Washington D.C. has long been a Black urban center, and as Young’s superlative investigative report lays out, a city where the nation’s white supremacy’s is authored and practiced. In part one, Young looks at the conditions of the city’s then one-fourth Black population, the history and practice of white supremacy in the Nation’s capital; in the second party she meets, powerless and puffed-up, members of Roosevelt’s ‘Black Cabinet’ as well as the first Black Democrat elected to Congress, Chicago’s Arthur Mitchell. A must read for background to the current racist Federal take-over of the city. Excellent.

‘Washington D.C.–Jim-Crow Capital’ by Marguerite Young from New Masses. Vol. 15. Nos. 7 & 8. May 14 & 21, 1935.

1.

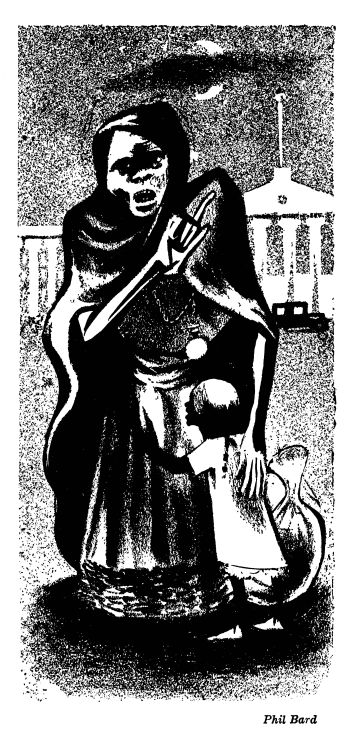

WASHINGTON, D.C. TEMPLE COURT: An alley off the corner of Canal and “D” Streets, Southwest. About ten houses huddling in a Negro ghetto in the shadow of the Capitol. There are at least two hundred of these hidden slums. They shelter ten to eleven thousand people, chiefly Negroes. Other thousands of the race live as wretchedly.

A junked touring car, rusting beside an overladen trash wagon, and half a dozen Negro youngsters, wearing grotesque pieces of cast-off clothes and soiled leg bandages around insect sores, define life in this swankily named lost street. Though it is hemmed in from the outside, and ends blind, its entrance looks over the low roofs of barrack-like houses across the street to the dome of the Capitol. There, like a huge bell, it shines white against the sky. Capitol Hill, with its cool magnificence of terrace and tenderly nurtured pink and yellow blossoms, is just a few blocks away; and atop the great dome, symbol of the wealth and power of America, stands a bronze “Goddess of Freedom,” serene as a peacock despite her view of Temple Court.

Washington is a two-world city as surely as any black belt metropolis. The black and the white spheres often meet, as at Temple Court; but such proximity merely etches deeper the Bourbon pattern of Washington, the Jim-Crow capital of America. It is a favorite boast of certain upper-class Negroes that here is the center of American Negro culture. Though this is not the case, it reflects the tendency of Negroes all over America to look to this city, this “federal ground,” as a haven. Ever since the Proclamation went out to the slaves who believed it truly meant emancipation, the Negro has been taught to look this way for equality. Many a Negro intellectual, when he thinks of Washington, still pictures the classical perfection of the Lincoln memorial where the Emancipator’s statue is encolumned in marble. To thousands in Dixie, this is the gateway to the North. But in fact it is the gate to the South.

Always a border town, a reflecting-pool, mirroring all the special abuses and prejudices generated by white ruling-class forces against the Negro nation they oppress, it presents today, more than ever, a composite of the myriad Jim-Crow brutalities. For with the advance of fascist forces, increasing lynchings (to name but one indication) point to the role for which they have cast the Negro–the same dread role they gave the Jew, the scapegoat, in Germany. It is a prophetic fact that since the installation of the fascist-tinted New Deal, this federal ground, whose local administration expresses the conscious political program of the national government, strikingly reflects the Bourbons’ swashbuckling return to power. These political descendants of the plantation lords who rushed toward a foothold in national politics with the collapse of their slavocracy in the Civil War are more prominent on the scene than in years. They stick out everywhere in the highest ranks of the Army and the Navy, at the pinnacle of the diplomatic service, on the most powerful committees in Congress, including the one which runs the District of Columbia. Their lynch language, their hate-the-Negro creed, their employment practice of exploiting the Negro doubly, their ingrained Jim-Crow social cruelty envelop this ground like a dust storm.

The 135,000 Negroes in Washington make up more than one-fourth of the whole population. Theirs is a restricted, branded political and social life. They have been pushed down to a markedly low rung on the economic ladder. Four out of ten are unemployed. With their total of 27 percent of the whole population, they suffer exactly 76 percent of the forced joblessness registered by the official relief rolls. Regardless of skill and education, the vast majority must work at menial tasks. This is so axiomatic that many a skilled artisan, when applying for public or private employment, forgets about his trade and asks for common labor because he knows that otherwise he will get no work at all. Just look at the last Census figures: among the 41,811 employed male Negroes there were 11,283 in domestic and personal service; 10,990 in manufacturing and mechanical pursuits which break down into baking, hod-carrying and such jobs which are, on the whole, common labor in character; only 3,997 listed in trade and this included 1,596 laborers; and only 1,793 in the professions. Of 31,311 employed women, exactly 26,500 were in domestic and personal service, only 1,610 in the professions and most of these were teachers in Jim-Crow schools; and the 1,695 classified in manufacturing and mechanical pursuits were chiefly seamstresses.

