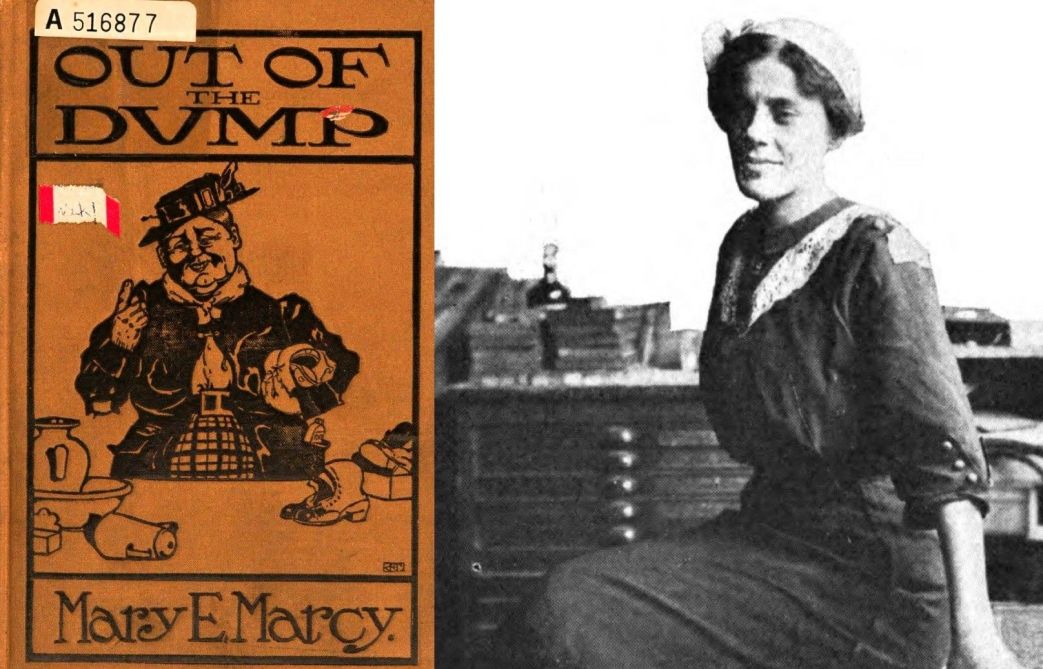

The third chapter of Mary Marcy’s first book, ‘Out of the Dump: A Story of Organized Charity,’ illustrated by Ralph Chaplin and originally serialized in the International Socialist Review. Telling of an orphaned girl of the working class having to navigate Chicago’s charity system to survive, the story is close to Mary’s own. While still a teen she lost both of her parents becoming the primary care-giver for her two younger siblings, Hazel and Roscoe, as they were shuttled between family and ended up in Chicago with Mary working as a telephone operator. Later in life, after being fired as a whistle blower from the pork-packing industry, she worked for Kansas City charities, which she would be severely critical of and also certainly informed this story.

‘Chapter III: The Wineshevskys’ by Mary E. Marcy from Out of the Dump. Charles H. Kerr Co-Operative, Chicago, 1908.

I HOPPED OFF THE CAR at Wilson street one very warm Saturday afternoon in June. In my hand I carried a bag of big purple plums for Sammie and the baby and in my pocket a pair of Mrs. Von Kleeck’s cast-off side-combs for mother. I was very happy, for there had been great doings at the big house and mother was just the one to let me sit on the rocking-chair while she listened to everything I told, from the price Mollie, the china-closet maid, paid for her slippers, to the number of dishes Mrs. Van served at her last little dinner.

I believe mother sometimes fancied I stretched things, but I didn’t. Children who grow up thinking in pennies are not likely to guess too high about people like the Van Kleecks.

As I turned the corner I saw Sally Higgens and all the other Higgenses and Mrs. Wineshevsky and the Schmidts holding a confab on the steps leading to “our basement”. As I drew nearer I saw a big sign over the stairway. Small Pox, it said. And Mrs. Wineshevsky came to meet me and told me all about it.

