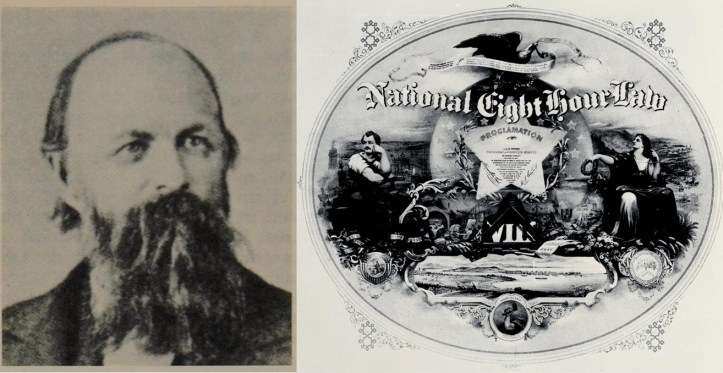

In the wave of Northern workers’ radicalism that accompanied Reconstruction in the South, one of the most important figures to emerge was the indefatigable fighter for the eight-hour day, Boston’s Ira Steward. A pioneer of U.S. labor too little remembered today, nevertheless whose contributions to the course of labor’s struggle for emancipation in this country are incalculable.

‘The Life and Work of Ira Steward’ by William Edlin from The Comrade. Vol. 1 No. 3. December, 1901.

Massachusetts is said to have enacted in her legislative halls the best and most favorable labor laws in the United States. In fact this is the common boast of the present-day politicians, of the great commonwealth; and, with important modifications, there is truth in the assertion. The leading State of famous New England can, indeed, show on her statute books a series of well-devised laws favorable to labor; and to no other man is due as much praise for influencing those laws as to Ira Steward.

During the two decades beginning with the War of Secession (1860-1880) the labor movement in this country had taken a long step forward. The number of labor leaders, many of undoubted talent and importance, that came into sight soon after the close of the Civil War was comparatively large. But without doubt no man has wielded such influence in favor of the betterment of the conditions of labor, and commanded as much respect for integrity of character and sincerity of purpose as the machinist, Ira Steward.

Being a workingman, who had himself well educated, possessing a rare intellect and keen powers of observation, with unlimited perseverance as a propelling motor, it was not at all difficult for Ira Steward to attain the high position that he held for many years in the ranks of progressive workmen. From his very early years he was intensely and actively interested in all questions that agitated the country, but never without a purpose. He always had in mind the labor movement. As a workingman he felt instinctively that his own life was inseparable from that of his class. The best years of his life were devoted to the cause he loved dearly, the amelioration of the condition of those whom we call wage slaves.

Ira Steward was an eloquent speaker as well as a brilliant writer. It cannot be said that he was thoroughly class-conscious, as the Socialists of the present day are. His historical knowledge did not go far enough to enable him to see the futility of relying upon the upper classes to bring about improved conditions for the workingmen. Much of his time and effort were wasted in appealing to capitalist philanthropists and politicians for aid. But he nevertheless achieved much. His influence in favor of labor was felt for many years, not only in the legislature of the State of Massachusetts, but also in Congress, at Washington, through such representatives of the commonwealth as Charles Sumner, Henry Wilson, Banks and others.

The life purpose of Ira Steward was to bring about the realization of a universal eight-hour working day. Clear it is that this was not his goal. His active life gives abundant proof to the contrary. The eight-hour working day was to him only a first step to the entire abolition of the wage system, the entire dissolution of the capitalist class and the establishment of co-operation.

As early as 1863 we find Ira Steward as a delegate in Boston at a convention of the International Union of Machinists and Blacksmiths of North America, where he introduced a resolution declaring that the most vital question to labor throughout the United States was the permanent restriction of the working day to eight hours. In the same resolution, which was adopted unanimously,

Steward embodied the great truth, then not generally recognized, that a longer working day meant usually lower wages and that a shorter working day meant higher wages to the toiling masses. A separate clause provided for the creation of a fund with which to carry on the agitation for an eight-hour day.

From that convention dates the almost unceasing activity of Ira Steward in favor of labor legislation. The agitation fund was started by the International Union of Machinists and Black smiths with a donation of $400.00; it was soon after increased by a like amount from the Boston Trades Assembly. Ira Steward rushed into print at once–pamphleteering and contributing articles to labor papers and all other papers that were willing to open their columns to him. He also took to the stump, lecturing before all kinds of audiences always on the same subject, with ever new arguments. He worked with a will. His heart and soul were in his agitation. From 1864 to 1870 every session of the Massachusetts General Court had to face the zealous apostle of a shorter working day, who appeared invariably before legislative committees, pleading for one labor measure or another. His earnestness, persistency and eloquence attracted the attention of many well-meaning, philanthropically-inclined persons of all classes. It did not take him very long to gather a small following of men and women who had considerable influence in political and educational circles.

