Eugene Gordon looks at Black portrayals in ‘serious’ theater from Uncle Tom’s Cabin of the 1850s to the left-wing stage of Stevedore in the 1930s; with a particular focus on the plays of Eugene O’Neill.

‘From “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” to “Stevedore”’ by Eugene Gordon from New Theatre. Vol. 2 No. 7. July, 1935.

EVER since the night Uncle Tom first shuffled upon the stage, American drama has emphasized the ruling class concept of the Negro’s place in this social order. It makes no difference that Uncle Tom and other “Negroes” often were whites smirking under burnt cork and groveling under kinky wigs; the idea of the Negro’s place was so emphatically implied that succeeding generations of colored actors have naturally assumed the stereotype.

The ruling class decreed the Negro’s place to be down below, in the spheres both of economics and of art, and permitted none but white men to personate the ruling class concept of the black man. Society cut the pattern for black-white relationship, slave-plantation mode of production, plotting the outline with blacks on the lowest level. Since men habituate themselves in all relationships according to their peculiar roles, enacting their parts automatically, the roles of master and slave bore a constant relation to each other.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin reflected ruling class opinion of the Negro’s place in bourgeois American life, although neither Harriet Beecher Stowe, who wrote the novel, nor Charles Townsend, who adapted the play, purposed it. The points of view of the South and the North were fundamentally identical: the Negro was definitely a being psychologically doomed to slavery forever. Uncle Tom’s Cabin reflected this viewpoint. For instance:

“ELIZA: Yes, down the river where they work you to death. Uncle Tom, I’m going to run away, and take Harry with me. Won’t you come too? You have a pass to come and go at any time.

TOM: No, no–I can’t leave Mars Shelby dat way. But I won’t say no to you’re goin’. But if sellin’ me can get mas’r outer trouble, why den let me be sold. I s’pose I can bar it as well as any one. Mas’r always found me on the spot…he always will. I never have broken trust, nor used my pass no ways contrary to my word, and never will. It’s better for me to go alone, than to break up the place and sell all. Mas’r ain’t to blame, and he’ll take care of my wife and little ‘uns!”

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s plan of attack on slavery was gradually to destroy it so that the ensuing hardships to the master would not be too great: reduce his property by removing a slave here and there, now and then, until all are freed. Uncle Tom falls in with the plan: better for him to go alone “than to break up the place and sell all.” “Mas’r ain’t to blame,” so be tender with him. It is the fault of the system. Mas’r is, in a way, as much a slave as Uncle Tom. This sentiment is implicit in that one passage. The whole play implies more.

Loyalty and devotion in general are the essence of nobility: a slave is noble if loyal and devoted. This is the lesson of Christianity. It is ruling class ideology; it is the message of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The author commends Uncle Tom for remaining with Mar’s Shelby. Speaking through the playwright, the ruling class commends all Negroes who are loyal and devoted to the white master class.

Tom was neither loyal nor devoted to his last owner, Legree. Why? Because Legree was not of the master class. He was an upstart, villainous poor white, deserving and receiving con- tempt. Slaves were taught loyalty and devotion to those God ordained to rule; this doctrine implied scorn for those hired to rule.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin reflects ruling class ideology from another angle. Tom’s second owner, St. Clare, is speaking to Maria, St. Clare’s wife: “I’ve brought you a coachman, at last, to order. tell you he is a regular hearse for blackness and sobriety,” and so on. The audience has already met George Harris and Eliza. Harris is a “pretty good- looking chap,” for he is “kind of tall,” has “brown hair” and “dark eyes”; in other words, George Harris is an octoroon. His wife, Eliza, is also “as white as you are,” Shelby tells Haley, the slave trader.

