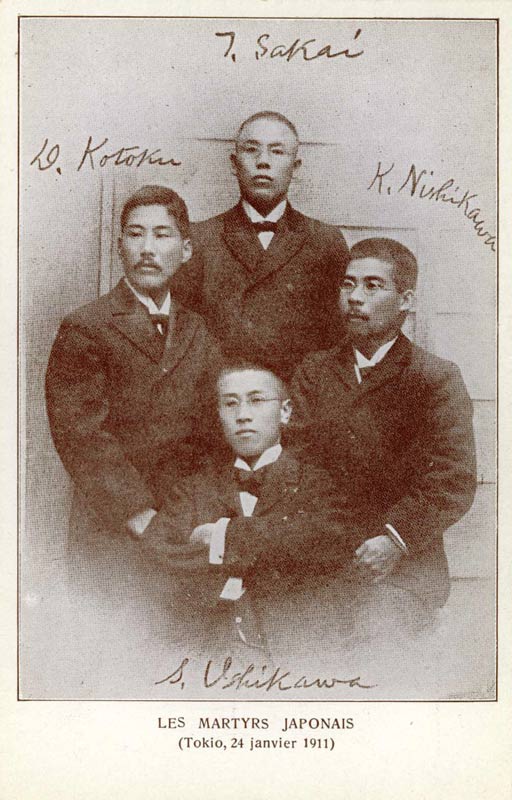

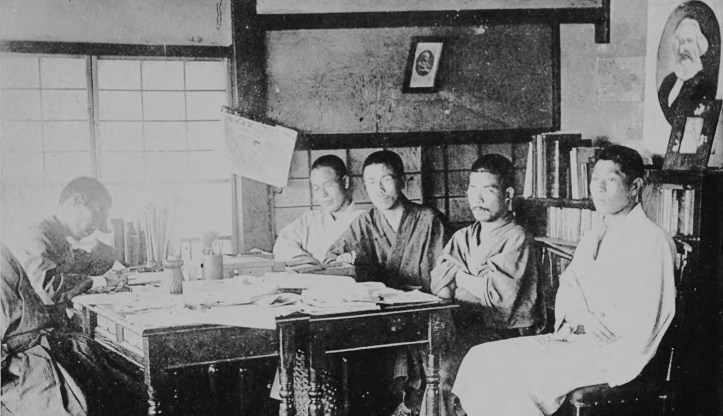

A central figure in modern Japanese radicalism, Denjirō Kōtoku was editor of Heimin Shinbun (News of the Common People) who would be executed for his revolutionary politics along with eleven comrades in 1911’s High Treason trial.

‘Japan’s Twelve Noblest Souls’ by Shidsuwe Tatsune from Progressive Woman. Vol. 4 No. 48. May, 1911.

On January 24th, 1911, sleet was heavily falling upon the silent metropolis of Japan; twelve times solitary echoes from the gallows of Sugamo Prison died away in gloomy silence of the winter sky. The twelve noblest souls of this island empire breathed their last farewells to dear old Japan and her people, serene and calm, with the vision of coming enlightened days; thus they engraved their names upon the eternal marble of the world–the history of martyrdom–with Socrates, Galileo, Georadano Bruno and Francesca Ferrer, over which reminiscent humanity will weep forever. Their only crime was their brave utterance of Truth; their passionate love of their forty millions of brothers suffering in hunger and tyranny; their sincere endeavor to emancipate the unfortunate islanders from the chain of ignorance and superstition of centuries; their devoted propaganda of the blessed gospel of human brotherhood and love.

The ruling class of Japan is now laughing aloud at the success of their massacre, exposing their blood-tainted teeth in broad day light in utter shamelessness, while unknown thousands of hearts are burning with indignation, and the whole land is full of sobs.

A copy of a faithful translation of the official statement which explained the legal reason for the death sentence read in court on January the 18th is eloquent testimony of the injustice of the murderer–the Mikado’s government.

The poor sophism the wicked officials used to condemn our twenty-four “humanitarians is founded upon several data of so-called criminal evidence, which, according to the above-mentioned bill, consists of “postal cards exchanged among them concerning their dreadful plot,” “the incident that one day Kotoku was in an interesting manner looking at the picture of a bomb in a western paper,” “the fact that Kotoku was an enthusiastic student of Peter Kropotkin in whose communistic doctrine dignity and right of state is denounced,” “Kotoku’s speech upon the subject of the Paris Commune at a Socialist gathering.” They labored in vain to connect the incident of some dynamite found in a lumber room in the Province of Nagano with Kotoku; there was not sufficient evidence to prove his connection with this,

Regarding the others–Dr. Oishi, Miss Suga Kanno, Morichika, et al., the same. sophistication, with judicial rhetoric in a vain and dignified air, without ground of evidence, was freely used.

