Louis Duchez, son of an exiled Communard, on France’s C.G.T., part of the global wave new industrial unions that challenged the political and organizational conceptions of much of the left before World War One. Duchez was a proletarian intellectual raised in the coal mines of Ohio; a poet, labor organizer, journalist, and revolutionary Socialist who assumed a leading role in our movement during his too short life, dying at just 27 in 1911.

‘The General Confederation of Labor’ by Louis Duchez from The International Socialist Review. Vol. 10 No. 9. March, 1910.

INTRODUCTION.

IN view of the tremendous interest that is being taken in industrial unionism the last year, not only in the United States by throughout Europe, it is highly important to the working class of America to know the progress made by the workers of France, where, doubtless,” the revolutionary union movement has made greater progress than in any other country.

In regard to the revolutionary unions of France and Italy George D. Herron wrote from Europe in the International Socialist Review a few months ago: “A turn of the hand might place the French government—and in two or three years the Italian government—in the hands of the revolutionary unions of the syndicalists.” He further says: “The syndicalist revolutionary unions are compelling things from respective governments, and are achieving results for the working class beyond anything that Socialist members of parliament have ventured to demand.”

The following article is the substance of a pamphlet entitled, “La Confederation Generale du Travail,” by Emile Pouget—one of the foremost of revolutionary unionists in the world to-day—and published by the “Library of Political and Social Sciences” of Paris. I have attempted to condense this booklet of 65 pages as much as possible, outlining the structure of the Confederation, the tactics employed and something of the results attained so far. The pamphlet is a history of the organization up until 1908.

THE ORGANIZATION.

The General Confederation of Labor was organized in 1895 at a syndicalist congress held at Limoges, which is perhaps the most Socialistic center in France. It is the most dominant labor organization, both in numbers and in spirit, in France to-day. It is not affiliated with any political party.

At its base is the syndicate, which is an aggregation of workers in different crafts and different kinds of employment. Second, the Federations of Syndicates and the Union of Syndicates; and, lastly, the General Confederation of Labor, which is an aggregation of federations. In each degree the autonomy of the organization is complete.

The structure of the General Confederation is not a cut and dried affair. Its development has been remarkably spontaneous. First the syndicates developed and as the need of greater power became apparent, the federations sprung up, and, lastly, the General Confederation. No one is excluded from membership because of religious, philosophic or political views, so long as he or she is a bona fide wage earner.

It has only been since 1884 that the law permitting the existence of syndicates was enacted. Long before that, however, they were in existence. Because they were growing in power, the State sanctioned what it could not prevent. In 1884 the State, after abolishing legislative prohibition in regard to them, enacted another law requiring them to deposit their constitution and by-laws and the names of all their officers in the mayor’s office of the place in which the syndicate existed. It also stipulated that the officers shall be Frenchmen. Everything was done by the State to curb their influence and if possible to destroy them. But they developed without regard to legal requirements; and, as a result, a general feeling of distrust among the syndicalists in regard to the State’s attitude toward them prevails. It is needless to say that they had a fierce struggle to gain a foothold.

The Confederation is founded upon a knowledge of the class struggle. It is essentially a fighting organization. Solidarity and the resistance of capitalist exploitation are its watchwords for the present-day battles of the workers. But it aims at greater things. One of the principles which the Confederation teaches is that the embryo of the new society is the economic organization of the workers. The Confederation presses forward with that end in view. It holds that there is no harmony between itself and the State, and resists the latter to the extent of its power. The Confederation has passed that stage where it can be brought in harmony “with the State and capitalism. In fact, from its very foundation 15 years ago, revolutionary principles were taught.

Another trait of the Confederation which characterizes it as a revolutionary organization is the fact that institutions of mutual help play no part within the organization. There are, however, co-operatives of different character carried on outside the organization in general. Everything within the organization is avoided that tends to hamper its combative spirit. In this respect the French syndicates differ radically from the trade unions of England and Germany.

