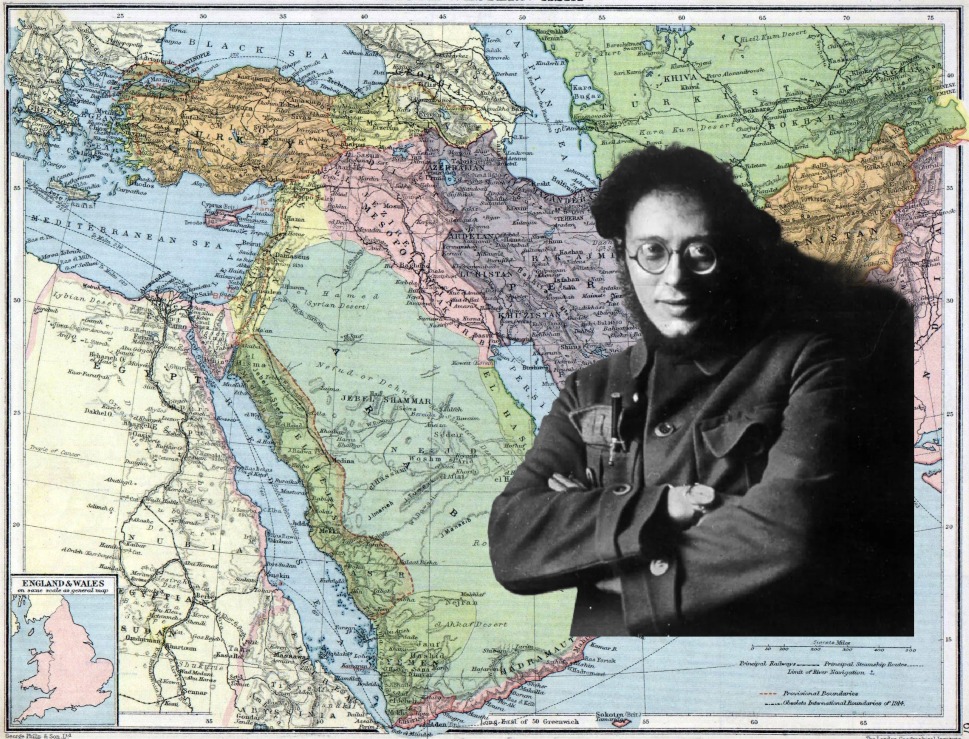

From Khartoum to Mosul, Karl Radek reviews British imperialism’s attempts to consolidate and expand its post-World War One control of the Arab world.

‘New Imperialist Attack in the East’ by Karl Radek from Communist International. Vol. 3 No. 8. January 15, 1925.

IN no place has the true meaning of the so-called democratic-pacifist era been so clearly revealed as in the Near East. And the most remarkable thing is that history had not long to wait for the revelation. Even before the fall of the MacDonald government it became clear that as far as the East was concerned, the so-called era of democratic pacifism (how ludicrous these words now sound!) simply meant that British and American capitalism had come to an agreement as to the measures to be taken with the aid of which the New York and London banks could create in the Far East the conditions for its enslavement to capitalism, and in the Near East for strengthening the imperialist policy of England. The support given by British and American capitalism to Wu-Pei-Fu in his struggle against Chan-Tso-Lin, which was supply an attempt to drive enfeebled Japan out of the positions she had gained in Northern China, the action taken by British and American capitalism against the government of Sun-Yat-Sen, the simultaneous efforts of the British in Persia to raise the feudal aristocracy of Arabistan against the central government which was endeavouring to create a national bureaucracy and army in Persia, those necessary foundations of a bourgeois state, the shameful policy of the government of MacDonald in Mesopotamia which tried terrorism to compel the Mesopotamian parliament to recognise the British protectorate, the policy of intrigue in Arabia, and, finally, the declarations made by Lord Parmoor and MacDonald in the British Parliament amounting in effect to a definite announcement that the Sudan would remain Egyptian, and Egypt would remain in the hands of England—all these facts make it now hopeless to pretend that the fall of MacDonald was necessary in order to clear the way for a fresh effort on the part of British imperialism in the East; of that there can be no question. The Conservative government is in a position to say calmly in reply to its Labour Party critics: “We are fighting for the same thing as you fought for, and if in the struggle we are obliged to use rather more severe measures than you employed, that is simply owing to the fact that the situation has become more acute, and not because of a change of policy.

