Foster arrives in Paris and can’t resist the tourist urge to see the Louvre and Bastille.

‘In France’ by William Z. Foster from Industrial Worker. Vol. 2 No. 26. September 17, 1910.

Paris, Aug. 28, ’10.

Fellow Worker and Friend:

I arrived here ten days ago, but I have been so very busy that I haven’t taken time to write to anyone. Now that I am getting settled down, you may look for a letter from me every week or so.

The country between Cherbourg and Paris is as pleasing as it has ever been my lot to see. In Normandie, between Cain and Cherbourg, the country is particularly fine, and the wide, flat fields are in a state of cultivation entirely unknown in America, except in cases of isolated Japanese or Chinese truck gardens, or some show farms. It was harvest time when I passed through the country, and the primitive methods of harvesting struck me almost with a shock. The old-fashioned cradle scythe is almost universally, used, although here and there our good revolutionary friend, the American binder, was in evidence. The crude French farmers, in handling the grain, tease, caress and fondle it, putting it through the most elaborate and fantastic processes before it finally becomes marketable. How they ever can expect any “surplus value” from the “labor power” is mystery to me, one who is accustomed to the slap-bang methods of the Palouse and other bonanza American wheat districts.

There is one feature of the Norman country that particularly impressed me. It is the method of housing the population. In the States we are accustomed to seeing a house on every farm, but it is not so in Normandie. There, one may travel for miles along the railroad, through a country in the highest state of cultivation, and yet never see house, although the farms undoubtedly belong to small proprietors.

The reason for this is that Normandie was populated long before the railroads came, and these usually powerful population distributing agencies had nothing to do with the formation of the settlements. Their character was determined by the condition of the Middle Ages, so the people live in small villages, as they were once forced to do for mutual protection. These towns and villages are not necessarily near the railroads, except where the road was built to them. The field of Normandie were once farmed collectively from these villages or commune centers, and they present a very strong contrast to the individualist’ farms of America and other more recently settled countries.

Arriving at Paris, one of the first things I did was to hunt up the Bourse du Travil and make myself acquainted. This was not so easy a task as one might imagine, as I understand very little French, and the natives understand less English. However, I finally located the C.G.T. interpreter, and after my assuring him that I was in no way connected with the “Gompers bunch” he gave me a hearty welcome.

As I do not understand much French, I but dimly comprehend the situation here, and will not for a month or two; by which time, however, I hope to understand enough French to know what is going on. Even though the details are very much obscured to me, there are some things going on here that I cannot help but understand. One of these is that the C.G.T. is doing things. All over Paris on every wall are flaming syndicalist posters, calling on the proletariat to unite, giving notices of strikes, lockouts, etc. Even I can detect that these posters are couched in real working class terms of revolt. The effect of these posters, thus widely advertising the activities and the fundamental principles of the revolutionary element of the working class, must be for reaching. It seems to me that the I.W.W. could adopt this method of publicity much more extensively, to very good advantage, even if it necessitated the cutting down of the pink allowance of our too often ornamental speakers.

My impressions of the Syndicalist movement are as yet necessarily very raw, and I will not attempt to air them now, but will wait until they are a little better formed. However, it seems very evident from the activity here that the American labor movement is in its swaddling clothes.

