A major reevaluation of Daniel De Leon. After the collapse of the Second International and the experiences of the Russian Revolution, pioneering U.S. Marxist Daniel De Leon and work, appreciated by Lenin, were reappraised in light of those experiences. Here is a substantial essay doing just that from Leonid Grigorievich Raisky, a former Red Army soldier who had become a Marxist historian specializing in the United States and became head of the History Department at Leningrad University. In addition to presenting De Leon, Raisky also takes us through an important era in U.S. working class history too little looked at today.

‘Daniel De Leon and the Struggle Against Opportunism in the American Labor Movement’ by Leonid Grigorievich Raisky from The Communist. Vol. 9 Nos. 9 & 10. September & October, 1930.

Translated by Povsner (1)

I.

At the end of the second third of the past century Karl Marx wrote, not without good reason, that the United States was a European colony. But how radically and with what unheard of speed has the situation changed! Already at the beginning of the ’90’s the United States, by the scale of its industrial production, firmly assumed the first place among the capitalist countries of the world, leaving far behind not only Germany and France, but also the “world’s workshop,” England.

The character and structure of American capitalism changed radically. A noticeable development of monopoly capital in the United States had already begun in the ’80’s. In 1879 Rockefeller founded the oil trust which was reorganized in 1882 along modern lines. Five years later a sugar trust, embracing twenty-one factories, was established. The victorious march of monopoly capital led to dismay among the middle and petty bourgeoisie who attempted to build a legal dam against the approaching “disaster.” But the Sherman law which was adopted by Congress in 1890 proved to be impotent in the struggle against the mighty economic elements: the growth of monopoly of capital was not stopped. Furthermore, it easily broke through the weak judicial barriers and confidently, irresistibly swamped the economic life of the country.

Where was the government at the time? How did it react to this attitude of the capitalists towards the Sherman law? What did the government do to combat the endless violations of this notorious law? It closed its eyes upon these “frolics” of the plutocracy. Moreover, it actively helped the bourgeoisie to evade the laws which were issued in order to hoodwink the voters. The only seal effect of the Sherman law was its unexpected interpretation by the Supreme Court in the sense that trade unions are organizations violating the “freedom of labor” and therefore non-constitutional.

After firmly capturing the decisive economic and political positions within the country, finance capital of the United States appeared in the 90’s on the world arena. In a chase for South American and Far Eastern markets, American imperialism took up with great vim the work of conquering the commanding heights of the Caribbean Sea and Pacific Ocean. As early as 1893, the United States virtually annexed the Hawaiian Islands. In 1898 American imperialism provoked a war with Spain, quickly and thoroughly defeating that country and annexing the Philippine Islands, Guam, Porto Rico, and establishing its protectorate over Cuba.

“Irresistible economic forces drive us towards the domination of the world!” By these words Senator Lodge formulated on the eve of the twentieth century the program of the youthful and avaricious American imperialism.

The United States was converted into a classic country of capitalist monopoly and imperialism.

II.

The sharp changes which developed in the social and economic life of the United States produced new conditions for, and a new character in the labor movement.

In the latter half of the ’80’s the power and influence of the Knights of Labor, the mass organization of the unskilled workers, reached its apex. Contrary to the position of the leaders who intended to solve the labor problem by mutual aid and peaceful cooperative development, the workers threw themselves into stormy strike struggle. This was a period of sharp class battles. The labor aristocracy took an extremely hostile attitude towards the struggle of the unskilled workers; they reacted with even greater enmity towards the attempt of the Knights of Labor to gain control over the unions of skilled workers. And when the bourgeoisie resorted to lockouts, blacklists and police terror in order to crush the Knights of Labor, the trade unions assumed an attitude of friendly neutrality, and sometimes even of active assistance to the bourgeoisie. By the united efforts of the capitalists, the government and the trade unions of the skilled workers, the Knights of Labor were suppressed at the end of the ’80’s, and in the ’90’s its remnants, which had lost the support of the masses, became converted into reactionary utopian groups that stewed in their own juice. The master of the situation from then on was the American Federation of Labor, the organization of the skilled workers.

After having been finally established in 1886, the American Federation of Labor, led by Samuel Gompers, John Mitchell, Strasser and others, at first flirted, though very platonically, with socialism, but soon forgot its youthful infatuation.

At the basis of its theory and practice the American Federation of Labor laid down the following series of principles:

1. The recognition of the indestructability of capitalism. The struggle for the every-day interests of the trade union members within the framework of existing society.

At the end of the nineteenth century the unoccupied land in the United States had been practically exhausted and the working man was no longer able to take up farming and become a property owner. How did the leaders of the American Federation of Labor react to this new situation? “The wage worker has now reconciled himself to the fact that he must remain a wage worker to the end of his life,” wrote John Mitchell, the vice-president of the American Federation of Labor, at the beginning of the twentieth century. “He has abandoned the hope for the future State in which he would become a capitalist (why necessarily a capitalist and not a member of the socialist commonwealth? —L.R.) so that his aspirations are limited to the desire that he as a worker should receive a compensation commensurable with his work.” (2) Fair pay for a fair day’s work—this formula expressed the entire concern of the trade union chiefs.

Replying to unjust charges of support of socialist theories, advanced against the American Federation of Labor by Professor Laughlin, Gompers wrote in the official organ of the Federation: “The unions have supported no other theory except the one which says that Labor is entitled to reasonable pay, a reasonable working day and human conditions of labor. … The literature of the trade unions is not socialistic. Ask the socialist leaders.” (3).

2. Class cooperation. “Hostility between labor and capital is not a necessity,” Mitchell’s argument continues. “The one cannot exist without the other. Capital is accumulated and materialized work, while the ability to work is a form of capital. There is even no necessary contrast of principle between the worker and the capitalist. Both are men with human virtues and vices, and both strive to receive more than their just share. But upon a closer examination the interest of the one appears to be the interest of the other, and welfare of the one the welfare of the other.” Mitchell saw the purpose of his book as that of convincing the capitalists to treat the workers “as tolerantly and decently as the latter treat them.”

Following the principle of class cooperation, Gompers and Mitchell joined in 1901 the American Civic Federation, a capitalist body officially designated to settle disputes between labor and capital, while in reality organized for the purpose of fighting the revolutionary labor movement. Gompers and Mitchell received from the American Civic Federation six thousand dollars per year each. Gompers was very proud of his official connection with the Civic Federation and always emphasized his full title: “President of the American Federation of Labor and Vice-President of the American Civic Federation.”

3. Purely economic methods of struggle. “What must be cured —the economic, social or political life?” Gompers asks in the American Federationist in September, 1902. “If the economic life is to be cured it must be done by economic and not by any other methods.” (4) To be sure the American Federation of Labor was by no means non-political; it merely opposed the independent political labor movement, preferring to make election agreements with this or that capitalist party and secure pledges to defend trade union interests in Congress (on the principle of “Punish your enemies and reward your friends.”)

4. The craft principle of organization. Every craft had its union. Paragraph 2 of the constitution of the Federation provided for “the foundation of national and international (5) unions, strictly observing the autonomy of each trade, and facilitating the development and consolidation of similar organizations.”

5. High initiation and membership fees. In January, 1900 Gompers wrote a complete treatise in an attempt “to prove by all means the fatal results of the non-establishment of high dues and proper revenues.” (6) The system of high dues had a double object. Firstly, it helped to create immense funds which were used for relief and insurance purposes; secondly, with their aid the trade unions firmly closed their doors to the poorly paid workers, this unruly element which constantly disturbed the principle of brotherhood between labor and capital, and dragged the trade unions into strikes which exhausted trade union funds.

6. The struggle against colored workers, who tended to degrade the standard of living of white American workers; the consolidation of the privileged position of the white Americans.

By this policy the leaders of the American Federation of Labor arrived at a situation in which ninety per cent of the workers remained outside the labor organizations and completely at the mercy of capitalist exploitation. But what are the sufferings of the vast masses of the workers to the Gomperses? They were perfectly indifferent to the contempt and hatred with which the revolutionary workers regarded them. But what pride Gompers took in the praise which the capitalists showered upon the craft unions and their leaders!