The attack of British imperialism began in Egypt. In the weekly Observer, the English Conservative writer, Garvin, describes the murder of the British Commander-in-Chief, Lee Stack, as a bolt from the blue. That the murder was a bolt which will reverberate throughout the whole East, of that there cannot be the least doubt, but to assert that it was a bolt from the blue, is to assume one’s readers have a very short memory. Since the conclusion of the war, the Egyptian question has been an abscess on the body of the British Empire. The question is not only that the abolition of Turkey’s formal sovereignty of Egypt, as a result of the former’s entry into the war, made it essential that the attitude of England to Egypt should be defined. When the British protectorate was declared, Egypt was not the Egypt of the time when England, exploiting the debts of the Khedive, endeavoured to seize the country of the Nile. The resistance which was then offered came from a very small section of the Egyptian people in the shape of her feeble army led by Arabi Pasha. Forty years have elapsed since then, during which period capitalism in Egypt has been developing. Capitalism endeavoured to prevent the development of industry in Egypt, so that she might remain the supplier of cotton to England. But the mere introduction of commodity economy, the mere growth of exploitation and the impoverishment of the masses and the mere development of a native bureaucracy led to the creation of a large staff of intellectuals, who are giving form to the nationalist feelings of the people, and of a sufficient, if politically still rather undefined, Egyptian national consciousness. That during the period of the war, the national movement, which received such a powerful stimulus from the Turkish revolution, should not diminish was guaranteed by the exploitation of hundreds of thousands of Egyptian peasants in the Labour Corps created by the British military command during the operations in the Sinai Peninsula. The toying with ideas of self-determination by the Entente increased the boldness of the resistance offered by the national movement, with the result that the promulgation of the Protectorate met with a furious outcry on the part of Egyptian public opinion.

The incidents which have occurred in Egypt during the period from 1919 to 1922 and since the outbreak of the general strikes of railwaymen and telegraph servants on the banks of the Nile—the students’ demonstrations, the press and public agitation, the creation of secret societies and the formation of a parliamentary opposition—present a picture which is far from dear to the hearts of the imperialists. England was obliged to retreat before the attack of the Egyptian nationalist movement. The constitution of 1922 is the evidence of that retreat. But the retreat was only a formal retreat–England recognised Egyptian independence, but deferred to some future date the settlement of the questions of the Suez and the Sudan, of the situation of foreigners and of Egypt’s relations to foreign powers. As a precautionary measure for the future settlement of these questions, she left her army in Egypt. A nation consisting of 13,000,000 people was not in a position to impose its will by force upon British imperialism and British imperialism will never surrender its position in Egypt until it literally forces Egypt to her knees. England seized Egypt because of the Suez Canal, the important artery which serves the fragile organism of the British Empire. And England will never allow the Suez to pass from her hands until she is beaten. The loss of the Suez would mean the emancipation of India. Of course, England might be ready to agree on “internationalisation” of the Suez Canal which would cover her mastery of the canal under an international flag. But British imperialism will never consent to the real surrender of the Suez Canal into Egyptian hands.

But Egypt means something more than the Suez Canal. She also means—cotton.

A glance at the figures for the world production of cotton during the period 1911 to 1923 makes this clear.

What do these figures show? They reveal first of all a reduction in the world output of cotton. Cotton is one of the most important essentials for the economic power of Britain. Britain still possesses more spindles than America, France and Germany together. The United States has 37,250,000 spindles, France 9,600,000, Germany 9,500,000, while Great Britain has 56,500,000 million spindles, i.e., one-third of all the spindles in the world. Only 11-12 million spindles are required to serve Britain’s internal requirements and 44,000,000 are employed on supplying the world market; whereas, the United States exports only 5 per cent. of the output of its 37,000,000 spindles. Since England lives by foreign trade, and the textile industry is one of her chief branches of industry, the very fact of the reduction in the output of cotton is in itself a menace to England’s welfare of first class magnitude. But simultaneous with reduction in the supply of cotton, the demand in America for American cotton is growing. In 1923 the export of cotton from the United States diminished by two-fifths in comparison with 1913. At the same time cotton prices are rising; while a pound of cotton cost 13 cents in 1913, in July, 1923, it cost 33 cents. The question of increasing her own supplies of cotton has become one of prime importance for England. As the result of special efforts the output of Indian cotton has been increased, and she is now doing everything possible to increase the production of cotton in Egypt. Cotton production in Egypt is undergoing a crisis owing to a series of economic and technical factors; the absence of natural fertilisation renders the employment of artificial fertilisers necessary, as well as the improvement of its technique of cultivation in general. The cotton crop from the Cantar fell during the period of 1895-1913 by 42 percent.