All Negroes, regardless of their work, are universally denied the right to eat in public places throughout the great central white business and residential section of Washington. The federal government itself Jim-Crows Negroes in department dining rooms. (In the Interior Department, a few pee-wee officials may eat with the whites, but the Negroes in the ranks dare not even try it.) James Boens, a Negro delegate from an A.F. of L. auto local at Flint, Michigan, was impolitic enough to bring this to the attention of government and labor bureaucrats quite dramatically last spring. It was during the National Labor Board’s hearing on the then scheduled auto strike. Boens stopped the proceedings by suddenly interrupting to inquire how he was supposed to get food in the short recesses which provided no time to journey to “I’m a Negro neighborhood. hungry,” Boens pronounced sharply. “For the first time in my life I cannot buy anything to eat.” The official gentry, including Presidents William Green of the A.F. of L. and John L. Lewis of the United Mine Workers of America, remained discreetly silent–mindful, perhaps, of the Federation officialdom’s policy of Jim-Crow unions, and of its thwarting the rank-and-file surge toward unity by promising to appoint a committee (never yet named) to look into the status of Negro workers in the A.F. of L.

It is a fact that not even the hot-dog stands and orange juice palaces around the whited sepulchres which house the government will serve a Negro; nor will the drugstores; nor, of course, the restaurants.

Shopping is on a strict Jim-Crow basis in Washington. The stores along the famous wide boulevards, Connecticut Avenue and “F” Street, rigidly exclude Negroes. The ritziest department store, owned by a Mr. Julius Garfinckel who (like most wealthy Jews) places class ahead of race interests, prides itself on employing only “Aryan” saleswomen, and refuses Negroes admittance without a note identifying the bearer as a servant shopping for a white customer.

Many other department stores discriminate against Negroes while seeking their trade. I saw this work. I happened to be on one of the upper floors of Hecht’s, the Macy’s of Washington, when a saleswoman reported to her chief that a Negro woman “refused to leave” after trying on three garments! Yes, I was told, it was “policy” to try only three things upstairs. “Of course” the store encouraged Negroes to buy “in the basement!”

Washington has a large number of “white taxicabs” and “colored taxicabs.” I have seen a feeble old Negro woman standing with her small granddaughter at the exit of the Union Station long after midnight–have seen them stand and wait and wait, passed up by one after the other, until the starter said, “You can get a colored cab out there.” Which meant outside, beyond the parking space reserved for the white companies. In Negro neighborhoods I have been passed up by cruising “white taxis”–on the apparent assumption that anyone who would walk there must be a Negro. I have taken “colored cabs,” too, and noticed a look of surprise and hesitation on the face of the driver unused to white fares.

Jim-Crowism glares out of the columns of the white press of Washington. Pick up any newspaper list of neighborhood movie bills. The names of a few in the long list are starred. At the top of the column appears the explanation “Colored.” Virtually every public recreational, cultural and educational facility here operates meticulously on a Jim-Crow basis.

“Perhaps the outstanding social insult to the Negro in Washington is the rule of segregation to the point of exclusion from artistic and cultural affairs,” Mrs. Mary Mason Jones, head of the Jim-Crow Negro teachers’ union, told me. “You know, artistic talent is a notable heritage of our race, but we are denied not only white artists but also those of our own race. Once, if you could suppress your pride sufficiently, you could give a little treat to your aesthetic need at the price of running a gauntlet of frigid gazes and passing down the left side of a balcony in The National Theatre. But no longer, even that.”

“White” hotels in Washington register no Negroes. The American Sociological Association held its 1925 convention in The Washington just across the street from the United States Treasury and now the home of Vice-President Jack Garner, Texas landholder and banker. A distinguished educator among the delegates, Dr. E. Franklin Frazier, now on the faculty of Howard University, stepped into a passenger elevator on the tenth floor of the hotel. He had gone up with one of the white professors. The elevator dropped a few floors and slowed. The operator, who had just noticed Dr. Frazier, asked sharply, “Who brought you in here? Who got on with you?” Dr. Frazier replied, “I didn’t notice.” A hostile buzz rose from the well-to-do white men in the car. The boy brought the car to a sickeningly short halt and shot it back up to the top floor. As he flung the door back, someone booted Dr. Frazier into the corridor, shouting, “Why don’t you go back to Africa?” There was just time, before the door slammed, for Dr. Frazier to retort quickly, “Thank you, I think I’ll stay in America with white savages.” In a moment the police were there. They forced Dr. Frazier to the freight elevator. Then he discovered the existence of an arrangement whereby the Negroes attending the conference would either travel “freight” or be escorted by whites like poodles. A number of upper-class-conscious Negro “leaders” had accepted this! Dr. Frazier made an issue of it. Finally the Association secretary saw the manager, who cried, “No damn n***r’s gonna ride in my elevators, I don’t care who he is!” Result: the convention moved down to the second floor so that participating Negroes could walk up.

Such Jim-Crow attitudes so pervade the capital that it is somewhat surprising to find no legal segregation. The absence of this and a few mores constitute the chief difference between Washington and, say, Birmingham. The latter are mainly a matter of the degree of anti-Negro social etiquette, too. Down South there are parks through which a Negro may not drive; he may enter any park here, but he is Jim-Crowed on the park’s public tennis courts and golf links. The noose and the faggot do not threaten him here if he fails to “Sir” a white man; but neither is he “Mister” to nine-tenths of the whites. When he comes into the District of Columbia in a street car or train

that runs over the bridges spanning the Potomac river, he may move out of his Jim-Crow seat. But what can this mean in an atmosphere in which the Jim-Crow mentality teaches children never to sit alone on a two-seated car bench–to find one already occupied by a white person and fill it, thus eliminating the risk of having a Negro sit next?