DOES all this detail about the physical appearance of Tom, Harris, and Eliza serve no purpose than to heighten dramatic interest? Hardly; but dramatic interest is heightened not only by showing that slavery’s leprous hands often fell on “whites,” but that “white” Negroes were given less than blacks to mumbling nonsense about loyalty and devotion. The “fullblooded” Negro, implies the author, is inferior to the Negro with “white” blood. Mixed bloods are portrayed as impatient of restraint, as if slave psychology is foreign to them alone.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin was the artistic expression of the industrial bourgeoisie on slavery. It was also the expression of the ruling class as a whole: roughly, the capitalists in the North and slave-holders in the South. It was the conviction of this class that it had a god-ordained right to be. The fundamental “right,” therefore, of one class to rule another was not the question at issue. The question was how to reconcile differences between the non-slaveholders and the slaveholders so as to unite the ruling class. Was Uncle Tom more effectively exploited by the wage slavery of the North or by the chattel slavery of the South? That was the question reconciliators must consider. The author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, however, was as unaware of her role of reconciliator as Paul Green or Eugene O’Neill is unaware today of assuming a traditional attitude toward, and repeating traditional slurs about, the Negro. The man who dramatized her novel similarly played his role.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin was one of the first instances “where an attempt is made to present to the American public in a realistic manner the authentic life of the Negro,” asserts Montgomery Gregory in his introduction to the plays in The New Negro. The other drama, he says, was Dion Boucicault’s Octoroon. Gregory thinks these plays “served to rationalize somewhat the stage conception of the Negro,” which, until now, had been the “darkey” of minstrelsy, “and accustomed the theatre-going public to the experience of seeing a number of Negro characters in other than the conventional ‘darkey’ roles.”

Gregory’s saying that Uncle Tom’s Cabin “served to rationalize somewhat the stage conception of the Negro” is correct. It was “somewhat,” in a most limited sense. Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Octoroon no more presented “in realistic manner the authentic life of the Negro” than the earlier minstrels had done. In minstrelsy, the slave was an irresponsible happy-go-lucky; in “serious” drama, he was a saint who had only to die to join the “authentic” angels. To the playwright whose interest lay with the South, the black man belonged forever in slavery; to the play-wright whose interests were one with the rising bourgeoisie, the Negro was capable of development as a free man. These playwrights agreed that in neither case should the black man be a member of the ruling class.

“The minstrel tradition continued until the middle nineties, when John W. Isham organized a musical show, The Octoroons,” declares Gregory. There followed a succession of musical comedies, the casts of which were completely Negro. The minstrel tradition did not end with the Negro’s writing and producing musical comedy, but continued in a more refined form. When the Negro produced for the first time in his own theatre he recognized and adhered to the stereotype–with trifling variations that the ruling class tradition had cast on the psychology of Americans.

The dialectical development of American drama dealing with the Negro reveals itself clearly. Uncle Tom’s Cabin, despite its capitalist bias, was anti-slave. To that extent it was an advance over all earlier plays concerning the Negro. Bringing the Negro on the stage with whites in Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Octoroon was a part of the general sympathetic treatment Negroes were to expect from liberals.

WE can appraise these various plays correctly only by taking each of them in relation both to its period and to American drama as a whole. When we look at American drama in this way we discover the significant position the Negro has held in it.

Used from the first as the cheapest possible labor and, later, after emancipation, as a threat to white labor whenever it rebelled against exploitation, the Negro, with his peculiar racial characteristics, has been a godsend to the ruling class. His racial characteristics are the identifying marks by which the “inferior” is distinguished from the “superior.” Therefore, they must be preserved. Jim Crow laws, laws forbidding intermarriage, slums to which Negro workers are confined, separate Christian churches these are some of the means of preserving the Negro’s identifying marks. The theatre is an especially valuable art form to the ruling class, due to the drama’s power to illustrate graphically the differences between whites and blacks.

The tradition of Negro inferiority and white superiority penetrates even such recent “realistic” plays as Ridgley Torrence’s Granny Maumee, The Rider of Dreams, and Simon the Cyrenian, Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones and All God’s Chillun Got Wings, Paul Green’s In Abraham’s Bosom, The No ‘Count Boy, and Roll, Sweet Chariot, Du Bose Heywood’s Porgy, and Ernest Howard Culbertson’s Goat Alley.