In the Preamble of the Confederation, after explaining the class character of modern society and the futility of expecting the State to help the workers even if it desired to do so, it urges a class organization of the workers on the economic field. “Only through this form of organization,” the Preamble states, “will the workers be able to struggle effectively against their oppressors and completely abolish capitalism and the wage system.”

The governmental statistics state that there are 5,000 syndicates in France. Of this number over 2,500 are affiliated with the Confederation. They are called the “red” syndicates, because of their revolutionary spirit and aggressiveness in all lines of working class activity in opposition to the public powers and the bosses.

Besides these there are about 900 syndicates not affiliated with any organization that are “red” in character. So out of the 5,000 syndicates about 3,400 are revolutionary and endorse the Preamble of the Confederation. The remaining 1,600 syndicates are what are called “yellow.” They act upon the principle of the harmony of interests between capital and labor. Many of them have been organized by the employers and are officered by foremen, “straw-bosses,” etc. Like the recent movement of the clergy of France to organize Catholic unions, which the “reds” have labeled “green” syndicates, the aim of those in charge of the “yellow” syndicates is to sidetrack and prevent the revolutionary unions from gaining ground. But their efforts are futile, as we have seen. We learn that these “yellow” syndicates are decaying and the rank and file of their members are being carried into the ranks of the “reds” by the increasingly revolutionary activity of the latter.

The syndicates are affiliated with the Confederation in two ways. First, those of different occupations are assembled in one city or region; second, the syndicates of the same occupation or industry over the whole country. The first groupments are called the “Bourses du Travail” or Unions of Syndicates; the second the National Federations. The latter is more the plan of the Confederation. The former is more popular, however, which is doubtless due to the fact that the “Bourses du Travail” are what would be called temples of labor and were built by the different cities for all classes of workers, organized and unorganized, to meet in to discuss their grievances. In this connection it is well to note that the object of the municipalities in building these temples of labor was to bring the unions more under the control of the States. In certain instances ordinances were passed governing them which were diametrically opposed to the organizations which they claimed to uphold, and in many cases the workers have refused to meet in these Bourses. The tendency now is to break away from them in order to keep clear the class character of the syndicates.

There are 135 “Bourses du Travail” or Unions of Syndicates affiliated with the General Confederation of Labor, taking in about 2,500 syndicates, 1,600 of which have now rallied to the National Federations. The Bourses du Travail tend to keep the workers divided, still it is through them principally that the workers have gone to the National Federations.

The “Bourses du Travail” are performing an important function in freely assisting those out of employment to secure the same and in furnishing legal advice and transportation from one point to another to the best of their ability. As a rallying ground and avenue of propaganda they have meant much.

Since the congress of Amiens, 1906, however, the federations of existing trades, without being eliminated, are admitted to the Confederation as federations of industries.

A remarkable spirit of solidarity and democracy prevails throughout the Confederation. Pouget says: “The centralism which, in other countries, kills labor’s initiative and hobbles the autonomy of the syndicates, disgusts the French working class; and it is that spirit of autonomy and federalism (initiative and solidarity) and which is the essence of the industrial society of the future, which gives to French syndicalism a profound revolutionary phase.”

There are 60 Federations affiliated in the Confederation and three of what are called National Syndicates. Nearly all the federations publish a monthly paper which is distributed free to all the respective members. Then there is the national organ, “The Voice of the People,” which is published weekly.

The 1906 statistics of the Confederation showed that there are 205,000 members in the Confederation. The workers of the building trades are the most numerous. They number 210 syndicates. The printers and binders and the metal and machinery workers number each 180 syndicates; the textile workers 115; leather workers 64; agricultural workers, which are composed principally of wine growers, 100; wood choppers 85; moulders 79; besides several other smaller groups.