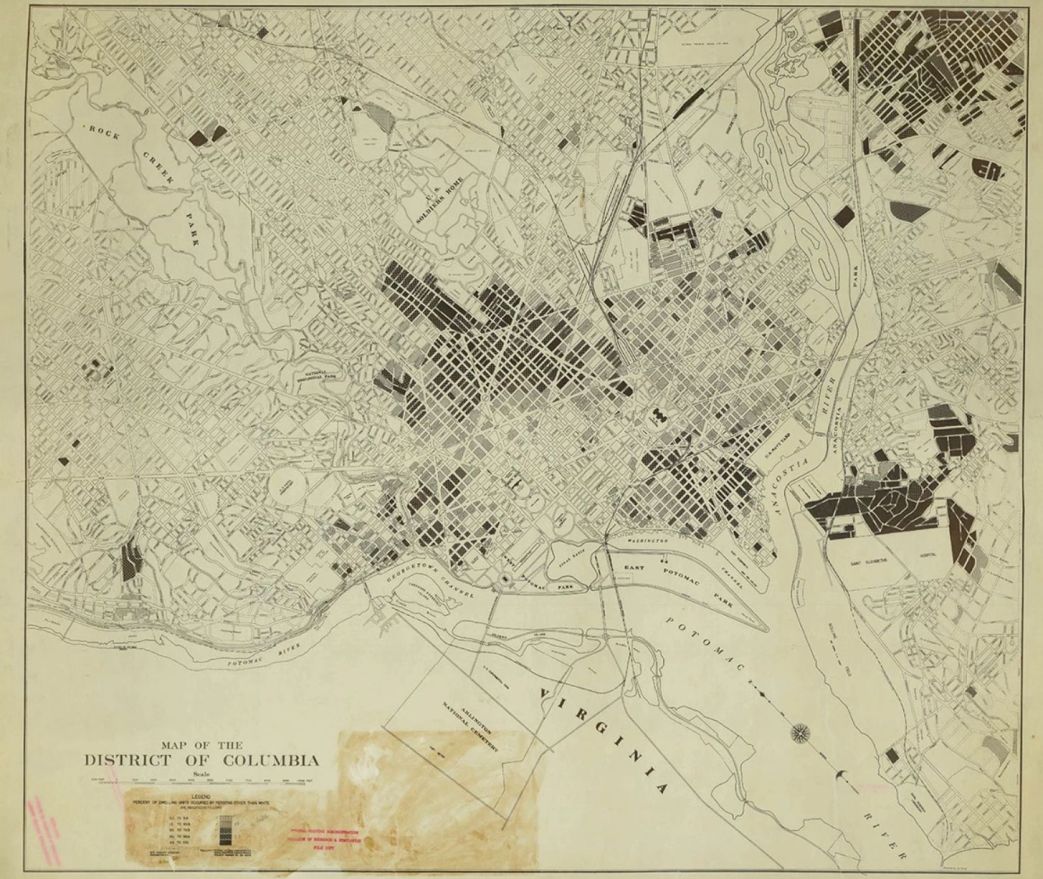

The courts do uphold residential segregation in one way. They sustain legal contracts binding white property owners within certain blocks and squares in “voluntary” agreement not to rent or sell to Negroes. Which gives the lie to the often repeated boast that Negroes may live anywhere in Washington. But the whole physical structure of the Capital shows this. In addition to the alleys, there are a number of vast sectors inhabited almost wholly by Negroes, as there are great lily-white domains. The fact that they are often contiguous emphasizes the division. It has resulted in a separate Negro city-within-the-city. There is a central Negro boulevard, “U” Street, with its Negro bank, its Negro shops, theatres and law offices. There is Seventh Street, which is to “U” what “F” Street is to Connecticut Avenue. Seventh Street’s cheap eating joints and radio-blaring stores constitute an important Negro business section despite its reputation as the habitat of a distinctly “lower-class” group.

The “upper-class” Negroes also dwell in segregation, however. The creme de la creme aspire to a “Strivers’ Row” of their own along “S” Street as near as possible to Connecticut. Their social life is a tight round of bridge, summering at Highland or Colton beaches (Jim-Crow) driving, weekending in Harlem or Philadelphia, and entertaining friends at the dances given by the “What Good Are We’s” club and other elite imitations of the dreadfully monotonous white “society” groups. Theirs is the creed of “It’s better to reign in hell than serve in heaven.” All this in an effort to forget they are part of the oppressed Negro nation, though ironically they also sometimes draw color lines within the color line, and not only shun but actively oppose the fight for Negro rights which is being led by the Communist Party. They contribute to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and send their children to Howard University. This Negro college (tuition fees higher than those of the average state university) is supported partly by federal funds. The fact that its student body is increasingly alert to the working-class movement is due to no fault of its administration.

Howard University is ruled by the tyrannical Dr. Mordecai Johnson, a former Baptist preacher who was once undeservedly accused of radicalism but has since wiped his escutcheon clean by pandering to whichever major political party is in the saddle. Its faculty leaders are such men as Dr. Charles Houston, N.A.A.C.P. lawyer whose answer to being exposed is to try the more frantically to prove his client, George Crawford, guilty of murder; and Dr. Abram L. Harris, the prima donna of the Harris School of “Marxists” who know enough about the class struggle and their own upper-class interests to remain carefully out of the revolutionary ranks where the fight for Negro rights is being waged.

More fundamental than all the social and political expressions of Jim-Crowism, however, is the economic discrimination against the Negro in Washington. In fact the anxiety to inspire prejudice and hate toward the black worker, the chauvinist fiction of “white superiority,” is but a rationalization, an effort to provide an excuse for the bedrock ruling-class policy of divide and rule.

