The still largely unknown story of the United States’ role in the suppression of the Paris Commune through the hugely ambitious Minister to France, Elihu B. Washburne.

‘When Counter Revolution Wins’ by Henry Cooper from New Masses. Vol. 15 No. 3. April 16, 1935.

Documents of America’s Role in the Paris Commune

(The Paris Commune was the first workers’ government ever established. It arose in the midst of the Franco-Prussian War, when the German army was closing in on the French capital. The Emperor Louis Napoleon had fled at the approach of the enemy and on September 4, 1870, France was declared a republic. That “monstrous gnome,” Thiers, together with other bourgeois politicians, stepped into the executive offices. But when the Prussians neared Paris, the “saviours of France” followed Napoleon’s example and fled. Incensed by this betrayal, the workers of Paris seized power in their own name. On March 18, the Commune was proclaimed. For seventy-one eventful days it maintained power in behalf of the working class, holding back the besieging Prussians on the one hand and on the other fighting the counter-revolutionary troops of Thiers, who had crawled back to Versailles and established his headquarters there. After a heroic defense against the overwhelming reactionary onslaught, the Communard lines began to break on May 22. The Versailles troops entered Paris and advanced slowly on the nerve-center of the Commune, every step contested by the workers. Then began “Bloody Week,” when thousands of working men and women of Paris, unarmed, were lined up in front of open graves, against walls and along river banks, and raked down by machine-guns. That week the Seine ran red with blood. It is estimated that from thirty to forty thousand Parisian workers were massacred. The Commune finally fell on May 28. The document discussed in this article throws new light on the last days of the Paris Commune, and reveals the important Paris Commune, and reveals the important part played in its downfall by the American Ambassador to France–a comparatively unknown phase of that historic event.–THE EDITORS.)

WHEN Elihu B. Washburne was sent to Paris in 1869 by the newly-elected President, U.S. Grant, it was a reward for his leading part in placing the General in the White House (and, incidentally, ushering in a regime of graft unparalleled up to that time). Before leaving for France he occupied, on his own insistence, the post of Secretary of State in Grant’s cabinet for one week. With characteristic political shrewdness, he had sensed the added prestige this nominal honor would bring abroad and also, perhaps, its potential value in the campaign for the presidential nomination he waged some years later, upon his return to the United States.

Washburne had been in Paris little more than a year, glorying in the endless round of brilliant and costly functions at the court of Napoleon III, when the Franco-Prussian War broke out. He saw pompous Louis Napoleon flee when the Prussian army marched on Paris. He saw Thiers and his unscrupulous henchmen leap to the head of the government when the republic was declared in September, 1870. He saw the Thiers government betray the people and follow the erstwhile emperor in flight when the Prussians knocked at the gates of Paris. He saw the angered workingmen and women take their places at the abandoned breastworks and fight the invaders to a standstill. He saw them seize control and set up their own government in the name of the working class of France. He saw those same workers restore order to a chaotic, demoralized capital, and administer their affairs so efficiently as to wring a grudging admiration from even their bitterest foes.

Washburne hated that workers’ government with all his heart. He understood its universal implications. universal implications. He knew that this government, functioning more efficiently than any of its predecessors, would serve as a model for the working class throughout the world, if permitted to stand. Its very existence was a living refutation to the slander circulated then (as it is now by Hearst and others) that the working class is the least capable of ruling. He was keen enough to sense the danger, not only to the ruling class of France, but to his own class back home. He was determined to do all in his power to help destroy the Commune. As the only foreign minister retaining his headquarters in Paris after the Commune was proclaimed, he enjoyed a strategic position in working toward that end.

Like his notorious prototype of a later generation, David R. Francis, U.S. Ambassador to Russia during the Bolshevik uprising, Washburne did everything in his power to discredit the revolution, and to aid international intervention. While soft-soaping the Commune leaders with protestations of sympathy, he sent out false “atrocity” stories, both in an official and unofficial capacity, exceeding even the vituperation of the world capitalist press, aghast at the spectacle of a working class seizing power and wielding it effectively. Although he rode at will throughout Paris during the whole course of the workers’ regime, and witnessed with his own eyes the peace, quiet and orderliness that characterized the city under the Commune,1 he insisted, in his official dispatches and magazine stories in American periodicals, on describing it at all times in terms of “Communist excesses, cruelty, anarchy, massacre and incendiarism.”

In the meantime, he actively intrigued with the reaction in its efforts to strangle the workers’ revolution. While enjoying every privilege and courtesy conferred upon him by the Commune’s leaders, (who mistakenly trusted him, regarding the government he served in the light of the revolutionary traditions of 1776. They failed to realize that that government had no sympathy with its own aims, that it was intent not on encouraging a new order, but on conserving an old one) he acted as a secret spy of the Thiers government. He was a convenient go-between of Thiers and his agents in Paris, and relayed vital information to him throughout the existence of the Commune.

