Dante and James Joyce are invoked as the poet Delmore Schwartz takes issue with ideas in Meyer Schapiro’s monumental essay, ‘Nature of Abstract Art’, who responds in this rich discussion from the short-lived Marxist Quarterly.

‘On the Nature of Art’ by Delmore Schwartz and Meyer Schapiro from Marxist Quarterly. 1 No. 2. April-June, 1937.

I. DELMORE SCHWARTZ

IN the first issue of the Marxist Quarterly, Meyer Schapiro provides ample I evidence of the social basis of abstract art. It is difficult to see how the thesis which he opposes, the doctrine that art can be purely formal, can withstand his array of “correlations.” But his own doctrine itself suggests very difficult questions, of which Schapiro may be very much aware. When we see him finding a social fact for every pictorial element, no question seems more relevant than this one: How is any social product less expressive of social facts than a work of art? That is to say, would Schapiro be able to see the same social facts in such objects as a pulp novel, a bank and a newspaper? Each of these is itself a work of art in some sense, but on the contrary, we also seem to find them somehow different from works of art “proper.” The question concerns the line we draw; how could Schapiro justify the difference, or is it justifiable?

The simple answer might be just this: that an authentic work of art is better expressive and more expressive. It is so precisely because it is the product of a sensitive individual working in a medium which provides a wide range for perceptions and emotions. And again, it might be said that the medium of a great art like painting brings to an explicit surface values and motivations which are disguised in other social products. But here again there are difficulties. One remembers that the artist may be considered a special and complicated soul, not typical of the time. It might seem that the movie, because its appeal is so much more widespread, is much more expressive of the character of society than a picture of Picasso’s. Furthermore, the movie may express in broader and clearer outline the social fact in question, especially to one with so keen an historical sense as Schapiro. So far as the explicit surface of good art is concerned, clearly there are many ways of being explicit, some of which are surely more likely in a factory or an automobile. What need, then, is there for the painting? Would Schapiro be unable to find any of his social facts exhibited elsewhere?

Obviously, Schapiro will have to say that the great work of art contains something which is lacking in other social products. It might be said that in his article he was merely concerned with displaying the social basis of abstract art, but on the other hand his article is entitled “Nature of Abstract Art.” Suppose, then, we assume that Schapiro’s method is based upon the doctrine that art is expression. It is the vagueness of the term “expression” which is at fault. We can say that the worn glove expresses the shape of the hand which has worn it, and we can also say that a burnt matchstick is expressive of the character of our society. If expression is taken to mean “reflecting,” “mirroring,” “reproducing,” then, as has just been noted, there will be the difficult question about which social products are the best mirrors. But Schapiro seems to hold a more complicated view of what is contained in the work of art. In the following passage, which would seem to be an excellent example of what he does, he says:

“Early Impressionism, too, had a moral aspect. In its unconventionalized, unregulated vision, in its discovery of a constantly changing phenomenal outdoor world of which the shapes depended on the momentary position of the casual or mobile observer, there was an implicit criticism of symbolic social and domestic formalities, or at least a norm opposed to these. It is remarkable how many pictures we have in early Impressionism of informal and spontaneous sociability, of breakfasts, picnics, promenades, boating trips, holidays and vacation travel. These urban idylls not only present the objective forms of bourgeois recreation in the 1860’s and 1870’s; they also reflect in the very choice of subjects and in the new esthetic devices the conception of art as solely a field of individual enjoyment, without reference to ideas and motives, and they presuppose the cultivation of these pleasures as the highest field of freedom for an enlightened bourgeois detached from the official beliefs of his class. In enjoying realistic pictures of his surroundings as a spectacle of traffic and changing atmospheres, the cultivated rentier was experiencing in its phenomenal aspect that mobility of the environment, the market and of industry, to which he owed his freedom. And in the new Impressionist techniques which broke things up into finely discriminated points of color, as well as in the ‘accidental’ momentary vision, he found, in a degree hitherto unknown in art, conditions of sensibility closely related to those of the urban promenader and the refined consumer of luxury goods.”

