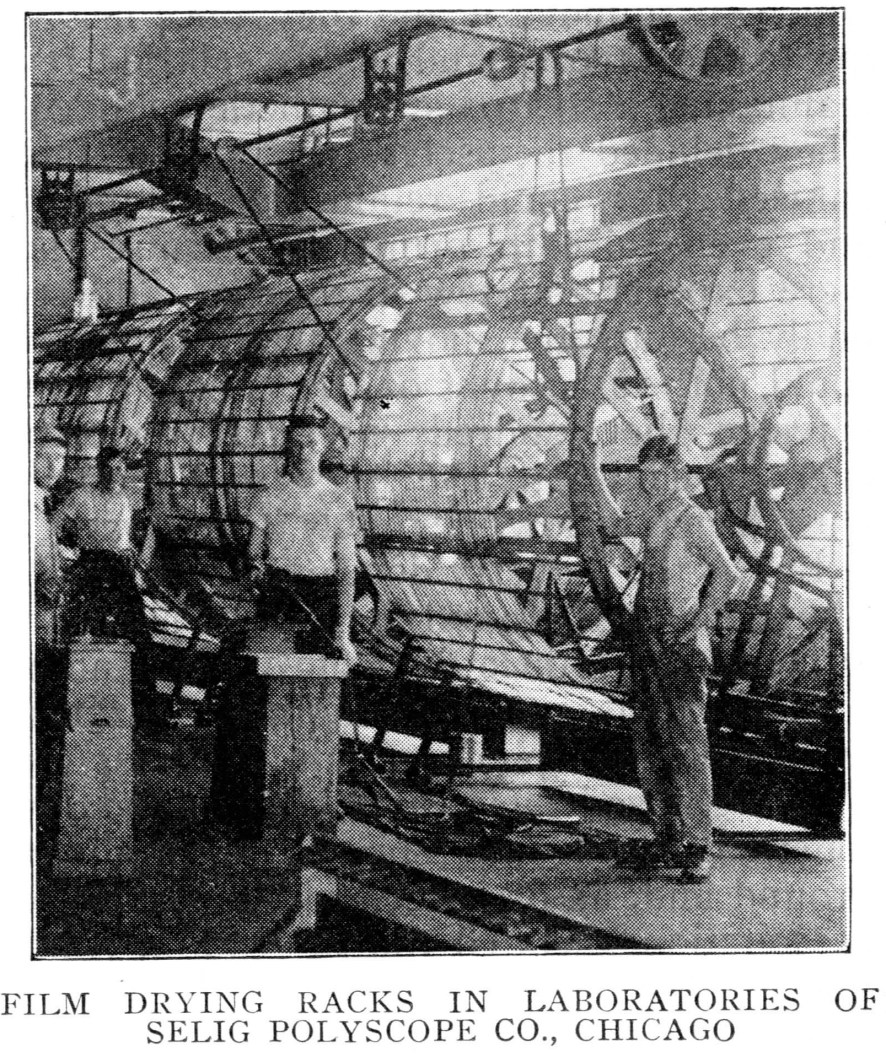

Having been developed, hypoed and washed, the negative is handed to the dryers who wind it on huge skeleton drums. There may be from twenty to thirty of these in the drying room and they are electrically driven. Revolving rapidly on these, in a high temperature, the film soon dries. Having been wound from the drum into a compact roll it is next taken to the negative inspection room. Here are girls who examine it on rewinders to see that there have been no scratches or rough handling during the chemical processes it has undergone.