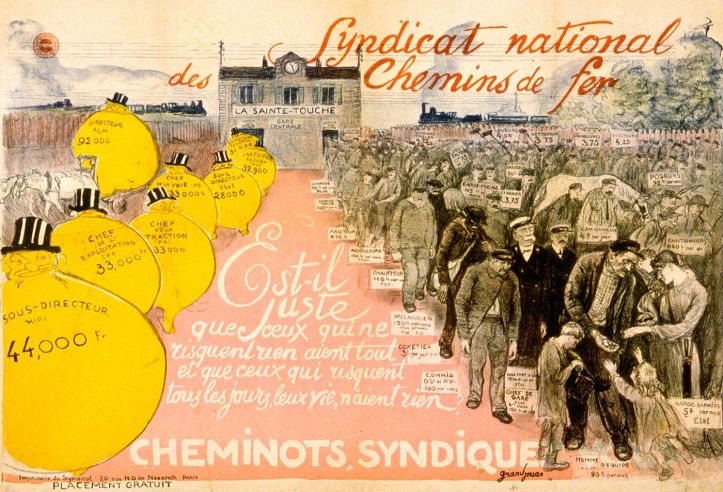

The term “National Syndicate” was given to the railroad workers, which comprises 178 sections. They have had to fight the hardest for the right to organize. The State only consented to their organizing and joining the Confederation when it could not avoid it. But the struggle has made them the most militant of all the syndicates. The same thing is true of the mail carriers and the school teachers. The latter two, however, regardless of State intervention, are getting together and they are manifesting a militant spirit in proportion to the pressure of the State upon them.

The Confederation is not an organization of authority and direction; instead, it is one of co-ordination. It aims to bring into harmony the various groups affiliated with it for the general welfare of the working class. The ideal proclaimed and followed is “the entire elimination of the forces of oppression, established by the State and the forces of exploitation manifested by capitalism.” Its grounds for neutrality in politics are that the wage system cannot be abolished and still retain the political State. It aims at a social reconstruction where the workers will have direct say in the exercise of their labor power through an organization of the workers, with its foundation laid in the industries and not upon the institutions of official capitalist society.

The fact that the Confederation does not take part in parliamentary life does not mean that it does not take a stand against the State. On the contrary, as is well known, its position in that respect is well defined. Its opposition to the State increases and intensifies as its power grows. True to the Socialist philosophy, it holds that all power is economic and that the proletariat in order to overthrow capitalism must exercise its economic power along the line of the industrial organization of capitalism in order to effectively win concessions now and form the basis of the new society when capitalism is to be overthrown. The political action of the Confederation is exercised in the form of exterior pressure, and, as we will show later on, is the real and effective method of the workers in compelling legislative favors.

The National Federations and the “Bourses du Travail” each form a section of the Confederation and officers are elected from each, composing a Confederal Committee. This Confederal Committee harmonizes the work of the organization, directs the general action and carries on an active propaganda. The treasury of the Confederation is comparatively insignificant. In this respect its aims are limited to the meeting of administrative and propaganda expenses. In case of strikes or mass movements it depends, principally, upon assessments and voluntary contributions. In a large degree the strength and revolutionary character of the Confederation is due to the fact that there is no honey jar at the national headquarters to which self-seeking individuals gravitate. Conventions or congresses are held every year, in some cases every two years. The Confederation proper meets every two years.

It has recently been estimated that the Confederation numbers about 300,000 members and is just now gaining that momentum which is destined to make it the ruling power in France.

TACTICS.

As stated, the method in dealing with the hostility of capitalist institutions is that of exterior pressure—what is commonly known as direct action. Its same attitude holds good in regard to religious and philosophic conceptions. The prime object is to get the workers into the “red” syndicates. This done, it knows that in associating and struggling with others who have like economic interests, they will not only be carried on by the momentum of the organization, but they will at the same time develop their class knowledge along all lines. In this respect we see that the Confederation applies the modern secret in education—the inductive method. It may well be characterized in the words, “Learning by doing.”

In this connection it is well to note that the methods of Direct Action do not necessarily imply violence. On the contrary, they may mean the reverse, as has been shown in numerous cases in France. Direct Action is the dominant trait of French syndicalism. The common method in opposing State hostility is that of mass uprising in the form of propaganda meetings and demonstrations for some particular thing, as for instance, the eight-hour day in May, 1906, or to compel the enforcement of some law in their favor. The common method of fighting the employers are the strikes, the boycott, demanding the label and the sabotage.