Mother had found a job at the Glue Works. Every morning she had left Sammie and the baby at the Day Nursery at 6:30 and had called for them at 7:00 in the evening. That morning six of the children at the Nursery were so ill that the Matron called in the City Physician. He pronounced the trouble to be small pox and by one o’clock the afflicted children were all removed to the Pest House. Sammie and the baby were among them.

The Glue Works close at one o’clock on Saturdays and a short time later mother discovered the children had been taken away. Mrs. Wineshevsky said mother didn’t stop for anything but hurried out to the old hospital built way up in a bend in the river to keep the disease from spreading to “the better portion of the population.” They were glad to have mother come to take care of the children, because the only attendants at the Pest House were a man and his wife, both too old and worn-out to be able to do much for anybody except themselves.

Mrs. Wineshevsky said there seemed to be a regular epidemic of small pox at the Dump. I was very much disappointed. It seemed too bad to carry the plums all the way from the boulevard for nothing. I was not much frightened, because people were always having small pox in the Alley or at the Dump. Daddy and mother had had it years before, so I went over to Schmidt’s and took the plums to Mamie. I thought I’d have a little holiday anyway.

It happened to be the day of the meeting of the Trustees for the Society-for-Securing-Employment-for-Protestant-Women-With-Infants-Under-One-Year-of-Age. And the meeting was held at the home of Mrs. Van Kleeck, Jr. Holding meetings at Mrs. Van’s was the only sure way of getting her to attend them. But when people want anybody badly enough, they are willing to go to them. They were always going to Mrs. Van Kleeck.

Mrs. Van had been made President of the Society-for-Sepuring-Employment-for-Protestant-Women-With-Infants-Underone-Year-of-Age, because the Society needed the advertising. They told her she wouldn’t need to do anything but be president.

Mrs. Kensington happened to inform Mrs. Van Kleeck about the epidemic at the Dump. And inside of an hour I was marched into our room in the basement by the Health Officer and told to stay there.

It seems Mrs. Van Kleeck was afraid of infection. The City Physician said there seemed to be nothing the matter with me, but I would have to stay away from Mrs. Van’s for nine days till he could be sure, and then, after I was thoroughly fumigated, disinfected and sterilized, perhaps I should be allowed to return.

It seemed pretty hard lines for me, because after being shut up in the basement I was more than likely to contract the small pox myself. But as soon as the Health Officer had gone, I sneaked out and went over to tell Mrs. Wineshevsky about it. She took me in. She was the kind of a woman that always takes everybody in. It would have been fun being with her for a change if everybody hadn’t been sick except Mrs. Wineshevsky. Zeb and Lucy were down with typhoid fever and little Anna was so ill she didn’t know us. I helped with the work, as Mrs. Wineshevsky sorted rags all day at an old second-hand shop and Mr. Wineshevsky worked for a carpenter in the Alley, on his “good days”. He had queer brown patches all over his face and neck and looked sick always.

Mrs. Wineshevsky was a very nice woman. She was always working as fast as she could make her fingers fly. It seemed to me that she just bustled through life and kept things moving somehow for the whole family.

There was great fear in her eyes when she came home from work in the evening, fear that the children would be worse. She would steal gently up to little Anna who lay most of the time in a heavy sleep, and put her hand softly upon her head. Young as I was, it made my heart ache for I knew she was afraid that sometime her little one would not awake.

Miss Crane, who was one of the Nurses from the Visiting Nurses’ Assn., came to see the children. She was a pleasant woman. She wanted to make everybody clean and well and to have happiness and the sun shining over everybody all the time. I think she believed that if poor people would only choose work in the fresh air, sanitary houses to live in, if they would eat pure wholesome food and wear healthful clothing, everything would be all right in the poor man’s world. She found out what was the matter at the Wineshevskys very soon.