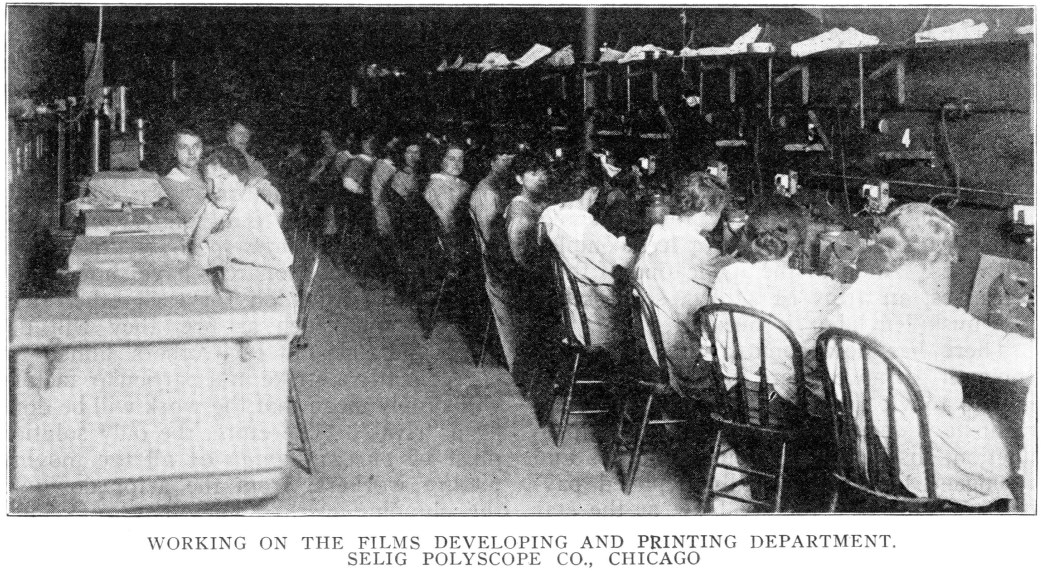

All being found correct, the printing room is the next to receive the roll. If you were to examine the negative now you would find that it resembles in appearance a kodak negative. The black portions are white and vice versa. The printing room is, of course, dark, that is to say lit only by red light. In it the printer takes our roll of negative and another roll of positive, places them together on the printing machines and reproduces the scenes from the negatives on to the positive. The positive film reverses the lights and shades of the negative and is the true film which is projected upon the screen in your theater. Nothing can as yet be seen upon it, for it too has to be developed. The process of developing, hypo, washing and drying is similar to that of the negative. The positive developing, however, is distinct from the negative developing, and is a trade in itself. Positive film is invariably colored. This is done on a rack, while still wet from the washing room and before drying. Analine dyes are generally used. The coloring of film, since the war, has become increasingly difficult as the cost of dye has increased as much as 750 per cent. We now see that the film is completed in itself, but it still remains to be “assembled,” that is to say, the rolls placed in sequence, the titles in order, ready to be “spliced” or joined together. The inspectors do this work after first seeing that the quality is good, the density of the prints correct, and the coloring even.

The process of joining film together is semi-skilled work. First the scrapers, usually girls getting about $7per week, carefully pare off the emulsion at the junction of the scenes leaving the raw film exposed. Next comes the splicer who places the ends together and applies some amyl acetate. The action of this is to melt the celluloid, this softened part immediately hardens again and the scene is joined. There are approximately one hundred splices to be made in a thousand foot real, consequently the speed of a splicer determines her salary. It would take you between 12 and 20 minutes to see one of these reels on the screen.

The completed picture is now taken to a projecting room, which is a miniature theater, and run upon the screen to see if all is well. Then comes the shipper who sends it to the exchange that has purchased it. The exchange rents it to the exhibitor. Then one evening you pay your dime, the operator places the first reel upon his machine and the show begins.

Future of the Movie

Thus, it will be seen, that the complete production of a film, ready for screening, involves a number of more or less complex processes. And, for the application of these processes, an army of skilled, semi-skilled and unskilled labor is needed.

There has now come a time when, in common parlance, there is a “slump,” that is, the movie magnates, by mutual agreement have decided to practically cease production, discharge all their’ employees and re-engage them on a sadly depleted paycheck. This is a mighty blow at the star as well as the smaller salaried man. Whereas, previously, corporations were wont to struggle for the services of the more brilliant of the film luminaries, these are now forced to return, contracts having expired, at any wage considered sufficient by the concern. The Fox Film Company has been discharging employees of all kinds. So has the Lasky and the Fine Arts.

The only Moving Picture Union in California (outside of the Operators) is the A. F. of L. Laboratory Workers’ Union, recently organized and consisting of about forty members (there are approximately 4,000 laboratory workers in Los Angeles alone). It is composed mainly of washing room men, with one or two printers. They are all attached to the Lasky or Fine Arts Studios. The rest of the companies are untouched. The making of a moving picture, as shown, needs the skilled or semiskilled attention of about fifty different crafts (including actors). To completely tie up a factory it is absolutely necessary for all of these crafts to strike. Not only this; the movies monarchs have shown such a degree of affection for each other that, on occasions, such as fire, they will develop and turn out each others’ films. So consequently a strike in· a particular factory will simply mean that the work will be done by a “rival.” Therefore, the only solution must be one big union of all the moving picture workers, from the actor down to the shipping clerk. They have not individual companies to fight, but a gigantic trust and the battle for more and more of the fat profits cannot be won by an isolated strike against one particular concern.

Finally, this industry is becoming one of the largest in the United States. The few rebels I have come in contact with already realize the futility of a petty craft union among such a net work of little crafts. The I.W.W. has sought -and has not yet abandoned- the seeking to establish an industrial union of moving picture employees. Such a union is the only kind to achieve results, so it is to be wished that its birth will be soon and its growth rapid.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v17n05-nov-1916-ISR-riaz-ocr.pdf