The British Government found it necessary to enquire into the causes of the falling output, and a special commission which was appointed for the purpose came to the conclusion that the causes were to be sought in the impoverishment of the soil owing to the system of bi-annual change oi crops, inadequate irrigation, insufficient manuring and the degeneration of seed owing to the insufficient exercise of care in its selection, and the prolonged action of disease. To translate these technical questions into social language, the increase of the production of cotton demands that the exploitation of the fellaheen should not be carried to its present length, and that the general level of fellaheen education should be raised. Colonial capitalism, which is a system of merciless exploitation, is unable to make this transition to a higher and more intensive form of exploitation, and is obliged to seek salvation by increasing the area of exploitation. British imperialism has, therefore, resolved to extend cotton cultivation into the south of Egypt, to transfer British capital to the sources of the Nile. In order to increase the output of cotton in the Sudan it is, first of all, necessary to proceed with the irrigation of that region. The area which extends from the Sinai Peninsula to the White Nile, the so-called Valley of Ghezir, is capable of the production of many million pounds of cotton; for this all that is required is to construct a dam to hold back the Nile waters, and this step has been decided on by the Sudan syndicate which has taken the development of cotton cultivation in the Sudan into its hands. In the Ghezir Valley, there are about 800 acres of land suitable for cotton cultivation. The British Government is constructing a railway uniting the valley with the port of Sudan. The only hindrance was the resistance offered to the construction of a dam in the upper regions of the Nile, for that would constitute a menace to the already inadequate irrigation of Egypt.

Fearing the mood of the Egyptian population, the British Government has hitherto agreed to set a limit to the amount of land in the Ghezir Valley which should be subject to irrigation. The murder of the Egyptian Commander-in-Chief has now furnished the Conservative government with a pretext for overcoming the resistance to the transformation of the Sudan into a cotton colony. The colony is now entirely in the hands of the British. The Sudan, as we know, was conquered by Egyptian troops, led by Kitchener. The crushing of the revolt of the Madhis, the expenses of which were paid by the wretched Egyptian fellaheen, who himself, fed on bread, water and cotton-seed oil, was followed by the treaty between the governments of Egypt and England which set up the condominium over the Sudan. The Sudan was administered by an Egyptian bureaucracy. Only the very highest posts were in the hands of the British. The army which occupied the Sudan was an Egyptian army.

The first imposition made on the government of Egypt by British imperialism after the murder of Lee Stack, was the withdrawal of the Egyptian army and the complete transfer of the administration from Egyptian hands to British. The second point of the ultimatum was a declaration to the effect that England refuses to bind herself by any limitations regarding the extent of land in the Ghezir Valley liable to irrigation. In this manner, British imperialism created a new point for “further negotiations” with Egypt—the establishment of the condominium in Sudan; the direct subordination of the Sudan to England. British imperialism now menaces Egypt not only from the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean, but also from the South, holding over her the threat of the retention of the waters of the Nile, which would be equal to the passing of a sentence of death on everything living in Egypt. Railway and telegraph strikes on the line to Khartoum to Cairo and demonstrations of students are of little avail against the guns and the tanks which the British satrap daily displays in the streets of the Egyptian towns. It is easily understood that in a country which has already been awakened, the masses of which are already in movement, imperialism cannot govern in such an open and brutal form without leading an open collision between the colonial revolution and the imperialist counter-revolution. In the article of Garvin we have already referred to, he warns the humane public, which has been terrified by these uprisings and demonstrations in Egypt, that during the three days which followed the murder of Lee Stack, England was in a position of grave danger, and it was only the demonstration of firmness and force which saved the situation. But one cannot “demonstrate firmness and force,” every day without weakening their effect.