And, quite naturally, the federal government leads in applying the program of economic discrimination on this federal ground. It is the big industry of Washington. It deliberately condemns Negroes, by and large, to the jobs of elevator operator, charwoman, messenger, and, rarely, clerking. Lucky is the one who rises higher even in the sacred realm of the civil service merit system. Every application must have attached a photograph of the aspirant. A Negro who qualifies in the written examination and is certified among the three highest-ranking participants still must face the head of the government bureau having a vacancy. This white official, exercising arbitrary authority to choose, rarely selects a Negro.

Among the 8,500 workers in the Naval Gun Factory, there are 4,200 machinists and 2,500 laborers and helpers. Half of the latter are Negroes, but only about half a dozen of the race are in the skilled group. A “classified” laborer may work into the slightly better-paid bracket of helper, but by more than coincidence the Negroes advance less rapidly than the white workers. All Navy Yard bosses are white. By the constitution of the A.F. of L. union, Negroes are excluded from the machinists’ organization.

The extreme discrimination against the Negro toiler who is lucky enough to escape the rule for his race–last to be hired, first to be fired–is reflected even on the garbage trucks in the streets. Drivers are usually white; dumpers, Negro.

Among the four out of ten of the jobless Negroes, the color line is drawn with the most refined cruelty. Instead of seeing in the great preponderance of Negroes on the relief rolls the obvious proof that they suffer more than whites from unemployment, the politicos of the white ruling class constantly point to this as evidence that Negroes “get more” from the relief setup. Such a characteristically chauvinist attack was launched with veiled brutality against the race in a recent relief survey by the white liberal Scripps-Howard Washington News. It published a study which recognized of necessity that reliefers “may not have enough to eat, and they may not be warm enough, and their homes may be pretty bad,” but nevertheless, with typical sadistic smugness, it concluded that the relief set-up “is now so efficient and so humanitarian that there are very, very few who need be hungry or cold or homeless.”

There is more than a coincidence, again, in the circumstance that the family average doled out among the predominantly Negro unemployed in this capital city was reported officially as $26.64 for the month of December, 1934, while the average in thirty-two other cities of similar size was $30.21. (Relief administration figures.) This, in addition to the fact that the cost of living here is higher than in many other cities.

Against all this the challenge of mass action is being flung. Small Unemployment Councils are organizing the workers who, beset by every official hindrance to unity, seethe with determination to overcome them.

“It’s a tough proposition we’re up against,” said William Strong, the Negro youth who led them during the winter, “but we have been able to win some victories nevertheless.

“The relief officials boast about how many Negroes are on the rolls. Well, they’ve got the names on the list, hundreds and hundreds of them, and that’s all. There’s a great difference between what we’re supposed to get and what we do get. The checks don’t come. Take the case of Melina Thompson and her two children. The relief officials promised, day after day, to supply her rent. They knew she had an eviction notice. But they just kept promising until they promised her furniture right out on the sidewalk. She was dispossessed while we were holding a meeting in the neighborhood. We went around in a body, about thirty-five of us. The police came. We told ’em we didn’t have much time to talk because these people had to get back in their house and get some sleep, and we had a heap of furniture to move back, and it was already after midnight. We did put it back, every piece of furniture, and the cops didn’t dare interfere. Finally, they went away. We stayed through the night, all of us, just in case of trouble. Nothing happened. In the morning we all went to the relief station and demanded $25 to get Mrs. Thompson another house. The superintendent handed it over. And she was trembling! Then we saw the marshal and told him never mind bothering to move our comrade. They didn’t move her either; she stayed until she got another house with the $25.”

Strong himself gets $20.80 a month for all living expenses for himself and his wife. There was a time when it was $4.90 a week. He went to the relief superintendent for a food slip.

“You got your money this week,” the relief official accused.

“But I get only $4.90 a week, and my rent’s $4,” he replied.

“Well,” she asked triumphantly as though this settled everything, “didn’t that leave you 90 cents?”

Add to this attitude, which is widespread in relief officialdom, the fact that the system provides budgeting according to the official’s concept of the need–a concept colored both by prejudice and the pitiably low level of the employed masses–and you can figure why the weekly allowance runs as low as $3.50.

“There’s an established practice of paying half your rent and telling you to get the other half,” Strong went on, “yet if they discover you have any part-time work, off relief you go. Take the case of Susie Stamps, a widow with three children; they discovered she got a job sweeping a church every Saturday afternoon, for which the pastor gave her a dollar; they closed the case three months ago, and we’re still fighting to get her back on relief.”

It is always violence, direct or indirect, that sustains the status quo wherever the masses are exploited; here visible terrorism is employed against the Negroes. The police of Washington are a lynch-spirited brigade. In the performance of their function of “keeping the Negro in his place,” they do not blink at murder. False arrests, illegal detentions, general rough-handling–these are just everyday bulldozing. What backs it up is that police as well as white property owners kill Negroes, confess, and go free without so much as a trial.

Policeman Southard shot Robert Lewis, a Negro youth, near the United States Government printing office. While the boy lay dying in a hospital, Officer Southard, exonerated by a lily-white coroner’s jury and detailed to his same beat, was swaggering about “G” Place intimidating his victim’s neighbors against organized protest, punctuating his yells with his nightstick: “Beat it!” “Cut out that congregating!” “Get in that house off this sidewalk!” The explanation was self defense, but the lad was shot in the back.

In one of the perennial investigations of the Washington police administration, it was indicated recently that the real director of the force for years has been Representative Tom Blanton of Texas, the Simon Legree of the District of Columbia Committee of the House. Blanton is always insinuating that there are too many Negroes in Washington anyway. Why don’t they go back to “their” farms, he asks, as though he never heard that most Negroes are held in peonage under the tenant and share-cropper system.