The italics in this passage are, I need hardly say, my own. The italicized words not only display the ambiguity of speaking of expression: they also show how complicated and how inexplicit is Schapiro’s notion of what is to be found in a picture. In the paintings of the Impressionists, he finds a moral resolution, an implicit criticism and a norm. These, as well as many aspects of contemporary life, are presented, reflected, presupposed, found and enjoyed. Now we can say that what we get in a picture is a reaction to social facts; and this will take the form of criticism which is implicit, or a norm. Or we can say that what we get is the social fact, part of which may be the reaction to other social facts. Or we can say that we get both, in an indivisible compound. If we take the latter two alternatives, we remain without a basis for saying that painting is somehow superior to the comic-strip (for, to repeat, both spring from the same social basis). What interests me is the first alternative; and it is only, I think, by investigating the first alternative that we can explain Schapiro’s reference to the enjoyment of the cultivated rentier. What we have to explain is this enjoyment, as well as the difference, in expressive character, between a good work of art and other social products. And the enjoyment may lead us to the expressive difference.

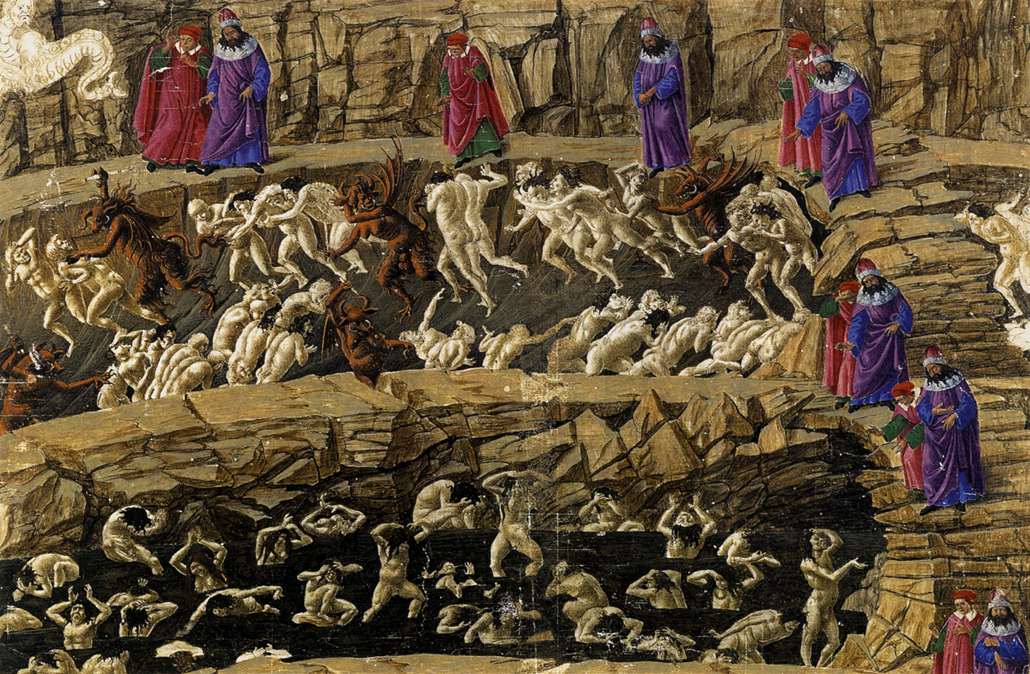

Imitation, in its most literal sense, would seem to be an irreducible element in the artistic act and the artistic product. We say: How true to life this book is! how profound! what insight! his characters are living! and these statements, crude as they are, make clear the imitative truth which is one of the things which we look for and which we find in the work of art. And there is a literal example of the sense in which a work of art 1s imitative. If one looks in the mirror, and only if one does, can one see what one’s face looks like. Just so, the medium acting as a mirror, we can say that we find out what our perceptions, emotions and values look like in the various looking-glasses of paints or tones or words. And just as we can only see our face in the looking-glass, and in no other way, so we may say that some things can only be presented by means of one medium or another. Thus we may say that a work of art can be true and can be one kind of knowledge. What we get as truth in The Divine Comedy is not the doctrinal truth of Thomism, but the way the world looked to a medieval Thomist. Such a notion of the nature of art settles immediately the problem of belief in art: what we get is: what-it-is-to-hold-such-a-belief.

