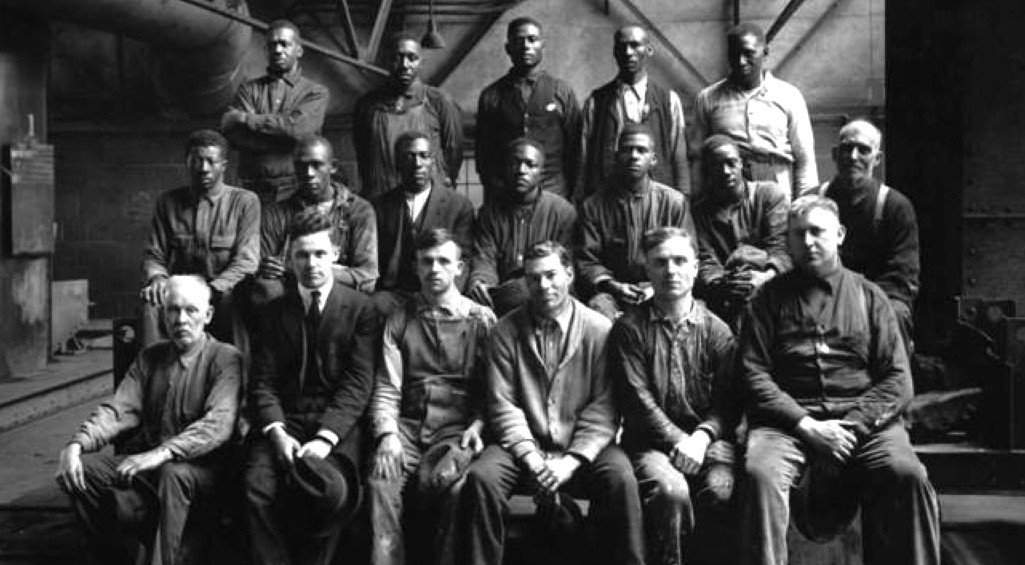

Philadelphia, home to one of the oldest and most important Black urban centers in the U.S., had–and has–particular characteristics as well as those it shares with other ‘Border Cities’ such as Baltimore, Cincinnati, St. Louis, and Kansas City. Organizer Thomas Dabney looks at unions among Philadelphia Black working class.

‘Philadelphia and the Negro Worker’ by Thomas L. Dabney from Labor Age. Vol. 16 No. 7. July, 1927.

Bringing The Message to The Negro In The Cradle of Liberty

Philadelphia is a notorious open shop city. Both culturally and politically it has fallen far below the level it once held in American history and trade unionism. Having become the center of American democracy (what little we had) in 1776 and the Labor movement in 1827, Philadelphia has in recent years degenerated into the stronghold of conservatism and incompetence in politics and indifference and decadence in trade unionism. Consequently, organizing efforts among all workers are most difficult and unpromising.

So far as organizing work is concerned, Philadelphia is suffering from three general unfavorable conditions: poor industrial conditions, unsatisfactory race relations among the workers, and poor working class leadership.

Because the industrial situation is poor there is keen competition among all workers; and as is the general rule this competition tends to head up in group competition along racial lines. Unionizing efforts are made more difficult by the open shop movement sponsored by the employers. The disorganized Negro workers and white workers and, in some cases, the organized white workers and the disorganized Negro workers have opposed each other, the latter playing the role of scabs. On the other hand, white workers have deliberately fostered scabbing among Negro workers by resorting to every trick conceivable to keep Negroes out of the unions and out of certain jobs which they covet for themselves. There are cases where white trade unionists have done everything in their power to oust their Negro brothers from jobs which they wished to preserve for their white brothers!

The War—and After

In Philadelphia, as elsewhere in America, it has been the policy of white workers—particularly those in the unions—to keep Negro workers out of the best paying and skilled trades. White trade unionists have always feared the competition of Negro workers, and they have zealously guarded their privileged position. When the war came, however, conditions were changed, and Philadelphia Negroes secured jobs which only white workers could get before the war. As a result of the war, organizers had a wonderful success in building up trade unions. Negro workers were not only accepted in the unions, but they were urged to join.

Following the war production fell off rapidly, the volume of business decreased, and unemployment ensued. These conditions had a tremendous effect upon race relations in the trade unions and among the workers of both races generally. As there were not enough jobs for trade union members, justice in the matter of placing union members on jobs was often left to the discretion and honesty of trade union officials. In unions with a mixed membership discrimination against Negro members was almost invariably the rule. The writer secured some information on this point from a reliable source regarding the experience of some of the Negro members of one of the carpenters’ locals of Philadelphia. At this particular local white and Negro carpenters used to gather day after day in the hope of getting jobs. Three, four and five white carpenters were sent out on jobs daily, but practically no Negro carpenters got work. From the viewpoint of membership in this local every ten carpenters sent out on jobs should have included one Negro carpenter. The policy of the local, however, was that of placing all of the white carpenters first, if possible, and giving Negro carpenters jobs ‘if any were left. Naturally, such a selfish policy engendered suspicion and distrust among the Negro carpenters.

Anything to Get Jobs

In a certain degree this policy was followed by all unions in Philadelphia with a mixed membership, following the war. Among disorganized workers this attitude took the form of general opposition on the part of white workers against Negro workers. By 1922 Negro workers were forced to follow any policy which would land them jobs. In some cases it was through scabbing, in others by concerted efforts to get into the unions, and lastly by organizing separate Negro unions or locals. In most cases, however, Negro workers promoted their group interests by taking the part of employers. A classical example of this is the incident connected with the construction of the Fox Theatre in 1923. The contractors were rushing the job through so that the scheduled grand opening would not be delayed, when a strike of the dissatisfied white plasterers threatened to hold up the work. The contractors, anxious to finish the job on scheduled time and unwilling to accede to the wage demands of the striking plasters, went in search for Negro plasterers. Negro plasterers were secured, and they completed the job within the stipulated time. Since that year these contractors have continued to employ some Negro plasterers in addition to white plasterers.

