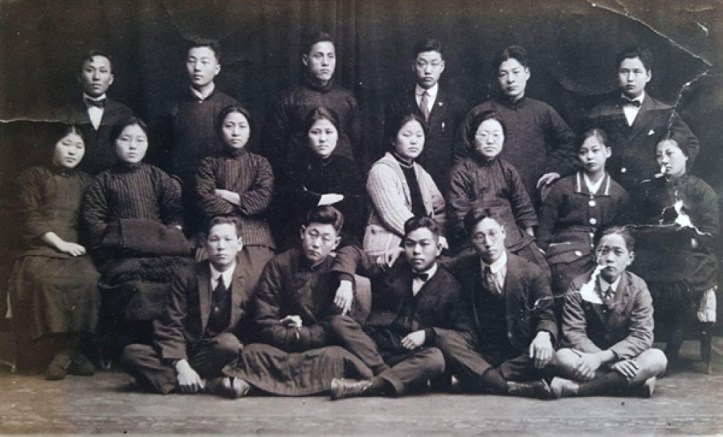

Moscow International University, 1929. 2nd from the left, Kim Tae-yeon (Kim Dan-ya), Park Heon-yeong, and Yang Myeong, from right back row, Park Heon-yeong’s first wife Joo Se-juk.

1926’s June Tenth Movement saw a new growth of Korea’s fight against the rule of Imperial Japan, now with Communist participation.

‘The National Emancipatory Movement in Korea Against Japan’ from The Daily Worker. Vol. 6 No. 181. October 5, 1929.

In the first period following the Japanese annexation of Korea, which was one of unrestrained Japanese military terror, when the. Korean bourgeoisie was prostrate and the industrial proletariat was practically nonexistent, the emancipatory movement in Korea was extremely weak, not having any firm foundation. Those partisan peasants organizations, such as the “Army of Justice,” which sprang up during the Russo-Japanese war, could not, of course, seriously cope with the regular, well-trained Japanese army. In spite of their exceptionally heroic struggle, the Japanese suppressed their movement towards 1914, and since then all mass revolutionary emancipatory movements temporarily die down, tightly held down by the iron fist of the Japanese imperialism.

However, this by no means signifies the disappearance of the people’s dissatisfaction with the Japanese policy in Korea. Reasons for this dissatisfaction at that time continually grew. The Japanese economic policy in the country, wholly directed to the rapid enrichment of the Japanese capitalists, to the fastest possible transference of raw materials and natural resources of the peninsular, mercilessly oppressed nearly all classes and sections of the Korean population. The following situation resulted from this policy towards 1919: In the country a rapidly growing differentiation brought about on the one hand by speculation in land and by the Japanese capitalists and limited stock companies and buying up large quantities of land, and on the other, by the support which the Japanese gave to the feudal landowning elements of the Korean countryside, and by the heavy taxes, which as a result of the occupation fell upon the peasantry. The number of land-owners doubled between 1914 and 1919 (from 46,000 to 90,000); at the same time the poorest population of the countryside also greatly increased (from 1,900,000 to 2,050,000 persons). The number of lease-holders and semi-leaders, i.e., of peasants leading a semi-starving existence, towards 1919 reached nearly 80 per cent of the total Korean agricultural population. There is no need to mention that the burdens (taxes and etc.) borne by the peasants were greatly increased. The condition of the city Koreans was not better. Retarding the development of the Korean bourgeoisie both by economic (competition, financial policy) and administrative means (the so-called “limited stock company law,” and etc.), the vast majority of the capital and production of the Korean industry was concentrated in their hands, while the Koreans owned only an insignificant fraction. This equally applied both to the mining and manufacturing industry. Owing to this the overwhelming majority of surplus values produced in Korea belonged te the Japanese; only leavings were allowed to the Korean bourgeoisie. Such a state of affairs became plainly unbearable for the latter, and was the cause of their great indignation, etc., regards the petty-bourgeois (city tradesmen and petty-trades), they, having fallen into the clutches of Japanese big capital, were forced to eke out a sorry existence.

The proletariat of Korea was at this time still very weak and scattered. It is absolutely plain its burdens were the heaviest. The proletariat of those countries where capitalism is only just going through the first stages of its development, always are especially severely exploited. In addition to all this, the Korean proletariat happens to be a proletariat of a colonial country, which means extra burdens, such as: extra low wages, cruel treatment, etc. Conditions are especially aggravated by the fact that in the same factory on the same job, Japanese work side by side with Koreans, and for the same work receive pay double that of the Koreans. This inequality between the pay of the Japanese and Korean workers is practiced all over Korea even now.

