A classic from Freeman who recounts his bohemian past with Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, and Robert Minor as an editor of the Liberator during the early 1920s in New York’s Greenwich Village. In the Socialist and later Communist Party since 1914, Marxist intellectual Joseph Freeman was a central figure in the literary Left as writer, critic, and along with the Liberator was a founder and editor of New Masses and Partisan Review.

‘Greenwich Village Types’ by Joseph Freeman from New Masses. Vol. 8 No. 9. May, 1933.

I came to Greenwich Village late in 1921 with a specific purpose. I wanted to know Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Robert Minor and the other editors of the Liberator. That magazine represented something I was seeking. I was then trying to coordinate an interest in poetry, burdened by years of training in the classic and romantic traditions, with an interest in the revolution, given intense and specific form by October. The Liberator was the organ of the one group in America in which art and revolution seemed to meet. The suppression of most leftwing publications during the war had made the Liberator one of the few sources where one could get authentic news about the Bolshevik revolution; the struggles in Germany, Hungary, Italy and Mexico; the revolutionary movement in the United States. At the same time it published fiction, poetry and drawings which were often revolutionary in content if not in form.

Now, in retrospect, we can all be wise; we can explain, with that clarity which comes long after the event, the Liberator’s shortcomings in developing a genuine revolutionary art and literature. Yet the fact remains that in its time this publication performed a unique historic task. It gathered together and developed such revolutionary writers and artists as the prevailing conditions made possible.

Chiefly the Liberator expressed the “revolt” of certain types of intellectuals against bourgeois convention. The “revolt” was, on the whole, individualistic. Against the pressure of business ideals in work and puritan standards in personal conduct, sensitive individuals, mostly from the middle classes, demanded the right to pursue art, to experiment sexually, and to absorb political ideas which came to them partly from books, and partly from such influence as the revolutionary movement exercised on its literary fellow travellers.

Such “free” spirits congregated in Greenwich Village, where rent was cheap and the bohemian tradition glittered. As an editor of the Liberator and later of the New Masses, since 1922, I have had occasion to meet most of these “free” spirits at one time or another. No two of them were alike. The majority, it may be said, came to bohemia because it was a border country stretching between two worlds. It combined a post-graduate school, a playground and a clinic for those who had broken with an old culture and had not yet found a new one, or had not yet discovered and accepted the fact that they were irrevocably committed to the old.

I speak of this bohemia in the past tense because the Village I knew is dead. If another has arisen in its place I do not know it. The old one affected American literature and art. Its history is worth writing; and when I had finished reading the introduction to Albert Parry’s Garrets and Pretenders I thought he had done it. This introduction speaks of the Marxian writers as the “only ones to approach and discuss Bohemianism not in a vaguely sentimental or grossly abusive way but more or less dispassionately, almost scientifically.” The author attempts to formulate the Marxian viewpoint on bohemianism; he cites Marxian writers on the subject. From this I was led to expect if not a Marxian interpretation of bohemia at least an attempt to explain its social role in some plausible terms. I was disappointed. There are over three hundred pages of names, episodes, gossip, quotations, many of them entertaining; but hardly anything which shows the serious side of the Village.

And the Village did indeed have a serious side. It may be said that this serious side was its essence. The fact that its inhabitants drank, made love, wrote poems, stayed up late at parties and occasionally committed suicide is unimportant unless it is related to what these people were seeking.

Their quest now seems to us trivial. We live in a period of great historic events; we see an entire civilization falling to pieces, and another rising to take its place. The violent struggle of social classes, the breakdown of the economic structure of capitalism, the drilling of armies for a new war make the glamors and despairs of bohemia seem infantile. Yet a good history of the Village would show that its “wild” and “free” life was not unconnected with the disintegration of capitalist society.

“The generation to which Waldo Frank and I belong,” Floyd Dell wrote in 1920, “is a peculiar and unhappy generation, and I don’t wonder that the older generation looks at it askance. It is a generation of individuals who throughout the long years of their youth felt themselves in solitary conflict with a hostile environment. There was a boy in Chicago, and a boy in Oshkosh, and a boy in Steubenville, Indiana, and so on—one here and there, and all very lonely and unhappy…They were idealists and lovers of beauty and aspirants toward freedom; and it seemed to them that the whole world was in a gigantic conspiracy to thwart ideals and trample beauty under foot and make life merely a kind of life-imprisonment. So it was that these youths came to hate and despise the kindly and excellent people who happened to be their elders, and who were merely hard at work at the necessary task of exploiting the vast raw continent which Christopher Columbus had not very long before discovered. This generation had to make, painfully enough, two important discoveries. It has had, in the first place, to discover its own corporate existence, to merge its individual existences together, and get the confidence and courage that can come only from the sense of mass thought and mass action. But the trouble is that each one of us, in our loneliness, has become a little odd, a little peculiar, and more than a little suspicious…Individualism is the very fabric of our lives, we who have brooded too long apart to become without pain a part of the social group to which we belong.”