Hairsplitting and squabbles now find little room in the Confederation; there is too much revolutionary activity in the movement to give an opening to those who live by talk. Pouget says that if the spirit of State intervention were to enter the Confederation it would be a good police in favor of the exploiters and would lead the organization toward conservative ends. That fear has left the militants of the movement, now, however.

In order to parliamentise the action of the syndicates the Superior Council of Labor (the Civic Federation of France) was established. Its function, as Pouget states, is “to chew working class laws into parliament”; in short to attempt to absorb the revolutionary energy of the workers into “hot air.”

The avenue of the strike has been the most effective method of organizing the “red” syndicates. The Confederation has discovered that and every opportunity is taken. It has also been discovered that wherever a ray of confederal influence manifests itself during a strike, a profound revolutionary aspect is noticed. A victorious strike is a partial expropriation of the instruments of production, and, under the guidance of confederal influence, has sharpened the revolutionary appetites of the workers to a remarkable degree.

The declaration of strikes, in most cases, is left to the initiative of those interested. In the Constitution of the Federation of Leather Workers we read: “All syndicates before declaring a strike shall notify the Federal Committee. The Federal Committee, without having the right to oppose a declaration of strike, may make objections if judged necessary.” In some cases, however, the declaration of a strike rests with the Central Committee; as, for instance, with the printers and bookbinders.

The use of the boycott and the demand for the label are well known—though they have amounted to very little. The “sabotage” (following strictly the bosses’ rules, turning out inferior work, etc.) has been used effectively in compelling the bosses to give in and still remain at work. Of course, back of all these methods is the organized and disciplined power of the workers.

It is in the mass movements, however, that the Confederation has found its greatest stimulus. In the midst of them the organization grows tremendously, revolutionary spirit blazes and proletarian power is impressed directly upon the minds of the workers. One of the prime objects of the Confederation is to be ready for these mass movements, encourage the spirit as much as possible, welding, when the interest is at white heat, the workers into a solid body. It holds that every mass movement, whether manifested in the form of a general strike, general agitation for the enforcement of some law or in the form of propaganda demonstrations, undermines the faith of the workers in existing institutions, tears away the veil and exposes the class character of capitalist society, and at the same time develops faith and self-reliance in the minds of the workers in their own organization.

One of the most characteristic of these mass movements took place in 1903-1904 against the employment agencies. After two months of increasing agitation the Confederation compelled the government to suppress them. It did in two months by united effort what could not be done in 20 years before through petitions and parliamentary wrangling. (Those who have been following the Spokane fight for free speech against the employment agencies can realize what the suppression of these employment agencies meant to the French workers.)

It was the same kind of a mass movement applying exterior pressure which broke out after well-laid plans the 1st of May, 1906, that compelled the government to enact the eight-hour law and the weekly rest day.

It is important to remember, too, that there is nothing like these mass movements aimed against the State to send the chills up the spines of the middle class and win their good will, for they are generally hit the hardest where a good blow counts—in their pocketbooks.

Lastly, all these mass movements of more or less intensity are but preparations for the final charge before the revolutionary change—the general strike. All previous revolts in whatever form are but preparations for this one. It will be the decisive blow. The refusal, in this connection, to continue production of the capitalistic plan is not purely a negative move. It is concomitant with taking possession of the instruments of production and organizing society on the co-operative plan, which is effected by the social cells of the new society—the syndicates. Sometimes strikes are generalized to one federation (such as the last strike of the Parisian electricians) and sometimes they are generalized in certain localities, such as took place in Marceille, Saint-Etienne, Nante, etc. At any rate, they are but partial catastrophes or preliminaries of the general expropriation of capitalism.