Negro workers who know the “stark realism” of, say, O’Neill’s, Green’s and Heywood’s plays look upon it not as the kind of realism the black man actually encounters, but as just another and a more “civilized” method of attack. It is only the upper class Negroes who accept the false fatalism of All God’s Chillun Got Wings, Roll, Sweet Chariot, and The Emperor Jones as true to Negro life. These people do not accept it because they believe it is “authentic,” but because, accepting the present social order as defender and preserver of their prerogatives of helping to exploit the black workers, they must defend the capitalist culture.

O’Neill’s, Green’s, and all other “liberal” writers’ plays about the Negro serve the capitalist class better than the old minstrels, while the older dramas=-for instance, Thomas Dixon’s The Clansman (from which the film, The Birth of a Nation was made)—with their uncompromising depiction of the Negro as sub-human, were crude in their elemental hatred beside the plays of today’s “friendly” playwrights. The very openness of The Clansman’s assault blunted its point, but the subtle calumny in All God’s Chillun Got Wings, and others in this category, makes these plays the more dangerous since their deadly influence is often fatal before it is observed. In All God’s Chillun Got Wings, O’Neill rears the white girl, Ella, and the Negro boy, Jim, together through childhood, rather honestly portraying their reactions to a hostile environment. They finally get married, but, instead of showing how a black man and his white wife may fight and win, the author prefers to show them in defeat. He even shows the Negro failing in his law examinations as if seeking further to prove his “natural” inferiority.

O’Neill must make Ella insane in order to keep her Jim’s wife, and O’Neill must add, when the white wife kisses her black husband’s hand (his hand, mind you!) “…as a child might, tenderly and gratefully.” Why should she not kiss him as a woman might, possessively and with passion? Because the Negro’s place is that of an inferior, especially in social relations, most emphatically inferior when a Negro man and white woman are socially involved. Even so, Ella must be made crazy before she kisses her man, so that the audience will realize her ignorance of what she is doing. All God’s Chillun Got Wings, The Emperor Jones, Roll, Sweet Chariot, Porgy, all these “serious” plays of Negro life succeed in doing what Gregory praised Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Octoroon for doing: “rationalize somewhat the stage conception of the Negro” and accustom “the theatre-going public to the experience of seeing a number of Negro characters in other than the conventional ‘darkey’ roles,” but they do not change the basic attitude toward the Negro.

Ruling class conception of the Negro worker is a “darkey,” regardless of his playing the minstrel Jim Crow or the tragic Emperor Jones. Although In Abraham’s Bosom is sympathetic, in Roll, Sweet Chariot, Paul Green refurbishes the Uncle Tom’s Cabin theme. John Henry, being black, cannot find “redemption” except through suffering on the chain gang. Happiness comes in heaven: it is reached only by way of the grave.

O’Neill’s treatment of the Negro is no better than Green’s, although O’Neill is a better artist. Ruling class tradition has so warped both their judgments that what they are doing is a sort of automatic writing, the hoary shade of Uncle Tom being the spirit which guides their hands. Brutus Jones achieves “great” heights, yet his pinnacle but touches the soles of Smither’s muddy and broken shoes. At the crest of Jones’ glory he is still inferior, at least in the social scale, to the cockney outcast. Look at the last lines of The Emperor Jones:

LEM: (calmly) Dey come bring him now. (The soldiers come out of the forest, carrying Jones’ limp body. He is dead. They carry him to Lem, who examines his body with great satisfaction.)

SMITHERS: (leans over his shoulder-in a tone of frightened awe.) Well, they did for yer right enough, Jonesey, me lad! Dead as a ‘erring! (Mockingly) Where’s yer ‘igh an mighty airs now, yer bloomin’ Majesty? (Then with a grin) Silver bullet! Gawd blimey, but yer died in the ‘eight o’ style, any❜ow!

Radical drama comes closest to being a dialectical representation of life because it shows the relation of black workers to the means of production, to class-conscious white workers, to the ruling class, to the upper class of their own race, and to all the other elements of society. John Wexley’s They Shall Not Die and Paul Peters’ and George Sklar’s Stevedore are the first clean breaks from tradition. These authors bring the Negro upon the stage as a genuine human being, showing him in his actual relation both to the productive forces and to the whites of his class. Their portrayals mark the difference between distortion gleaned from without and perception gained from within.