Now this expansion of the doctrine of imitation would seem to explain a good deal and to be one part of the truth. But it brings up the same difficulties as the more modern notion of expression (from which it probably does not differ very greatly). For the best imitation would be the best art, and we would probably have to say that James Farrell is a better writer than James Joyce (since the former is the more consistent reporter).

It is when we analyze out such an example as this, Farrell against Joyce, that we come upon a notion which will explain and clarify Schapiro’s different attributions, presentation, discovery, criticism, enjoyment, etc. We have to say that Joyce is preferred to Farrell (or the converse, since dispute is perhaps conceivable) because the one introduces into his imitative perceptions an element of judgment or criticism or value, which is lacking in the other. Now it is possible, and it is important, to distinguish carefully between the expression of a social fact, and, on the other hand, a reaction to social facts which is made in the very act, and by means of, composition. There is a difference, for example, in describing a murder and including in your description the various attitudes, perceptions and judgments of the persons involved, and, on the other hand, in describing the murder in such a way that the values which you, the narrator, hold are focused upon the facts of the description. Both descriptions will contain some element of valuation; but the second one will be a deliberate act of valuation. Thus, to shift to more extreme examples, a burnt matchstick or an auto-mobile will both be expressive of social facts and social values. But a lyric poem or a painting will be expressive of a reacting valuation of social facts and social values. That is why the painting will be more interesting and more significant, as a presentation, than the automobile or the bank. The distinction is one of degree, but there are many degrees, going from the mere reflex of values to be found in an advertising poster, through the more partial and less typical reaction to be found in a newspaper editorial, and ending in the highly special, actively critical valuing, accepting and rejecting of social facts which is to be found in the works of a great painter, and which Schapiro is probably best equipped to describe.

Indeed, there is much in what Schapiro says which would suggest this distinction between what may be called the expressive and the critical-expressive. He says: “There is no passive ‘photographic’ representation…the scientific elements of representation in older art—perspective, anatomy, light-and-shade—are ordering principles and expressive means as well as devices of rendering. All renderings of objects, no matter how exact they seem, even photographs, proceed from values, methods, and viewpoints which somehow shape the image and often determine its contents.” It is quite clear that Schapiro believes that the expression of value is one of the most notable aspects of the work of art. But this is attributed even to photography, and the differences in degree are not explicitly stated, although, again and again, what Schapiro finds in his examples—and would not find elsewhere—is precisely the expression of an act of valuation upon the part of the artist, and focused upon social facts: “By a remarkable process the arts of subjugated backward peoples, discovered by Europeans in conquering the world, became esthetic norms to those who renounced it.”

On the other hand, Schapiro indiscriminately brings in other functions: “This new responsiveness to primitive art was evidently more than esthetic: a whole complex of longings, moral values and broad conceptions of life were fulfilled in it.” And this notion of the fulfillment or satisfaction of values in a work of art is repeatedly stated; while, besides this, there is in art merely the continuation on another level of activities, motives and satisfactions to be found in the social basis of the art: “It is, in fact, a part of the popular attraction of Van Gogh and Gauguin that their work incorporates (and with a far greater energy and formal coherence than the works of other artists) evident longings, tensions and values which are shared today by thousands who in one way or another have experienced the same conflicts as these artists.”

It is to be noted that a fourth element—and there are more—is introduced in passing, namely, energy and formal coherence. Perhaps this is the way that Schapiro would distinguish between the expressiveness of different social products: the painting has more energy and formal coherence than the comic strip. But on the one hand, it may not have more energy; on the other hand, by making such criteria the distinguishing factor, the door is opened to the purists and the formalists once more.

There is no question of eliminating or oversimplifying the complexity of elements, functions and services which Schapiro attributes to the work of art. The point is that these elements cannot all be of the same importance. The paintings of Van Gogh may afford a vicarious satisfaction to the thousands who have experienced the same conflicts. Impressionist paintings may reflect the mobility of the market and industry. The fashion of primitive art may express a reaction to imperialist expansion. Nevertheless, it seems likely that art is given such enormous attention because it contains some other element, not so readily available in other social contexts. This element, as I have already proposed, is the critical-evaluating focus which the artist directs upon his perceptions. And it must be insisted that this focus is interesting and significant only because it represents a new and individual reaction and response to social facts. Undoubtedly the focus itself is derived from some social basis; but if the artist is important, the focus will be literally an imaginative choice among the several alternatives which the social basis suggests.