“For ten years I bitterly fought organized labor,” Gompers quotes Potter Palmer. “It cost me a good deal over a million dollars to learn that there is no more skillful, wide, devoted work than the one which is governed by an organization whose officials are level-headed men with the same standard…”

Melville E. Engels, the chairman of the board of directors of four great railroads, said, “It seems to me that your trade agreement offers the same protection to capital as to labor.”

Senator Mark A. Hanna, capitalist and politician, said, “Organize for no other purpose than for the mutual benefit of the employer and worker; do not organize in the spirit of antagonism.

I found the labor organizations prepared and willing to meet us more than half way.” (7) The same Hanna called the leaders of the craft unions “lieutenants of the captains of industry.”

It was under these conditions that De Leon developed his activity.

III.

Daniel De Leon was born in Venezuela on December 14, 1852, and was the son of a prosperous doctor. He was educated in Europe (Germany and Holland), where he studied modern and ancient languages, history, philosophy, and mathematics. At the age of twenty De Leon graduated from the university and soon went to the United States where he engaged in teaching and writing. In New York, De Leon enrolled in Columbia University, where he studied law. Upon graduating from the university he acted for six years as assistant professor of international law in the same college. De Leon’s academic career began brilliantly, thanks to his extensive and international education and oratorical gifts. He became very popular among the students and with the university administration, and was soon to gain the chair of full professor.

But this academic career ended just as dramatically as it began. In the middle of the ’80’s De Leon became closely interested in the labor and socialist movement. In 1888 he joined the Knights of Labor and later fell under the influence of the American utopian, Edward Bellamy. Soon, however, the utopian reform movement ceased to satisfy De Leon, who made a thorough and serious study of Marxism in which he found the answer to all the social problems which interested him.

The university administration then began to give attention to the fact that De Leon’s lectures were becoming imbued with socialist ideas. A conversation followed between De Leon and the president of the university, and when the latter began to explain to De Leon that science was neutral and apolitical, De Leon at once submitted his resignation.

From that time on De Leon completely broke with university circles and devoted himself entirely to the labor movement, placing all of his unusual gifts at its service.

In 1890 De Leon joined the Socialist Labor Party which adhered to a Marxian position, and thanks to his extensive learning, will power, fanatical devotion to the working class, and oratorical and literary gifts, he soon gained a leading position in this party. Thenceforth the history of the Socialist Labor Party became inseparable from the political biography of Daniel De Leon, just as the history of the C.P.S.U. is closely connected with the name of Lenin.

In a brief sketch it is impossible, of course, to describe the entire twenty-five years of De Leon’s socialist work, just as it is impossible in such a short space to give a full idea, of his theory of “industrialism,” which constitutes a retreat from Marxism in the direction of syndicalism, or, of his theory of the State, in which De Leon, one year before the first Russian Revolution, anticipated some elements of the Soviet system. We will also have to pass by the weak points of De Leon’s policy which suffered from the spirit of sectarianism. In this article we will limit ourselves to a description of De Leon’s resolute and difficult struggle against opportunism in the country of “classic” opportunism, in the country of the most backward labor movement.

American capitalism had a number of important advantages over the European capitalist countries. Possessing an abundance of raw materials and cheap fuel, the American bourgeoisie was able to develop a peculiarly American rate of capital accumulation. This was so also because the entire globe constantly supplied it with labor power. The United States did not have to make any outlays for the training of skilled labor, as the European capitalist countries were forced to do, but largely received this labor from outside. In addition, owing to the presence of vast unoccupied stretches of land in the country, there was practically no absolute ground rent and the bourgeoisie was not forced to divide the surplus value with the landlords; thus the American employers were richer than their European rivals.

The United States is one of the youngest capitalist countries and therefore made use of all the latest technical appliances. The American bourgeoisie was impelled constantly to improve the technic of production by the high price of labor. With the aid of the most modern machinery and the speed-up system the American capitalists squeezed out of the workers more surplus value than European capitalists. Two American workers produced as much as five British. Upon establishing a monopoly within the country, the American capitalists protected the domestic market from foreign competition by a system of high tariffs and converted the vast country into a field of monopoly super-profit.

All this enabled the American bourgeoisie to place the workers in better conditions than those prevailing in Europe. In the United States the highest wages have been historically established. Without this condition the bourgeoisie would not have been able to keep the necessary number of workers in the industrial centers, in the factories, mines and railways. The presence of free land made itself strongly felt.

But if the American proletariat represented a peculiar aristocracy compared with the workers in other lands, among the American proletariat itself there grew up a section of highly skilled workers (chiefly Americans) whom the bourgeoisie placed in specially privileged conditions and broke away from the rest of the working masses. It was this labor aristocracy which supplied the basis for Gompersism.

The awakening of the class consciousness of the American workers was also hindered by the following factors. The country had a considerable amount of free land which served as a refuge to the unemployed and discontented workers. True, by the end of the nineteenth century there was practically no free land left, but its existence in the past left a definite impress upon the psychology of the American proletariat.

The same effect was exercised by the democratic system of government and the competition between the two political parties. In the chase for votes both of these rival parties made some concessions to the workers and corrupted their consciousness. Finally, the ethnographic diversity of the American proletariat also had its effect. The American born white workers enjoyed better conditions compared with not only the Negroes, Chinese and other colored workers, but also the white foreign born workers. In this way the bourgeoisie strove to imbue the white American workers with a belief in the identity of the national interests of all Americans as opposed to those of all other races and nations.

In consequence of all of these factors the American labor movement became more backward, conservative and opportunistic than labor in Europe. In the United States there has historically developed a sharp contrast between the objective maturity of the country for socialism and the backwardness of the subjective factor.

IV.

In his theoretical and practical activities De Leon proceeded on the belief that the socialist revolution must begin in the United States, the country of classic capitalism, where the absence of any elements of feudalism has resulted in the highest type of capitalist relations, and where, therefore, the objective conditions for the socialist revolutions were more ripe than in any other capitalist country. (8)

If this is so, then it is necessary to use all forces for the preparation of the subjective factor. It is necessary to awaken the class consciousness of the proletariat, to organize it on an economic and political basis, and lead it to a strong attack on the capitalist fortress. This makes it necessary, first of all, to rearrange the forces of the Party, this “sharp point of the lance,” (9) this “outpost of the column.”

“In the revolutionary movement as in a storm attack of a fortress,” De Leon said in his address “Reform or Revolution,” in January, 1896, “everything depends upon the advance detachment of the column, upon the minority which is so persistent in its beliefs, which is based upon such healthy principles and is so determined in its actions that it carries the masses with it, storms the parapets and captures the fort. Such an advance detachment must be our socialist organization in relation to the entire column of the American proletariat. The army destined to win the victory is the army of the proletariat at the head of which must stand a fearless socialist organization deserving the love, respect and confidence of the army of the proletariat.” (10)

In the social cataclysm which is inevitable in the near future, all the petty bourgeois and reformist organizations will be swept away under the debris of the old world. Only the stalwart socialist party will firmly stand over the ruins; it alone will be capable of leading the masses. “But it will be able to achieve this only on a revolutionary basis; on a reformist basis it will never be able to be victorious.” (11)

De Leon proclaimed a merciless war upon reformism. Reforms, he said, marks a change of the outer forms only, while the inner substance remains unchanged. A poodle may be shorn to look like a lion, but it still remains a dog. Yet the wealthy and powerful American bourgeoisie has fully appreciated the demoralizing force of concessions and sops, while the capitalist politicians know the power of reform which serves as a safety valve, giving vent to the revolutionary sentiments of the workers, and as a trap into which the reformists are easily enticed by the bait.

