Under capitalism, ‘labor-saving’ devices generally mean lost jobs rather than less work. A look at the mechanization of the grain harvest, which once employed hundreds of thousands of hands.

‘The New Harvester’ by Winden E. Frankweiler from The International Socialist Review. Vol. 13 No. 11. May 1913.

Another Job Killer

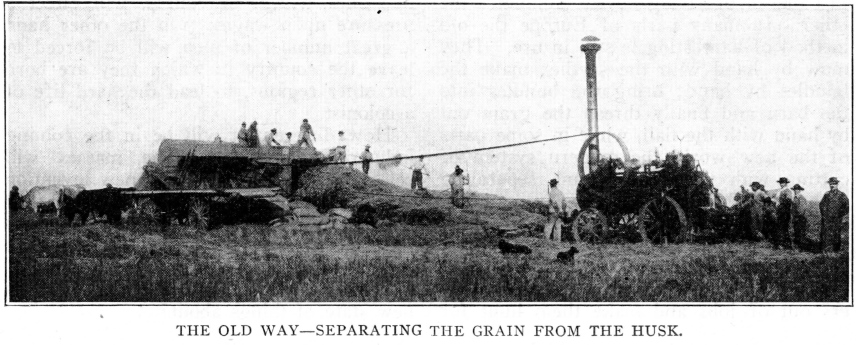

ONE of the hardest jobs of the farm hands is the work on the threshing machine, which separate the grain from the straw. In the northern part of the United States and in Canada the threshing time falls in the early part of winter, while in the southern hemisphere, for instance, in Argentina, threshing begins in December, which is midsummer there.

The work itself is not so very fatiguing, the excessive long hours and bad conditions during the work and rest, strain and discourage the men.

Early in the morning, long before sunrise, the steam whistle announces the time to get up, while late in the evening, by moonshine or artificial light, the threshing machine is still busy. This is so because the threshing machine boss is paid by the weight of the separated grain, and “naturally” tries to get out of the men as much as possible. So it means 16 to 18 hours of practically continuous work either in bitter cold and deep snow or terrible heat, not to forget the dirt and dust produced by the separator, which the workers must inhale. On the top of that frequently come poor food and small pay, especially so in Argentina.

And where do you think the men sleep? A farmhand once asked the owner of a big ranch for a place to sleep and got the typical answer: “I own 25,000 acres of land so I hope you will be able to find a ‘place to sleep.'” Only imagine a cold night with rain or snow and practically no shelter. In the southern part of the globe, where nature is more generous in this regard, the mosquitos rob the workers of the half of the much needed rest.

A new machine is coming now which will liberate the workers from that drudgery, but, alas, this machine, called “The Harvester,” is not an exception to the rule.

These modern inventions do not make work easier; they take the job altogether.

To give a clear idea what this new machine means to farmhands and mechanics, I must explain the modern method of harvesting cereal.

A machine called the binder and which is pulled by horses, cuts the stalks of the wheat, etc., binds them into bundles, which it disposes alongside while moving over the field. These bundles are put together in small heaps of 4 or 5 and later on gathered to be piled up into large stacks.

There is also another system in use where the machine cuts only the ears of the cereal plants and deposits them into a wagon which, when loaded, will go at once to the stack.

To perform this work at least 5 to 6 men and 6 to 8 horses are necessary.

The grain remains on the stacks at least 2 weeks to “sweat” or until the thresher comes along.

As the threshing machine outfit consists of the grain separator proper, a steam or oil engine to drive it and also a water-wagon and a kitchen-wagon, it is much too expensive for the average farmer to buy. So the whole combination together with the gang has to move from farm to farm. The engine and the separator are placed alongside the stack and several men deposit the bundles or the ears upon a rolling gangway which conveys them into the separator. The grain falls then into bags on one side while the straw is thrown out on the other side of the separator.

To keep the threshing machine going, several horses and up to 15 or 20 men are needed.

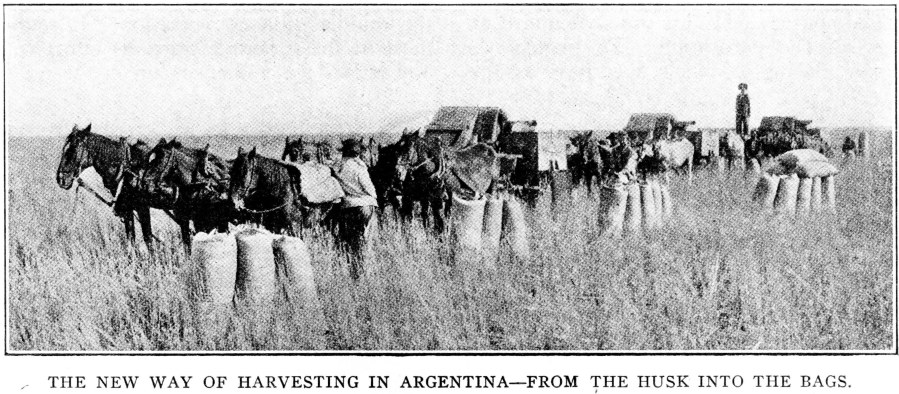

Now let us see what the “Harvester” machine can do. It harvests in the real sense of the word; it cuts off the ears, separates and bags the grain in one single operation and, if necessary, one man alone can handle and attend the machine.

So a farmer owning 150 to 250 acres can easily bring in his wheat, oats or barley without any outside help. He drives the “Harvester,” his 14-year-old boy takes off the full bags and puts on empty ones, while his wife sews the bags.

As a harvester is not much more expensive than a binder, the average farmer will be able to buy one. What are the farmhands going to do then?

There seems to be one disadvantage with the harvester, which is, that the grain has no chance to “sweat” on the stacks, and therefore turns out a little pale. The farmers get a trifle less for it, but the “Harvester” saves such a lot of labor (and therefore money)—which is the principle today—that its success is assured.

For some reason the “Harvester” is not much in use yet in the United States, probably because the International Harvester Company does not yet control its patents. But in South America, and especially in the middle part of Argentina, the “Harvester” is rapidly coming into general use. Thousands of them are imported every year from Australia and Canada. On some big ranges as many as 100 of them are used. This shows that the machine in question undoubtedly has passed the experimental stage and has proved to be successful and satisfactory.

Not only the agricultural workers will be affected by the coming of this machine. As the manufacture of the “Harvester” takes about the same amount of work as the binder, so the machinists that build the many thousands of oil or steam engines and separators every year, will be out of a job.

Furthermore the great number of machinists and engineers who attend to the steam engines and separators during the threshing time will no more be needed.—What are they going to do?

We have here a typical example of how rapidly modern science works, and how fast one labor-saving device eliminates the other. In many parts of Europe the old method of harvesting is still in use. They mow by hand with the scythe; make the bundles by hand; bring the bundles into the barn and finally thresh the grain out by hand with the flail, while in some parts of the new world the modern system of cutting with the binder and separating with powerful engines is already outdated. Now, what good does a new machine like that do the workingman in our present system of society?

It will throw many thousands of laborers out of jobs and make them hunt for new ones, which, of course, will effect a pressure upon wages. On the other hand a great number of men will be forced to leave the country in which they are born for other regions, to lead the hard life of a colonist.

How different it will be in the coming industrial democracy. The masses will celebrate and welcome every new invention that does the hard work for them, for they will cut down the working hours and so save more time to be used according to each individual’s taste and inclination.

What are you going to do to bring this new state of things about?

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by AM Simons and later Charles H. Kerr and loyal to the Socialist Party of America and is one of the essential publications in US left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v13n11-may-1913-ISR-riaz-ocr.pdf