Six hundred years of Hapsburg rule came to its end with the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian empire at the end of the First World War–part of a wave of revolutions that accompanied the ‘peace.’ One of the states to emerge in the Empire’s aftermath was the Hungarian Soviet Republic, lasting just four months. Ludwig Lore on its character and how it came to be.

‘Communism in Hungary’ by Ludwig Lore from Class Struggle. Vol. 3 No. 2. May, 1919.

The second revolution in Hungary, which overthrew the coalition ministry under Karolyi and substituted for the futile efforts of a bourgeois-social-patriotic government a dictatorship of the proletariat, created a profound stir all over the world. While the European and the American capitalist press immediately interpreted it as a “nationalistic revolution,” it cannot be denied that the Peace Conference at Paris received the news of the overthrow of the Hungarian Republic with dismay. For this new proletarian government gave an entirely new direction and impetus to their negotiations, and their attitude toward Bolshevist Russia was to a large degree determined by this astounding turn of events.

The first Hungarian revolution created little attention. It was completely overshadowed by the events that were transpiring in Germany, where the overthrow of the Imperial government was making history, not only for Germany but for the entire civilized world. Like all revolutions in modern times, the reasons that culminated in this outbreak were various and diverse in character. The people of Hungary had suffered untold hardships during the war. The oppression and exploitation to which the Magyars of Hungary had been subjected at the hands of their Austrian rulers in times of peace were increased a hundredfold when war, with its rule by the power of arms, swept over Europe. Hunger and suffering stalked throughout the land. And for the people of Hungary there was no patriotism, no love of fatherland to alleviate the hardships they were forced to undergo, and to blind them to their sufferings. Hatred of Germany and of the German-Austrian rulers, who were responsible for the misery that engulfed them, was the sentiment that dominated the first revolution in Hungary.

It was only natural, therefore, that the new government, under Karolyi, should be distinctly pro-Ally in its sympathies. As in Germany and in Russia, the power of government was first placed into the hands of a coalition ministry, a combination of socialist and bourgeois elements–under the nominal domination of labor. Count Karolyi, the head of the new republic, was a liberal democrat of the finest type, honest in his intentions. But just as the Kerensky government in Russia was doomed to failure, and just as surely as the Scheidemann-Ebert regime in Berlin will finally succumb to the insistence of the proletarian demands of the German people, so the Hungarian republic, with its democratic ideals was doomed to destruction. From the beginning, the young republic was involved in a mire of difficulties. There were nationalistic prejudices, especially on the part of the propertied classes, which were a constant source of irritation. The returning soldiers made insistent demands, demands that were recognized in principle, but whose fulfilment was out of the question for a government that respected the property rights and interests of the wealthy classes. A system of agrarian reform that satisfied no-one was promised, but the government did not have the courage to approach its realization. Unemployment insurance measures were instituted, but succeeded only in arousing the dissatisfaction of the returning troops, because they were insufficient to satisfy the demands the latter felt justified in making. “Make the rich pay” was the note that dominated the demonstrations held all over the country. Strikes became more and more frequent. The working-people in the industrial centers were strongly socialistic, and demanded that the interests of the working-class alone henceforward control the forces of industry. They demanded wages that the capitalists could not afford to pay without serious curtailment of what they considered their legitimate profit. The result was a threatening standstill in the machinery of production, that increased the number of unemployed on the one hand and decreased the supply of products on the other. The urban population of Hungary has always been strongly organized, and belongs to the radical element in the labor movement. Thus, dissatisfaction in the country was rife as well. The brief history of the Hungarian republic was one of constant uprisings.

In this respect Hungary differs in no way from the other revolutionary countries of Europe. What happened in Hungary is happening in Germany at the present time, and is a repetition of the experiences that the Kerensky regime in Russia was forced to undergo. It is proof, if proof is still needed, of the impossibility of restoring order and normal industrial conditions in any country, under a system based upon the co-operation of the political representatives of both the capitalist and the working class. The least that a working-class government can give will discourage capitalist production sufficiently to create a definite and threatening problem of unemployment. There exists, under such a form of government, the constant danger of a counter-revolution, because its methods must inevitably leave in existence a dangerous, because extremely dissatisfied, capitalist class. On the other hand, the demands of the working-class, who, under what they consider a Socialist form of government, refuse to take into account interests and needs of capitalist production, leave only one possible solution—complete socialization of industry. Workingmen who will willingly submit to hardship and sacrifice, when this sacrifice is demanded by the interests of their class, will and must refuse to do so in order to help build up the industries of the nation for the profit of their owners.