De Leon considered it a “fatal illusion” to hold that capitalism can be gradually destroyed with the aid of palliatives. A tiger will furiously defend the ends of his moustache and will fight with even greater fury for his heart. This is an instinctive process. A sop is an “opiate prescribed for appeasement.” “A revolutionist,” De Leon wrote in his remarkable work Two Pages from Roman History (April, 1902), “must never throw a sop to the revolutionary elements. As soon as he does this, he will give himself up to the power of the enemy. For he can always be out-sopped. This happened to Caius Gracchus who proposed to create three colonies in order to improve the lot of the proletariat. The patricians rendered Gracchus harmless by introducing the demagogic proposal to create twelve colonies. This greater sop, which led to Gracchus’ downfall, was never realized; it fulfilled its narcotic mission and was cast aside.” (12)

As a striking example of blindness displayed by reformists, De Leon cited the telegram received by the Milwaukee Social Democratic Herald from Chicago on April 2, 1902. “The two-thirds majority secured in favor of the platform of the municipalization of property,” the telegram read, “testifies to the fact that socialism is in the air.”

The labor movement in Chicago gained considerable force; the soil there was ploughed up deeper than in New York, De Leon says; probably for this reason the capitalist politicians of Chicago were more “skillful” and “mobile” even than their New York colleagues. But even in New York individual politicians resorted to the “municipal ownership” plank for the purpose of camouflage.

“The fearless socialist agitation has acquainted public opinion, though still rather vaguely, with the socialist aspirations. The politician who is ‘broad-minded’ and in addition ‘alert’ does not object to the socialist elections. Being ‘alert’ and in addition ‘broadminded,’ he does not object to this procedure if he can take the liberty of giving a shadow instead of substance, especially if he can thereby kill socialism. ‘Municipal ownership’ is particularly useful for such purposes. It sounds ‘socialistic’; but we know that this term may be used to cover up an anti-labor scheme. The capitalist tales about its God-given ability to direct industry have failed, and now capitalism is seeking a quiet harbor in ‘municipal ownership.’ This is an ideal capitalist sop for those anxious to take any bait…Still the social democrat rejoices: “The two-thirds majority in favor of municipal ownership shows that socialism is in the air.’ ” “In the air,” De Leon mockingly agrees, “even too much ‘in the air’ —everywhere, except the soil of Chicago…”

Any sop thrown by a reformist to the proletariat is like the skin of a banana placed under the feet of the proletariat, which will cause it to slip and fall. “‘Not sops, but unconditional surrender of capitalism—such is the fighting cry of the proletariat revolution.” (13)

Up to the ’90’s the Socialist Labor Party developed very slowly, both quantitatively and qualitatively. The party consisted almost exclusively of foreigners, particularly Germans. It was characteristic that the central organ of the party was published not in English, but in German. The influence of the party among the American born workers was extremely weak.

Ideologically the party was only beginning to get on its feet. Only in 1889 was the demand for the material assistance of the workers’ associations by the State omitted from the program, a demand which was copied from the German Lassallians or, to be more exact, imported into America by the German immigrants. On the fundamental question confronting the party, namely, the question of the methods and platforms by which it could entrench itself in American soil and pave the way to the masses of native workers, two tendencies fought each other. One believed that it was necessary to give the main attention to socialist propaganda during elections, ignoring the trade union movement; the other saw the principal task of the party in the trade union movement, and neglected the political activity.

De Leon opened a struggle against these narrow, anti-Marxian tendencies, insisting that the economic and political struggle must be conducted simultaneously.

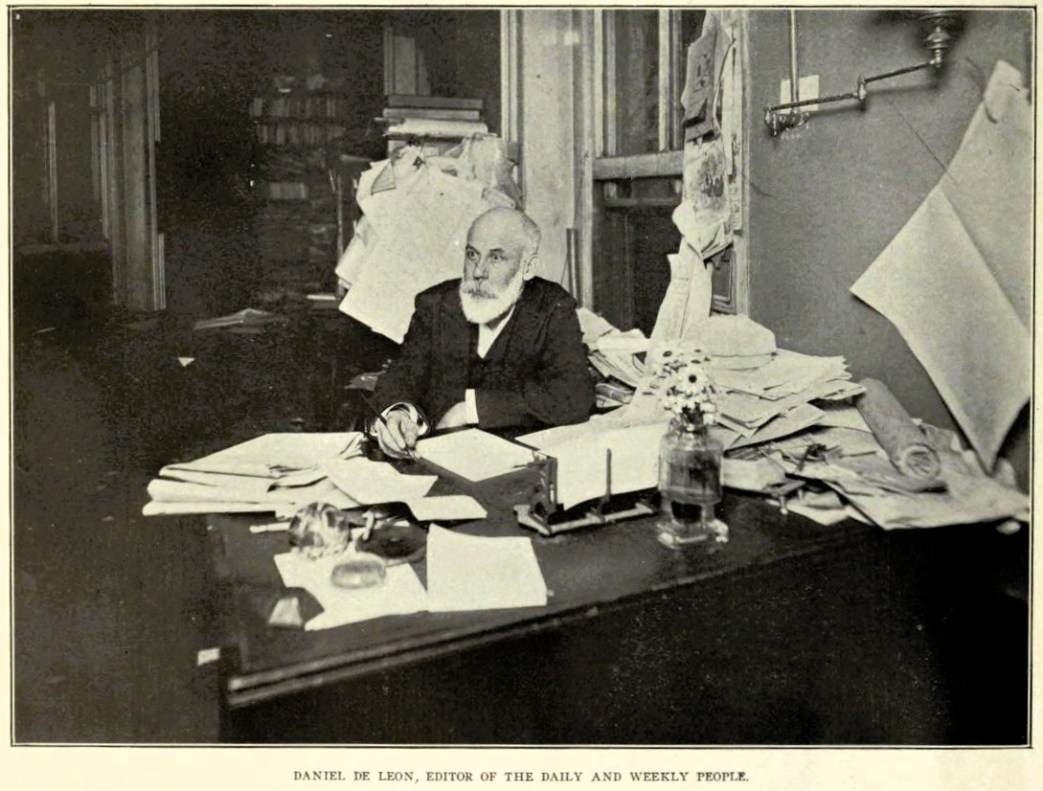

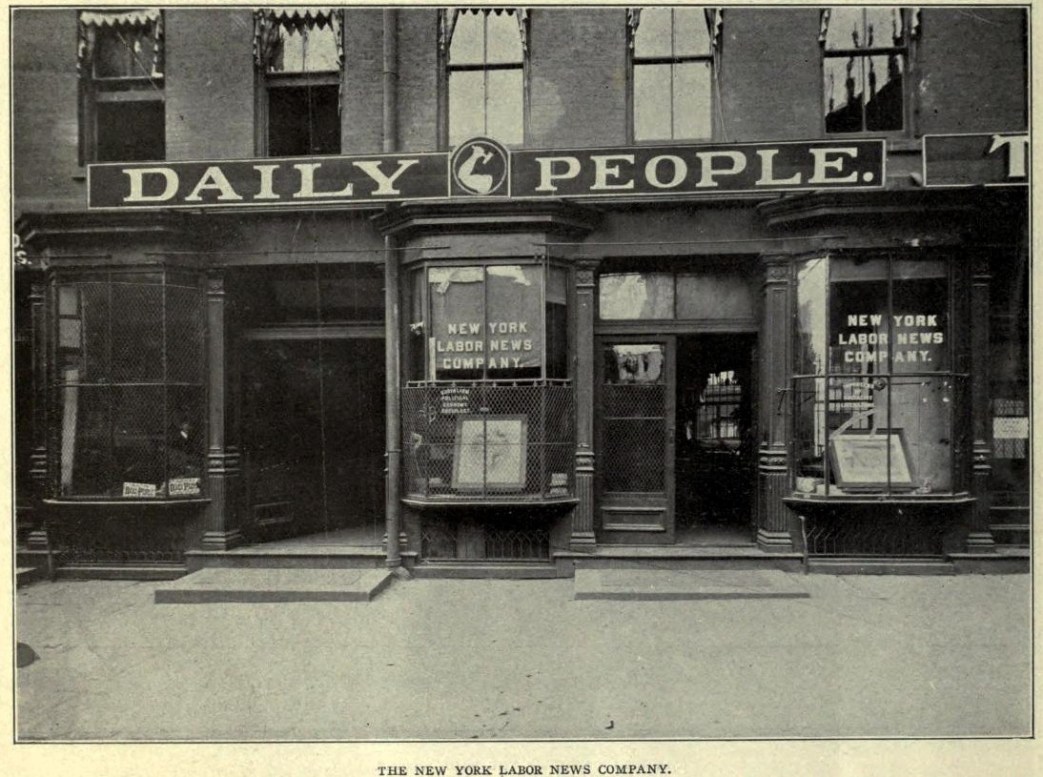

Under De Leon the central organ of the party for the first time began to be published in English, first as a weekly (The Weekly People) and nine years later as a daily (The Daily People). The newspaper was written not only for the workers but in a considerable measure also by the workers whom De Leon, as editor, attracted as correspondents. With the aid of the newspaper ably edited by De Leon, the party battered its way to the bulk of the American proletariat, educating and organizing its advance guard.