There was a queer ‘smell about the house. Miss Crane began to poke her nose around to find out where it came from. By and by she pulled up a loose board in the kitchen floor and looked through. The whole cellar was filled with a dark and sickening fluid. There was no drainage, nor sewerage and never had been any.

She explained to them all about it.

“There’s no sewerage here,” she said; “and you will have to move out of this house at once, or the children will die. Before you know it, you will be ill yourself, Mr. Wineshevsky. Nobody can live among the germs that come from that poison without getting sick.” Then she bathed the three children and went away.

Every time she came she told them the same thing and every time she spoke more strongly. She knew nobody could ever get well among the mob of microbes that inhabited that house. She said she could smell them coming through the floor in hordes.

Mr. Wineshevsky thought over Miss Crane’s words every day. He had read in the papers that the Hon. D.C. Peters, who was trying to force the City Administration to give him a new street car franchise, owned many “death traps” and “undrained hovels” on Wilson Street. He had learned it from the papers, that were trying to beat Mr. Peters, and he thought he saw a way out of the difficulty.

He talked the matter over with Mrs. Wineshevsky and she agreed with him. It was impossible to move into another house while the children were sick. It seemed there was nothing else to be done and no time to lose, for Anna grew every day a little weaker.

And so, on his next “good day” Odin Wineshevsky, armed with his own despair, went to the city to find Mr. Peters. I am not sure that he knew just? what he expected Mr. Peters to do.

“I’ll make him put in a sewer or save the children in some way. I will not come back till I find him and bring help,” he told Mrs. Wineshevsky. He was gone three days.

It was a bad time for the family at home. Mrs. Wineshevsky worked and cried. Occasionally she hoped a little. I have seen that mothers (I mean those who are the wives of poor men) never despair as long as there is work to be done. But the children were slowly burning away with the terrible fever, and Mrs. Wineshevsky saw them fading before her eyes.

Perhaps it was almost as hard for Odin Wineshevsky away in the city seeking help. For an endless day he watched outside of the Peters palace on the boulevard, till the servants thought he was crazy and threatened to call the police. But he followed Peters to the Club. There he was refused admittance. It is surprising that he was not arrested and thrown into jail for he was pale and worn and badly dressed. And rich and happy folks are strangely fearful of the despairing and miserable poor.

But Odin Wineshevsky waited his time. He was not too insistent. From early in the evening till long past midnight he watched in the rain while the great man dined at a banquet. He grew faint from standing outside the great office building of the Peters Real Estate Company, scanning each face that emerged from the doors. By this time he would have been able to recognize Peters. He even fell asleep on the stairs of the office building. He had no money but someway he managed to live through.

Doubtless he begged a little, or they fed him at the saloons. On the third morning as he waited near the general office of the Telephone Company, Mr. Peters accompanied by a reporter on one of the opposition papers, came out of the door. And Odin Wineshevsky heard his Opportunity.

He told his story briefly in a voice that trembled with misery and despair and when he talked of the slime and sewerage running under the house, and the advice of the Visiting Nurse, his tones grew bolder and his words rang through the hall of the great building. Immediately a little crowd began to gather around the elevator.

Mr. Peters seemed touched by the story. He said he had no interests whatever in the stockyards district, but that it would give him a great deal of pleasure to see that the little ones were cared for.

And while Odin Wineshevsky leaned weakly and tearfully against the wall (now that the crisis was past) Mr. Peters returned to his office where he called up the B— Hospital asking them to “fix it up and send down for the little Wineshevsky girl” as soon as it was possible to do so.

Mr. Wineshevsky wept when he tried to thank Mr. Peters before he went back to the Dump, and there were real tears in Mr. Peters’ eyes. If there was one thing Mr. Peters hated above all others, it was folks blessed with wealth who have no time to extend the hand of sympathy to men like poor Wineshevsky.

He said this to the reporter (for the opposition paper). Besides he had promised to pay for the support of a charity bed at the B— Hospital for one year and he thought he might as well make use of it.