Egypt is far too feeble to be able alone and isolated to overcome British imperialism. But the soil of Egypt is volcanic, and the ground trembles under the feet of British imperialism. And England knows that with the first great complication which occurs to tie up her forces, she will be confronted with mass uprising in Egypt, and a revolutionary movement which will constitute a menace if not to the heart of British imperialism, at least to the finest of its connecting nerves.

Simultaneously with the events in Egypt, England suffered a series of defeats in other countries of the East. British policy in Arabia was an attempt to unite the Arab tribes with the aid of the Hashemite dynasty. Hussein in Mecca, Feisul in Bagdad, and Abdul in Trans-Jordania were to prevent the union of the Arab tribes, on the one hand, and on the other, to maintain the whole of Arabia in the hands of the British. Meanwhile, England was undermining French imperialism, which holds Syria. But this policy has failed. The Hashemite dynasty has proved itself too feeble for the part British imperialism expected it to play. In Mesopotamia, King Feisul is subject to the growing pressure of the local Arab population, which is hostile to British imperialism. He holds his power solely with the aid of British bayonets and is, therefore, in no position to assist England. Hussein has already been swept away by the pressure of the central Arabian tribes, the Wahabites. British imperialism is endeavouring to enroll these tribes into its service under the leadership of King Ibi-Soudom, but this will be a very short-lived combination. The Arab movement, to which even before the war, so careful an observer as the well-known German Arabist, Professor Martin Hartman, attributed considerable importance, is now a far greater force than is usually believed in European circles. The Wahabite tribes are the most primitive, but militarily the strongest, and nationally and religiously the most active section of Arabia. Attempts to secure their support are not likely to lead to favourable results, and England, therefore, as we shall see later, is following the development of events with profound alarm.

The attempts to sever Arabistan and the oil of Southern Persia from the whole of Persia, and thereby to secure the simultaneous control of the oil both of Mosul and of Persia, has ended unsuccessfully. The national bourgeois movement of Persia, which has its parliamentary expression in the Medjlis and its military expression in the Persian army created by the soldiers of Riza Khan, have proved to be stronger than the agents of British imperialism in Persia, who, owing to the efforts of venal diplomatists, fail to observe the growing national strength of Persia, cared to admit.

This series of defeats confronted British imperialism with the general necessity of securing fresh guarantees for the consolidation of its mastery over the Near East. Wherein does the menace of that mastery consist? There are three factors: (1) the national movement among the Mussulman peoples; (2) the influence of the Russian Revolution upon these peoples; and (3) the competition of the imperialist powers among themselves. British policy with regard to the Mohammedan peoples has undergone a series of changes since the war. In 1919-20, England was conducting a wholesale attack upon the national movement in the Near East; she was conducting war on Turkey with the aid of Greek hirelings; she was endeavouring to suppress the national movement in Egypt by repressive measures and seeking support for herself in the Arab movement. She was endeavouring to bind Persia by a treaty which would make the British masters of the situation.