Blanton should and probably does know that more than 40,000 of the ancestors of today’s Negro population were propelled to Washington during the reconstruction years by the fair hope that though their “forty acres and a mule” dream was dead, they might yet find equal opportunity as wage earners in this gateway to the North where the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments were made. Some Negroes were stranded here at the end of the Civil War in which they fought with the Northern troops against the feudal slaveowners; still others were dumped here by Northern officers who had confiscated them and bundled them along with other contraband.

What a life awaited them! They found themselves in alley slums as socially degrading as the old slave quarters down home, and more menacing to health. With Bourbon ingenuity, Washington pushed the dark newcomers into the backyards between the wide streets which had been planned in keeping with the spaciousness of the rising bourgeoisie’s ambitions. Soon three hundred populated alleys teemed with the filth of over-crowding and unenlightenment. Then, of course, disease. Pneumonia. Diarrhea. Syphillis. Tuberculosis. By 1875 the death rate among Negroes was 100 percent greater than that among the whites. At last the ruling class, realizing that its health also was in jeopardy, began to reform the alley evil. With each campaign, the date of the promised “eradication” moved forward. The New Deal of course set up its own Alley Dwelling Authority under a new law envisioning the razing of the alleys–by 1944! The limited appropriation, $500,000, is not intended to be used for low-cost housing projects, John Ihlder, executive officer of the Alley Dwelling Authority, reminded me. He admitted he feels “we are morally obligated to work with other agencies to see that houses are available,” but stressed that his main job is to “reclaim” the alleys by converting them into garages, parking lots, other commercial structures and, lastly, playgrounds. He added, “Of course the work is entirely new and we must submit every step to legal authorities…We are clearing the legal way. We are working on fifteen alleys…No, we haven’t completely torn down any yet.”

Actually, the conditions under which the street-dwellers live are often as bad as those in the notorious alleys. There is Marshall Heights, the Negro Rooseveltville on the outskirts of the city, where Negroes piece together huts of cast-off lumber, tin cans, beaver board, scraps of rusted corrugated iron or packing boxes on land which is “sold” at rates as low as $2.50 per month. I was there the other day. Rags and pasteboard served instead of windows for many, but one clean little house had glass panes and brave white curtains. It was only two rooms. The worker, his wife, and their five bright-faced, carefully polite little girls possessed only two slender single beds and one decrepit cradle. Very little other furniture was theirs, besides home-made packing-box chairs. No lights, no gas, no toilet. They must carry their drinking water from a spout two miles away.

I drove through a small territory in the Southwest section, almost within hearing of the Navy machinery which is working faster than ever for the war in which will be slaughtered those who survive their peace-time conditions. Row on row, block after block, these squat Negro tenements stretched. Women and children hung out of the windows. Many in these jail-like structures hadn’t one window per inhabitant. The predominating detached home was a flat-roofed frame shack like a matchbox standing end up. Often they sagged against one another, desolate as breadliners.

In this section, during the hysteria following the last war, Negroes barricaded themselves in their homes to meet the fire of “law and order” in the 1919 race riots. Negro soldiers at Camp Mead, Maryland, started to march to their assistance under the command of their Negro non-commissioned officers–something which hastened demobilization. In one of these houses a Negro girl shot and killed a white policeman. She fired from her retreat under her bed–which tells the story.

The Negroes in Washington know all these forms of special oppression and most of them intuitively recognize them as such. They long to free themselves. Discontent and disillusionment are everywhere. But many workers as yet cannot and most of the intellectuals will not recognize the connection between these things and the imperialist rule by which the big bankers, industrialists and landlords who own everything and run everything, including the government, hold the producers, the workers, in subjection.

Negro intellectuals, especially, know these things. They draw class lines between themselves and the others, telling themselves, “But I am not so oppressed as the worker.” However, as government clerkships have become scarcer, and clients or patients or pupils drop off because there are fewer jobs for Negroes in the construction gangs, the professional group also has been pushed down. Many give expression to their discontent through narrow nationalistic groups such as the New Negro Alliance, which recognizes mass action as the only hope, but turns its back on the white masses. The more honest stand ready to engage in the working-class program advanced by the Communist Party to emancipate Negro and white workers of the farm, the office and the factory.

2. “Friends of the Negro”

I SPOKE to Eugene Kinckle Jones about the Jim-Crow pattern of Washington. He should know. He is Advisor on Negro Affairs in the Department of Commerce, and was secretary of the influential National Urban League for twenty-five years. He did know. He said, “It’s so obvious to any colored person who comes into Washington that all life is on a Jim-Crow basis, I don’t know what to say.” Then he went on to explain why he is so acutely aware of this. The first-hand experience of “all life on a Jim-Crow basis” came as a shock to him because during all his previous years as a “leader” of the Negro masses, he had resided in a lily-white neighborhood in New York! Enjoying a certain individual tolerance in recognition of his service in the field of inter-racial cooperation, he had chosen to capitalize it by living in a “white” apartment house. “Not another colored family in a square mile of us,” he boasted. Ironically, he has to face the music in a Jim-Crow society personally, now that he is a Roosevelt official living on this federal ground.

He sat in his severely plain office in a deserted corner of the Commerce building. His Negro secretarial staff is segregated in the government dining room. (One personal privilege remains to Jones: at work, he eats with the white officialdom.)

There was an air of utter listlessness in this office behind the flagpole. I asked Jones just what his work was. He said, “I can take up any matter relating to Negroes. Any matter that would help to increase the Negro’s prestige and power. Of course, my work cuts across other departments’ activities, and naturally there is a certain amount of caution taken not to tread on the other fellow’s toes. But, in all fairness, I think Mr. Roper is for seeing that the Negro gets a fair deal that is, over against your system.” Roper is one of the New Bourbons, a South Carolina lawyer who became Secretary of Commerce after winning his spurs as counsel to those notorious exploiters of Negroes, the American sugar barons in Cuba. I let this pass, however, inquiring rather just what Jones knew about “my” system.

