As proof of its immensely contradictory character, both the best and the worst of the U.S. labor movement emerged from the Knights of Labor. Here, Debs on the once-vanguard organization in decline as new forms of organization supersede it.

‘The Knights of Labor’ by Eugene V. Debs from Locomotive Firemen’s Magazine. Vol. 13 No. 1. January, 1898.

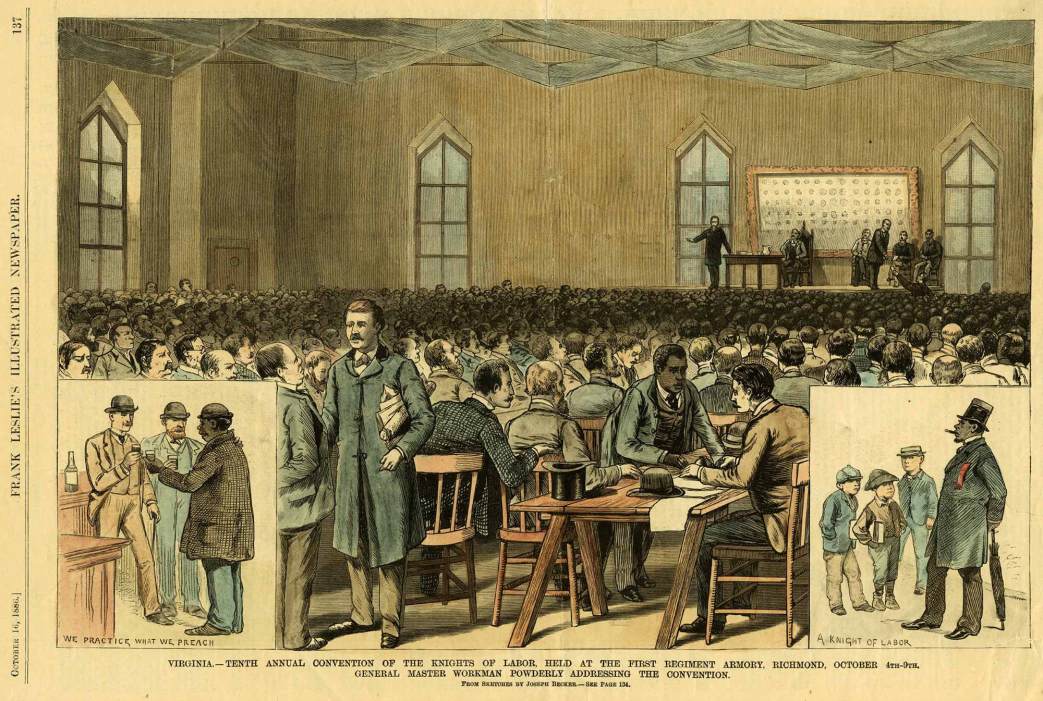

For a number of years past the organization known as the Knights of Labor, has been conspicuously before the country. Its rapid growth, its vast membership, its commanding influence in the industrial affairs of the country constituted the order an arbiter in matters of supreme importance to its members and their employers.

The membership at one time approximated a million. All men contemplated its colossal proportions with amazement, some with alarm. Its membership was composed of men and women, white and black, learned and ignorant, skilled and unskilled, working people. It aimed high. Its purposes were the amelioration of the condition of the working people of the country. It started out with the motto, that “an injury to one was the concern of all.” It was organized to strike. It believed in the boycott. It is not surprising that grievances were numerous. They existed in every department of labor.

Wrongs, more or less flagrant, were brought to the attention of the assemblies of the order. The course of procedure was sharply defined by law. Assemblies were clothed with extraordinary powers—designed, ostensibly, to correct abuses and improve the condition of the membership. If employers were stubborn a strike was ordered, and a boycott inaugurated.

The order is modern—and it is American. It sounded a keynote. It recognized certain great fundamental facts—the independence and the sovereignty of the American citizen. It grasped the vital idea that, if American wage workers were prosperous and content, the welfare of society was secure. If, on the contrary, the people, whose moral, intellectual, social, and physical well-being depended upon their wages, were underpaid, poverty and degradation would inevitably result, and that social disorder would follow with unerring certainty.