Mrs. Wineshevsky was having a bad time of it. Zeb and Lucy were worse and Miss Crane said Anna’s fever was higher. I helped all I could, bathing the children and using the ice Miss Crane had sent. Most of the time they lay in a heavy stupor. It was almost like a funeral.

Mrs. Wineshevsky was ill too, but on the third day, she also went to the city—this time to see the City Physician. He promised to come in the afternoon to see what could be done for the children.

At four o’clock that day little Anna died. A little later the ambulance from the B— Hospital arrived and Mrs. Wineshevsky persuaded them to take Lucy away instead. It seemed doubtful if she could live.

Two days later the City Physician called. He left some medicine and told Mrs. Wineshevsky there was no use doing anything till the family got out of that house. A day or two later Zeb died and Lucy never recovered in spite of the care that was spent upon her at the hospital.

The family—what there was left of it—never rallied from the blow of the death of the three children. Odin dribbled along more painfully and aimlessly than he had ever done on his “worst days”. And Mrs. Wineshevsky turned into a bundle of hate that seemed to include even her old friends and neighbors at the Dump.

One day Mr. Wineshevsky wandered away In one of his foolish spells and Mrs. Wineshevsky grew more bitter than before.

When I went to work in the office of one of the Charity Bureaus, I happened to run across the record of the Wineshevsky family. It reads something like this:

Wineshevsky, Odin and Annie (Polish) aged 32 and 27 years. Three children, Zeb 8, Lucy 6, Anna 3. (Three children dead). Living at 326 Wilson street; 3 rooms; rent $10.00; say they wish to rent front room. Mrs. W. working at 54 Arch street, sorting rags; wages $7.00. Mr. W. works little; claims he is sick; believe he is lazy. Family ought not need help. House untidy. Seem to be shiftless and poor managers. Visiting Nurse found three children sick; typhoid fever; told family to move, but seemed too ignorant and stubborn; no sewerage in house.

Mr. D.C. Peters, President of the B— Hospital and the Street Railway Co., became interested in case and had Lucy sent to hospital. June 4, Anna died; found Mr. and Mrs. both home. Neither working. Advised Mr. W. to go to work. June 10th. Zeb died. June 15th. Mrs. W. ordered Friendly Visitor out of house. Has a violent temper. June 21st. Lucy died at B— Hospital. Dec 27th. Odin W. was sent to Hospital for the Insane.

All this happened seven years ago. Families have continued to live and to die in the Wineshevsky house at 236 Wilson street. There’s a new family there now of the name of Friedman. The sewerage continues to slumber as peacefully as of old under the bed room and the kitchen and I suppose the microbes continue to riot and to romp in the same old way, for little children continue to droop and to die there. The Hon. D.C. Peters still owns the place and still sheds the halo of his prestige around the B— Hospital. His name graces the stationery of that institution as of old. He has not ceased to dispense charity with his right hand (from the spoils he has taken with his left). And it is all a very terrible farce.

My brother Bob says we can’t expect him to be any different. He says we can’t expect anybody to be different, but he’s hoping some day the working people will. He says if they owned the factories collectively and paid themselves the value of the things they make, instead of giving the profit or rake-off to the boss, they’d be able to have beautiful homes themselves, wholesome places to live in, where the little children would have the best chance in the world for their lives.

It makes Bob hot when people who work have to go around asking for favors. He says they ought to stop “dividing up” the wealth they produce. He wants them to be the rulers of the world and keep it themselves. He says, if he had half a chance, he’d go to work himself, but he can’t bear to plug along just to enable the boss’s wife and daughters to wear diamonds.

Charles H Kerr publishing house was responsible for some of the earliest translations and editions of Marx, Engels, and other leaders of the socialist movement in the United States. Publisher of the Socialist Party aligned International Socialist Review, the Charles H Kerr Co. was an exponent of the Party’s left wing and the most important left publisher of the pre-Communist US workers movement. It remains a left wing publisher today.

PDF of full book: https://archive.org/download/InternationalSocialistReview1900Vol08/ISR-volume08_text.pdf