To Washburne is attributable much of the frightful tragedy that attended the last days of the Commune; on his head rests the blood of thousands of the victims who fell in the reactionary wave of “Bloody Week” and after. It was he who, by a stroke of cold-blooded treachery, lowered the guard of the Commune at the very moment when alertness was needed most, and thus prepared the way for the unbridled white terror that was to follow.

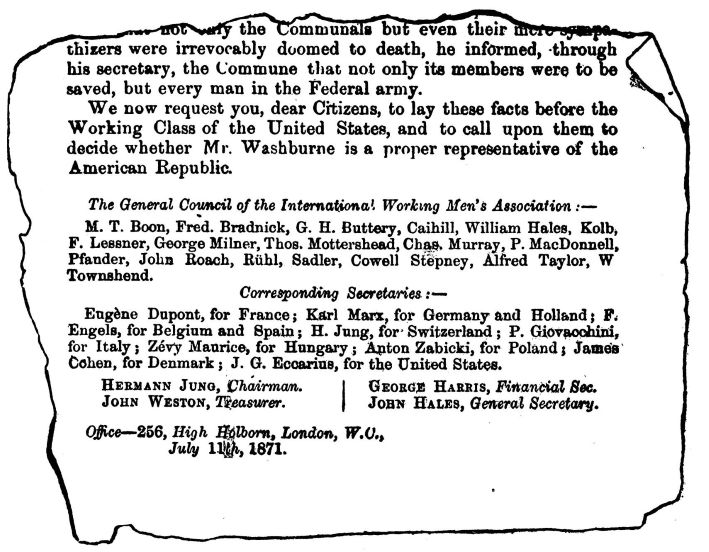

Washburne’s ugly role in the last days of the Commune, hitherto overlooked by historians, is revealed in a document sent by the International Workingman’s Association (the First International) from its headquarters in London to its American section in New York following the fall of the first proletarian republic. The writer stumbled upon this communication in a long-forgotten bound volume of pamphlets at the New York Public Library. The charges and revelations it contains are of no little interest and importance for us today. Large sections of the American working class–even the most advanced sections are still inclined to look upon the historic Commune as an event isolated from and unrelated to the United States. Here, through this document, stands revealed for the first time, in this connection, the American link in the chain of international solidarity of the imperialist countries in their common war on the proletariat everywhere. The U.S. government is clearly implicated, for throughout his whole active part in the fight against the Commune, Washburne was in constant communication with the Secretary of State, Hamilton Fish (grandfather of the present Ham). It is inconceivable that the Minister to France could have carried out the treacherous activities charged to him by the International without the implicit sanction of his chief.

The International’s communication is in the nature of a protest against Washburne, reinforced by statements of a participant and an eye-witness in the Commune. It ends with the request that its United States section familiarize the working class of America with the duplicity of the agent of American imperialism in Paris. Of the two statements affirming the charges against Washburne, one was made by Mr. Robert Reid, a liberal correspondent for English and American daily newspapers during the siege of Paris and the Commune. The other is a deposition by a member of the Commune.

During the last weeks of the Commune’s existence, Reid witnessed the barbaric cruelties of the reactionary troops under Thiers, whose slow advance against the barricaded Communards was strewn with the corpses of captured workers lined up and shot without even the formality of a court-martial. Shocked by these incredible horrors, Reid naively called upon Washburne to intercede for the helpless victims in the name of humanity and the government Washburne represented. in this respect Washburne’s position in proved particularly propitious. As the only foreign envoy remaining in Paris during the Commune and one who was an active agent of the Versailles government, any effort he might make in behalf of the workers would necessarily have carried weight. But Washburne soon gave Reid to understand that neither he nor his government was interested in preventing the massacre of tens of thousands of workers. Reid’s deposition notes the haughty arrogance and cold brutality with which Washburne punctuated his rebuffs.

On May 24, 1871, in a conversation with Reid carried on before witnesses, Washburne told him “with the air of one who knows the truth of what he is saying” that “All who belong to the Commune, and those that sympathize with them, will be shot.” (Italics Reid’s.)

And here the duplicity of the agent of the American government is shown in all its hideousness. For on the very day (May 24) that Washburne informed Reid in a semi-official capacity that all Communards and their sympathizers were to be massacred, he sent his secretary to the headquarters of the Commune with an offer of intercession on the part of the Prussians beleaguering Paris, for which act he claimed he had full authorization. The terms of the intercession, as laid down by Washburne, avowedly acting as an intermediary of the “neutral” Prussians, were as follows:

1. Suspension of hostilities (between the Communards and the Versaillese troops headed by Thiers).

2. Re-election of the Commune on one side, and the National Assembly on the other.

3. The Versaillese (reactionary) troops to leave Paris.

4. The National Guard (Communards) to continue to guard Paris.

5. No punishment to be inflicted on the men of the Federal army (serving the Commune).

This proposal was accepted by the Commune in good faith. (As in other instances, the Commune reposed too much trust in representatives of the bourgeoisie, a weakness for which it was to pay dearly. Washburne, it should be noted, was given carte blanche throughout Paris by the Commune during the whole course of its reign, at a time when–as was subsequently made clear–he was acting as a willing tool of the Thiers government, sending it reports on developments regularly, etc.)