There is not a statesmen, a political economist, or a philanthropist on the continent, worthy of the name, who will controvert such propositions.

They are self-evident, they have the force of axioms—and yet, society as a whole, antagonizes the Knights of Labor. Not only Knights of Labor but every other organization of workingmen, whose purpose it is to better their condition pecuniarily.

If working people are content to accept such wages as are offered, and out of their scanty revenues provide assistance for the sick, bury the dead, and pay widows and orphans a few hundred dollars, when husbands and fathers are beneath the sod, society applauds. But the instant these wagemen complain of low wages, of poverty, of inability to provide the comforts and necessities of life for themselves and those dependent upon them, millionaires, monopolists, members of syndicates and trusts, bankers, speculators, food cornerers, and brokers, the entire brood of those who receive tribute from labor, set up the cry that workingmen constitute a dangerous element, the press is subsidized, the untold blessings which labor confers upon society are ignored and there are wild denunciations of labor organizations.

During the convention of the Knights of Labor in Indianapolis in November, some startling facts were made public, facts which all well wishers of this great organization must deplore. In the first place it was shown that the membership had astonishingly decreased—that at least 500,000 members had withdrawn. It was shown that there were internal dissensions, and worse still, that the order was virtually bankrupt—that its liabilities exceeded its revenues, and that financially, the order had reached the point of danger. To the superficial observer the conclusion is natural, that under such circumstances the organization had ended its mission, and nothing was left but to die as gracefully and as philosophically as circumstances would permit. We prefer to look upon a less gloomy side of such pictures. In the first place an organization with 300,000 loyal members ought not to be financially embarrassed, nor can it be for any extended period, provided a policy of wise economy prevails. The danger that confronts the Knights of Labor is not finance, but faction. The moment faction is eliminated harmony is enthroned, and with harmony comes health and strength.

Faction may reduce membership, but it cannot destroy principle. That there was a necessity for the order of Knights of Labor is not to be questioned. That it has made mistakes need not be asserted nor denied. That its mission is ended we do not believe. Its birth was not premature. Its phenomenal growth is convincing proof that the best interests of society demand its appearance. That it has waned is not a mystery. The reason why is easily understood, and the remedy is within reach. The head of the order, Grand Master Workman Powderly, has discovered the causes of decline, and in his address, points them out with such vividness that retrievement need not be delayed. That the Knights of Labor are sailing in dangerous seas just now, is patent to the most superficial observer. Mr. Powderly said in his address, that the deliberations and final conclusions of the late convention would seal the fate of the order; rescue it from death, or give to it new vitality. Most devoutly do we wish the order freedom from every entanglement that has reduced its membership, impeded its progress and threatened its dissolution. But whatever may be the fate of the Knights of Labor it will not arrest the determination of the wage workers of America to improve their condition.

For Freedom’s battle, oft begun,

Bequeath’d from bleeding sire to son,

Tho’ baffled oft, is ever won.

In the Indianapolis Convention, the fact was discovered that the Knights have an abundance of funds, and the prompt offer of financial assistance indicated a strong faith in the future of the organization. We are not disposed to criticize, pro et con, the amazing features of the meeting. It is enough to say that the organization remains intact, with Powderly at its head, and that we wish it the largest possible measure of prosperity.

The decree for the emancipation of labor has gone forth. It will not be modified nor revoked. Workingmen, like other men, will learn wisdom in the school of experience. If there are those who oppose and condemn labor organizations, and surmise that the disintegration of the Knights of Labor or any other union or brotherhood of workingmen means the triumph of those who antagonize such unions, they are doomed to disappointment. A Waterloo may have sealed the fate of Napoleon, but not of France. A Bull Run did not decide the fate of the Union. Revolutions may be arrested in their march but they do not move backward. The world may deprecate strikes, but they will come in some form until the cause for strikes is removed.

Go, wing your flight from pole to pole,

Nor cease till all the zones are seen

That belt the earth, where oceans roll

Where hills and vales are decked in green;

Find all the lands beneath the sun,

Where mountains rise and rivers run;

Where man for man has tolled and died;

Where tyrants have been defied;

Then tell me where the men are free,

Who have not struck for Liberty.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/details/188901FiremensMagazineV13/page/10/mode/1up?q=Knights