The triumph of imperialism, the taking up of the offensive against the masses of the proletariat by the monopolistic plutocracy created a favorable basis for an extension of the socialist movement in the United States. In the ’90’s the party, led by De Leon, entered on the broad historical highway.

However, the new conditions gave rise to new difficulties. De Leon’s determination to convert the party into a revolutionary militant vanguard of the proletariat met with resistance within the party, which led at the end of the century to a split and a segregation between the revolutionary and the opportunist elements in American socialism. During 1900-1901 the elements who were dissatisfied with the inner-party regime and the tactical principles defended by De Leon, constituted themselves into a new Socialist Party. At the head of this party were Morris Hillquit, Victor Berger, and others.

Originally the differences between De Leon’s followers and the supporters of Hillquit and Berger developed over inner-party questions and the attitude to be taken towards the trade unions. During the twentieth century the two parties drifted further and further apart, each of them developing its own conception of the structure of the future society, of the main roads leading to socialism, and the effect of parliamentarism.

VI.

Hillquit, one of the representatives of the anti-De Leonist wing of the Socialist Labor Party, who subsequently became the head of the Socialist Party, constantly complained about “the fanatical severity (of De Leon) in the enforcement of discipline.” (14)

Indeed, De Leon was absolutely unrelenting in the struggle against intellectualist individualism and in the fight for proletarian discipline. This logically followed from De Leon’s entire revolutionary position. If modern America is a battlefield, if the proletariat is one of the armies acting in this field, then the vanguard of the revolutionary class will solve its historical mission only if it enters the battle in full fighting readiness.

A comparison between De Leon and Lenin naturally presents itself to one’s mind. De Leon’s views on the inner-party question resemble Lenin’s even in the style in which they are expressed.

In his Reform or Revolution, which we have already cited, De Leon draws the following parallel between a revolutionist and a reformist:

“A modern revolutionist, that is a socialist, must primarily be obliged to work in the organization, with all of its applications. Here you have the first characteristic distinguishing a revolutionist from a reformist. A reformist scorns organization; his symbol is: Five sore fingers spread out far from each other.

“…A modern revolutionist knows that in order to obtain results or push forward a principle it is necessary to have unity of action. He knows that unless we create an organization and stand together we will hang separately. That is why you will always find a revolutionist submitting to majority rule…That is why you will never find a revolutionist who regards himself above the organization. The opposite behavior constitutes an unmistakable characteristic of a reformist.

“…The highest individual freedom must go hand in hand with collective freedom, which is impossible without a central leading authority…A reformist always shouts against ‘tyranny,’ but just watch him; give him a free hand and he will always strive to get on top, to become a rider, an autocrat, whose whim must be law…The fickle reformist is governed by centrifugal force, the revolutionists by centripetal force.” (15)

De Leon never sacrificed quality to quantity, principle to numbers. “The conception that the main thing is quantity and not quality frequently leads to absurd results,” he said. (16) This principle, as applied to the party, prompted De Leon mercilessly to drive out of its ranks all those who in any way retreated from its fundamental principles, for, he maintained, “undermine the discipline, permit this member (of the party) to do whatever he pleases; permit another member to fly in the face of the party constitution, a third to merge with the reformists, someone else to forget the nature of the class struggle and to act in accordance with forgetfulness, permit all this, keep such reformists in your ranks, and you will strike a blow at the heart of your movement.” (17)

De Leon’s opponents frequently charged him with intolerance and irreconcilability. But De Leon was by no means inclined to consider these qualities vices: “intolerance” and “irreconcilability” he regarded as necessary conditions to the success of the revolution, while “any action looking towards ‘lenience’ and ‘tolerance’ renders the revolution powerless.” (18)

De Leon assumed a definite position on the question of the party ownership of the press. Like Lenin, De Leon attached enormous agitational and organizational value to the press which he regarded as “the most potent weapon of the movement.” And since, the press, in his opinion, is not only a prerequisite, but also a product of the growth of the movement, requiring sacrifices in money, and long and great efforts, the party which has forged this powerful weapon must be confident that it will not be wrested from its hands and turned against it. De Leon therefore demanded vigilant control by the party over its press. (19)

The constitution of the Socialist Labor Party demanded that every member of the party should regularly subscribe to its organ, with the exception of those members who had no party organ in their own language. No member of the party and no local committee had the right to publish a newspaper without the sanction of the National Executive Committee of the Party. The latter controlled also the contents of all the party publications.

A different view was held by the Socialist Party, which even up to 1914 had no newspaper of its own. Only in that year was The American Socialist converted into the organ of the party, published by the Central Executive Committee in Chicago. At the same time the old rule, by which any member of the party or any local was entitled to publish his or its own press organ without the control or direction of the center, was preserved.

Autonomy or centralization? This question of inner-organization of the party also served as an object of differences between the Socialist Labor Party and the Socialist Party. While the latter allowed the State organizations autonomous rights, the constitution of the Socialist Labor Party, which was based upon the principle of centralism, gave to the National Executive Committee the power to expel any State Executive Committee.

De Leon explained the source of differences over this question as follows: The United States is a country nearly as large as all of Europe and does not constitute an economically uniform body. Capitalism has developed in every direction, but the country is so young that the primitive possibilities crop up at times even where capitalism has become deeply enrooted and, besides, the country is so vast that the primitive conditions still prevail over complete regions. Such a diversity of conditions, which testifies to different stages of economic development, inevitably breeds standards of spiritual development. A strong organization depends not only upon an identity of interests but also upon the degree to which these interests are developed.

“The proletarian elements which are closely tied up, by the navel string, to bourgeois interests cannot be as monolithic as the proletarian organization which has broken this navel string.” The non-proletarian elements which are attracted by both proletarian elements will, by virtue of the law of natural selection, acquire the characteristics which belong to the respective organization. “The less the revolutionary elements are developed in a class sense, the less homogeneous they are the less homogeneous they are, the weaker is their readiness to make sacrifices; the weaker their readiness to make sacrifices, the more scattered their efforts. On the contrary, the more class conscious the revolutionary elements, the greater is their homogeneity. The greater their homogeneity, the more actively are they prepared for sacrifices; the stronger their readiness for sacrifices, the more concentrated their efforts.”

The former represent the plain of the modern labor movement, and the class conscious elements its mountain. By virtue of its social nature the organization of the mountain elements conducts its work in a concentrated manner and naturally assumes a centralized form, while the elements of the plain move separately and their organization assumes the form of autonomy.” (20)

VII.

De Leon’s struggle against organizational opportunism was closely connected with his struggle against opportunism in the economic and political domains.

De Leon carried out a tremendous work in cleaning the Augean stables of the trade union movement in which opportunism flourished with particular gorgeousness.