Brooding and oddities lead to poses, to that theatricalism and pretence which Mr. Parry implies in his title and examples of which crowd his work. But pretense itself requires explanation. The declassed intellectual, uprooted from his original social environment and not yet rooted in a new one, suffers from acute internal discord. Until that discord is resolved in terms of reality, he attempts to resolve it in symbols. He pretends to be what he hopes to become, or at least that which will protect him from what he fears to become.

What he most fears in the early stages of his bohemian existence is a return to the bourgeois world from which he has just fled. That return has been the fate of most Bohemian. For the Villagers of the twenties, however, it did not entail any special hardships. The “compromise” had its agreeable side. They were no longer odd, peculiar or unhappy. The bourgeois world over took and surpassed them; it absorbed their talents and expropriated their poses. Bohemian pretences were transferred from the garret to the suburban home or the Gramercy Park studio. During the boom period ending in the debacle of 1929, the prosperous middle classes went bohemian on a large scale. The speakeasy lifted to a “higher level” the drinking, the sexual experiments and the wit of the Pirates Den. The manners and morals of the Village became the morals and manners of sections of the middle and even the upper classes. Expanding business converted the “vagabond” poets of the Village into editors, ad writers, publicity agents, columnists, and novelists; the “vagabond” artists into magazine illustrators, commercial designers, portrait painters, and department store decorators. And these ex-bohemians, through the medium of the press and the movies, brought to the middle classes some of the “free” thought and “free” conduct of the Village. A balance was struck. The prosperous middle classes needed a little bohemianism to spend their money in ways not sanctioned by the puritan tradition; the bohemians needed a little puritanism to go with their newly acquired money.

Today the economic crisis has once more declassed a large part of the intelligentsia. But this time they have not gone bohemian. Bohemianism requires a certain amount of social stability. The bohemian wishes to “shock” the bourgeois. For this purpose the bourgeois must be well entrenched, secure; and the bohemian himself must feel that the road back to the world he is “shocking” is not entirely closed. In the depths of his heart he not only fears but hopes that his eccentricities, which he usually considers a sign of genius, will earn him a fatted calf as the returning prodigal son. It is not capitalism he hates, but the responsibilities which any highly developed social system imposes upon its members. The bohemian who finally accepts law and order in life may graduate to communism if he realizes that it represents a higher law, a superior order; but the bohemian who has no objection to capitalist law and order—provided he is to some extent exempted from their burdens—gladly returns to the fold.

The bohemian intellectuals who matured during the war considered themselves lonely and unhappy lovers of beauty and aspirants toward freedom. Toward the end of the Coolidge era, when most of them had been absorbed into bourgeois society, a more realistic note crept into their self analysis.

“After a brief enthusiasm,” a well known authority on the American intelligentsia wrote in 1926, “the intelligentsia has for the most part become indifferent to the new order in Russia—an indifference which marks a secret temperamental antipathy…The reason for such an antipathy lies in the fact that the Bolsheviks are actually imposing order upon chaos—an order all too much resembling, in its governmental and industrial paraphenalia, and its rigorous concepts of ‘duty’, that order against which the intelligentsia is still in hopeless rebellion at home. The introduction of machinery into Russia, and eventually throughout Asia, is not the sort of change to warm our hearts…Far from it. The American intelligentsia has a deep sentimental attachment to barbarism and savagery, preferably of a nomadic sort.”

These words accurately reflect the temper if not the existence of the American intelligentsia during the boom period. Pessimism and despair was assuaged by a romantic flight from reality. In the minds of many intellectuals the violent reaction against the war became transformed into a general reaction against “civilization.” They were disillusioned about liberalism, pacifism, reform and other dreams from which the war had so rudely awakened them. Planning and acting seemed futile. The world was in a hopeless chaos. Anything done to change it was so much wasted effort. In the Twenties the “tired radicals” were never tired of explaining the futility of political struggle.