There is no room to demonstrate at length that this focus is most immediately the artist’s style and the forms which the artist adopts. Schapiro provides several fine examples: the Renaissance artists, he points out, embody an idealization of the human body by “artistic ideals of energy and massiveness of form…even the canons of proportion, which seem to submit the human form to a mysticism of number, create purely secular standards of perfection.”

But I want to limit myself to the example in which the focus is, so to speak, self-conscious. We find in literature that there is a disinterested observer of the action, a chorus which comments upon the action, a friend of the family, the I of the story. Or we find that the story is in the form of a diary, or a series of letters, or, as in The Waves of Mrs. Woolf, the story is told by means of soliloquies; or the action is to be discerned in a “stream of consciousness.” All of these formal devices, chorus or diary or disinterested observer, are means of getting the critical-evaluating intelligence into the action—but not in the action. In most works of art this factor is naturally less explicit, most frequently not explicit at all. But it is there, ordering the characters in terms of good and evil, distorting the usual look of natural objects, and sometimes showing itself in fantastic arrangements, far-fetched metaphors, and unheard-of chords. As a focus of values, it is significant only when it pervades social actualities—the artist, that is to say, must be a good imitator—but it is the imitation pervaded by the imagination of value, which is something not to be found elsewhere. It hardly seems necessary to repeat the Aristotelian dictum that poetry is something more philosophic than history—and archaeology—and that the dramatist is sometimes concerned with men as they ought to be.

There is thus a clear sense in which the work of art is an assertion of values—of values focused upon actualities, values distinct from the values which permeate the actualities. The sense in which an artist can be a propagandist is clear, although there is still the question of how consciously the focus of values which are expressed can be chosen. In this light, the significance of a work of art such as The Divine Comedy is still: what-it-is—in specific experience— to-have-such-and-such-beliefs-and-values (thus, in a way, we learn the consequences, in actual experience, of certain beliefs and values, which, taken on the theoretical level, might appear quite differently). Whether there is a further criterion whereby we judge the focus of values which informs and integrates the work of art in terms of our own values is a separate question. It seems likely that this further criterion is unavoidable.

All of this may merely be a refinement, in more abstract terms, of Schapiro’s doctrine; or it may not be. There are several passages which I want to quote as a conclusion. There is Hamlet’s address to the players on the nature of art: “the purpose of playing…both at the first and now, was and is, to hold, as ’twere, the mirror up to nature; to show virtue her own feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure.” From this, it is but one step to the doctrine of Matthew Arnold that poetry is the criticism of life. The two notions can then be seen together in Joyce’s Portrait of The Artist: “Welcome, O life! I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.”

Mirror, virtue’s feature, criticism, the reality of experience and the uncreated conscience: it would seem that it is by separating these in discourse and seeing them together in the work of art that we can understand the pleasure and illumination which art affords us, as well as its importance in history and society.

II. MEYER SCHAPIRO

The nature of art in general was not directly in question in my article, but the view common among writers and painters, that abstract art is released from historical contexts and society and is self-governed according to eternal laws of form. Whereas I tried to show how the abstract styles are conditioned by values and modes of thinking originating in a given historical society, Delmore Schwartz goes much further and concludes that the distinctiveness of art as such, whether modern or ancient, whether painting or literature, is to be found in the deliberate criticism and evaluation of social facts focused in a special medium by the individual artist.

Before I comment on this theory, I must correct some of the views imputed to me. I did not, as Schwartz says, try to find a social fact for every pictorial element. Nor would I see the same social facts in a “pulp novel, a bank and a newspaper,” or agree that the comic strip and abstract painting have the same social origins, though their causes may intersect. The difference does not lie simply in the greater or lesser expressiveness of certain of these fields, but in objective character of the media of the arts and in their functions, which are also subject to historical change. I was not concerned with social facts in general, for which I had to find the expressions or the symptomatic objects, but with the social facts relevant to modern painting, an historical field which had been described and evaluated as independent of social history. The same facts would not be relevant (at least, not in the same way) to the pulp novel, the bank and the newspaper. They might also be irrelevant to architecture, which had its special conditions and functions. Finally, my reference to certain artists as representing, reflecting, choosing, valuing and designing is no more an ambiguity of statement than Schwartz’s concluding summary of art in general as “mirror, virtue’s feature, criticism, the reality of experience and the uncreated conscience.”