Great was the joy of our agitator and his followers when, in the month of June, 1869, as a result of an order passed by the State Legislature, the Massachusetts Bureau of Labor Statistics was organized, the first of its kind in the United States. Henry K. Oliver was appointed Chief of the Bureau, with George E. McNeill as Deputy. Under the influence and inspiration of Steward, and under the more direct, although partial, supervision of his intelligent wife, the Bureau was conducted for the first four years in a manner that was satisfactory to all true friends of labor. For the first time in the annals of this country a voice favorable to labor was heard from an institution maintained by the State. In the annual bulletins issued by the Bureau the exploitation of women and children was severely condemned, the immoral and unsanitary conditions of New England factory life were statistically demonstrated, the brutality and rascality of both foremen and bosses were truthfully exposed, the shortening of the hours of labor and laws for the protection of the life and limb of the workingmen were stringently demanded.

But such aggressiveness on the part of labor agitators could be hardly tolerated by the upholders of capitalist “law and order.” The reports of the Bureau were replied to by capitalist editors and economists, who, with the true instinct of the class they represented, combatted the principle of State interference in the relations of capital and labor. “Hands off!” all of these cried in chorus. They charged the Bureau with painting the conditions of labor in too dark colors. From the standpoint of these gentlemen there was nothing to reform, since–so they claimed–the large volume of money deposited in the saving banks was sufficient evidence of the prosperity of the laborers, the needlessness of higher wages and the recklessness of the demands of the Labor Bureau. But the persons in charge of the Bureau were wide awake. In their annual report of 1872 the question of deposited money in the banks was carefully taken up. Basing their Basing their arguments on the reports of the Bank Commissioners and information volunteered by the large number of banks in the State, they proved indisputably that most of the money in the savings institutions were the profits on capital and not the savings from wages. This was too much for the capitalists. A storm of protests was raised against Steward and his friends–and their places were turned over to more “trustworthy” persons.

Ira Steward’s ideas of the labor movement were clear and definite, considering the conditions under which he was living. This was best seen at the time when the wave of “money reform” swept across the country–the movement of the Greenbackers. Unlike the great majority of labor leaders who were swept along by the false current, many of them mistaking it for a beginning of true revolutionary activity, Ira Steward raised his voice in condemnation of this issue, showing intelligently how all money questions are matters concerning property owners only. At that particular time it required much courage and unusual strength of character to take a rational stand on all labor questions. But nothing swerved Ira Steward from what he thought was his duty toward his fellow workers.

Never to the end of his life did our agitator slacken in his advocacy of the eight-hour working day. To him the achievement of this demand meant a stepping stone to labor’s emancipation, an essential road to the co-operative social order. So deeply did he feel on this question, so enthusiastically did he plead for it with whomsoever he came in contact, that he succeeded in converting statesmen, the most prominent being Charles Sumner of Massachusetts. This renowned senator voted in 1868 against limiting the working day to eight hours, but four years later, through the direct influence of Ira Steward, he stated on the floor of the United States Senate that he was anxious to vote in favor of the law which he opposed in 1868.

It might be mentioned here that by this time Steward had enlisted in the eight-hour cause a large number of persons. In 1869 the Boston Eight-Hour League was organized, a body that was for a long time the intellectual center of the labor movement in New England. Of course Ira Steward was the soul of the organization.

The great passion of Steward was to write a book on the subject, to which he was bending all his energy–the shorter working day. For years he had been collecting facts and all kinds of statistical data for the work that he was contemplating in the early sixties, under the title “Philosophy of the Eight-Hour Day.” It was to be his life work. Unfortunately, his hope in this respect was not realized. After 1876 he came in touch with New York Internationalists, Dr. Douai being one of them. His new relations pleased him much, as is evident from the letters which he wrote to friends in New York. The death of his beloved wife in 1878 completely unnerved him. Fearing that his “Philosophy of the Eight-Hour Day” would never see the light, he hastened to the West, where he hoped to be able to devote all his time to his literary undertaking. But his health was already shattered, and on March 13, 1883, his life came to an end.

The Comrade began in 1901 with the launch of the Socialist Party, and was published monthly until 1905 in New York City and edited by John Spargo, Otto Wegener, and Algernon Lee amongst others. Along with Socialist politics, it featured radical art and literature. The Comrade was known for publishing Utopian Socialist literature and included a serialization of ‘News from Nowhere’ by William Morris along work from with Heinrich Heine, Thomas Nast, Ella Wheeler Wilcox, Edward Markham, Jack London, Maxim Gorky, Clarence Darrow, Upton Sinclair, Eugene Debs, and Mother Jones. It would be absorbed into the International Socialist Review in 1905.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/comrade/v01n03-dec-1901-The-Comrade.pdf