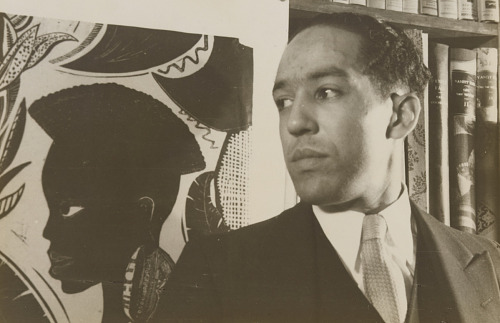

Biographical vignettes of cities–Kansas City, Chicago, Mexico City, New York, and Paris–visited by Hughes at different ages. Raised in Lawrence, Kansas and Midwestern cities, this prize-winning essay from 25-year-old Langston Hughes was written after returning to the U.S. following his work as a merchant marine and extensive travels through the Americas, Africa, and Europe.

‘The Fascination of Cities’ by Langston Hughes from The Crisis. Vol. 31 No. 3. January, 1926.

Second Prize Essay in THE CRISIS Contest 1925

Mr. Hughes won the third prize in poetry and the second prize in essays in our contest. His biography and portrait appeared last month. Knopf will print his first volume of poems, “The Weary Blues”, this month.

The First City

DAWN is sodden, grey. The stubble of wheat fields, the hills and bluffs of the Kansas River. The clack, clack, clack of the train running between long lines of freight cars, the railroad yards. “Union Station!” “Kansas City!”

The bellowing voice of the brakesman, a jar and a curve, houses high on a bluff, a tiny street car running way up there. The old station in the bottoms. Hustle, hurry. “Cab, mom, cab?”–This way to the street cars “Bus to your hotel! Take your baggage!” Mother holds me tightly by the hand. I am five years old. I am in the city for the first time.

I remember well. Night. My uncle’s house. Spare ribs and corn and sweet potatoes and a can of beer. A gala occasion. The Williams and Walker company in town. The greatest colored show in the world is in town.

“O Bon Bon Buddie,

“My chocolate drop,

“My chocolate drop

“Dat’s me!”

George Walker, the beautiful brown girls, the crowded theatre, the applause, the laughter. I am five years old. The cool night air, the autos, the streets, the lights, the people affect me. “Look, mother! Oh, mother, look!” The fascination of cities seizes me, burning like a fever in the blood. “I don’t want to leave this city, mamma. When I get to be a big man, I am going to live forever in this city!”

Chicago

I am fourteen. I work in a hat store in the loop. The crush of the city is all about me. The vast, ugly, brutal, monotonous city, checker-boarded, hard. The L trains circle in a crazy loop. The L trains rattle and roar behind Wabash Avenue, shaking the houses, houses, houses on Wabash Avenue. The tiny second-story room I sleep in has a window opening onto the tracks of the L trains. The red and green lights of the passing cars whiz and flash in my sleep, dreams. The approaching dull rumble, the loud rattle and roar fading to the dying dull rumble, punctuate my hours of sleep. I take long rides on the L trains, Evanston, Oak Park, Englewood. I cover the monotonous miles of Chicago delivering hats. On Sundays I walk on State Street–glittering Broadway of the Black Belt. Lighted theatre fronts. The Whitman Sisters at the Grand. The first colored movie ever shown. Street stands. “Sweet water-million right here!” The fish sandwich man. The girls with too much powder, beckoning eyes, red, red lips. “You love me, don’t you, honey!” “Ah, Cora, leave him alone. He’s only a kid.” Crap games in the vacant lots. “Cheese it, the cop!” The medicine man, the corner preacher. The dark, throbbing life of the streets.

Long afternoons on the lake shore, the Ghetto’s strange old Jews, the foreign quarters, Polish, Irish, until–

“We don’t ‘low no n***rs in this street.”

“I’m not bothering you.”

“Makes no difference. We don’t ‘low no n***s in this street.” And the lanky boy stuns me with a blow to the jaw. A shrill whistle brings the gang. Blows and counter-blows, oaths and kicks. We butt and fight and scratch. I would run but someone knocks my cap on the ground. My old dirty cap on the ground. I’ll get my cap. It becomes life, death, God, everything,–my cap.

“Let me get my cap! Fight fair, you poor white cowards! Ganging a fellow like this!” We sway and grunt and pant, a mass of fists, arms, bodies. I grab someone’s legs, kick, shove, reach down, grab my cap turn, push, run. Escape! A whizzing of stones. Street corner, head out, body safe.

“Bastards!”

“N***r!”

Chicago before the riots. Power and brutality, strength. Ugly, sprawling, mighty city.

Mexico

I have come from far up in the mountains to the capitol for this Feast-Sunday. It is the bull-ring in Mexico. Juan Luis de la Rosa, youngest and most graceful of Spanish matadors, places the banderillos. With one gay, paper-covered, sharp steel-pointed dart held high above his head in each hand, the young fighter, in a suit of silk and silver, moves in a circle about the angry bull. The animal paws the ground, bellows, rushes toward him. Quick as a flash, the hooked darts are fastened in his torn skin. The fighter leaps aside. The surprised bull roars, turns. The colored, cruel instruments of the fight decorate his bloody neck, making him seem like some garlanded festival animal ready for the sacrifice. It has been a perfect placement. “Bravo, los hombres!” The crowd goes mad. Hats, scarves, jeweled combs, fans are thrown in the arena at his feet as the young fighter receives the acclamations of his public.