“I mean the Negro question–I mean that from your point of view, if there’s a change in the whole darned system, the Negro would take his chance on getting a square deal and I have no doubt he would. But retaining the capitalist system as it is– and I think we will for a long time–Mr. Roper’s attitude is to be commended.”

“Do you think the Negro can get justice under this system?” I tried to pin him down.

He replied, frowning, his long face a picture of mental somersaulting, “I believe that he will get it–which means that he can–as far as any poor man can. Of course poor white people can’t get ” he caught himself in mid-air, then reassured himself aloud, “But I guess there is nothing so radical about that statement. Chief Justice Hughes said about the same thing the other night.”

What did he think might remedy the Jim-Crow situation in Washington? He replied audaciously, “A Civil Rights bill.”

“One like the bill formulated by the League of Struggle for Negro Rights?” This is a militant measure, proposing death to lynchers and prison for anyone violating social and political rights of Negroes. “Yes,” he said.

“But you don’t support it, do you?”

For once Jones held his tongue. He merely smiled knowingly. I asked him to tell what he does do about Jim-Crowism.

“I came down here to do a national job,” he replied plaintively. “I can’t get too deeply involved in a local situation. I’m always having to be careful about that. I wish they wouldn’t always be asking me to make speeches around here. I’ve turned down I don’t know how many requests!”

WHY did the Roosevelt Administration plant Jones and several other prominent Negroes in conspicuous berths in Washington at the same time it set the pace of intensified discrimination against the Negro people? How does this concern the working people, both Negro and white?

Jones nearly put his finger on something when he mentioned “the whole darned system,” but he concealed the national character of the oppression of the Negro, the crux of it. In these days of imperialism “one group of nations [a minority] lives upon the backs of another group of nations whom they exploit.” In fact the imperialists, pressed by the crisis, redouble the national oppression of colonial and semi-colonial peoples all over the world. The 12,000,000 American Negroes are one of these oppressed nations. Some 9,000,000 live below the Mason-Dixon line today, constituting a majority of the whole population of the Black Belt that sweeps across portions of twelve states. This, with their lasting common language, economic life and customs, identifies them unquestionably as a nation. Recognizing the situation, the Communist Party supports the movement for national liberation of the Negro with the right to self-determination in the Black Belt, as the only road to full and lasting equality. It knows also that, just as the Negro could and did free himself from chattel slavery only by allying himself with the then revolutionary middle class in the Civil War, his only true ally today is the revolutionary working class, which in turn needs the Negro workers and share croppers in the struggle to throw off the yoke of wage slavery. But the white master class knows all this too, and views with increasing fear the sweep toward Negro and white working-class solidarity. In an effort to halt it, the white rulers call upon that reformist breed of Negro “leaders” who have always been upper-class foremen in the ranks of the Negro masses.

Sponsored by rich and powerful whites as well as by the Negro upper-class, the reformist leadership of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the Urban League and others perform a real service to the white top-dogs; they try to channel the Negro workers’ and farm laborers’ longing for freedom into “safe” expressions. They are “blurring over the basic class interests of the Negro toilers, and trying to kill their will for militant struggle by injecting liberal antitoxin.” It is for this task that Jones and his eminent fellow reformists have been summoned to Washington. One of their chief activities actually has been to travel over the country on speaking tours in an effort to sell the New Deal to the Negroes. They are the proteges of philanthropists who foster segregated educational and business projects for Negroes. The supreme trickery of their basic catch-slogan, “inter-racial cooperation,” was demonstrated just recently in Washington, when a white teacher in charge of “character education” told a group of educators how she handled a difficult (to her mind) situation. It seems there were two schools, one for Negroes and the other for whites, on adjoining lots. The children quite naturally ran from one playground to the other and mingled at their games. Instead of dealing harshly, the teacher explained, she picked a committee of the white children and sent them to their Negro playmates to propose that they establish inter-racial cooperation, and use the playgrounds at different hours.

Jones is a member of the “Black Cabinet” assembled by the Roosevelt government at the very time it was giving official sanction to the writing of N.R.A. codes by big business with clauses singling out Negro workers for added degradation. The irony is that the Negro petty officialdom of the New Deal enjoy less authority and political pap than did the original “Black Cabinet” of the Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft administrations. In those past days when Negro Republicans controlled 126 votes in the party convention, they had something to bargain with. They pulled down such plums as Fourth Auditor of the Treasury, Register of the Treasury, Collector of the Port of New Orleans. They lost ground during recent regimes and the Roosevelt government has not replaced them. It has called in, rather, a large group of intellectuals whose numbers in no sense indicate power. They are really just a splinter of the white “Brain Trust,” and, quite naturally, they get less for their pains than do the white professors for their intellectual prostitution.

The two most influential members of the “Black Cabinet” are half of the “Big Four” Negro Democrats. They won their reward by pouring molasses in the Democratic party’s campaign for Negro votes. They are Robert L. Vann, Assistant to the Attorney General, and Dr. William J. Thompkins, Recorder of Deeds. Happily for Vann, he has no jurisdiction in matters such as lynching, against which many militant Negro and white-worker delegations have registered protests with the Attorney General. Vann’s business (beyond the important matter of patronage) is to examine legal titles in the Department of Justice’s division of public lands. Founder of The Pittsburgh Courier (which is, practically, an organ of the N.A.A.C.P.) and a crony first of the Republican Mellons’ man, Senator David Reed, and then of the Democratic Mellons’ man, Senator Joseph Guffey, Vann shifted during the 1932 campaign. He had hawked for Herbert Hoover and been done out of a plum, so he turned to the Democrats with all his assets and with better luck. Dr. Thompkins’ job in the Recorder’s office (traditional patronage prize because it carries with it a hundred or more clerkships in the office) likewise was the pay-off for whooping it up for Roosevelt–something into which Thompkins threw considerable prestige, since he had been superintendent of a Negro hospital in Kansas City.