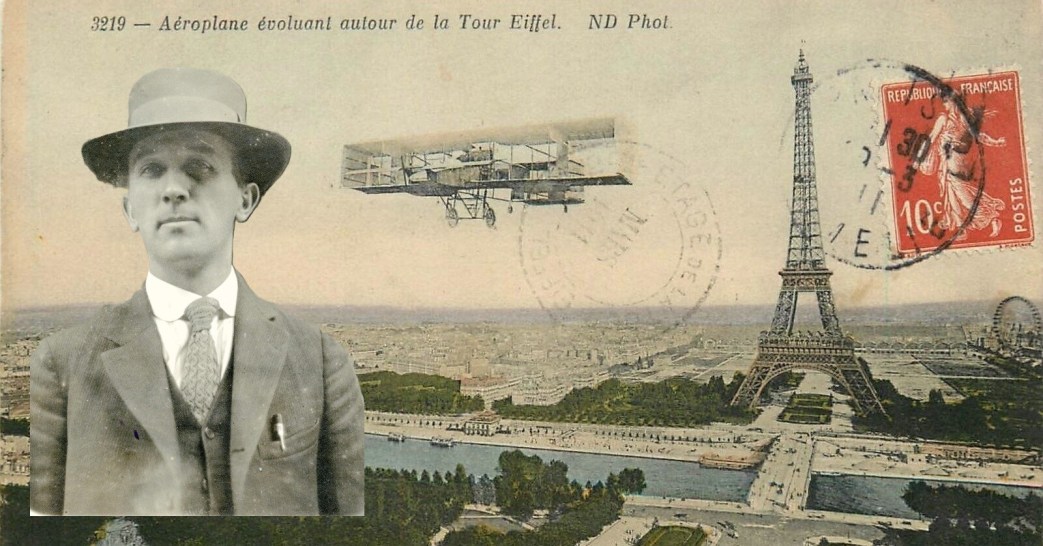

Though I did not come to France to “see the sights,” I could I could not resist the temptation of paying a visit to some of the famous places in Paris that I had heard and read so much about.

The “Place du la Bastille” is a meaning term to all rebels who have read anything at all, and when I started toward that historic spot I was full of anticipation but the alleged monument now occupying the site of the prison is very unsuggestive, and I retired disappointed.

The “Palais du Louvre,” which figured so prominently in the French Revolution, was not so disappointing. It is a vast structure covering several acres in extent and though it is not startling in architectural beauty, it compels a certain amount of admiration by its great size and its history. About half of this building is now used as a museum–the equal of which perhaps does not exist in the world. The best feature of the museum is the great collection of paintings. There are miles of them by the most famous painters who ever lived. They represent millions of dollars. Works by such painters as Titian. Rubens, Van Dyke. Murillo, Rembrant, Reynolds, etc., are on every hand, and there are so many of them and they are so poorly arranged that one gets tired looking at them. They are arranged in the usual gingerbread fashion, big and little together, heterogenous mass. There is one bright oasis in this flaming, discord of paintings, however, and that is a large hall that is devoted entirely to the works of Rubens. There are about 25 historic masterpieces, all of one size, artistically arranged, and they make a picture one will never forget.

LATER. I have just returned from seeing big fire where about $100,000 worth of the master’s property went up in smoke. The whole affair was a sort of opera bouffe, and very amusing. The fire apparatus arrived at the scene in good time and after a half hour’s unintelligible squabbling they finally got a few feet of garden hose into play and the surrounding property saved. Meanwhile, pandemonium reigned in the street. No attempt was made to establish fire lines and the crowd wandered whither it would. The notorious Parisian “Apaches” were careful not to let the opportunity slip and reaped bountiful harvest in the crowd. Several were arrested for stealing from surrounding buildings from which the goods were being taken. After about an hour of this chaos、 a company of soldiers arrived and charged the crowd, effectively cleaning the street. I couldn’t help but think of how the N.Y. Bremen or the Spokane police would have handled that crowd with streams of water. Here the slaves are not so submissive as they are in the States, however, and might get into action in the event of such tactics being used on them.

Yours for the I.W.W.

W. Z. FOSTER, Hotel du Lilas, Rue Lauzin.

The Industrial Union Bulletin, and the Industrial Worker were newspapers published by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) from 1907 until 1913. First printed in Joliet, Illinois, IUB incorporated The Voice of Labor, the newspaper of the American Labor Union which had joined the IWW, and another IWW affiliate, International Metal Worker.The Trautmann-DeLeon faction issued its weekly from March 1907. Soon after, De Leon would be expelled and Trautmann would continue IUB until March 1909. It was edited by A. S. Edwards. 1909, production moved to Spokane, Washington and became The Industrial Worker, “the voice of revolutionary industrial unionism.”

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/industrialworker/iw/v2n26-w78-sep-17-1910-IW.pdf