Preparations for the election to the National Assembly were under way. While there was no strong organized opposition to this Assembly, such as was carried on in Germany by the Spartacus movement during December and January, the working-class as a whole looked upon these elections with open skepticism. Although the majority-Socialist had finally decided to officially participate in the election, it was only after a long and serious discussion, a strong element in the party being in favor of such an election only if the absolute majority of the Social Democracy in the Assembly could be guaranteed at the outset. In the meantime Communist agitation was arousing the country. There were uprisings everywhere. Insignificant incidents often led to open rioting. In Kiskunfelgyhaza, a small town near Szegedin, an altercation between a merchant and a would-be purchaser over the price of a piece of cloth led to the plundering of the merchant’s shop by the crowd that had collected, Police and guards who where sent to restore order were disarmed. The assembled masses set up a machine gun in front of the plundered establishment and began to fire. The merchant was killed. The riot persisted through the entire night and was only quelled the next day by the arrival of a detachment of sailors who placed the town under military law.

On the same day, February 19, a Communist demonstration in Budapest, in which about 4000 persons participated, went from place to place through the city, holding protest demonstrations and finally assembled before the home of the Hungarian Socialist organ, the Nepszava. Fifty policemen had been sent by the authorities to meet the oncoming demonstrators. The latter assembled before the newspaper building with hoots and cat-calls, until the police began to disperse the crowd. A shot from a neighboring- house called forth an answering volley from the crowd. Hand-grenades were thrown and several persons were more or less seriously wounded.

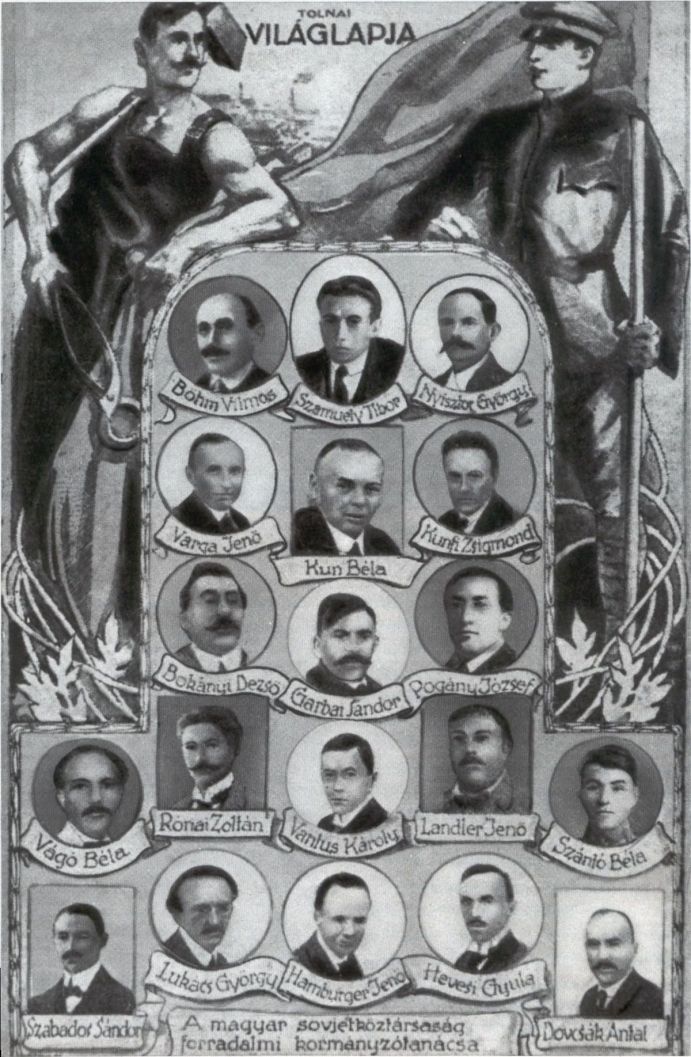

As a result of these and similar uprisings 56 Communist leaders, among them Bela Kun, Bela Vago and Dr. Eugene Lasslo, were arrested on March 5th by the coalition government.

