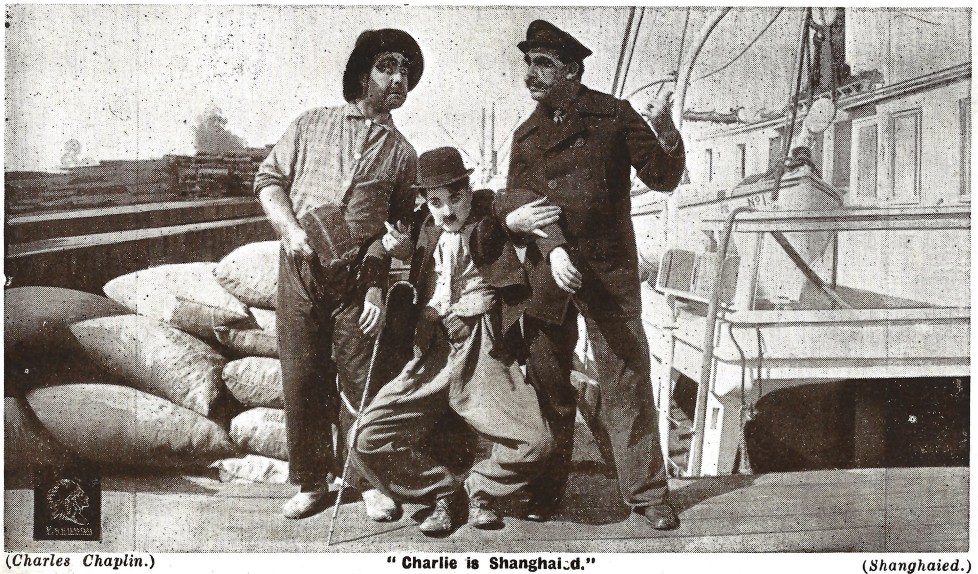

Another chapter from Tom Barker’s classic serial, ‘The Story of the Sea,’ this one the coercion and kidnapping of sailors onto ships. Barker was a self-educated, working-class Marxist, a leading figure in the New Zealand and Australian I.W.W., deported to Latin America for his anti-war and union activities, where he worked the Buenos Aires docks and became a leader of the international marine workers organizing and delegate to the Red International of Labor Unions.

‘The Shanghaiers and the Shanghaied’ by Tom Barker from Industrial Pioneer. Vol. 1 No. 2. March, 1921.

ONE can hardly deal with the question of the marine transport industry without touching upon the old-fashioned business of “shanghai-ing.” We are glad to say that it is now disappearing. Some years ago it was very prevalent in ports of the United States, England and South America, reaching its highest mark in the ports of the last-named continent. It really had its origin in runaway seamen who hid themselves away from the authorities while waiting to get another ship. The desire for freedom on the part of the seamen of the period really originated this vile and iniquitous system. In return for the services of the man who was accommodating him, and using his offices to supply him with another ship, the man signed an “advance note,” which gave this individual the right to collect one or two months’ wages belonging to the man after the ship had cleared the port. From these beginnings grew up that business of shanghaiing, in which the shanghaier was involved with the captains. Sometimes the consuls were in the game; at times also officials of the various missions got their “whack” out of the proceedings. Even the sanctified “soldiers” of the Salvation Army have had their fingers in the pie. From efforts to protect and assist the runaway seamen was developed a monstrous system of blackmail, thru which these harpies stripped the seamen of their money before they had earned it.

Tommy Moore’s Way.

Shanghai-ing reached its high mark in Buenos Aires, which is the largest port south of the Line, and the biggest sailing-ship port in the world. More men are shipped on foreign-going ships in that port than in all the other ports in South America combined. Owing to the fine climate and the amusements, which are unexcelled by any other city in the. world, it is also a favorite port for paying off men. Let us suppose that a sailing ship arrives in the roads of the River Plate. The men will probably be taking in sails when Tommy Moore’s motor launch comes alongside. Tommy has a body-guard of half a dozen big toughs with him. He climbs the rope-ladder, shakes hands with the waiting captain, and then the two clear down below into the captain’s cabin, where Tommy’s bottle of whiskey is opened up. After a conversation with the skipper Tommy comes out on deck and roars out to the men in the rigging who are just finishing stowing sails, “Come on, you fellows, you’re all going to pay off.” The crew meekly swing down to the deck, and within half an hour they have their bags packed, and pass into the waiting launch and the hands of Tommy’s body-guard. In an hour or so the launch runs down the South Channel and across to the Boca, wherethe men land. Their traps are dumped in Tommy’s boarding house—save the mark—in Calle La Madrid. This place, curiously enough, passed into the hands of the Marine Transport Workers in 1919, after Tommy went on that long voyage that both shanghaier and shanghaied alike must make. In this dump the bunks were placed closely against the wall, so that is was as much like a foc’s’le as any place could be. The food was usually salt-horse, borrowed from Tommy’s skipper friends.

