Amidst the wreckage of post-war Germany, an effervescence of radical arts–with a focus on the playwright Ernst Toller.

‘Art in Starving Germany’ by William Schack from The Liberator. Vol. 5 No. 10. October, 1922.

THOSE of us who are at bottom idealists and whom this disturbing generation has solidified into cynics may well look to the Germany of today for consolation, for nowhere in the world is the economic disintegration so richly compensated for with spiritual produce. True, there are countries that have fallen to a lower economic level, but for practical calculations Germany is rapidly approaching that level. Even now the average working man cannot supply his family with any butter or fruit or a decent amount of vegetables or meat. The purchasing of clothes is a holiday–a holiday such as a funeral affords. I saw a young fellow accompanied by four friends spend an hour and a half in a shop selecting a low-priced suit; it was indeed an earnest conference.

For the poor it is a sacrifice to buy the cheapest seats at the opera or the theatre, even in the smaller cities; and everybody knows that the German scale of prices is much lower than our own. The rich can of course afford the better places and they bring their sandwiches with them! Foreigners of moderate means ride in taxis and cabs while the average native thinks twice before he takes a trolley. One rainy day when I was tired and in a hurry I asked the janitor where I could get a ‘bus. “Oh, what do you want to ride for?” he said in the gravest of voices. “It isn’t very far, and it’ll cost you a pile of money.” The “Menge Geld” he referred to was four marks, or in American money about three-quarters of a cent at that time.

The foreign invasion not only consumes the best that the country has to offer in a material way. Much worse is its undermining of the general morale. The process has not gone very far as yet, not as far, surely, as in France, whose temperament is more fluid, but it is setting in determinedly. The natives of Coblenz may feel grateful to the American soldiers who give their children plenty of candy, but how do they feel when they see tremendous barracks being built and not a single civilian dwelling, which are so badly needed? Or in normal times would that landlady in Mainz have asked me in so foul a tone, “Ist die Dame Ihre Frau?” Compared to this, the fact that luxurious Wiesbaden has been taken over chiefly by foreigners is of minor significance.

Half-starved and gnawed by an envy which it would be intolerant not to forgive, have they given up the fight? The first thing you see when you get out of the station at Wiesbaden is, not a garish sign telling you and the world that YEABO is the best cigarette in the world, or even posters to divert you to one resort or another, but a modest announcement with a directing arrow to the current exhibition of art. Yes, and this city of rheumatics and rotters has just built a costly and beautiful museum. At the Dresden station you also find announcements of art and porcelain exhibitions, while Dusseldorf has more pictures in it than New York.

If you approach Dusseldorf from the Rhine, you will come first to the Kunst Palast, situated in what must be the simplest and most beautiful green in the world. It is a magnificent building and holds at present a vast collection of contemporary German painting and drawing, varying in mood from still life to factory realism and in technique from the classic to the most wildly futuristic. To add to your bewilderment and interest, you will find a whole roomful of modern work on the subject of Christ–portraits, descents from the Cross, and so on. If you have any energy left after that, you can visit the Academy of Art, where there is a considerable collection of old masters. A few minutes away you have the Kunsthalle, with a standing exhibit upstairs and contemporary work on the lower floor. A day’s rest, and you will be ready for the first international exhibition, which (until the middle of July) occupied the upper floor of the largest department store–Tietz. Here you will find mostly intransigents, who would have nothing to do with the reactionaries of the Kunst Palast, with their mere realism. You will find the November Gruppe, the Secessionists, and others of the Left wing; and you can learn what the younger artists are doing all over the world. All this in a city of less than half a million population.

The theatre does not lag behind. Even in these late July days one can see at least two plays of value in Berlin. New Yorkers will soon have a chance to judge for themselves Die Wunderlichen Geschichten des Kappelmeisters Kreislers. Familiar as the method of retrospective narrative is, and though the story is essentially sentimental, this play is nevertheless remarkable for the restraint and concentration with which it is presented and for its marvelously efficient staging. I believe New York has never seen a play given in forty-two scenes. Only once is the full stage utilized; the other scenes, simplified to the semi-obscurity of Rembrandt paintings, occupy a small part of the stage–speaking cubically, for there are sets representing a box in a theatre and rooms on an upper floor.

The story moves swiftly from scene to scene, with the narrator and his listener coming in now and again, practically without intermission. Here is an efficiency that does not render economy ugly; a fine symbol, at the same time, of what our industrial era could accomplish if its extravagant means could be utilized for life-enhancing ends. If there is nothing essentially new in the play, it is at least a union of the ages, for after all the multiplicity of scenes is Shakespearian and its concentration is that of the modern novel, its swift movement that of Eugene O’Neill. The New York producer must have courage, for I doubt that the average theatre-goer will enjoy the fine realistic strain that runs through the play despite its sentimentality, and he may even be disconcerted by a musical accompaniment that is far beyond the banalities that such music usually consists of. Another play of far greater significance for the theatre, and one which America will probably not see for a long time, is Ernst Toller’s Die Maschinensturmer, which is a story of the Lud uprising in England at the beginning of the present industrial era. Before and during the war, Toller’s plays were barred from the stage, and now that one of his best works is achieving a well-merited success, he himself is serving the third year of a five year prison sentence for having led a Communist uprising in Bavaria.