The inter-political situation in Hungary had undoubtedly reached a critical period. Nor was the international situation, in so far as it affected the affairs of the Hungarian republic, more promising. Under the terms of the armistice between Austria-Hungary and the Allied nations, a large part of what had been Hungarian territory was occupied by Allied troops. This occupation was rendered particularly irksome to the national instincts of the Hungarian people, because these troops came from the smaller nations who had always constituted a menace to the Hungarian frontier. Its most fruitful stretches of land were given over to the Tchechians in the North, to Rumania on the West, to Servia on the South. There were frequent clashes between the population and the occupying forces, that kept alive a bitter spirit of resentment. About the middle of March, Admiral Trowbridge ordered the Hungarian government, without previous negotiations, to deliver all navigation rights upon the Danube into the hands of the Tchecho-Slav Republic. This cut off Hungary from one of its most important industrial resources, in spite of the fact that the Tchechian racial population extends nowhere nearly as far as the arbitrary borderline established by this order. A few days later the Entente officially capped the climax by sending the famous note that gave to Rumania an important portion of Hungary, making the military lines established by the armistice permanent. The coalition government was placed before an impossible alternative. To submit, meant open revolution in Hungary. To refuse, meant war with the Allies. And neither Karolyi nor his cabinet were prepared to undertake this step. There was but one way out of the situation. Count Karolyi resigned with his cabinet and turned over the political control of the nation to the Workmen’s and Soldiers’ Council, “to insure the rule of the proletariat and as a protest against the Imperialism of the Entente.” Karolyi resigned, as the words of his proclamation plainly show, because conditions at home, as well as the state of foreign affairs, had reached a crisis that he and his government could no longer hope to control.

Since the establishment of the control of the Workmen’s and Soldiers’ Council on March 22, events have moved with startling rapidity. The new government, a coalition of all wings of the Socialist movement, has undertaken the immediate socialization of Hungarian industrial resources, as the only means of stabilizing industrial conditions and preserving the country from complete collapse. According to a proclamation to the whole world:

“…the Social Democratic Party and the Communist Parties of Hungary have united into a single party and have created a dictatorship of the proletariat without the loss of a single drop of blood. For the present, the powers of government lie in the hands of a Council of People’s Commissaries, until such time as the National Congress of Workmen’s and Sailors’ Councils shall decide upon the ultimate form of a Soviet government. The Hungarian proletariat has unanimously united its forces under the flag of the dictatorship of the proletariat and of the world revolution. It will take up the struggle against the Imperialism of the capitalist governments, hand in hand with the Soviet government of Russia and with the proletariat of the entire world, who have recognized that in the open revolution of the united workers, soldiers and peasants lies the only possibility of crushing the forces of international Imperialism and of realizing our Socialist ideals.

“The Hungarian proletarian revolution arose out of two causes: the one was the determination of all poor peasants, proletarians and soldiers no longer to bear the oppressive yoke of Capitalism; the other cause was the Imperialism of the Entente, which threatened to deprive the people of Hungary of all supplies, of its raw materials, and of the very possibility of existence by dividing up its territory among the neighboring nations.

“The ultimatum of the Entente demanding the immediate cession of one-half of the nation to the Rumanian oligarchy was answered by the Hungarian people with the establishment of a dictatorship of the proletariat. The Tchecho-Slav and Rumanian conquerors hope to defeat the revolution of the Hungarian proletariat by force of arms. We appeal to the Tchecho-Slav and to the Rumanian soldiers to refuse to obey, to mutiny and to turn their weapons against their own oppressors, that they may not become the hangmen of their brothers, the workers and soldiers of Hungary. We call upon the Tchecho-Slovak peasants and workers to shake off the yoke of their oppressors.