Thus, with the exception of only a small part of the feudal landowners, all the social classes had, towards 1919, sufficient causes to be dissatisfied with the Japanese. This dissatisfaction made itself felt in the uprising of March, 1919. Undoubtedly, the influence of such international facts as the October Revolution, the Treaty of Versailles and Wilson’s theses on the rights of small nations, etc., undoubtedly hastened the march of events.

The Korean proletariat was at that time too weak to lead the movement. It did not then possess any revolutionary organization, however weak this is proved that it had not yet become aware of its class interests.

The petit-bourgeoisie took charge of the movement; it had hitherto led the Chen-Do-Ghe organization (the Heavenly Way)–a religious nationalist organization composed mainly of peasants. However, the bourgeoisie proved itself absolutely unable to cope with its tasks in these March days. The whole history of its “leadership” is a history of cowardice and treachery, the movement developed on a large scale, only in spite of its leaders, who hastened either to fly or to voluntarily put themselves at the mercy of the Japanese, and owing to the spontaneous burst of indignation of the peasant masses, who led a fierce struggle against the Japanese.

The Japanese succeeded in drowning the first outburst of the Korean people in blood. All the same they were forced to consider the correctness (from their point of view) of their policy in Korea, and to consider how to attract to their side new strata of the population, which could be eventually used as Japanese agents in the emancipatory movement. It is but natural that their choice fell on the bourgeois, to whom it was decided to make certain concessions. In 1921, the following “reforms” were declared: the military governor-general was replaced by a civil governor-general, the gendarmes were replaced by police, a show of self-government was created, the “limited joint stock law” was repealed, and etc. Actually, however, up to the present day the governor-generalship is military, and self-government is not even heard of. (The so-called council attached to the governor-general and the provincial governors enjoy no powers whatsoever and are only obedient tools in the hands of the Japanese authorities) The economic yoke has been only very slightly relieved, and all the commanding positions of Korean economy remain as before in Japanese possession. However, in spite of all the ridiculousness of the reforms, the Korean bourgeoisie, frightened by the March movement no less than the Japanese, immediately grasped this straw in order to attempt to make even a patched compromise with Japan. Part of the bourgeoisie (the richer section) openly went over to the platform of collaboration with Japanese imperialism. The remainder, who would have wished to opposed Japanese imperialism, but feared, however, to lose that which it possessed, avoided a decisive struggle.

Hence, the half way position of this section of the bourgeoisie; frequent ultra revolutionary phrases side by side with dreams of reforms, the struggle for autonomy, culture, etc.

It would appear that all was over, but in reality the movement was not altogether crushed: at the least cause the popular masses once more evinced their willingness to fight their oppressors. The rice incidents of 1926 too was such an explosion of the popular indignation. The Communist Party, who had by that time come into existence, very ably took advantage of the mood of the masses, which that day filled the streets in large number (in Seul alone over 400,000) to mourn the death of the late emperor (allowing the masses to demonstrate, the Japanese had hoped that by arranging the solemn funeral of the emperor, they would lessen somewhat the anti-Japanese feeling). As a result of the Communist Party’s activities, and under their direction, this “public mourning” was converted into a powerful demonstration for independence of Korea.

There are in Korea at the present time only two really revolutionary sections which are ready to struggle to the end for emancipation: the peasantry and the proletariat. The peasantry, robbed and suppressed, are at any minute prepared to rush into the fight for land, for emancipation from the yoke of the Japanese and the landowners. They are not, however, in a position to organize and win this struggle on their own. They lack organizing forces, which can only come from the cities. The proletariat is that force which is capable of organizing the peasants for the struggle for national emancipation, for the land, for democratic freedom, and at the same time to organize, together with the peasantry, the other social strata which have retained traces of revolutionary spirit. The recent events (the Hensan strike) have shown that the Korean proletariat is quickly growing, that the period of disconnected action and unorganization of the Korean worker has gone by, that the time is at hand when the Korean proletariat will come out as a class, which has fully understood its historic tasks and which is capable of leading the Korean revolutionary movement to victory.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1929/1929-ny/v06-n181-NY-oct-05-1929-DW-LOC.pdf