At the beginning of 1898 the textile workers of New Bedford, Massachusetts, lost a long and bitterly fought strike conducted in the name of a number of immediate demands. On February 11, De Leon delivered in New Bedford an address entitled “What Means This Strike?” in which he attempted to explain to the workers “the principles of healthy organization” and “refute the theory that worker and capitalist are brothers.” Upon showing this with the aid of theoretical arguments, illustrated and backed up by figures taken from the workers’ own lives, De Leon scathingly ridiculed the comparison of labor and capital with the Siamese twins: wherever one went, the other followed; when one was happy, the pulse of the other was quickened; when one caught cold the other sneezed in unison with him; when one died the other followed him into the next world five minutes later…“Do you find,” De Leon asked the New Bedford textile workers, “that such are the relations between the workers and capitalists?’ Do you find that the fatter the capitalist becomes, the fatter does the worker become? Does not your experience tell you rather that the richer the capitalist the poorer the worker; that the more luxurious and magnificent the residence of the capitalist, the gloomier and humbler is the residence of the workers; that the happier the wife of the capitalist, and the greater his children’s opportunities for amusement and study, the heavier becomes the cross borne by the workers’ wives while their children are increasingly thrown out of the schools and deprived of the joys of childhood? Does your experience tell you this—yes or no?” “Yes, this is so!” came from every corner of the hall.

“The most important point underlying these facts,” De Leon continued, “is the fact that between the working class and the capitalist class there is an insuperable conflict, a class struggle for life. No haranguing politician is able to jump over it, no capitalist professor or official statistician to destroy it by arguments, no capitalist priest to conceal it, no labor faker to dodge it, no ‘reform’ architect to bridge it…”

And this struggle must end either in the complete subjection of the working class or in the destruction of the capitalist class. “You can thus see that the cry upon which your ‘pure and simple’ trade unions are based, and on the basis of which you went into this strike, is false. ‘There are no common interests, but there are antagonistic interests, between the capitalist class and the working class.” De Leon emphasized again and again. It is a hopeless struggle with the aid of which “healthy relations” are to be established between the irreconcilably antagonistic classes. (21)

Upon further exposing the secret of the primitive accumulation of capital and drawing a picture of the development of capitalism which leads to the replacement of skilled labor by machinery, the growth of the reserve labor army and the degradation of the standard of living of the bulk of the working class, and ridiculing the theory that the capitalists are the natural captains of industry, De Leon asked: Perhaps the capitalists are entitled to surplus value as inventors? But this, too, is a great mistake: the capitalists simply exploit the technical genius of others, using their distress and buying for a song the fruits of their hard mental labor. As a striking example of the acquisition by the capitalists of other people’s inventions, De Leon cited the case of the employees of the Bonsack Machine Company who were noted for their unusual inventiveness. Anxious to utilize their inventions without paying for them, the company locked out all of its men and then forced them to sign a contract by which all their future inventions would belong to the company. A certain worker invented as a result of six months of hard work, during which he did not receive a single cent from the company, a valuable machine for the production of cigarette cases. The worker himself patented his invention. But the federal court, before which the Bonsack Machine Company took up the case, issued an award in favor of the company.

This fact, as reported by De Leon, caused a storm of indignation in the hall. From all sides came the cries of “Shame! Shame!” De Leon then proceeded further to unfold his propagandist task.

“Shame?” he repeated the cries of the audience, “Shame? Do not say ‘shame’! He who sets fire to his own house has no right to shout ‘shame’ when the flames devour him. You better say: ‘This is as it should be,’ and, beating your breast: ‘It is your own fault!’ After electing into power the Democratic, Republican, Free Trade, Protectionist, Silver or Gold platform of the capitalist class, the working class can only blame itself if the official lackeys of this class turn against labor after gaining public power.” (22)

By this chain of arguments De Leon helped the audience to realize the basic “principle of healthy organization,” the fundamental elements of Marxism, which were astonishing revelations to the overwhelming majority of American workers.

These principles are as follows: Firstly, the workers will gain their freedom only after abolishing the capitalist system of private property and socializing the means of production. Secondly, the workers must wrest the power from the claws of the capitalist class. Thirdly, the workers must not regard politics as a private affair; politics, like economics, is the common business of all the workers. (23)

In this way De Leon educated the working masses with a view to freeing them from the influence of the opportunists.

De Leon attached tremendous importance to the trade unions. He saw in them not only an instrument of labor’s self-defense against the capitalist offensive, but also one of the most important and necessary instruments for the overthrow of the capitalist system. The labor movement, he maintained, is the lance which will strike down capitalism; the party is the sharp point of this lance, and the trade unions its shaft. Without the latter the lance cannot possess the necessary stability, without strong, class conscious and properly organized unions the party is useless. (24) Only in view of the existing backwardness of the trade union movement in the United States and its division, is the bourgeoisie able to resort to threats of a general lockout in order to bring pressure upon the working class voters, as was the case in 1896 when, with the aid of this method, the bourgeoisie forced the election to the presidency of its henchman McKinley, and forced the defeat, not even of a socialist, but of the radical Democrat, Bryan. The importance of class conscious industrial unions thus consists also in that they must establish, at the proper time, control over production and lock out the bourgeoisie. (25)

Some time around 1904—when De Leon’s peculiar system of ideas took final form De Leon began to regard the trade unions as the nuclei of the future society, as organizations which would take over the direction of the economic life of society after the revolution. (26)

But the trade unions will be able to solve both their immediate and historical problems only if they adopt different ideas and a different system of organization. The craft union, De Leon urged, appeared during the early days of capitalism and represented an unarmed hand which the workers instinctively raised to ward off the capitalist blows. Since then capitalism has grown to manhood, has changed its structure and become converted into a nationally and universally organized monopoly organism, while the trade unions continue in the same infantile condition and preserve their antiquated, archaic organizational form. They represent obsolete weapons, completely useless in the face of a modern navy. The craft union is like a pint which cannot hold three gallons of labor. (27) The trade unions must free themselves of their narrow craft egoism and reorganize themselves along industrial lines embracing all the workers in the given industry as well as those temporarily or permanently unemployed. The industrial union which connects up the economic struggle with the political struggle, the immediate aims with the historical objects, is “power, while the craft union is impotence.” (28)

“In the craft union movement only one section acts on the battlefield at one and the same time. By the fact that the other crafts idly look on, they betray those who do the fighting. In the craft union movement the class struggle is like a small riot in which the empty stomachs and bare arms of the workers fight against the well-fed and armed employers. (29) De Leon was fond of comparing the class conscious, industrially organized trade union movement with a fist, and the craft movement (by organization and ideology, the so-called “pure and simple” trade union movement) with spread out fingers fit only to serve as a fan to drive flies off the face of the capitalist class…

In the craft union movement De Leon saw the greatest obstacle to the victory of socialism. The bourgeoisie, he maintained, “strives to perpetuate the trade union movement in the antiquated form of craft unions as a powerful bulwark for the preservation of capitalism.” (30)

ORIGINALLY, De Leon supported the policy of boring from within. Thus, under his leadership, the party with the aid of the Jewish Labor Union which was under De Leon’s influence, captured ‘in 1894 the New York district organization of the Knights of Labor. At the Knights of Labor convention in the following year the radicals succeeded in defeating the reactionary leader of the Order, Powderley, who was opposed to a militant strike policy and supported peaceful cooperative development, but his place was taken by a certain Sovereign, who was a worthy successor of his reactionary predecessor.

In 1893 the United States was gripped by a serious economic crisis which shook the entire country. The number of unemployed reached the unprecedented figure of 6 million. The beginnings of the 90’s was marked by a series of big battles between the workers and trustified capital and at the same time by a number of disastrous defeats of the American working class. It is sufficient to mention the famous events in Homestead where the United States Steel Corporation with which the Carnegie Co. amalgamated, proclaimed war upon “The Amalgamated Union of Steel, Iron and Tin Workers.” The workers smashed up the forces of the detective and terroristic organizations which were hired by the trust to fight the trade union, but were themselves crushed by the superior forces of the special police. All of these events deeply stirred the American working masses.