Despair in politics was accompanied by primitivism in art and literature. Main Street and Babbitt sneered at mechanization and standardization; Emperor Jones took the intellectual, at least imaginatively, into the jungle; Anna Christie, to sea; The Wasteland, up to the austere rocks of philosophic hopelessness; The Bridge of San Luis Rey, along a pseudo-classical highway to a Peru that never was on land or sea. Branch Cabell manufactured a tinsel world, and the revival of Herman Melville and the white whale restored a dead one. The dark and bitter poetry of Robinson Jeffers attracted the attention of the intelligentsia, and the cynical American Mercury assumed the leadership of an era which, intellectually, spat its beer out upon civilization as a whole. Literary critics discovered that romantic love was dead and all human values corrupted. The intelligentsia which formerly admired Dewey now hailed Spengler. By and large it took little interest in the tremendous social revolution going on in Russia. Few intelligent books were published on the subject; practically none were translated from the Russian; the works of Lenin were unknown; no theatre produced Soviet plays until the end of the decade, and important Soviet films were not shown until 1926. Most of the handful of intellectuals who did go to Russia in the twenties were interested less in the revolution than in those primitive and “picturesque” relics of Czarist days which the revolution was busy destroying.

But things are different now. Never has the American intelligentsia been as interested in Russia as it is today. This includes not merely Greenwich Village poets but engineers, doctors, lawyers, teachers, newspapermen and students. Many intellectuals with and without a bohemian background, are not only sympathetic toward the Soviet Union but support the communist movement in this country as well.

The American intellectual is no longer alarmed by the spread of machinery to Russia and Asia. He does not understand the fear and ignorance of machine civilization which marked the Village a decade ago. He goes to movies of Dnieprostroy where the bohemian used to see Georgia O’Keefe’s freudian vegetation. He writes indignant or apologetic articles for the American press when he finds a room in Moscow with candles instead of electric lights, with a bathtub lacking hot water, and a toilet that doesn’t flush; in short, a room which resembles the bohemian “studio.” It is only in the realm of the imagination that the intellectual has a deep sentimental attachment to “barbarism and savagery, preferably of a nomadic sort.” In daily life, doctors, lawyers, and professors gladly avail themselves of that machinery which in imagination they profess to dislike. Even most bohemians I have met do not rebel too strenuously against suburban homes with “all modern improvements,” a radio, a roadster, and a little garden. Their “nomadic” urges are easily satisfied by occasional trips from Westport to New York or vice versa. In the Village, the bohemian’s “nomadic” existence consists of sleeping in a different house every other night, or, as one writer wittily phrased it, “flitting from breakfast to breakfast.” This is a hard life. Eventually it engenders a frantic longing for a home of one’s own. When the bohemian acquires such a home he is “nomad” and “vagabond” in fantasy only. He spends the rest of his life in his little Cherry Orchard, never venturing to the metropolis of his dreams.

I mention these matters not to rebuke the bohemians for succumbing to love of comfort. Nothing is more natural. For the most part, bohemians have the good grace not to pretend that they are either heroes or ascetics. On the contrary. Bohemianism is essentially the cult of the sybaritic life. Its problem is to enjoy the aristocrat’s leisure and irresponsibility on a pauper’s income. Was it not the brightest star in the bohemian firmament who wrote in 1918 that “life is older than liberty; it is greater than revolution; it burns in both camps?” Life, added this poet who was brilliantly defending the October Revolution, “is what I love”; life for all men and women, of course, but “first for myself.” That “life” which is “greater than revolution” includes comforts. In the Village the bohemian receives them as a guest; when he graduates to the suburb he dispenses them as a host. In itself that is no crime. But the attitudes of the Village may be carried over to the suburb, and the bohemian state of mind may persist long after the bohemian life has ceased.

The bohemian hates order. As a confused adolescent or frustrated adult he escapes to the Village because he finds the bourgeois order intolerable. But as a rule it is not the economic and political bases of the capitalist order which repel him. In most cases he does not understand them. What makes him feel that life is “a kind of life imprisonment” are the fantastic demands of religious superstition, the rigors of uncomprehending parental authority, the chains of antiquated sexual mores. When these burdens press heavily upon him he begins to generalize; he becomes a literary anarchist; he loathes not merely the specific results of the capitalist order but all order; he cannot distinguish between law and capitalist law, just as the Luddites could not distinguish between machinery and the capitalist use of machinery.

In this way the bohemian revolts against certain concepts of capitalist society which in varying forms belong to all organized society and which are carried to a higher level in socialist society. They are the well-known virtues: “such dull matters as honesty, sobriety, responsibility and even a sense of duty.”