Alliances once unthinkable, alliances between white workers and black workers, have evolved from the changed relationships as shown in these plays. The dramas fall short of “socialist realism” to the extent that they fail to integrate these various relationships. Both They Shall Not Die and Stevedore are less than first rate plays simply because they do not truthfully show the interplay of all the elements these dramas represent. They Shall Not Die, for instance, is untruthful in slurring over the potency of mass pressure upon the courts of so-called justice. The defence lawyer becomes the “hero,” whereas the real “hero” is nothing less than the international proletariat, with its weapon of organized mass pressure.

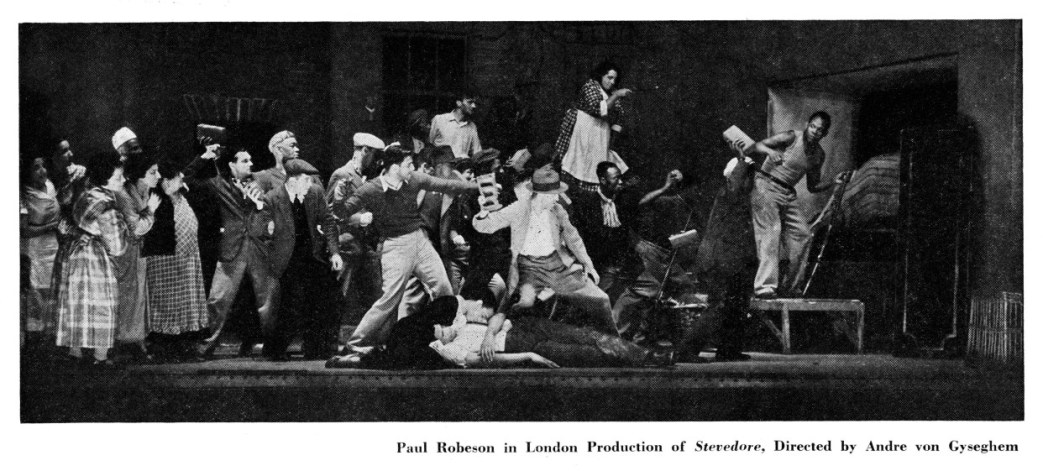

Stevedore is better than They Shall Not Die because it is dialectically better constructed. It is truer to the life of workers today, when whites and blacks are coming to recognize their common interests, when they are seeing that they all are oppressed by the identical forces of capitalist society in decay and that the oppressors the various agencies of decaying capitalism–are the common enemy of black and white workers.

Stevedore‘s conspicuous departure from “socialist realism” occurs in the staging of Scene I, Act III. Negroes do not sing hymns around their dead at a wake. One feels that this scene is meant to catch the fancy of the upper class, which “adores” the Negro’s spirituals. It seems like another form of bowing to tradition; another way of linking the Negro actor of today with the Uncle Tom tradition.

The interval between Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Stevedore marks the difference between a Negro who servilely bowed himself into his place beneath the whites and the one who militantly takes his place beside his white fellow worker. Plays like They Shall Not Die and Stevedore are effective weapons against those innumerable economic and cultural differences which will persist for the black man until we destroy the last vestige of slavery.

The New Theatre continued Workers Theatre. Workers Theatre began in New York City in 1931 as the publication of The Workers Laboratory Theatre collective, an agitprop group associated with Workers International Relief, becoming the League of Workers Theaters, section of the International Union of Revolutionary Theatre of the Comintern. The rough production values of the first years were replaced by a color magazine as it became primarily associated with the New Theatre. It contains a wealth of left cultural history and ideas. Published roughly monthly were Workers Theater from April 1931-July/Aug 1933, New Theatre from Sept/Oct 1933-November 1937, New Theater and Film from April and March of 1937, (only two issues).

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v2n07-jul-1935-New-Theatre.pdf