In 1893 a group of socialists, headed by T. J. Morgan, made an attempt to utilize the situation for the organization of a mass labor party drawing its support, like the British Labor Party, from the trade unions. De Leon was skeptical of the success of this attempt. He did not believe in the possibility of converting the American Federation of Labor into an organization recognizing the principles of socialism. The result of Morgan’s policy was that many delegates of the A. F. of L. convention took a stand in favor of Morgan’s resolution, and even Gompers was instructed by his union to vote for this resolution. But the leaders of the A. F. of L. were determined at all cost to disrupt the attempt of the socialists to drive the trade unions to the path of the class struggle. Gompers himself voted against the resolution on the ground that the workers who favored it “did not know what they were doing.” The further policy of Gompers’ group consisted in gaining time in order to wade over the crisis and finally kill any attempt to create a class labor party. Gompers’ policy was crowned with success.

The outcome of the struggle between the socialists and the A. F. of L. leaders for the “soul” of the trade unions, as well as the abortive attempt to capture the order of the Knights of Labor, finally confirmed De Leon in his determination to wage an uncompromising fight upon the A. F. of L. and similar organizations. Beginning with 1895, De Leon definitely abandoned the policy of “boring from within,” that is of capturing the craft unions by working with them, and resolutely took up the path of dual unionism. “The trade union leaders,” De Leon used to say, “will let you bore from within only enough to throw you out through that hole bored by you.” At the end of 1895 the Socialist Labor Party, under De Leon’s leadership, organized a new trade union organization, the Socialist Trade and Labor Alliance, with a revolutionary socialist platform.

In the address already cited above, “What Means This Strike,” De Leon described the reasons for the creation of the Alliance as follows: “For a long time the Socialist Labor Party and the new trade unionists strove to convey this important message (“the healthy principles”) to the broad masses of American labor, to the rank and file of our working class. But we failed to make our way towards them, we could not get to them. We were divided by a solid wall of ignorant, stupid and corrupt labor fakers. Like people groping their way out of a dark room, we moved along the wall, banging our heads against it, constantly groping for the door in front of us; we made a circle but did not find a way out. It was a blind wall. Once we made this discovery there was nothing to be done but break a way through it. By the battering ram of the Socialist Trade and Labor Alliance we formed an exit; now the wall is crumbling, and we are finally standing face to face with the rank and file masses of the American working class and are conveying our message to them. You can judge this by the howl coming from that wall of fakers.” (31)

In the so-called “pure and simple” unions, that is in the unions which were organized along craft lines, De Leon refused to see a part of the labor movement. “The union which represents an enterprise of the ‘brotherhood of labor and capital’ represents a capitalist crew…Only a class conscious union is within the boundaries of the labor movement.” (32)

De Leon compared the craft labor movement with the Tsarist army. The craft union consists of workers, and the Tsarist army also consists of toilers; in both cases the decisive factor lies in the fact that these organizations are controlled by forces hostile to labor and serve interests hostile to labor. And just as in Russia the toilers cannot gain freedom without crushing the Tsarist army, just so in America will the working class fail to solve its problems unless it destroys the craft unions. (33)…In full, De Leon’s trade union policy was described by him as follows:

“This analysis shows that the trade unions as organizations are necessary. They are necessary in order to break the force of the capitalist attack, but this advantage of theirs is beneficial only to the extent that the organization prepares for the day of the final victory. ‘Hence every socialist must strive to organize his trade. If there is an organization in his trade which is not in the hands of a labor lieutenant of capital, he should join it and bring it into the ranks of the Socialist Trade and Labor Alliance. If the organization is completely in the hands of such a labor lieutenant of capital; if the members of the organization have become so closely identified with him and he with them that the one cannot be separated from the other; if, therefore, the organization, obedient to the spirit of capitalism, insists upon the division of the working class by more or less high barriers and intrigues against the admission of all members of the trade applying for admission; if the demobilizing influence of the labor lieutenant of capital is so strong as to make the majority of the membership of the organization approve and support his desire to maintain this majority at work by sacrificing the interests of the minority within the organization and of the immense majority of the workers of the given trade outside the organization—in this and in all other similar cases such an organization is not a part of the labor movement, it is a part of capitalism, it is a guild, it is… a belated reproduction of the guild system.” Such an organization, De Leon said, is no more of a labor organization than the Tsarist army. “In such a case a socialist must attempt to create a bonafide labor union and do everything within his power to destroy this fraud. (34)

It is characteristic that the policy of withdrawing from the reactionary trade unions for the purpose of creating class conscious industrial organizations was supported not only by the Socialist Labor Party but also by the left wing of the Socialist Party, including Eugene Debs, one of the most popular leaders of the American workers. (35)

The peculiar conditions of the American labor movement— the fact that the tremendous majority of the workers are unorganized, the artificial measures taken by the reactionary leaders to perpetuate this scourge of the American labor—in some cases make inevitable the policy of dual unionism. The policy of unity at all cost cannot, under the American conditions, always yield favorable results (of course, from the point of view of the revolutionary proletariat). We know that in recent years the development of the labor movement in the United States inevitably led to the formation of new unions (of needle trades workers, furriers, textile workers, miners) which broke with the A. F. of L. and joined the Profintern. At the beginning of September of this year (36) a national convention was held in the United States which created a new trade union centre to lead those organizations which adhere to the platform of the class struggle. Thus, life forced the advanced workers of America to consolidate their forces on a new foundation.

The main weakness of De Leon’s policy consisted of its sectarian extremes, exaggerations and intolerance. Was it not meaningless for the S.L.P. to adopt in 1900 a resolution forbidding members of the party to hold leading offices in the craft unions and admit into the party officials of such unions? Is it not the duty of the party, on the contrary, to utilize the capture by its individual members of leading positions in the trade unions for the purpose of directing these organizations along the proper path?

This sectarian attitude of De Leon which caused the revolutionary labor movement of the United States a good deal of harm, was due to the fact that he overestimated the immediate revolutionary possibilities in the United States. It is the fate of many revolutionists to see the much desired goal much nearer than it is in reality. De Leon looked upon the historical prospects of America through field glasses. In 1893 Debs created the industrial American Railroad Union which soon embraced 150,000 workers. In that same year was organized the Western Federation of Miners which adopted a socialist platform. In 1897 the Western Federation of Miners withdrew from the American Federation of Labor. True, during that year the American Labor Union fell under the powerful blows of the capitalist offensive; true, by 1905 the Socialist Trade and Labor Alliance had only 1,400 members, but, to offset this, the Industrial Workers of the World were organized as a mass labor organization, the role of which in the organization of the revolutionary elements of American labor must not be underestimated. These facts confirmed De Leon in his belief in the possibility of the speedy capture of the majority of American labor on behalf of revolutionary socialism. But the road towards this coveted object proved to be much more difficult and devious than De Leon thought. In the next article I will show that the great American revolutionist learned the lesson of the movement and in 1908 adopted a more sober and flexible position on tactical problems, though even then he did not completely free himself from the elements of sectarianism.

VIII.

De Leon’s greatest merit was his consistent and uncompromising struggle against parliamentary cretinism.

Does not “a political visionary” deserve contempt who imagines that upon going to the ballot box and throwing into it a piece of paper he can rub hands with delight and wait with satisfaction that thanks to this process, as if by some alchemical trick, the election will put an end to capitalism and that from the ballot box the socialist society will arise like a fairy, De Leon said. (37)

The most important task of revolutionary socialism De Leon saw in the destruction of the “mystic labyrinth which Marx called the cretinism (idiocy) of bourgeois parliamentarism.” (38)

This does not mean that De Leon denied the necessity of utilizing the bourgeois Parliament. He merely pointed out that, inasmuch as the socialist vote is a question of right, unless it is based upon power, it

…is weaker than women’s tears, Gentler than dream, madder than ignorance, Even less brave than a maiden at night, And artless as inexperienced childhood… (39)

In parliamentarism De Leon saw primarily an instrument of revolutionary propaganda. (40) But in order that the parliamentary activity of the socialists could perform this function it must be “uncompromisingly revolutionary.”