It would be misleading, however, to play up the racial factor as the most fundamental one against successful organizing work among Philadelphia Negro workers. At bottom the poor success of trade unionism among Negro workers in Philadelphia is due to poor industrial conditions. The bosses have the upper hand and they are determined to keep it. Employment is abnormal; business is rotten and competition among the workers is keen and relentless. The morale of the workers is low, hence they are inclined to let conditions remain just as they are. In addition to the general apathy among the workers, many trade union leaders seem to be apathetic and indifferent.

So far as Negro leaders are concerned I do not know one here in Philadelphia who is genuinely interested in the problems of Negro workers. If they know little about trade unionism, they care less. Every effort started in behalf of Negro workers is regarded by many so-called Negro leaders as a bid to Negro workers to embrace communism. Like Calvin Coolidge they lie awake at night finding haunts of the possible spread of red propaganda among the American workers.

Leadership of Own Choosing

Negro workers in Philadelphia are in a rather peculiar situation. With no real leaders among the old line trade unionists, no sympathetic and intelligent leaders in their race, and no competent, militant, and organized comrades among the white workers, Negro workers can rely upon only one hope—the hope of developing among themselves a courageous and intelligent leadership of their own choosing. These leaders will have to build up a strong economic organization to foster unionism among Negro workers, unless Negro workers are satisfied to await the slow development of industrial conditions to the point where the general economic situation will be in their favor as a racial group. Such a procrastinating policy, however, is undesirable. The organizing of the workers and the cooperation of Negro workers with white workers should be consciously and systematically done. Blind and forced action is too costly; it leaves in operation old, narrow, and prejudiced ideas of race and class that militate against real and healthy cooperation between Negro and white workers.

Negro workers of Philadelphia cannot afford to wait for a change of attitude on the part of their white fellow workers. If white workers were class conscious and trade union to the core, they would not be imbued with race hatred and color prejudice as they are. While the situation is so unsatisfactory as regards Negro leaders and white trade union leaders, it is encouraging to note the gradual rise of leaders among the most militant groups of Negro workers in Philadelphia. Brother William N. Jones, financial secretary of Local 1116 of the International Longshoremen’s Association, possesses the real qualities of a working class leader. The organizing of Local 1116 was no easy task. Through hard work and determined effort Brother Jones, with the help of the most militant longshoremen, succeeded in reorganizing the local last December. This local has a membership of 2,500, or about 90 per cent of all the longshoremen excepting the 3,000 employed in the coastwise trade. The Negro members of Local 1116 comprise about 90 per cent of the total membership. Plans are in operation to organize the coast–wise men.

Ladies Garment Workers’ Good Work

Another instance of the development of leadership among the working class of Philadelphia is that of the work of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union. Fortunately, the garment workers were successful in securing a colored organizer who is particularly qualified to do this work. Mrs. Emma Thompson is proving herself a real leader of the Negro garment workers. When one remembers that about 1,000 colored women are now employed in the garment industry in Philadelphia, one can readily see the need and value of a good colored organizer and leader for these colored women workers. Mrs. Thompson is just the sort of leader that is needed for this work. The organizing of the colored garment workers came about as a byproduct of a threatened strike of the garment workers last winter. When the situation between the I.L.G.W.U. and the bosses was about to precipitate a strike, attention was soon focussed on the colored women as possible strike-breakers. The I.L.G.W.U., with the cooperation of Mr. Forrester B. Washington, executive secretary of the Armstrong Association, began a campaign to organize the colored garment workers. A Citizens’ Committee, organized by Mr. Washington, gave the campaign its moral support. As a result of this campaign, a great many of the colored workers were organized and the strike averted. Most of the credit for this work is due to Mr. Washington of the Armstrong Association of Philadelphia and Mrs. Emma Thompson of the I.L.G.W.U.

There are other examples in Philadelphia which show the tendency of Negro workers to develop their own. leaders. The Public Waiters’ Association, organized in 1903, has a membership of 150. Although this Association has done little to organize all the men, it has been of great economic and financial aid to its members. There is also a colored local of carpenters officered by Negroes. This local has only 150 members. The cement finishers’ local has 200 colored members; and its business agent is colored. Some of the Negro unions of Philadelphia are merely associations with a small and well-nigh insignificant membership. They have never been well organized and do not contain a large enough per cent of the men of their trade to give them authority to act for the workers of the trade. This is one of the handicaps of the Red Caps and Railroad Employees’ Association, organized in 1921. This Association, headed by Mr. Cornelius Thompson, has a membership of 125, less than one-third of all the red caps and cleaners in Philadelphia. The Association hopes, nevertheless, to organize the workers, especially the red caps, throughout the country when conditions are more favorable for such work.

The time is fast approaching in Philadelphia when Negro workers and white workers must disregard the old, foolish notions of race and color held by their ignorant parents. The greedy bosses are organized; the workers are unorganized. The bosses are realists; they are after profits and they will use either race against the other to make money. The workers are sentimentalists; they fight each other and worship that etherial, superficial thing called race. It is time for the workers of Philadelphia to face realities. Negro workers are gradually being converted to trade unionism, and they will begin more and more to throw in their lot with the Labor movement. But in this movement they need the good wishes and the cooperation of the white workers. Will the white workers give their moral and financial support toward the organizing of their fellow workers?

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v16n07-jul-1927-LA.pdf