The court insisted upon a confession by Kotoku and others, regarding their plan of murdering (?) the Mikado, which was heard by no one but the judges, a few privileged and officially appointed lawyers, two foreign diplomats, an Englishman and a German who were deaf to the Japanese language, and who simply endured their boredom, sitting on a chair all day in one of the secret trials.

A recent number of Jiji, one of the leading papers of Japan, reports the rumor that the judges and prosecutors who took part in the trial held a champagne sakamori (a drinking bout) to rest the strain upon their energy immediately after retiring from the court where our comrades were sentenced to death (Out of sympathy, let me sincerely hope that that shower of champagne intoxicated them to the marrow of their consciences, so that they lost their dreadful consciousness of criminality–at least for a few moments!)

Thus we have our “great men” on the one hand trying to drive away painful memories of their murdering of innocents with glasses of champagne, and on the other, hand we have them endeavoring to stupefy the whole nation of Japan with sophistry, inspiring insane patriotism and loyalty among the people through the newspapers of Tokyo. (All newspaper articles about this case are under strict censorship of the public prosecutor; even slight indication of sympathy to the martyrs will give them the “right” to prohibit publication–as the Manichi News, for example.)

And beware, whole Western world. The Government of Tokyo, not satisfied with cups of foaming champagne which they drank to paralyze their conscience; not satisfied with inspiring false patriotism to deafen public intelligence, now are going to send a statement of this case to all western countries through their ambassadors, to silence the indignant voice of Justice in the world with lies. (An authority of the Tokyo government told a newspaper reporter that they are quite annoyed by the shower of inquiries and reproaches from foreigners about their secret trial.)

Recent cable reports have it that Mr. Tokutomi–a prominent writer and student of Tolstoy–made a strong, enthusiastic appeal to the youths of Kotogakko, a government college, in commemoration of Kotoku: his emphatic, “Japan owes him nothing but thanks for his life’s deeds,” was interrupted by sobs and denunciation of the brutal ruling class.

This cost him prison and his resignation to President Nietobe. What motive drove Mr. Tokutomi, a peaceful Christian writer, out of his hut on the farm Kitatoyoshima, for the sake of a strong atheist like Kotoku? The voice of justice! Nothing more.

Kotoku was the one who translated the great Tolstoy’s essay on the Russo-Japanese war; boldly, amid the curse and attack of the crazed patriotic mass, as well as the indignation and persecution of the Mikado’s government,

He was the one who poured the revolutionary blood of LaSalle into the veins of Japanese youths through his pathetic biography of this giant Socialist.

He was the one who thrust Gustave Harve’s anti-militarism into the heart of this despotic monarch.

He was the one through whom Kropotkin could incessantly whisper to awaken the younger generation of Japan.

He was the one whose teaching made a youth prefer the gallows to slaughter of his Russian brethren.

He is the one who had given up a prominent editor’s chair in a leading newspaper of Japan–Yorozu-Choho–because of his hatred of the blood-shed of war.

His life through and through was that of a warrior’s, of a brave soldier of the humanitarian movement. With his face to the goal of his noble idea he marched on: loss of health could not stop him; utter poverty could not bar him; four imprisonments not only did not discourage him, made him still more courageous. Thus marched until he finally embraced the gallows with a sublime smile on his face where, with his twelve followers, he shouted “Ban Zai!”

The Socialist Woman was a monthly magazine edited by Josephine Conger-Kaneko from 1907 with this aim: “The Socialist Woman exists for the sole purpose of bringing women into touch with the Socialist idea. We intend to make this paper a forum for the discussion of problems that lie closest to women’s lives, from the Socialist standpoint”. In 1908, Conger-Kaneko and her husband Japanese socialist Kiichi Kaneko moved to Girard, Kansas home of Appeal to Reason, which would print Socialist Woman. In 1909 it was renamed The Progressive Woman, and The Coming Nation in 1913. Its contributors included Socialist Party activist Kate Richards O’Hare, Alice Stone Blackwell, Eugene V. Debs, Ella Wheeler Wilcox, and others. A treat of the journal was the For Kiddies in Socialist Homes column by Elizabeth Vincent.The Progressive Woman lasted until 1916.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/socialist-woman/110500-progressivewoman-v4w48.pdf