W. Liebknecht’s aphorism, “To participate in Parliament is to resort to compromises,’ De Leon considered admissible only under the conditions of a bourgeois revolution, but such a policy is marked with the “brand of treason to the working class” when applied in modern America. (41)

De Leon hated with a deadly hatred the opportunists from the Socialist Party who, in the chase for votes, supported the A. F. of L. in its struggle against the colored workers, proclaimed its neutrality towards the reactionary trade union leaders, entered into unprincipled blocs with capitalists of the type of Hearst (the newspaper magnate), etc., and hopelessly sank in the mire of political and other reforms. “All such ‘improvements,” De Leon said, “like the modern ‘election reform,’ the schemes of ‘referendums,’ ‘initiative,’ ‘election of federal senators by a national vote,’ etc., are by their very nature bait intended to dampen revolutionary enthusiasm.” The task of the proletariat consists of socializing the means of production without which “the cross which it now bears will be even heavier and will weigh down the next generations with even greater force. No ‘reform’ can take its place.’ (42)

In 1922 an event occurred in the political life of the United States which strongly corroborated De Leon’s view of reformism as an instrument for the deceit of the working class. The former President Theodore Roosevelt quarreled with the Republican Party bosses who nominated Taft, Roosevelt’s rival, as candidate for the Presidency, and decided to run for election without the support of the Republican Party, hoping to attract the masses of discontented workers and farmers. For this purpose he advanced an election platform which was completely copied from the Socialist Party and secured more than 4 million votes. One of the leaders of the Socialist Party, Victor L. Berger, kept on complaining that Roosevelt robbed the Socialist Party… (43) One naturally recalls De Leon’s reference to the reformist platform as the skin of a banana which will cause the reformist to slip himself and bring down the proletariat with him.

In close logical connection with De Leon’s struggle against parliamentary cretinism stands his struggle against respect for capitalist laws. In September, 1912, “The Visitor,” a weekly organ of a certain ultra-montanist organization in Rhode Island, published 15 questions which, in the opinion of its editors, were to put socialism to shame in the eyes of every respectable citizen. Among these questions, which the editors recommended the readers to cut out and always carry with them, one related to confiscations. Do not the socialists, “The Visitor” asked, intend to confiscate capital? De Leon at once gave a comprehensive reply in the “Daily People.” (44) To him this question was neither new nor unexpected. He had given the answer to it on April 14, 1912, in a debate in the city of Troy on the question of “Individualism versus Socialism,” and ten years earlier, in 1902, in “Two Pages from Roman History.”

The proletarian revolution, De Leon replied, strives to socialize all the means of production. This act will be a crime from the point of view of capitalist laws and conceptions, but every revolution carries with it its own code of laws. From the point of view of the British, Jefferson, the leader of the anti-British revolution, for national independence, was a “confiscator,” for, contrary to the British laws, he wrested the American colonies from England’s hands, but from the point of view of the American people, including the bourgeoisie, Jefferson was a national hero who proved to be able to ignore the laws of the oppressor and establish new laws corresponding to the interests of the liberated people. The bourgeoisie itself, when acting as a revolutionary class, pointed out to the proletariat the way to the solution of its historical class tasks. The bourgeois legality does not in any way permit the proletarian revolution. The latter carries within its womb its own statute. “A revolutionist who seeks a toga of ‘legality’ is a defunct revolutionist; he is a boy playing at soldiers… (45)

As a striking example of the helplessness of a socialist who has not learned to take a dialectical view of the problem of law and who does not dare honestly and openly to explain it to the workers, De Leon referred to the case of Thomas J. Morgan, whom we have already mentioned in connection with the attempt to organize a labor party. In 1894, while addressing the American Federation of Labor convention in Delaware with a vehement appeal in the name of Socialism, Morgan was interrupted by one of the leaders of the Federation, Adolf Strasser,

“Can I ask you a question?”

“Of course.”

“Do you approve of confiscation?”

…And Morgan fizzled out like a bubble. Strasser felt that he gave the socialist agitator a knock-out blow.

IX.

De Leon was an internationalist. (46) The sharp weapon of his criticism he directed not only against the native opportunism but also against its manifestation in the international labor movement. De Leon belonged to the consistent left wing of the Second International. (47) He was one of the first to raise arms against Kautsky and expose his opportunism when Kautsky was still at the zenith of his revolutionary fame.

De Leon took up and popularized the apt description of Kautsky’s Paris resolution (1900) on the Millerand case, as a “rubber resolution.” At the Amsterdam Congress, De Leon delivered a sharp attack upon Kautsky and demanded a revision of the Paris resolution. Here is the resolution which De Leon submitted in the name of the Socialist Labor Parties of the United States, Australia and Canada:

“WHEREAS,

“The struggle between the working class and the capitalist class represents a constant and inevitable conflict which will grow sharper rather than weaker with every day;

“The existing Governments represent committees of the ruling class assigned to preserve the yoke of capitalist exploitation upon the neck of the working class;

“At the last congress in Paris in 1900 a resolution was adopted, known as the Kautsky resolution, the last paragraphs of which permit in some cases the representatives of the working class to accept State offices from the hands of capitalist governments, and particularly provide for the possibility of impartiality on the part of the governments of the ruling class in the conflicts between the working class and the class of capitalists, and,

“The above paragraphs—perhaps applicable to countries which have not yet completely freed themselves of feudal institutions— were adopted under the conditions both of France and of the Paris Congress which may justify the mistaken conclusions of the nature of the class struggle, of the character of the capitalist governments and of the policy which the proletariat must follow in its anxiety to abolish the capitalist system in countries which, like the United States of America, are completely free from feudal institutions—this congress resolves:

“Firstly, that Kautsky’s resolution referred to is rejected as a principle of general socialist policy.

“Secondly, that in countries, like America, which are fully developed from a capitalist point of view, the working class cannot, without betraying the proletarian cause, accept any office which it does not conquer for itself.” (48)

It is noteworthy that if De Leon very conditionally (perhaps) admits of the possibility of applying Kautsky’s policy in countries which have not yet been freed from the elements of feudalism and which were therefore, as De Leon thought, still unripe for the socialist revolution, for the Anglo-Saxon countries, and primarily for the United States, where, according to De Leon, after the civil war of 1861-1865, the working class and the capitalist class faced each other as enemies, De Leon insisted upon an uncompromising revolutionary policy which is at the present time formulated as the policy of “class against class.”

The relations between De Leon and the leaders of the Second International, particularly Kautsky, were cool and strained. According to Boris Reinstein, a former member of the Central Committee of the Socialist Labor Party and De Leon’s right hand man, the latter went without enthusiasm to the Congress of the Second International where the S.L.P. delegations were practically ignored and the Hillquits and Simonses felt in their own element. The situation in America and the struggle between the two socialist parties of the United States were judged by the malicious speeches of the Socialist Party representatives at the congress and in the leading European socialist journals, particularly the “Neue Zeit,’ where De Leon was painted as an anarchist and a wrecker of the trade unions.

De Leon was inclined to explain the coolness of the leaders of the International towards the Socialist Labor Party by the difference between the social and economic structure of the United States and of the European countries. “They cannot understand us,” De Leon maintained, “we are divided from them not only by a physical but also by an historical ocean. They still live under semi-feudal conditions while we are at the threshold of the socialist revolution.” We will not criticize here De Leon’s mistake which consisted of his failure to understand the possibility of the socialist revolution breaking out first in a country with a “relatively smaller development of industry.”(49) To us one thing is unquestionable, the cool attitude of the leaders of the Second International toward De Leon’s Socialist Labor Party sprang from the same sources which were responsible for the coolness toward the Russian Bolsheviks, the Bulgarian “Tesniaks,” the Dutch “Tribunists,” in short towards the revolutionary wing of the international labor movement.

X.

Up to 1918 Lenin was apparently unacquainted with the works and views of De Leon. At the Stuttgart congress to which both De Leon and Lenin were delegates, they worked in different commissions (the former in the trade union commission) and did not meet in their work.

In 1918 an article was published in the “Workers’ Dreadnought” entitled “Marx, De Leon and Lenin.” The article was signed by Margaret White, the pseudonym of a prominent British Communist. The author of the article expressed the belief that De Leon was Lenin’s predecessor in anticipating the Soviet system. (50) Lenin then became greatly interested in the American revolutionist and asked B. Reinstein to bring him De Leon’s works which Lenin studied only at the end of 1918, after recovering from his wound.