The most abject “Uncle Tom” of the “Black Cabinet” is Lawrence A. Oxley. He bears the title of Chief of the Division of Negro Labor in the Department of Labor, but when I inquired about his duties, a white official could only hazard contemptuously that he “thought” there was a Negro somewhere around the Department! A native of Massachusetts, Oxley is proud to have the lynch country of North Carolina as his adopted state, and the Bourbon Senator Josiah W. Bailey as his sponsor. There is also Robert Weaver, Negro Advisor to the Interior Department. But what does he do? “Who knows? I don’t think he does,” answered a Negro intellectual who knows her Washington. “Supposedly he talks to the Secretary of the Interior. Actually the job boils down to this: if a Negro seeks an explanation of some specific discrimination, Weaver concocts an answer.” It is my conviction that he takes his cues from William H. Hastie, Assistant Solicitor in the same Department. And Hastie, Phi Beta Kappa, graduate of Amherst and Harvard, Howard University professor, is in a sense the most intellectually corrupt of them all–for he is the ablest and the most keenly conscious of the imperative need for a meaningful challenge to the oppressors of his race.

THERE is a “Little Black Cabinet” too! It is far more insignificant–if you can imagine such nothingness–than the white Assistant Secretaries of the “Little Cabinet” after which it was named. In it are the Head of the Division of Negro Correspondence, whose title completely describes his duties, in the Federal Emergency Relief Administration; the Assistant Negro Advisor to the Interior Department; and several Negro technicians in the Subsistence Homesteads’ division of planning Jim-Crow projects. Once there was also Edgar Brown, a bearded journalist with a scraping manner, whose business was to attend Relief Director Hopkins’ and other press conferences, and inform the Negro press about the good works of the New Deal–after the conferences. A Daily Worker correspondent once embarrassed Brown by questioning Hopkins on his Jim- Crow policy; afterwards, Brown cringed about the offices drooling to his white superiors that the reporter who spoke up about the discrimination “made me ashamed of my profession.” At last Brown became so obvious in his racial truckling that he lost his usefulness and was let out.

Negro journalists are excluded from government press conferences so much as a matter of course that when they turned up last year to cover a hearing on the so-called anti-lynching bill sponsored by the N.A.A.C.P., they were seated after some difficulty at a Jim-Crow press table and barred from the public restaurants which always exclude Negroes on both the House and Senate sides of the Capitol. There are a number of Negro “working press” in Washington. None was ever admitted to the White House Correspondents’ Association, membership in which is required to attend the President’s bi-weekly press conferences. None has ever been seen in the press galleries of Congress in which white correspondents enjoy many special privileges. For about two years of the Coolidge regime, two Negro writers did stand in on the White House conferences by virtue of the patronage of the President’s canny Secretary, the late C. Bascom Slemp. He secured White House permission for Louis Lautier of The Afro and C. Lucien Skinner, who wrote for many Negro weeklies, to come in. Significantly, nothing happened until there was a shift of officers in the Correspondents’ Association. Then on the initiative of a few Southern Negro-baiters, aided by the lassitude of many of the press corps toward the lynch philosophy, they were bounced out. The technicality was that at this point, after two years’ attendance, the Negro writers were discovered to be ineligible. They did not write for daily newspapers and file stories by telegraph, the formal conditions for membership in the organizations.

The technicalities have been and still are sometimes waived. But in a pinch, of course, the favor of a ruling-class politician isn’t worth a hoot. When the Negro reporters turned to their protector, Mr. Slemp responded with a pious hope and a polite rebuke. He wrote Skinner that he had “thought” the Negro writer “complied with the rules.” He “hoped” Skinner would do so soon, but in any case, Skinner must remember “there must be some limitation” on admittance. Later, Representative Oscar DePriest, the Negro Republican Representative from Illinois, sought to dismiss the matter by solacing the Negro press with cards admitting them to the House gallery reserved for guests of the Congressmen. Of course it did not fool the journalists. They ventured to one of Postmaster General Jim Farley’s press conferences soon after the Democrats came in–and promptly were put out.

The national Democratic machine headed by Farley and Franklin D. Roosevelt took the trouble to place their own representative, Arthur D. Mitchell, in DePriest’s seat. I spoke to the new Congressman also about Jim-Crow conditions in Washington. I wished especially to consult him about some quotations I had seen imputed to him in both the white and the Negro press–declarations so openly cringing that, though I knew he had a reputation as the Number One Uriah Heep of the Negro people, I could scarcely believe them.

CONGRESSMAN MITCHELL received me with cloying courtesy, though he later told me to get out. When I referred to The Afro-American he warned me, “If it was in The Afro it’s false on its face. It must be, because we don’t allow their reporters in this office. They’re trying to make out I’m doing a lot of kowtowing and not It standing up for the rights of my race. reminds me of when I was at Harvard studying English. I had a class in short story writing, and the motto in that class was ‘Beware of the truth.’ The Afro operates on that motto.”

But when I insisted upon reading the quotation, he admitted, “Oh, yes, I said that.” This is how it read:

“A great number of us have the idea to raise a rough house in the D.C., but our duty is first to make friends there and my duty is to make as good a Congressman as there is in Washington. I did not go to the D.C. to make a lot of noise, regardless of what the half-baked, half-informed editors say…I want to make a correction. I don’t want any of you to get the idea that I represent a colored district in Chicago. It’s a mistake to believe that I am in Congress to represent my race.”