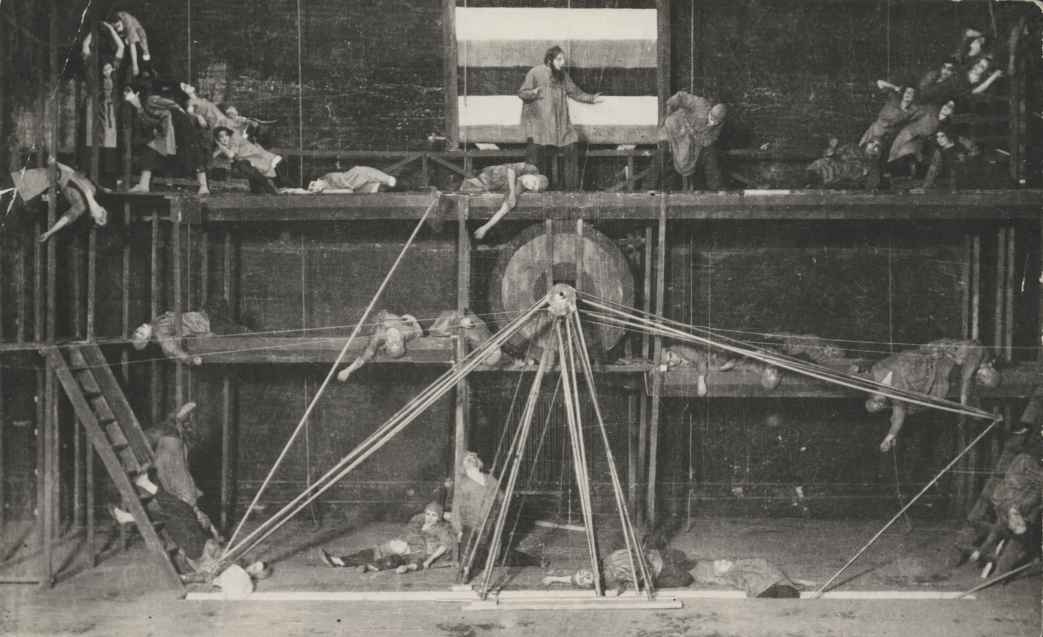

In The Machine Wreckers, individuals do not emerge; they all play the parts laid down for them by economic forces. One must not infer, however, that it is therefore an exercise in Marxism, as Bernard Shaw’s plays are algebra exercises appended to his prefaces. It does not attempt to portray people in the fullness of their lives, but only as they react at a certain crisis, in this case at the introduction of a contraption which threatens to starve out the great majority and to destroy those who for the moment earn their living by it. When The Mob was produced at the Neighborhood Playhouse, we felt that the mob scenes were admirably handled. What should one say here, where the mob contains three times as many people and where there is no concerted growling and action, but a sensitively distributed response among the individuals of the crowd which finally fire and break into flame by spontaneous combustion?

Certain elements of the play terrify one by their starkness. “Would you like to play?” a group of ragged children are asked. “Play? What does that mean.” “Shall I tell you a fairy tale?” “Fairy tale? What is that?” They listen a few moments without pleasure, without understanding, and suddenly break away from the narrator and start a rough and tumble fight. Also Arbeiterslied, sung at intervals like a dead march, chills the blood with its prelude of desolation, and even its final note of revolt has a dank tone of hopelessness.

If we could gather the human material to produce such a play, we should still be without a stage, for Die Maschinensturmer is playing at the former Circus, with the usual though lower stage and a long arena leading up to it which serves for the coming and going of the mobs. One gets a forceful idea of the significance of this play for the future when one sits close to the arena, for one feels what an earnest mob can do and one feels that the future holds such mobs in store for us. It is not such a play as Upton Sinclair might write, for it does not flatter the common man. It merely shows that he is human and that he is all too prone to crucify those who would save him, for in the end the mob kills the man who gave up his mother and brother and wealth to lead the strikers. Toller handles his intellectual elements with a sure balance, without which no good work can result from such a subject.

It is certain that the former dynasties which governed Germany were evil in that they handed down law, even though good law, from above. Whether we paid too high a price for their removal nobody can yet tell. One other thing is certain, and that is that in this country, suffering heaviest for the sins of its rulers as it is, civilization is making its most concentrated effort to endure.

Cologne, July, 1922.

The Liberator was published monthly from 1918, first established by Max Eastman and his sister Crystal Eastman continuing The Masses which was shut down by the US Government during World War One. Like The Masses, The Liberator contained some of the best radical journalism of its, or any, day. It combined political coverage with the arts, culture, and a commitment to revolutionary politics ay a pivotal time in Left history. The writings by John Reed from and about the Russian Revolution were hugely influential in popularizing and explaining that events to U.S. workers and activists. Increasingly, The Liberator oriented to the Communist movement and by late 1922 was a de facto publication of the Party and was sold to the Party by Eastman. In 1924, The Liberator merged with Labor Herald and Soviet Russia Pictorial into Workers Monthly. The Liberator is an essential magazine of the US left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1922/10/v5n10-w55-oct-1922-liberator-hr.pdf