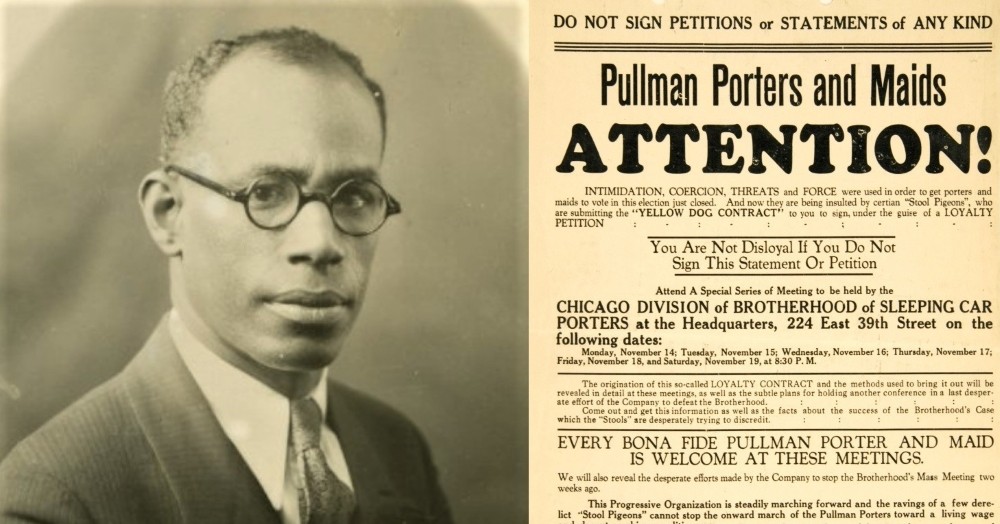

A leading organizer of the Brotherhood on the momentous campaign underway to organize Black porters and maids on the nation’s railroads.

‘A Year of History-Making’ by Frank R. Crosswaith from The Messenger. Vol. 8 No. 9. September, 1926.

August 25, 1925, has become an historic date in the annals of the American Negro and a date of more than passing significance to the workers of the United States in general. On the evening of that day a handful of Pullman porters betook themselves proudly to the basement of the Imperial Elks Hall, New York City, to listen to the message of trade unionism as expounded by A. Philip Randolph, Geo. S. Schuyler, the writer and others, and, to launch what is now generally recognized as the most challenging bid for a man’s chance ever made by the American Negro since his advent in the United States over three centuries ago. Facing what seemed to many as an insurmountable obstacle and an unbeatable foe, these men, on that eventful night “fired a shot” which has rivaled the one fired years before at Fort Sumpter in South Carolina. That shot from the South Carolina fortress was “heard around the world” and marked the beginning of the Civil War which was to end with the emancipation of the slaves. The one fired on August 25, 1925, by the Pullman porters, too has girdled the globe, carrying to all nations and races the glad tidings that a group of American Negroes had been introduced to the militant doctrine of trade unionism which would result in the direct emancipation of 12,000 Negro Pullman porters and maids from a condition of slavery but little removed from that of their forebears.

These Negro workers have been employed as porters and maids for nearly fifty-nine years. They have been known as the aristocrats of Negro labor. The actual condition of these workers does not, however, justify this claim. The movement to unionize them has brought to light the fact that Pullman porters and maids constitute the only group of workers whose position is so little removed from actual servitude and peonage that the difference is hardly recognizable. They are the largest and most outstanding group of unpaid workers of a race that is known as the unpaid workers of the world.

Not even in the convict labor-ridden Southland, or on the peon farms of that section of the country can one find workers who contribute anywhere from two to seven hours of labor without some sort of remuneration for the same, nowhere can one locate such a large number of workers, who are unable actually to tell what their wages will be five minutes before they receive it; nowhere are workers so thoroughly and systematically and so effectively exploited as in the Pullman service. They have suffered this fate at the hands of the Pullman Company which stands condemned before the world as having engaged in the wholesale and brutal exploitation of a race. Nevertheless, these workers facing obstacles unprecedented in the long record of workers organizing, have accomplished great things in the short space of one year. They have squeezed out of the coffers of the Pullman Company a slight wage increase. They have removed much of the haughtiness and arrogance which characterized the attitude of even the white office boys in the employ of the Pullman Company toward the porters and maids. They have won a higher respect and a more humane regard from the traveling public. They have made an immeasurable, spiritual contribution to the cause of organized labor. They have accomplished an educational feat of great magnitude among the workers of the Negro race as well as among the whites. On the whole, the Nation is richer today because of the birth of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters on August 25, 1925.