The bull has killed four horses, goring them till their entrails spill on the ground. The bull has wounded one man. Now the youthful fighter, ready for the kill, receives his sword and cape. The vast crowd about the great ring is silent almost to the point of breathlessness. The supreme moment has arrived, the crisis in that savage drama, that old, old drama of youth against odds, youth against evil, death, the beast. The bull, tired by the exertions of the fight, stands still in the center of the arena, panting, but his stillness is pregnant with unused strength. Will he rush toward the young man, gore him through, lift him high on his horns as he did the bodies of the bleeding horses? Will the drama end in human death?

It is late afternoon and the quick, tropical darkness is approaching. Already dusk is gathered over the arena. Hurry, oh, hurry! The nervous stillness of the crowd is like a scream. The fighter advances slowly, his red cape before him, his sword held high. The bull paws the ground, seems to moan deeply, gathers his waning strength and rushes forward. The sword goes straight and deep into his neck. The fighter, in his suit of silk and silver, is lifted high in the air between the horns of the bull. He springs back. The mighty moment of the drama is over. The dying animal stops, takes one, two steps toward his human slayer, trembles, then slowly and in a manner of great state, like some ponderous animal god, topples down in the sand to death.

Already it is dark. The crowd, making for the exits, fills narrow steps, pushes in enclosed corridors. A great number of men and boys climb the high barrier into the arena and carry the young triumphant fighter off on their shoulders. I follow shouting, pushing with the rest, trying to get near, to touch this hero of the day and dusk. Through the dark stone arches of the plaza, through the toreadores’ quarters, out to the waiting long powerful car with head-lights softly glowing, they carry him. In the car, with much cheering, they place the young matador. One of his friends throws a ring-cape of pale grey silk broidered in gold about him. The flash of a match shows me his face as he lights a cigarette,–a hard, sun-browned boy-face, scarred, shadowed. Tomorrow the newspapers will headline his name and in all the little bars and cafés, theatres and great restaurants of the capital, they will talk about him. The people will idolize him. The loveliest of courtesans will offer him their bodies, and the international news reels will flash his picture on the screen in Canton, China, and Kenosha, Wisconsin. He has fought the good fight and brought to a triumphant end the drama of youth against odds, youth against evil, death, the beast. He has played his part well in the afternoon’s savage and primordial spectacle.

Down the narrow street, through the talking crowds, out into the wide Avenida, his car glides silently. The space it leaves in passing fills with moving crowds as a mud-rut fills with water after the passing of a wagon wheel. I am lost in the moving crowds, lost with my two friends speaking rapid Spanish on the brilliantly lighted sidewalks of the avenue, lost in a maze of wild, beautiful people. Oh, the ecstasy of crowds; the joy of lights; the fascination of cities!

New York

The sea brought me to Manhattan. Days and nights at sea. Sultry days, starry nights, and then suddenly, rising from the very waters themselves, the living cliffs and towers of New York. There is no thrill in all the world like that of entering, for the first time, New York harbor,–coming in from the flat monotony of the sea to this rise of dreams and beauty. New York is then truly the dream-city, city of the towers near to God, city of hopes and visions, of spires seeking in the windy air loveliness and perfection.

I am anxious to disembark. Quickly I want to be ashore, to touch its life, to mingle with the crowds in its deep canyons, to walk in the shadow of its strong towers. I want to be one of the many millions, one of the many moving living beings in the swirling greatness of the city.

I go. Manhattan takes me, is glad, holds me tightly. Like a vampire sucking my blood from my body, sucking my very breath from my lungs, she holds me. Broadway and its million lights. Harlem and its love-nights, its cabarets and casinos, its dark, warm bodies. The thundering subways, the arch of the bridges, the mighty rivers hold me. I am amazed at the tremendousness of the city, at its diverseness, its many, many things, its spiritual and physical playthings, its work things, its joy things. I cannot tell the city how much I love it. I have not enough kisses in my mouth for the avid lips of the city. I become dizzy dancing to the jazz-tuned nights, ecstasy-wearied in the towered days.

The sea takes me away again. I am glad. But I come back. Always I come back. The fascination of this city is upon me, burning like a fire in the blood.

Paris

Springtime—Paris–Dusk, opalescent, pale, purpling to night–Montmartre. The double windows of my high little attic room open to the evening charm of the city.

“C’est très grand, ce Paris,” Sonia says. “Vois-tu Notre Dame là bas, et le Tour?” And we search for the things we know in the darkening panorama of the vast town. We search for the things we know and watch the lights come out beneath us and the stars above.

“C’est très beau,” says Sonia. “Oui, c’est très beau,–this old, old queen of cities.” And I think of the many illustrious ones who, through the centuries, have been her lovers,–Dante, the exile; Villon of the ragged heart; Molière and the great Lecouvreur; Heine, Napoleon, the little corporal; the strange, satanic Baudelaire; Wilde, and the gorgeous Bernhardt. And I think of the seeking wandering ones she has drawn from all the world,–poets, students, adventurers and lovers. And I think of her as the center in the great wheel of cities circling around her,–New York, London, Berlin, Vienna, Rome, Madrid. And in the darkening day she becomes like an enchantress–city adorning herself with lights. She becomes like a sorceress-city making herself beautiful with jewels.

“Allons,” says Sonia, who all the while has been standing quiet in the shadows. “Oui, allons,” I answer. And we go together down the winding stairs, out into the living streets, eagerly into the moving life of the Paris night.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/details/sim_crisis_1926-01_31_3/page/140/mode/1up?q=%22langston+Hughes%22&view=theater