On May 11th, 1918, the “Weekly People,” the organ of the Socialist Labor Party, published an address by John Reed, of which the following is an excerpt: “Premier Lenin,” Reed said, “is a great admirer of De Leon, whom he regarded as the greatest of modern socialists, the only one who added something new to socialist thought after Marx. Reinstein took with him to Russia several pamphlets written by De Leon, but Lenin wanted more of them. He asked Reed to send him several copies of all the published works of Le Leon as well as a copy of “With De Leon since ‘89’,” a biography written by Rudolph Katz…Lenin intended to have them translated into Russian and write the preface to them.” (51)

In a private conversation B. Reinstein told me that at the end of May, 1919, he spoke with Lenin about De Leon.

“But did not De Leon err on the side of “sectarianism?” Lenin asked half jestingly, half earnestly, but added that he was mightily impressed by the sharp and deep criticism of reformism given by De Leon in his “Two Pages from Roman History,”

as well as by the fact that as far back as April, 1904, De Leon anticipated such an essential element of the Soviet system as the abolition of Parliament and its replacement by representatives from production units.

Of course this is not the Soviet system but only an element of the Soviet system. From the Bolsheviks De Leon was divided by his failure to understand the inevitability and necessity of a transitional epoch in the form of a dictatorship of the proletariat. He believed that the socialist revolution would at once eliminate the State, and that society would step right into developed socialism on the morrow of the revolution. This explains De Leon’s denial of the need for a party, after the revolution. We can thus see that no equation mark can be drawn between De Leon and Bolshevism. However, there is one thing which unquestionably makes them akin to each other, namely, the uncompromising and determined opposition to opportunism in all its forms and manifestations.

De Leon died on May 11, 1914, that is before the world war and the Russian Revolution. We have every reason to believe that the great American Revolutionist would have learned the lessons of these historical events and supported the position of Leninism. In any case, De Leon’s unquestionable merit consists in that in a number of Anglo-Saxon countries he trained cadres of revolutionary Marxists who are now struggling within the ranks of the Communist International. (52)

NOTES

1. Translated from Problems of Marxism, Volume 2.

2. John Mitchell, Organized Labor, Philadelphia, 1903.

3. American Federationist, July, 1906.

4. Samuel Gompers, Labor and the Employer, New York, page 33.

5. By International Unions are meant unions embracing the workers of the United States and Canada.

6. American Federationist, January, 1900.

7. Samuel Gompers, Labor and the Employer, pp. 45-48.

8. See De Leon’s Flashlights of the Amsterdam Congress, page 95 (De Leon Resolution at the Amsterdam Congress); “The Intellectual,” (Daily People, March 19, 1905); “Haywoodism and Industrialism,” (Daily People, April 13, 1913); etc.

9. Daniel De Leon, The Burning Question of Trade Unionism, New York, page 30.

10. Ibid. Reform or Revolution, New York, 1924, pp. 22-23.

11. Ibid. page 30.

12. De Leon, Two Pages from Roman History, New York, 1902, p. 81.

13. Ibid. pp. 82-83.

14. Morris Hilquitt, The History of Socialism in the United States, p. 239. (Russian translation.)

15. Reform or Revolution, pp. 16-18.

16. The Burning Question of Trade Unionism, p. 41.

17. Reform or Revolution, p. 24.

18. Two Pages from Roman History, p. 72.

19. Unity, an address delivered by Daniel De Leon, Feb. 21, 1908. New York, 1914. pp. 13-14.

20. Unity, pp. 15, 16 and 18.

21. Daniel De Leon, “What Means This Strike?” New York, 1926. pp. 13-14.

22. Daniel De Leon, “What Means This Strike?” p. 19.

23. Ibid., p. 30.

24. The Burning Question of Trade Unionism, pp. 30-31.

25. Daniel De Leon, Socialist Reconstruction of Society, New York, 1925. p. 43.

26. This conception was stated by De Leon in its fullest form in his Preamble of the Industrial Workers of the World (1905). Since 1918 this work was published under the name of Socialist Reconstruction of Society.

27. The Burning Question of Trade Unionism, pp. 21-25.

28. Socialist Reconstruction of Society, p. 46.

29. Ibid.

30. Unity, p. 20.

31. “What means this Strike.” p. 31. According to the constitution of the Socialist Alliance its officials had to give a written pledge a8 follows: “I consider it the sacred duty of every toiler, especially of those who have been entrusted by their fellow workers with a special mission of office in the class struggle, to break all, direct or indirect, connections with the political parties of the capitalist class. I pledge my word of honor that I will obey the constitution, rules and decisions of the Socialist Trade and Labor Alliance of the United States and Canada and, always remembering its fundamental principles and ultimate objects, will fulfill my task to the extent of my abilities.” (See “Socialism versus Anarchism,” by Daniel DeLeon, New York, 1921, p. 32.)

32. Daily People,” March 19, 1905. “The Intellectuals.”

33. The Burning Question of Trade Unions,” p. 34.

34. Ibid. pp. 33-34.

35. Debs: “There is only one way of effecting this great change, and it consists of the worker breaking with the American Federation of Labor and joining a union which intends to represent the interests of his class in the economic field.” (“Proceedings of the First Convention of the Industrial Workers of the World,” New York, 1905, p. 143.)

36. 1929.

37. “Proceedings of the First Convention of the IWW,” p. 228.

38. Daily People,” of August 8, 1909.

39. Socialist Reconstruction of Society,” p. 40.

40. See his article “Haywoodism and Industrialism,” in the “Daily People” of April 13, 1913.

41. “Socialist Reconstruction of Society,” p. 41.

42. “Two Pages from Roman History,” pp. 70-71.

43. “Here is what Lenin wrote about the result of the 1912 elections: “Lastly, the importance of the election lies in the unusually clear and striking manifestation of bourgeois reformism as a means of struggle against socialism….Roosevelt has been obviously hired by the clever millionaires to preach this fraud.” (Lenin’s Works, 1925, Vol. 12, Part 1, pp. 323-324).

44. “Daniel De Leon “Fifteen Questions,” 6th edition, New York, 1925.

45. “Two Pages from Roman History,” pp. 73-74. “Fifteen Question,” pp. 84-85, 88.

46. In 1911 De Leon sharply took to task the only socialist congressman, Victor Berger, for failing to make use of the congressional platform for the international education of the workers. In the opinion of De Leon, Berger should have made an international demonstration during the election of the Speaker at the first meeting of the congress, by nominating its own candidature in the name of “The American Branch of the International Socialist Family.” (See “Berger’s Hits and Misses,” by Daniel De Leon, New York, 1919).

47. De Leon attended the following congress of the Second International, the Congress of Zurich (1893), Amsterdam (1904), Stuttgart (1907), and Copenhagen (1910).

48. “Flashlights of the Amsterdam Congress,” pp. 94-95.

49. See A. Angorov “De Leon and Lenin on the Question of the Proletarian State,” “Revolutsia Prava,” 1927, No. 4.

50. The same idea was expressed by the author in his book “Communism and Society,” by W. Paul, 1922.

51. Quoted from Olive M. Johnson’s “Daniel De Leon, Our Comrade,” which was published in the Symposium “Daniel De Leon, The Man and his work,” I. p. 81, New York, 1926. Lenin’s great interest in De Leon was noted also by Robert Minor (“The World,” February 4, 1919 and Arthur Ransome (“Russia in 1919,” by Arthur Ransome.) According to B. Reinstein, in May, 1919, Lenin intended to write an article devoted to the Fifth Anniversary of De Leon’s death, but some circumstances prevented him from carrying out his intentions.

52. Thus MacManus, Murphy, Tom Bell, William Paul and other leaders of the British Communist Party are pupils and former disciples of De Leon.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This ‘Communist’ was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March ,1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of issue 1: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v09n09-sep-1930-communist.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v09n10-oct-1930-communist-mop-up.pdf