His own view seems to me inadequate in two respects. In the first place, he absolutizes a peculiarity, or better, an ideal of modern literature as an inherent, universal character of art. Secondly, in distinguishing the focus from the content or the values focused, he detaches the form of the work—which he has identified with the focus—from the artist’s values, and thereby makes the form an altogether independent or merely intermediate factor. In describing the process of creation as deliberately critical of social facts, he inclines toward a moralistic-intellectual view of art, which often entails a neglect of esthetic qualities.

Far from being an inherent principle of art, the deliberate, individual criticism and evaluation of social facts, the distinction of the social values of the artist from the values in the world he depicts, is a recently acquired function, and even in modern times does not appear in all the arts. It is a particular historical content which presupposes not only a secularized culture, but also the self-consciousness that in making a work of art, the artist is coming to grips with the world, is asserting himself as over against society, and perfecting his own nature as a human being by independently posing and resolving momentous problems of life.

Such a view can hardly be attributed to most religious art in the past. There the artist’s critical reaction to his imposed subject matter is relatively unimportant beside the execution of fixed tasks. Even a work of great independence, like Dante’s, still moves within a sphere of official doctrine and religious lore. He may include his private judgment of individuals and affairs, but the poem as a whole was not conceived or constituted in that sense; it was not a deliberate, personal revaluation of experience, although the elements of such an attitude are present.

The very existence of the arts of music, of architecture and the industrial arts, which do not represent nature and therefore cannot refer in a definite way to objects of experience beyond themselves, must also limit this view. For how can we speak of a deliberate evaluation of experience in works in which the objects criticized do not appear and the values substituted are not explicit? Abstraction may be the result of a view of life, but the expression of this view is not necessarily the purpose of the picture. In fact, the view may never be present to the artist as a formulated judgment; it may simply be implicit in his practice and style. But where art is directly a representation, the criticism of life may also be only implicit. And even where there is an overt judgment, the criticism will often appear less in the sententious, deliberately announced judgments than in the implications for us of the objects and events described, and of qualities of the work perceived in relation to the possibilities of our own lives. In the statement quoted from Joyce there is a program which is more comprehensive than his actual work, but also less impressive than the smaller, but richer, reality of his “artist’s conscience,” implicit throughout the book.

As our own art becomes more concerned with the criticism of life, the art of the past is read accordingly, and the implicit values, the traces of social affairs, and of reactions to everyday experience in the older works become increasingly evident to our newly sharpened sight. But to transform these into the conscious objective of past art, to make these traces and implicit factors the deliberate content of the art is to misread the works.

The difficulty in attributing a conscious evaluating function to all art may be illustrated by an example from the middle ages. In the paintings of the thirteenth century the Gothic churches are represented without the amplitude, the spatial complexity and the light that we experience in their interiors—qualities that no doubt were foreseen by the builders. Instead the buildings are shown without depth, as small, flat objects, not much larger than the individuals beside them. The focusing element—to use Schwartz’s term—in medieval paintings of buildings does not permit us to infer the artist’s individual reaction to the cathedral; this is evident even in the drawings of architects. Their professional pictorial language had no terms for expressing these everyday perceptions. The painter’s private evaluation of the building as an object of his environment was not one of the functions of medieval art, in which the environment of things was a secondary matter. He represents the building not according to his appreciation of its qualities, but according to the impersonal conventions of his art which subordinate the building to the religious personages. These conventions were probably related in their origin to some aspects of the cathedral itself yet they make it impossible for the artist to present qualities of the building actually described in the literature of the time. The conventions were a method of symbolization based on a peculiar view of man and nature, common in the middle ages; they can therefore also be regarded as evaluating or critical in a broader metaphorical sense. But the fact remains that they preclude the statement of individual reactions to the objects represented. Such reactions were not a matter for painting at that time; the representation of medieval buildings as objects of esthetic contemplation is rare before the period in which religion declines. Hence to infer from the medieval images of cathedrals that the artist appreciated in the original building only a few surface elements, that his values as an individual excluded a view of other aspects, would be false. Similarly, to suppose that this imagery is a criticism of the architecture, a posing of the artist’s ideal as over against the actual object, would be absurd. The interpreter or critic of these arts has to discover their particular conventions and purposes before he can grasp the character of the values behind them.