So it can be seen that the Confederation is not merely an organization with aims for the immediate betterment of the workers, but it is being impressed upon the proletariat of France that it is the very foundation of the new society of which they will have direct control. It is seen, also, that with this final blow the present society is dislocated, ruined, and that the few useful functions of the State and municipalities will be transferred to the corporate federations in the syndicalist unions—where the centers of cohesion will find a new base. The realization of this end will be the Industrial Democracy which Utopians and scientists have said so much about.

RESULTS.

The benefits the French workers have received through this economic and class organization can only be approximately judged. The great psychological benefits which will mean so much for the Social Revolution we can only estimate by the revolutionary activity of the workers of France so far. We will dwell upon the material results.

In the ten years between 1890 and 1900 the percentage of successful strikes was 23.8; partial “victories, 32.2; lost, 43.8. During these ten years 56 strikes of every hundred turned out favorable to those interested. It is also shown that about 61 per cent, of those engaged were in one way or another benefited by the conflicts.

During the following four years (1901-1904) the results of 2,628 strikes effecting 718,306 workers are as follows : 644 strikes, 24 per cent, won; 995 strikes, 38 per cent, partial victories; 989 strikes, 38 per cent. lost. So it is seen that 62 per cent, of these strikes turned out favorable to the workers engaged. The statistics given by the strikers also show that 79 per cent, of those engaged in the conflicts were benefited in one way or another. In what country have the workers made so good a showing?

But that is not all. The statistics of the strikes of 1906 make a better showing. Out of 830 strikes in that year 184 were entirely won, 361 partially successful and 285 lost. One hundred and forty-seven thousand eight hundred and eighty-eight participated in the 830 conflicts. The statistics show that more than 83 per cent, of those who engaged in the conflicts were in one way or another benefited. The increasing progress is, indeed, noticeable.

Also, in 1905 out of the 530,000 strikers that demanded a decrease of the hours of work, nearly 40 per cent, were entirely successful, 51 per cent, were partially so and only 9 per cent. lost.

All over France syndical action has benefited the workers. In the center of France before the organization of syndicates the woodchoppers were working 15 and 16 hours a day. To-day they work 10 hours and have increased their wages from 40 to 50 per cent. Besides, they have abolished the pooling or contract system which was one of the worst things they had to deal with. The wine growers after a series of strikes in 1904-1905 won an increase in wages from 25 to 30 per cent, with the work day reduced to 6 and 8 hours a day. In 10 years the match workers (males and females), which have now a very solid organization with 90 per cent, of all the match workers in the organization, have raised their wages 50 per cent., with the nine-hour day. The workers in the mail system and those of the telegraph and telephone lines have obtained through syndical action the eight-hour day and an increase of 30 per cent. The workers in the government navy yard after three years of hard fighting have the eight-hour day and a large increase in wages, also. The bakers, barbers and nearly all other workers in the public service department have received corresponding increases in wages and better working conditions. Those of the building trades have made remarkable progress also.

But the mass movement for the eight-hour day which burst through the crust the first day of May, 1906, is the crowning glory of the Confederation so far. It has been the greatest thing the Confederation has done to solidify its forces and give the working class of France a taste of proletarian power.

At the 1904 congress of the Confederation the resolution was passed. The date of action was set for May 1st, 1906. For eighteen months after the congress adjourned an intense educational propaganda was kept up in order to show the workers the tremendous power of better working conditions and the higher wages the eight-hour day meant in itself. All forces were centered to this one end.

When the day arrived workers all over France knew it and everywhere when the eight hours were up from border to border workers picked up their buckets and went home. Of course there were great struggles, and in many places awful defeats. These things are expected in the class war. But there were more victories. Not only victories direct from the bosses but the government was compelled to pass the eight-hour law, which is supposed to be in force all over France. When the Confederation grows in power not only will the eight-hour law be enforced, but a still shorter work day. The agitation during the eight-hour mass movement did one thing, which alone is worth all the effort put forth, and that was to teach the workers that the short-hour day and a small individual output mean, in themselves, higher wages. Before the eight-hour movement the general rule was that the man who did the most directed the pace. It has now changed. The man who does the least is the pace setter. Individual production has decreased 20 to 25 per cent. And we see this substantiated by the fact that the unemployed army of France is smaller in proportion to its population than in any other country in the world.