The experience of the Brotherhood during its year of infancy is not unlike that encountered by all other groups of workers making an attempt to win a fairer share of the product of their labor. The opposition of the Pullman Company was from the outset formidable. Having been permitted to exercise unquestioned the prerogative of wanton exploitation for nearly three generations, it was the most natural thing for the Company to oppose any

attempt that would interfere with what had become to them their unwonted right to breed and brutalize their Negro employees. In a vain attempt to stop the Brotherhood, all manner of “tricks” familiar to employers were resorted to: threats of dismissal from the service and in many instances actual dismissal, substitution of Filipinos on cars considered “choice runs,” the granting of a small wage increase, the harassing of the men by “stool pigeons,” “spies” and “spotters” all were called upon by the Company to do service for its cause. These having failed, the Company used what is considered among progressive trade unionists as the Bosses “ace in the hole.” It attempted to do to the Brotherhood’s organizer what it did to Eugene V. Debs, during the formation of the American Railway Union. Attempts were made to imprison him. Willing Negro tools were found who could (sic) do the trick; hastily drawn up indictments were secured only to be thrown out of court by fair-minded and honest judges. Efforts at bribery were also tried. The planting of men in the ranks of the Brotherhood to resign at what was considered “the strategic moment.” The lavish use of money to purchase the pages of some Negro newspapers to spread the poison of suspicion among the porters and the outright subsidizing of others, and many other gallant, but unsuccessful maneuvers of the Company to rout the little band of Brotherhood men away from their leaders and their Union back into the cesspool of low wages, long hours, inhuman treatment, and the manhood destroying habit of depending upon tips.

Against these onslaughts of a soulless corporation, the ranks of the Brotherhood stood immovable, adding to its roster large numbers of awakened black freemen with each setting sun. When the efforts of the opposition was most feverish and its strength appeared overwhelming, it was then that the membership of the Brotherhood grew with amazing suddenness, for example, when Ashley L. Totten was abruptly dismissed from the service, over 1,400 porters joined the Brotherhood, when the handpicked delegates at the so-called wage conference accepted the wage increase a score less than at Totten’s dismissal became Brotherhood men. When the Filipinoes were brought in to displace veterans in the service on Club Cars, the various headquarters of the Brotherhood were literally swamped with applicants. When Mays–whose place in history is as secure as is that of Judas Iscariot– resigned (sic) the Chicago representatives of the Brotherhood kept National Headquarters busy shipping applications and membership cards and other paraphernalia.

The Brotherhood has withstood the first 365 days of storm and stress, it has passed its babyhood days, its leaders and membership are richer in experience than they were a year ago. We have forged every stream, crossed every bridge, and met every exactitude with resignation and unflinching confidence. Whatever the future holds in store for us, be it hardship, privation, persecution, yea even imprisonment WE WILL NOT SURRENDER UNTIL THE RIGHT OF 12,000 PULLMAN PORTERS AND MAIDS to a living wage, shorter hours of work and a higher appreciation of their services is won.

To our Comrades in the struggle, to the militant soldiers of the Brotherhood, throughout the Nation, on every train, on every road, in every home, by every fireside, we doff our hats and extend genuine felicitation on this our first birthday, and we say, great as have been our accomplishments in the past, rich as has been the harvest we have reaped, let us at the threshold of a new year take courage afresh and pledge ourselves that we will strive for loftier heights and greater achievements during the year that is opening ahead. Other races have done it, we can do it if we so will. UPWARD, ONWARD, and FORWARD to our second birthday, resolved that we will stand united, one for all, and all for our BROTHERHOOD.

The Messenger was founded and published in New York City by A. Phillip Randolph and Chandler Owen in 1917 after they both joined the Socialist Party of America. The Messenger opposed World War I, conscription and supported the Bolshevik Revolution, though it remained loyal to the Socialist Party when the left split in 1919. It sought to promote a labor-orientated Black leadership, “New Crowd Negroes,” as explicitly opposed to the positions of both WEB DuBois and Booker T Washington at the time. Both Owen and Randolph were arrested under the Espionage Act in an attempt to disrupt The Messenger. Eventually, The Messenger became less political and more trade union focused. After the departure of and Owen, the focus again shifted to arts and culture. The Messenger ceased publishing in 1928. Its early issues contain invaluable articles on the early Black left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/messenger/v8n09-sep-1926-Messinger-RIAZ.pdf