Bohemia is the realm where one can—for a time, at least—dodge these demands of organized society. When they can no longer be evaded, the bohemian who is not absorbed in the revolutionary movement returns to the bourgeois world. Life presents him with the alternative: comfort in the bourgeois order or struggle for the socialist order. To the average bohemian, saturated with middle class illusions, order is order, whether it is capitalist or socialist. The choice, then, is clear. If—as one writer phrased it—the intellectual has “to make himself over into what is to almost all intents and purposes a good American businessman, he would prefer to enjoy all the American businessman’s rewards.” That is why so many bohemians went back to the bourgeois world during the boom period. At a time when individuals may shift from class to class, bohemia is extremely fluid. A clerk may become a businessman; a bohemian writer for radical magazines may become publicity man for a big corporation. Both rode the bull market. The prodigal son, returning from the Village, did not receive “all” the American businessman’s rewards, but he got enough crumbs to bring some comfort and stability into his life.

Right there is the rub. The economic crash came. American business is no longer able to give handsome “rewards” to intellectuals. Thousands of them have been thrown out of work and expropriated of their Fords and radios. Thousands of new ones have not had a single job since leaving college. Some of them have begun to realize that it is not a choice between order and lack of order, in the abstract, but between capitalist order which is disintegrating and socialist order which is developing. And many of them who have never had a bohemian tradition or have outgrown it know that the order in Soviet Russia resembles the capitalist order only in certain superficial aspects; they realize that in essence it is a new order—an order which for the first time makes eventually possible that freedom to which the intellectual aspires.

The evolution of the bohemian intellectual is no easy matter to describe. Its history ought to be more than a collection of anecdotes. It ought to be a key to sections of our contemporary intelligentsia, to those who have not yet thrown off their bohemian heritage. It might aid some of them in getting rid of this burden by revealing the origin of illusions which they continue to mistake for realities. It would also bring out the creative side of the Village which made it possible for some writers and artists to go beyond bohemianism. And—quite incidentally, of course—it would explain why the New Masses cannot follow Albert Parry’s advice to recapture the “romantic moods” of the old Masses. The period in which we live requires not so much romanticism of mood as firmness of purpose and clarity of thought.

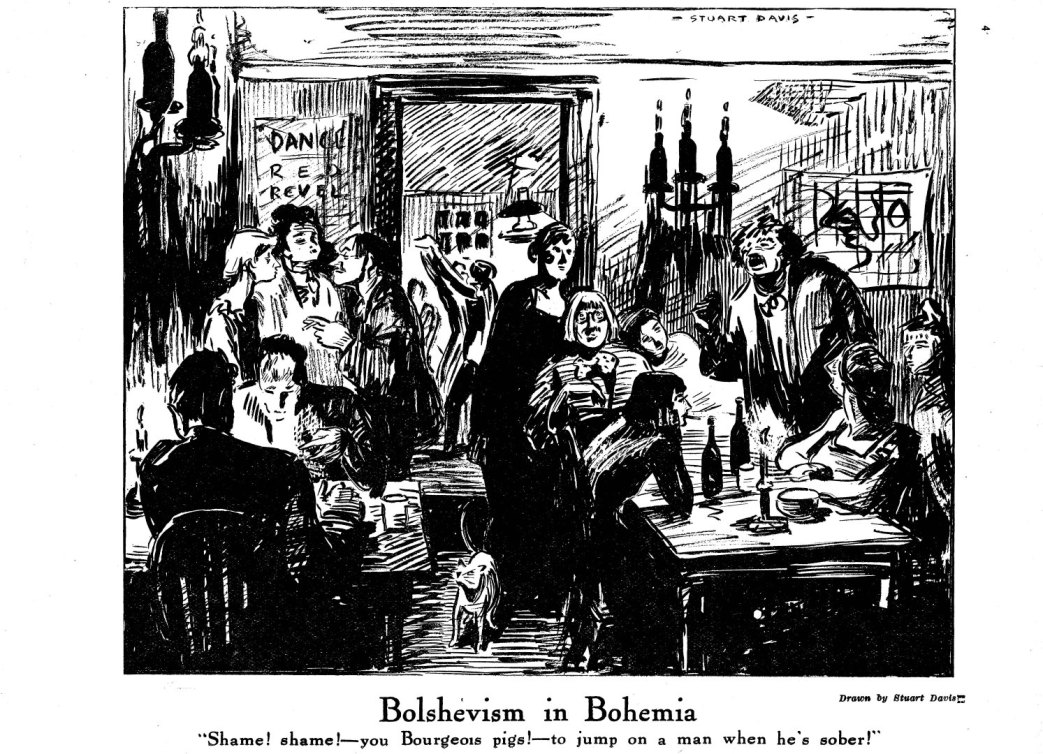

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1933/v08n09-may-1933-New-Masses.pdf