“Although we are determined to defend our republic, against all attacks, we hereby declare our firm desire to make peace as soon as it is possible to do so with the assurance that its conditions will secure to the working-class of Hungary the possibility of a livelihood, a peace that will enable us to live in accord and in harmony with the peoples of the earth, and above all, with our nearest neighbors.”

The determination expressed in this proclamation, to unite the forces of the Hungarian republic with those of Soviet Russia were put into immediate practice. On the 22nd of March the Hungarian Soviet Republic was directly connected with the Russian capital, and the following interesting exchange of messages ensued:

“The Hungarian Soviet Republic requests Comrade Lenin to come to the wire.” After 20 minutes the following answer came from Moscow: “Lenin at the apparatus. Will you connect me with Comrade Bela Kun.”

The following reply was sent from the Budapest station: “Bela Kun is at present unavoidably detained in the Commissariat. Representing him at the wire is Ernest Por, member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. The Hungarian proletariat, which last night assumed the dictatorship in the Hungarian nation, sends greetings to you as the leader of the international proletariat. Through you we send to the Russian people the expression of our revolutionary solidarity and our greetings to the Russian proletariat…Comrade Bela Kun has been appointed People’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs. The Hungarian Soviet Republic requests a defensive and offensive alliance with the Russian Soviet Government. With weapons in hand, we will defy all enemies of the proletariat. We request immediate information as to the military situation.”

At 9 P.M. the following reply came from Moscow: “Here Lenin. Submit my heartfelt greetings to the proletarian government of the Hungarian Soviet Republic, and particularly to Comrade Bela Kun. I have just submitted your message to the Congress of the Communist Party of Russia. It was received with unbounded enthusiasm. We will report to you the decisions of the Moscow Congress of the third Communist International as rapidly as possible, as well as the report concerning the military situation. It is absolutely necessary to maintain permanent wireless connections between Budapest and Moscow. Communist greetings. Lenin.”

The following message which was received by the office of the Swiss Social Democratic Party on the 29th of March shows how wholeheartedly the new Hungarian government has entered upon its chosen course:

“As soon as we gained the power necessary to put our program into action, we proceeded without waiting a moment. Already we have felled the impregnable walls of the capitalist fortress, blow upon blow. The fetters of wage slavery are torn into a thousand shreds; and at the same time we have begun the creation of a new world. Industrial life is taking its normal course, indeed it is already functioning more smoothly than before. Only the parasites have been abolished, their life of idleness is at an end. What the country possesses of mental and physical energy has been put to work. Production and transportation are entirely in our hands. All supplies have been confiscated and will be in part equitably distributed, and partly used as material, with which we will build up the Communist organization of production. All those legal fetters that were invented by Capitalism for the oppression of proletarian existence have been swept away. Air, light, cleanliness, at one time the exclusive privilege of the children of the bourgeoisie, have been placed within the reach of the children of the proletariat. Theaters, hitherto exclusively the – possession of the wealthy class, are being encouraged to devote themselves, more than ever before, to the propagation of a higher art, and have been opened to the proletariat. The Press, that mighty weapon of Capitalism, has been pressed into the service of the movement for a better future. Joyously, great masses of the proletariat are crowding into the Red Guards, ready to defend their liberation from capitalist slavery with their hearts’ blood. Heads up, brothers! The Gotterdammerung of capitalist society has come. The hour has struck for the expropriation of the expropriators of the world.

“Bela Kun, People’s Commissary.”

* * *

Sparse as are the reports that reach us from the new revolutionary government, they all indicate that the above sweeping statements are based upon actual fact. In Budapest the revolutionary government has appointed a commissariat for housing problems, which has gone at once to work not only to formulate, but to put into immediate practice a thorough-going system of housing reform. According to the conditions laid out by this commission no single individual shall for the present have the right to occupy more than one room with the necessary appurtenances. All larger domiciles have been investigated and assigned. Rents have been ordered reduced, particularly for the cheaper houses, where the reduction has aggregated approximately 20 per cent. The socialization of the financial institutes of the country is already well under way. The right to draw upon bank deposits has been materially restricted. The suffrage has been extended to all men and women over 18 years of age who are doing socially useful work, or who are employed in home work that furthers the labor of those who are employed in socially useful occupations. All persons who insist upon living without labor are excluded from participation in political affairs.