In modern art—and especially in literature—where the representation may be a freely conceived individual view of things, Schwartz’s definition becomes more pertinent. It is not only a description of the nature of art, but also the statement of an ideal in terms of which he distinguishes greater from lesser art. But the relation of the elements of his definition—the artist’s values, the social facts, the focus—to the value of the work of art is not made clear. Is Joyce superior as a novelist because he has values and others have not? or because his social values are better than those of other writers? or is it finally because of the qualities of presentation, Joyce having a better “focus,” i.e. a style or form, superior to the focus of others? Do we read Dante to-day because we share his values, or because we enjoy the qualities of his imagination and his poetic vigor, the flexibility of his perceptions within a rigidly schematized world? Judged by his religious views and philosophy, Dante could not interest us much, except as an historical document; and this was indeed the attitude of writers of the eighteenth century. Considered practically, however, from the viewpoint of production, the poetic qualities are finally inseparable from Dante’s values and subject matter; he could not have created such a poem unless he had, among other things, this comprehensive view, an ordered religious world, and his secular qualities as a Florentine burgher. And even our judgment of the abstracted poetry of his work constantly presupposes our sympathy with his view of human nature, and also our capacity to re-imagine the feelings and actions he describes.

In admitting that it is necessary to find criteria to judge the integrating focus which judges the objects, Schwartz seems to isolate a non-ethical peculiarity of art, in the sense of the formalists. This concept of focus is metaphorical and somewhat obscure (perhaps because of the necessary brevity of statement). It designates not only the activity of concentration, but also the medium; it is used in a third sense as well, as the product of the interplay of the medium, the artist’s values and the process of creation, since the focus is finally revealed as the form of the work. At any rate, it is unclear whether the focus is the cause of the integration of the work or is that integration itself. And since the form is also expressive, bearing evident traces of the artist’s values and mind, the distinction between the critical values and the focus becomes even more uncertain.

To avoid the dangers of formalism, he seems to limit the form to an intermediary function; it is simply the power of focus, the strategy of presentation of more serious values. It is like the lines and columns in the ledger, the framework for orderly computation and balancing of receipts (the social facts) and expenditures (the artist’s values). Yet this focus remains finally the distinguishing aspect of art, since there are other fields of criticism and evaluation.

If focusing is simply the private imagination through which individual values are trained on the social facts, art is not different from the social sciences, or from ethical analysis; for science and moral reflection, in fact, any activity that refers to values, have an imaginative part, affected by the personality of the being in question. From another viewpoint it might be said that compared with logically made criticisms, the evaluation of life within a work of art is relatively unfocussed. The work of art is more focused with regard to the perception of the qualities of things and of its medium, less with regard to the possibility of a deliberate judgment of its represented object. We may even forget the latter, as we do before exotic religious works, and yet feel the greatest satisfaction before the qualities of the imagery.

When art is viewed as primarily a criticism of life, another focus is neglected, the professional consciousness of the artist. An artist begins by having to make, by a given technique, either for himself or at the command of others, a kind of object—a poem, a picture, a story or a building—very specific and traditional, with well known properties and its own conditions of perfection. This activity is itself a satisfaction and a personal value which already gives some direction to the work, though it is affected more massively by tasks imposed by an institution or by social functions of the art and by necessities arising from the artist’s life. Whether the artist is consciously evaluating an independently selected material or making an icon, his unconscious disposition, his energy of imagination, his skill and sensitivity, all shape the final result.

Marxist Quarterly was published by the American Marxist Association with Lewis Corey (Louis C. Fraina) as managing editor and sought to create a serious non-Communist Party discussion vehicle with long-form analytical content. Only lasting three issues during 1937.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/marxism-today_april-june-1937_1_2/marxism-today_april-june-1937_1_2.pdf