Simultaneously, she was attempting by means of intervention to crush the Russian revolution which was the hearth of colonial revolution. And, finally, she was conducting a systematic war against France, who had seized Syria in order to extend her influence in the East. In 1922 we see the attempt made to come to an agreement with the Mussulman movement, and to isolate it from Soviet Russia. England recognised the independence of Egypt after suffering defeat in Asia Minor; she endeavoured to reach agreement with Turkey and come to terms with Persia which had torn up the treaty of 1919. At the same time, Curzon presented his ultimatum to Soviet Russia. This policy has now been proved bankrupt. England has only aggravated her relations with Soviet Russia and. with Egypt; in Egypt she is conducting a regime of savage terrorism; in Arabia and Southern Persia she is suffering defeat. In Turkey clone, which is enfeebled by a long financial boycott, where the urgent economic demands of the peasantry can no longer be deferred and where a profound social disintegration is taking place, is British imperialism making slow progress and stands some chance of securing control of the oil of Mosul with the aid of financial bribes. In this truly difficult situation, British imperialism is endeavouring to secure the neutralisation of at least one source of its enfeeblement, namely, the competition on the part of other imperialist powers, and of France in particular. France herself is very much alarmed by the growth of the national movement in her Mohammedan colonies. One has only to read the book which has just appeared in Paris entitled “A Guide to Mosul Policy,” by an author writing under the pseudonym of “African” to realise what importance France attributes to the growing national consciousness of the Mohammedan peoples. Describing the growth of the movement in Turkey, Persia, Afghanistan, Egypt, Morocco and Tunis, the author points out that in 1900 only 200 Mohammedan papers were being published throughout the world; in 1914 there were 1,000, and that number has now been doubled. Ten years ago, the author says, an intelligent Moroccan had not the slightest interest in the Mussulman movement, he merely maintained religious contact with Mecca. Nowadays, however, a Moroccan youth will not only read the growing press of Morocco; he will also read the newspapers of Tunis and Egypt, and displays the liveliest interest in all that is going on in the Mahommedan world. Herriot very soon after he came into office appointed a commission to go into the question of the extension of self-government in Tunis. When imperialists begin to talk of self-government it means that there are already forces at work fighting for freedom, and that the danger of the Mussulman movement is increasing the world over, menacing French imperialism also. The importance of the Mediterranean Sea was clearly demonstrated by the Spanish defeats in Western Morocco. British diplomacy is taking advantage of the moment by attempting to arrange a deal between England and France for mutual support against the Mussulman movement. It is prepared to recognise France as the heir of Spain in Morocco, demanding of French imperialism in its turn that it should not extend its control to Tangiers which lies opposite to Gibraltar. Tangiers is to remain internationalised, but actually to be under the control of England. Both sides are to refrain from mutual conflicts. The French Government must not take advantage of British difficulties in Egypt. In Syria and Arabia, the British and French pro-consuls are to assist each other in the common struggle against the Mahommedan movement. Anglo-French competition in Turkey may be abandoned. The first news of the attempt to create an Anglo-French Entente in the Near East not only caused alarm in every centre of the Mussulman movement, but also brought forward another candidate for alliance in the shape of Italy. But Italy is demanding some reward for her participation in the alliance, that is, she is maneuvering to take advantage of the danger threatening British and French imperialism in order to strengthen her own positions.

In the Far East, the Anglo-American co-operation directed towards making Wu-Pei-Fu the head of a united China, the geographical position of which, lying as she does between the Hong-Kong and Yangtze-Kiang Rivers, makes her the object of constant pressure on the part of Anglo-American capitalism, has so far ended in utter failure. The Japanophile party, the An-Fuists, have returned to power. The An-Fuists represent the followers on a national scale of Chan-Tao-Lin, whose position in Manchuria makes him willy-nilly the presentative of Japanese interests in China. The United States and England have not revealed themselves to defeat. Attempts to consolidate the forces of Wu-Pei-Fu in the territory he occupies, are being made, in other words, preparing for civil war in China. England, and in this cast, America, are doing everything possible to bring in France, who has been maneuvering on the side of Japan against them. At the same time material and moral pressure is being brought to bear upon Japan. The 150 millions which Japan has borrowed this year are not enough to cover her demand for fresh capital caused not only by the earthquake, but also by her trade balance, and he general economic situation of the country. During the first half of 1924, Japan imported goods to the extent of 14 million yen more than she exported. Japan needs private credits in order to finance her imports. She is being forced to sell and pledge her industrial shares in America. America is making preparations for grand maneuvers which are to take place in the beginning of 1925. The whole American fleet in the Pacific and Indian Oceans are to act in conjunction. It is to sail from San Francisco in February for the Hawaiian Islands in order to demonstrate to Japan the fighting power of American capital.

In 1925, world imperialism will attack on all fronts in the Near and Far East. But these imperialist attacks will only partly be the result of the consolidation of imperialism. One can speak of the increasing strength of imperialism only with respect to the United States. As far as England and France are concerned, the intensification of imperialist pressure is more the expression of enfeeblement, fear, and alarm for the future. Their attacks are more counterattacks against the national movement which is growing throughout the whole East.

1925 will be a year of testing of strength, a year of great imperialist conflicts and revolutionary movements in the East.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/new_series/v02-n09-1925-new-series-CI-riaz-orig.pdf