Now, in all probability these men may have had six months’ wages coming, but all that they were likely to see would be a ten peso bill—about $4.00—which they were free to spend on “vino carajo,” or on any other chained lightning or weed-killer that they fancied. The rest of the cash was cut up between Tommy and the skipper. You will observe, therefore, that there would be a good profit on Tommy’s boarding-house. At times some of the men used to kick, but Tommy’s body-guard was always on the spot, and the result was generally disastrous for the one who kicked. At times they emptied one of the men out on the street, which meant that his only way of getting a living was to go on the beach, or go to the “campo.” The shanghaiers had the jobs in their hands. There was no organization at all. These men would stay at Tommy’s “dump” until he got another ship for them.

A man might be married in New York, or have his home in Bergen, but that didn’t count with Tommy. He would probably ship that man to Callao or Melbourne. A man had to stifle his desires and keep a quiet tongue, otherwise he was apt to get his hair combed with a piece of gas-pipe. When Tommy got you a ship you went, either voluntarily or insensible, and that was all there was to it.

Before a man went to sea he had to sign an advance note for one or two months’ pay which went to the shanghaier and his clique. For this he would receive, if he was fortunate, a suit of dungarees, a pair of fine-looking, highly polished paper sea-boots, a bar of soap and a bottle of alleged whiskey or cana. There are men who have been thru Tommy’s dump a dozen times, and can still be met here and there. The story of shanghai-ing is one of the most enthralling in the world.

Some of the “Heads” in S.A.

Tommy Moore is dead. He died in bed. He made a fortune out of the business, and his son has today a big contracting firm in Buenos Aires. Another great “identity” was “Black Jack” in Rio de Janeiro. After the union was organized in Buenos Aires in 1919, a bunch of Scandinavian seamen gave Jack a beating-up one night and put that gentleman on crutches. They made a thorough job of him, as Scandinavians usually do. Up to September, 1919, “Big Fred” Williams was the chief shanghaier in Rosaria de Santa Fe. When we started the union and crippled his business he wanted to join the union, boasting that he had been a member for thirty years of Havelock Wilson’s burial society. He is a Swede and stands about 6 ft. 1 in. His complexion is ruddy, and not from the sun, either. He was somewhat ruddier when three Finn sailors—whom he had once shanghaied—met him in Buenos Aires one night after the union started.

Until May, 1919, “Big Pete” Frederiksen was the big gun in Buenos Aires, after the departure of Tommy Moore for his last anchorage. Pete was “Big Fred’s” brother-in-law. Denmark has the misfortune to own him as a citizen. After we had broken up his business, he and his colleagues attempted to start a scab union solely for ‘“Scandinavians.’’’ The secretary resigned his job after he had received a slight concussion one dark night from a mysterious captain who interviewed him near the transporter bridge in the Boca.

The shipping for British ships was usually handled by an individual named Nelson, a Russian. This fellow was in good standing at the British vice-consulate in Calle San Juan. He was round the consulate far too much for its reputation. It is also true that the vice-consul preferred to ship men from him rather than from the Sailors’ Home, although he is a most disreputable character. While the war was on, the German officials in Buenos Aires were very anxious to repatriate their countrymen for military service. They gave this job over to a Dane named Bangtsen, who used to get the men berths in Scandinavian ships, from whence they arrived ultimately in Germany. But Senior Bangtsen was a clever man, in fact, he had the makings of a diplomat in him. He paid a visit to the British authorities and sold the information that the men in question were on such and such a ship. The result was that the ship was held up in the open sea, and the Germans taken off and interned. Bangtsen used to shanghai men on the American schooners. After the union started he ran into a big fist more than once.