The Paris Commune almost immediately acted upon the proposed agreement, and in the ensuing two days sent deputations to negotiate the pact, but these deputations were all turned back by the Prussians who disclaimed any knowledge of Washburne’s action! Washburne had duped the Commune: all his efforts had been part of a plot to lull the Commune into inaction, while the enemy gathered its forces for the final onslaught on the workers’ government in Paris.

“The result of this American intervention (which produced a belief in the renewed neutrality of the Prussians, and their intention to intercede between the belligerents) was, at the most critical juncture, to paralyze the defence for two days,” according to the deposition of the Commune member. Full of confidence in Prussian neutrality, many Communards “fled to the Prussian lines, there to surrender as prisoners. It is known that this confidence was betrayed by the Prussians. Some of the fugitives were shot on sight by the sentries; those who were permitted to surrender by the Prussians were later turned over to the Versailles government.” (It is also known, however, that many Prussian soldiers deliberately disobeyed strict orders to shoot all Communards fleeing in their direction, and actually helped the latter to escape.)

“During the whole course of the Civil War,” the Communard’s statement continues, “Mr. Washburne, through his secretary, never tired of informing the Commune of his ardent sympathies, which only his diplomatic position prevented him from publicly manifesting, and of his decided reprobation of the Versailles government.”

The First International, in its letter to the American workers, notes:

“To appreciate fully Mr. Washburne’s conduct, the statements of Mr. Robert Reid and that of the member of the Paris Commune must be read as a whole, as part and counterpart of the same scheme. While Mr. Washburne declares to Mr. Reid that the Communals are ‘rebels’ who deserve their fate, he declares to the Commune his sympathies with its cause and his contempt for the Versailles Government. On the same 24th of May, while in the presence of Dr. Hossart and many Americans, informing Mr. Reid that not only the Communals but even their mere sympathizers were irrevocably doomed to death, he informed, through his secretary, the Commune that not only its members were to be saved, but every man in the Federal Army.”

The letter, signed by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels among others, calls upon the American section of the International to lay these facts before the working class, and to demand the withdrawal of the treacherous Washburne.

Another dark page in Mr. Washburne’s career as American ambassador is not recorded in the International’s protest letter. This concerns his energetic and unceasing attempts to force intervention against the Commune, not only by his own government–on the time-worn pretext that “attacks” on American property might be “anticipated”–but by others. He actually made at least one recorded attempt directly to invite the German troops (which, it will be remembered, were outside the gates of Paris, supposedly maintaining a strict neutrality) to invade Paris. On May 20th, he sent a message to Bismarck claiming that Communard troops had entered the American embassy and threatened to ransack it, and urging Bismarck to order his army to enter the city and crush the Commune. This provocative act of Washburne’s was entirely unjustified. His house had never been entered, as he himself explicitly admits in his Recollections (v. 2, p. 134). The Prussian government thereupon sent a peremptory note to the Commune threatening to enter the city if “satisfaction were not given within 24 hours,” but the incident was closed by the revolutionary government’s exposure of the baselessness of Washburne’s charges, and by the fact that Bismarck was still biding his time with the object of selling his services to his supposed enemy, Thiers, at the highest possible price.

Thus is again affirmed the truth of Marx’s statement in his masterpiece of historical literature The Civil War in France, completed within two days after the fall of the Commune: that when capitalism is confronted with a working class asserting its right to power “class rule is no longer able to disguise itself in a national uniform; the national governments are one as against the proletariat!”

NOTE

1. In his diplomatic dispatches and in articles written for Scribner’s, he not only repeated the usual canards directed against the Commune, but invented many of his own. Every one of these calumnies were later admitted to be false by the bourgeois press itself (when the Commune had been crushed and it no longer felt the hot breath of revolt on its neck). We haven’t the space to go into Washburne’s particular libels on the Commune; his every word on the subject breathes slander. In contrast, it is refreshing to turn to the realistic description of Paris under the Commune, written by a conservative vicar of the Church of England for the conservative Fraser’s Magazine in August, 1871, ending with these words: “And so my story ends. I’ve no horrors to tell you. I saw none…The Commune was a mistake; but it did keep Paris clean and morally wholesome; it did manage its police, its schools, its hospitals strangely well. This is to me the greatest marvel of all–the mixture of practical ability and wild dreaminess in the men who headed this grand confederacy…Let me be understood: I am not their apologist.”

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1935/v15n03-apr-16-1935-NM.pdf