The Hungarian socialist republic has been fortunate in that it has been able to profit by the lessons that the Russian revolution learned only after long and often bitter experiences. Where our Russian comrades were forced to grope blindly, step by step, to find their way out of the maze of capitalist mismanagement that surrounded them on every side, their Hungarian followers are working, with eyes that can see and weigh the consequences of each act, along a well defined course of action. One of the most interesting signs of the new spirit that pervades the Hungarian revolution is the union of the two wings of the social democracy, a union not only for the purpose of conducting the affairs of state, but an actual merging of identity of the two organizations. According to socialist press reports “the Communist Party has ceased to exist and will henceforward be known, together with the old ‘majority’ Party, under the name of ‘Socialist Party.’ ” In Russia the revolution was seriously hampered by the counter-revolutionary opposition of the Mensheviki and Social Revolutionists of the Right. Only now, when the determined resistance of the entire Russian nation to the invasion of Allied forces has made further support of intervention a suicidal policy to pursue, after two years of persistent effort have shown that the social revolution in Russia has come to stay, only now it appears that these elements are prepared to support the Bolshevik regime. The course of the Hungarian revolution will be the easier for this lesson, because the men and women of the reactionary wing of the Hungarian socialist movement were, if anything, more conservative than the Russian Mensheviki, and yet they were immediately ready to join the forces of the Communist movement, once it was pushed into power.

But not only the proletariat has learned. The bourgeoisie, too, has profited by the example of their fallen Russian brethren, and have, up to the present time, refrained from all counter-revolutionary demonstrations. According to the reports that reach us from Hungary they are leaving the inhospitable confines of the new proletarian republic as fast as possible, and to all appearances, the proletariat is more than willing to see them go. It is possible, therefore, that Hungary will prove the truth of Lenin’s contentions, when he says that the Red Terror, that has aroused such a storm of indignation against the Russian Bolsheviki, is by no means an inseparable accompaniment of the dictatorship of the proletariat. There has been no Red Terror in Hungary, because there was no White Terror; because the Socialist movement, in its entirety, stands behind the Communist program of socialization, because the Hungarian bourgeoisie does not dare to engage in counter-revolutionary propaganda in the face of a united proletarian opposition; because, finally, the Allied nations and the smaller nations, whose capitalist rulers may desire to foment counter-revolutionary activity by means of armed invasion, will do so only at the risk of carrying the conflagration into their own lines.

As we go to press, the cable brings the news of a victory of the “Reds” in Vienna. With each new victory of the proletarian movement of the world, the “dictatorship of the proletariat” loses some of its terror. The proletarian revolution, i.e. Bolshevism, has ceased to function as bugaboo, as a horrible example in the interests of a capitalist world. It has become the hope and the highest achievement of the revolutionary proletariat.

The Class Struggle and The Socialist Publication Society produced some of the earliest US versions of the revolutionary texts of First World War and the upheavals that followed. A project of Louis Fraina’s, the Society also published The Class Struggle. The Class Struggle is considered the first pro-Bolshevik journal in the United States and began in the aftermath of Russia’s February Revolution. A bi-monthly published between May 1917 and November 1919 in New York City by the Socialist Publication Society, its original editors were Ludwig Lore, Louis B. Boudin, and Louis C. Fraina. The Class Struggle became the primary English-language paper of the Socialist Party’s left wing and emerging Communist movement. Its last issue was published by the Communist Labor Party of America. ‘In the two years of its existence thus far, this magazine has presented the best interpretations of world events from the pens of American and Foreign Socialists. Among those who have contributed articles to its pages are: Nikolai Lenin, Leon Trotzky, Franz Mehring, Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg, Lunacharsky, Bukharin, Hoglund, Karl Island, Friedrich Adler, and many others. The pages of this magazine will continue to print only the best and most class-conscious socialist material, and should be read by all who wish to be in contact with the living thought of the most uncompromising section of the Socialist Party.’

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/class-struggle/index.htm