“Stockholm Charley” was another well-known “identity”, who had a reputation for swiping men about half his size and half-killing them. O.L. Kruse was once a waiter but found that shanghaiing was more lucrative. It is said that he used to make 25,000 pesos a month from fees, etc. He also owned a big bar near the “Green Corner,” but the sailors smashed it up for him one Saturday evening in December, 1919.

Some Stories of the Business.

Writing of shanghai-ing, reminds me of Tommy Moore once shipping a dead man. When he was thrown aboard a ship in the roads with the rest of the drunken sailors, the captain looked at him and said, “He looks pretty bad.” “That’s all right,” replied Tommy, “he’s only drunk. He’ll be all right tomorrow morning.” But when they tried to get him out, he wasn’t all right, so they had to get a piece of old sail-cloth, and place him to rest in the waters of the River Plate.

There was once a conscientious skipper who hated the shanghaiers and who decided to pick his own crew. This didn’t fit in with Tommy’s requirements at all. When the captain was drinking in a bar one night, his drink was drugged. When he awoke three days later, he found himself on the high seas on a sailing-ship, signed on as an able seaman and bound for the other end of the earth.

“Big Pete” himself was once shanghaied, when he was a “runner”—he was learning the business—for Tommy Moore. Tommy and Pete took a crew of fifteen men out to a ship waiting in the Roads. Pete went aboard with the crew, and Tommy stayed on the boat. The captain counted up and found there was a man short. He bawled to Tommy, “Hey, Tommy, there’s a man short.” “Is that so?” replied Tommy. “Well, then, you’d better take the runner. He’ll do.” With that he pushed the launch away from the ship and left Pete aboard as a sailor. It took Pete two years to get back again.

What It Meant to the Seamen.

The shanghaiers made their money from the unfortunate and unorganized seamen. They spent it like water. You could see them at the race meetings at Palermo every Sunday afternoon, where they used to literally wash the floor with champagne. Motor-cars, prostitutes, big hotels and plenty of high-priced booze were the results that these harpies got out of swindling the seamen. Jack the Sailor footed the bill for the lot.

Villainies were perpetrated upon him If he stood on his feet like a man he was driven to become a “beach-comber.” A sailor was nothing in the scheme of things. He had no organization, no friends, and no one to assist him. The consuls despised him, the captains logged him to their heart’s content, and the missions, as usual, worried more about his spiritual needs than his material comforts. He might be a union man in New York or London, but his union could not help him in South America, nor did it ever cross their fat heads that it was at all necessary. The native unions didn’t speak his language, and he didn’t speak theirs. The police authorities gave the shanghaiers carte blanche to follow their odious business.

In Europe and the States the shanghaier has changed his name to the more euphonious “shippingmaster.” His existence is not seriously attacked by some of the marine unions, which are notoriously short-sighted. The ports of the world are infested with “beach-combers.” They are the cast-offs of the sea. Some are loafers, but many are good men and true. This army is growing, and hungry and unemployed sailors and firemen can be found everywhere. But they are waking up. The march of events and the drive of the machine process is compelling these outcasts to come together in the Great Brotherhood of the Sea. Their nationalities, their religions and their tongues may differ, but they suffer from the same privations, live the same lives, and die the same deaths. They have the same ruthless masters and the same grinding poverty.

From all the corners of the Seven Seas they are coming together in One Army. The black night of disorganization and ignorance is clearing for ever from the face of the ocean. The bright sun of the Marine Transport Workers’ Union, international and universal, is rising in the East. The sea is roseate with the coming day, and on the foc’s’le head there are many watchers waiting to greet the Day of Emancipation.

Men of the Sea! Let us encircle the ocean routes and the docks with ONE UNION, ONE CARD and ONE OBJECTIVE. Long live the democracy of the stokehole, the engine-room and the galley!

All power to the Workers of the Sea! Long live the Industrial Republic of the Ocean!

The Industrial Pioneer was published monthly by Industrial Workers of the World’s General Executive Board in Chicago from 1921 to 1926 taking over from One Big Union Monthly when its editor, John Sandgren, was replaced for his anti-Communism, alienating the non-Communist majority of IWW. The Industrial Pioneer declined after the 1924 split in the IWW, in part over centralization and adherence to the Red International of Labour Unions (RILU) and ceased in 1926.

Link to PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/industrial-pioneer/Industrial%20Pioneer%20(March%201921).pdf