The Congressman added emphatically to me: “And I don’t represent a Negro district. There are 9,000 Italians in my district and 1,000 Chinese! And, more important, my district takes in all of the Chicago Loop. You know, that includes the whole financial district, the richest district in Chicago, the banks, the hotels, the office buildings—”

“You even represent the big Dawes bank that got the millions from the government when the ink was hardly dry on Dawes’ resignation as head of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, Mr. Mitchell?”

“Why, yes!” He was warming up. “And the whole World’s Fair is in my district.’ “And the great gum king’s building, the Wrigley building?”

“No,” he said sadly, “the Wrigley building is just outside my district.”

So these, the rich and mighty of business and finance, were the constituents Congressman Mitchell admitted he represents these, rather than the thousands of poor oppressed Negroes in his district! The atmosphere of these offices was as oppressively obsequious as that of a first-class saloon of a transatlantic steamer.

“How many Negroes are there in your district?” I asked Mitchell.

He didn’t know! When I persisted in asking for at least the percentage of Negroes, he said, “Oh, about half are Negroes.” His fair face bobbed in repeated bows. He added:

“You can see I couldn’t represent my race here any more than any other Congressman does. It’s not my fault if I happen to be colored.”

I checked him on the truth that he didn’t represent his race any more than any “other” Congressman (for obviously no politician speaks for the Negro in Congress). Apparently mistaking the statement of the fact for approval of it, he purred: “I’d be a mighty big fool talking about Negroes around here. Why, I got more than two white votes to one Negro vote. These are facts the public should know.” I agreed. Then Congressman Mitchell acknowledged the correctness of another quotation. He had said in an interview which appeared in The Washington Star:

“I don’t plan to spend my time fighting out the question of whether a Negro may eat his lunch at the Capitol or whether he may be shaved in the House Barber Shop. What I am interested in is to help this grand President of ours feed the hungry and clothe the naked and provide work for the idle of every race and creed over which floats the stars and stripes.”

Mitchell actually complained that old Oscar DePriest, his Republican predecessor, had been guilty of “arraying race against race.” The DePriest whose monument is a ritzy suburb which is blazoned to the tourists on the broad highway as a Jim-Crow development! The signboard reads: “DePriest Village For Colored.” The DePriest whose answer to Howard University students picketing the Jim-Crow House restaurant was to introduce a resolution for an “investigation”–and at the same time to apologize for the students’ action. The DePriest who is to the Republican wing of the ruling class what Jones is to the Democratic clique in power!

I ASKED Congressman Mitchell whether he hadn’t seen all of the many statements by government and semi-official bodies showing that the poverty of the Negro masses has increased sharply under the New Deal launched by the man he called “this grand President of ours.” I was thinking of the official reports cited recently by the Joint Committee on National Recovery, an instrument of Negro reformist groups. The Committee pointed to F.E.R.A. figures showing that registered unemployed and their dependents increased from 2,117,000 in October, 1933, to 3,500,000 in January, 1935. The Committee charged the A.A.A. with depriving 800,000, predominantly Negroes, of farm work. The Joint Committee was set up to combat deliberate discriminations against Negro workers which were written into the N.R.A. codes under the crude disguise of geographical differentials. For example, the code for the fertilizer industry, in which most of the employes are Negroes, established a North-South differential and proclaimed Delaware in the “southern” lower-wage bracket, while in other codes covering white-worker industries, geography was recognized and Delaware was set down properly among the northern states. In addition, the Negro worker has faced innumerable refusals to comply with even the meager wage and hour standards set, and of speed-up and stretch-out tactics. All to the accompaniment of always-higher prices of necessities. The degree to which Negroes have been forced to produce more for less compensation is indicated by a recent Federal Reserve Board’s report. It shows that in so typical a field of Negro labor as the tobacco industry, payrolls dropped 1.3 points on the index standard, employment dropped 2 points, during the period between November, 1933 and November, 1935, while production rose 50 points.

Congressman Mitchell didn’t give me chance to mention anything specific. He became legalistic and a trifle hostile, saying he hadn’t seen “all” the statements. Had he seen any, then? He dodged, “I think you can see anything you want to see in this great land of ours.”

“What do you see, Mr. Mitchell? What do you see as the effect of the New Deal upon the Negro people?”

“Oh, I have my own mind about that,” he replied. He was eyeing me with increasing suspicion. He slipped into the speech of his native Black Belt, adding, “I don’t know yo’ motives no way.”

I reminded him I had explained at the outset that I represented The Daily Worker and THE NEW MASSES. His secretary came in to tell him someone was waiting to see him. He told me, “There’s been no discrimination against me here. I eat in the House restaurant and take guests there. I’m shaved in the House Barber Shop.”

Mitchell even rides in Pullmans below the Mason-Dixon line, he explained. Years ago the general manager of the Southern Railroad assured him that Pullmans were “for gentlemen–educated, high-class men of either race.” High-class! “Why, Mr. Mitchell, do you approve of such distinctions between the upper class and the working class of both races?” His catlike eyes grew narrower. “I said educated,” he corrected, “and of course an educated man is capable of rendering greater service to society. Though I don’t think there should be any discrimination as far as human rights.”

“What are we talking about right now, if not about human rights?”

“This interview is over.” The Congressman stood up. “Someone is waiting to see me.”

“A moment ago you said something about my coming back later—?”

“No!” The word slid through his compressed lips. “No, I wouldn’t talk to you.” He moved to a side door and motioned to me. “You go right out this way. Why, for all I know you might be mixed up with those Communists!”

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1935/v15n08-may-21-1935-NM.pdf

PDF of full issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1935/v15n07-may-14-1935-NM.pdf