These are some of the concrete material results gained by the workers of France through their class organization in the industries. It is, however, the potential power of the Confederation and the great hope it inspires in the proletariat of France with reference to the Social Revolution that interests us most. Even with its comparatively small numbers it has done wonders. Its revolutionary vibration has penetrated every institution of capitalist society in France. It has won the respect and support of a large part of the standing army, as was seen a few years ago when a whole regiment threw down its guns and refused to shoot down the strikers of the vineyards. Even the prison guards of a large number of institutions have banded themselves into “red” syndicates, reducing their hours of labor and raising their wages. We learned recently, too, that a large number of the Parisian policemen have also formed a syndicate. Premier Briand is worked up over it and in an address before them some time ago said that he approved of a fraternal organization among them for mutual assistance, but it was out of their sphere to affiliate with a “militant union,” meaning, of course, the Confederation. It is stated by several militants that already a large percentage of the “slugging committee of the capitalist class” may be “counted upon”—when something big happens. But they are not depending on that. They know that if they have the economic power all other power is theirs.

Another feature in connection with the Confederation which is an indication of remarkable solidarity, is the action of strikers in sending their children, in many cases hundreds of miles, across the country, where they are kept in the homes of other workers who are employed, while the parents stay at home and do all in their power to win.

CONCLUSION.

We have traced the development of the Confederation from the syndicates upward. We have shown that while its growth was spontaneous it was natural; that as the pressure of economic conditions pointed out the need of greater working class power, that power developed, and that the syndicates assembled into federations and the federations formed the Confederation. We have also shown that the tactics of the organization were first, last and always those of Direct Action; that its methods of dealing with the hostility of the State were those of exterior pressure; that it holds that parliamentarianism weakens revolutionary fibre, tends to prevent the growth of solidarity and blurs the line of the class struggle; that it has remained neutral to political, religious and philosophical doctrines, holding that the prime object of the revolutionary movement is to get the bona fide wage earners into a class organization on the economic field, resting assured that they will think right and act right in their collective associations under the confederal influence.

We have further shown that these tactics of Direct Action have won; that they have won concessions from the capitalists of France that are not equaled in any other country; and that they have but sharpened the appetites of the workers for more.

Lastly, we have shown that while the Confederation and its “red” syndicates carried out a “constructive program,” fruitful, indeed, with “immediate demands” that were granted in most instances, it carries with it and keeps ever in sight its ultimate aim—the Co-operative Commonwealth. Yea, it is already laying the base for that co-operative commonwealth—the new society. We have shown that the Confederation is actually preparing itself and teaching its membership for the management of industry when capitalism is overthrown. In the language of the Preamble of the Industrial Workers of the World—a revolutionary union of the United States with principles and tactics identical with the General Confederation—it is “forming the structure of the new society within the shell of the old.”

Now, the revolutionists of other countries may ask the question why it is that the proletariat of France has developed a revolutionary movement superior to those of the other capitalist nations. Many reasons, perhaps, could be offered. We will suggest two. First, there is the French blood. The Celtic race has always been a fighting race. And France is universally known as “the classic land of revolt.” Then there is its geographical status and climate. It is about half agriculture, half industrial, so has had the mineral resources in order to develop into a big industrial nation, splendid outlets to other countries, and a climate and traditions that attract its own and other peoples. France, like the United States, can live within itself.

Then the French nation has gone through many political changes, in which the working class has painted the streets with their own blood. These “revolutions” and “communes,” brutal and terrible as they have been, have been lessons to the proletariat of France. It has been taught by cruel experience that mere shifting of political scenes will not benefit it; that it has been fighting the battles of the nobility, the capitalist class, the middle class and all the elements of the old society long enough. It is now going to fight for itself, taking no quarter, and conscious of its social mission. Hence the General Confederation of Labor.

The proletariat of France is carrying the torch of the Revolution in Europe.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v10n09-mar-1910-ISR-gog.pdf